Phd Thesis Wouter Veenendaal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repubblica Di San Marino

http://www.consigliograndeegenerale.sm/new/proposte_di_legge/vis_lavo...posta=6870&colonnakey=idlegge&tabella=leggi&colonna=testDISCLAIMER: As Member States provide national legislations, hyperlinks and explanatory notes (if any), UNESCO does not guarantee their accuracy, nor their up-datingolegge&testo= on this web site, and is not liable for any incorrect information. COPYRIGHT: All rights reserved.This information may be used only for research, educational, legal and non- commercial purposes, with acknowledgement of UNESCO Cultural Heritage Laws Database as the source (© UNESCO). LEGGE 28 ottobre 2005 n.147 REPUBBLICA DI SAN MARINO Elenco dei manufatti o immobili con valore di monumento di cui al Capo VII, Sezione I della Legge 19 luglio 1995 n.87 (Testo Unico delle Leggi Urbanistiche ed Edilizie) Noi Capitani Reggenti la Serenissima Repubblica di San Marino Promulghiamo e mandiamo a pubblicare la seguente legge approvata dal Consiglio Grande e Generale nella seduta del 28 ottobre 2005. Art.1 (Valore di monumento) Il valore di monumento è attribuito ad un manufatto o immobile in base a quanto disposto dall'articolo 1 della Legge 10 giugno 1919 n.17 e dall'articolo 197 capo VII sezione I della Legge 19 luglio 1995 n. 87. Fanno parte dell'elenco dei manufatti o immobili con valore di monumento i manufatti o immobili di interesse archeologico e paletnologico ed i manufatti o immobili di interesse storico ed artistico nonchè culturale ed ambientale la cui costruzione risalga ad almeno cinquant'anni o che comunque siano attribuiti ad autore non vivente. Art.2 (Dell’elenco) L'elenco, redatto sulla base delle indicazioni e delle valutazioni fornite dalla Commissione per la Conservazione dei Monumenti e degli Oggetti d'Antichità ed Arte (CCM), contiene manufatti o immobili con valore di monumento individuati mediante documentata catalogazione di cui all'allegato A della presente legge. -

History of San Marino

History of San Marino The official date of the foundation of the Republic of San Marino is AD 3 September 301. Legend states that a Christian stonecutter named Marinus escaped persecution from the Roman emperor Diocletian by sailing from the Croatian island of Arbe across the Adriatic Sea to Rimini. Marinus became a hermit, taking up residency on Monte Titano, where he built up a Christian community. He was later canonized andthe land renamed in his honor. Throughout the Middle Ages, the tiny territory made alliances and struggled to remain intact as a string of feudal lords attempted to conquer it in their attempts to control the Papal States. On 27 June 1463, Pope Pio II gave San Marino the castles of Serravalle, Fiorentino, and Montegiardino. The castle Faetano voluntarily joined later that year, increasing San Marino’s boundaries to their present size. In 1503, Cesare Borgia managed to conquer and rule San Marino for six months. In 1739, Cardinal Alberoni’s troops occupied San Marino. After many protests, the Pope sent Monsignor Enrico Enriquez to investigate the legality of Alberoni’s occupation, and San Marino subsequently regained its independence on St. Agatha’s day, now a national holiday. In 1797, Napoleon invaded the Italian peninsula. Reaching Rimini, he stopped short of San Marino, praising it as a model of republican liberty. San Marino declined his offer to extend its lands to the Adriatic Sea. With the fall of Napoleon, San Marino was recognized as an independent state, adopting the motto Nemini Teneri (Not dependent upon anyone). San Marino remains neutral in wartime, but many Sammarinese volunteered in the Italian Army during World War I. -

Gordon, Robert C. F

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR ROBERT C. F. GORDON Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: January 25, 1989 Copyright 1998 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background ducation arly career Baghdad 1956-1959 Baghdad Pact Organi%ation Political situation Coup Attacks on American embassy (hartoum 1959-1961 Military government Ambassador Moose Political situation Tan%ania 1964-1965 Ambassador ,illiam -eonhard Persona Non /rata President Nyerere 0ome assignment Personnel 1912-1920 Dealing with complaints Selection process ,illiam Macomber Handicapped facilities Florence 1912-1912 6.S. interests in Florence Dealing with local communist governments ye disease 1 Mauritius 1920-1928 6.S. interests in Mauritius Political situation conomic situation Conclusion Achievements Foreign Service as a career INTERVIEW Q: Mr. Ambassador, how did you become attracted to foreign affairs) /O0DO.9 ,ell, I was born and raised in a very small town in Southwest Colorado. And my father had been in the Spanish-American ,ar and had left and come back through Mexico where he stopped off and worked in the American mbassy in Mexico City for awhile on his way back to the States. And he used to talk about it. I loved travel books, and maps, and so forth. As a result, when I went to college, instead of going to the 6niversity of Colorado, I went to the 6niversity of California at Berkeley because it had a major in international relations. So I sort of had this idea in the back of my head, not knowing really what it was, since high school days. -

The United Nations' Political Aversion to the European Microstates

UN-WELCOME: The United Nations’ Political Aversion to the European Microstates -- A Thesis -- Submitted to the University of Michigan, in partial fulfillment for the degree of HONORS BACHELOR OF ARTS Department Of Political Science Stephen R. Snyder MARCH 2010 “Elephants… hate the mouse worst of living creatures, and if they see one merely touch the fodder placed in their stall they refuse it with disgust.” -Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, 77 AD Acknowledgments Though only one name can appear on the author’s line, there are many people whose support and help made this thesis possible and without whom, I would be nowhere. First, I must thank my family. As a child, my mother and father would try to stump me with a difficult math and geography question before tucking me into bed each night (and a few times they succeeded!). Thank you for giving birth to my fascination in all things international. Without you, none of this would have been possible. Second, I must thank a set of distinguished professors. Professor Mika LaVaque-Manty, thank you for giving me a chance to prove myself, even though I was a sophomore and studying abroad did not fit with the traditional path of thesis writers; thank you again for encouraging us all to think outside the box. My adviser, Professor Jenna Bednar, thank you for your enthusiastic interest in my thesis and having the vision to see what needed to be accentuated to pull a strong thesis out from the weeds. Professor Andrei Markovits, thank you for your commitment to your students’ work; I still believe in those words of the Moroccan scholar and will always appreciate your frank advice. -

San Marino Legal E

Study on Homophobia, Transphobia and Discrimination on Grounds of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Legal Report: San Marino 1 Disclaimer: This report was drafted by independent experts and is published for information purposes only. Any views or opinions expressed in the report are those of the author and do not represent or engage the Council of Europe or the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights. 1 This report is based on Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino , University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010. The latter report is attached to this report. Table of Contents A. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 B. FINDINGS 3 B.1. Overall legal framework 3 B.2. Freedom of Assembly, Association and Expression 10 B.3. Hate crime - hate speech 10 B.4. Family issues 13 B.5. Asylum and subsidiary protection 16 B.6. Education 17 B.7. Employment 18 B.8. Health 20 B.9. Housing and Access to goods and services 21 B.10. Media 22 B.11. Transgender issues 23 Annex 1: List of relevant national laws 27 Annex 2: Report of Dr Maria Gabriella Francioni, The legal and social situation concerning homophobia and discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation in the Republic of San Marino, University of the Republic of San Marino, Juridical Studies Department, 2010 31 A. Executive Summary 1. The Statutes "Leges Statuae Reipublicae Sancti Marini" that came into force in 1600 and the Laws that reform such Statutes represented the written source for excellence of the Sammarinese legal system. -

All Countries Visualization.Pdf

customs tariffamends principal hospitals board board control trade marks board hospital monetary authority marine board inserting next proceeds crime control over hospital insurance international sanctions government fees hospital fees merchant shipping medical practitioner legislative instruments authority application compliance authority reporting standard airworthiness directive pbssubsidised treatment radius centred thousand penalty authority procedures upon conviction column table tariff concession prudential standard column headed units imprisonment state territory specified column health research circle radius education institution copyright ministry meaning provided treatment cycle delegate chief millennium challenge liable upon statutory instrument penalty units affairs government financial supervision disciplinary committee Bermuda arising from legal person residence permit supervisory board traditional beer activity licence procedure provided approved maintenance rural municipality town council medicinal products regulatory authority requirements provided specified clause town clerk licensed premises established regulation district council close company specified employer supervision authority public sewer acts regulations insurance undertaking deleting words council resolution pouhere taonga pursuant procedure sleepovers performed information concerning eastern caribbean first reading financial markets punishable fine legal affairs exceeding months Australia statutory acknowledgement registrar general ministry legal antigua -

Uoc Sanità Pubblica

U.O.C. SANITÀ PUBBLICA Istituto per la Sicurezza Sociale DIPARTIMENTO PREVENZIONE U.O.S. Tutela dell’Ambiente Naturale e Costruito MONITORAGGIO DELLA QUALITÀ’ DELL’ARIA CON CAMPIONATORI PASSIVI RISULTATO DELLE CAMPAGNE ESEGUITE IN 10 SITI RAPPRESENTATIVI DELLE ZONE DI FALCIANO, ROVERETA E GUALDICCIOLO DELLA REP. DI S.MARINO 14 Maggio – 21 Maggio 2014 21 Maggio – 28 Maggio 2014 28 Maggio – 04 Giugno 2014 04 Giugno – 11 Giugno 2014 15 Settembre – 22 Settembre 2014 22 Settembre – 29 Settembre 2014 29 Settembre – 06 Ottobre 2014 06 Ottobre – 13 Ottobre 2014 13 Ottobre – 20 Ottobre 2014 Dott. Omar Raimondi Silvio Conti e Angelo Ercolani 1 REPUBBLICA DI SAN MARINO Sede legale del Dipartimento Prevenzione Sede tecnica del Dipartimento Prevenzione Sede distaccata UOS Sanità Veterinaria e Igiene Alimentare Via Scialoja 20 Via La Toscana 3 Strada del Lavoro 29 47893 Borgo Maggiore 47893 Borgo Maggiore 47892 Gualdicciolo Repubblica di San Marino Repubblica di San Marino Repubblica di San Marino T.+378(0549)994505- F +378 (0549) 994355 T. +378 (0549) 904614- F + 378 (0549) 953965 e-mail [email protected] www.salute.sm U.O.C. SANITÀ PUBBLICA Istituto per la Sicurezza Sociale 1) Premessa La presente relazione presenta i risultati delle campagne di monitoraggio eseguite a seguito delle numerose segnalazioni ed esposti rivolti al Dipartimento Prevenzione, che lamentavano disagio per la presenza di emissioni odorigene nei luoghi di residenza e di lavoro. Dopo le necessarie indagini preliminari e la conferma del problema denunciato sono state programmate due campagne di monitoraggio (dal 14/05 all’11/06/2014; dal 15/09 al 20/09/ al 20/10/2014) con esposizione settimanale di campionatori passivi mirati al campionamento dei Composti Organici Volatili, viste le particolari attività presenti in zona. -

Urban Society and Communal Independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy

Urban society and communal independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy Paul Oldfield Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. The University of Leeds The School of History September 2006 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks for the help of so many different people, without which there would simply have been no thesis. The funding of the AHRC (formerly AHRB) and the support of the School of History at the University of Leeds made this research possible in the first place. I am grateful too for the general support, and advice on reading and sources, provided by Dr. A. J. Metcalfe, Dr. P. Skinner, Professor E. Van Houts, and Donald Matthew. Thanks also to Professor J-M. Martin, of the Ecole Francoise de Rome, for his continual eagerness to offer guidance and to discuss the subject. A particularly large thanks to Mr. I. S. Moxon, of the School of History at the University of Leeds, for innumerable afternoons spent pouring over troublesome Latin, for reading drafts, and for just chatting! Last but not least, I am hugely indebted to the support, understanding and endless efforts of my supervisor Professor G. A. Loud. His knowledge and energy for the subject has been infectious, and his generosity in offering me numerous personal translations of key narrative and documentary sources (many of which are used within) allowed this research to take shape and will never be forgotten. -

Iv-Agosto-2007.Pdf 365KB

IV Settembre 2007 - Anno I CF e Periodico a cura dell’Ente Cassa di Faetano zi ti numerose iniziative, alcune delle quali sono settori ed interessi molto diversi, tuttavia una o illustrate anche su queste pagine, mentre presenza significativa dei Soci alle iniziative n altri importanti progetti prenderanno avvio. dell’Ente rappresenta per noi un obiettivo Probabilmente ve ne state accorgendo an- desiderato e perseguito, oltre che un inco- La parola al Presidente che dagli inviti che vi giungono con frequen- raggiamento a proseguire in un’attività che si UN AUTUNNO RICCO za sempre maggiore. Non si tratta di inviti di fa sempre più intensa e complessa. DI GRANDI circostanza, spediti per pura formalità; al Il nostro Ente sta crescendo nel numero APPUNTAMENTI contrario vogliono essere delle opportunità e nella qualità delle iniziative proposte e si concrete offerte a tutti noi, non solo per so- sta rivelando sempre più una risorsa per la L’Ente Cassa di Faetano si cializzare ma anche per conoscere, per nostra Repubblica. Di questo crediamo sia appresta a vivere un autunno gustare, per crescere. E’ evidente che non lecito andare giustamente fieri. veramente “caldo” nel corso del tutti i Soci potranno partecipare a tutte le quale giungeranno a realizzazione iniziative proposte che peraltro spaziano in ARTE PER MARE: SULLE ORME DEI SANTI MARINO E LEONE Tra gli eventi destinati a lasciare un segno natale sono fino ad oggi scarse, la città di Salona profondo nella Repubblica si colloca in un posto al di là dal mare e Rimini, sulla costa opposta, di rilievo la mostra dedicata ai Santi Marino e offrono una sicura base di partenza per l’avvio del Leone.“Arte per mare - Dalmazia, Titano e Mon- percorso espositivo. -

Match Press Kits

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2021/22 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS San Marino Stadium - Serravalle Sunday 5 September 2021 20.45CET (20.45 local time) San Marino Group I - Matchday 5 Poland Last updated 05/09/2021 10:58CET EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Squad list 3 Match officials 5 Match-by-match lineups 6 Legend 8 1 San Marino - Poland Sunday 5 September 2021 - 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Match press kit San Marino Stadium, Serravalle Previous meetings Head to Head FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Ales. Della Valle 22; Zieliński 10, 66, 10/09/2013 QR (GS) San Marino - Poland 1-5 Serravalle Błaszczykowski 23, Sobota 34, Mierzejewski 75 Lewandowski 21 (P), 50 (P), Piszczek 28, 26/03/2013 QR (GS) Poland - San Marino 5-0 Warsaw Teodorczyk 61, Kosecki 90+2 FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Boguski 1, 27, Smolarek 18, 60, 72, 81, Lewandowski 43, 01/04/2009 QR (GS) Poland - San Marino 10-0 Kielce Jeleń 51, M. Lewandowski 63, Saganowski 88 Smolarek 36, 10/09/2008 QR (GS) San Marino - Poland 0-2 Serravalle Lewandowski 68 UEFA EURO 2004 Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Szymkowiak 3, Ostrowiec 02/04/2003 PR (GS) Poland - San Marino 5-0 Kosowski 26, Kuźba Swietokrzyski 54, 90+3, Karwan 81 Kaczorowski 75, 07/09/2002 PR (GS) San Marino - Poland 0-2 Serravalle Kukiełka 88 FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Lesniak 52, 80, 19/05/1993 QR (GS) San Marino - Poland 0-3 Serravalle Warzycha 57 28/04/1993 QR (GS) Poland - San Marino 1-0 Lodz Furtok 71 Final Qualifying Total tournament Home Away Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA Total San Marino 4 0 0 4 4 0 0 4 - - - - 8 0 0 8 1 33 Poland 4 4 0 0 4 4 0 0 - - - - 8 8 0 0 33 1 2 San Marino - Poland Sunday 5 September 2021 - 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Match press kit San Marino Stadium, Serravalle Squad list San Marino Current season Overall Qual. -

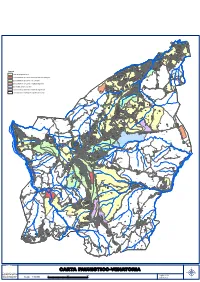

1:12.000 M U.G.R.A.A

Rovereta Dogana Fornace Falciano Ca' Valentino Campolungo Ranco Mauro Legenda Galazzano Ca' Ragni La Creta Oasi di ripopolamento Bosche Mondarco Saponaia Zanetta Zona di divieto di caccia - Riserva Naturale Integrale Torraccia Crete Ca' Marozzo Ponte Mellini Rancidello Zona di divieto di caccia - Area Parco Ca' Mercato Ca' Mazzola Piandolano Zona di divieto di caccia - Impianto Sportivo Rancaglia Cinque Vie Zona addestramento cani Olivella Ciarulla Zone di caccia destinate alla sola migratoria Molino Zone di caccia controllata e gestione sociale Serravalle Sant' Andrea Laiala Poggio Ruggine Ca' Baldino Coste Casvir Laghi Monte Olivo Le Tane Ca' Borgo San Michele Lesignano Grotte Valle Giurata Rancione Seggiano Fiorina Lagucci Ranco Pozzo delle Campore Ventoso Il Benefizio Cailungo di Sotto Ca' Tabarrino Serra Macero Serra Paradiso Paderna La Schiera Torraccia La Ciuffa Gualdicciolo Brugneto Toscana Ca' Giannino Ca' Carlo Ca' Gozi Ca' Taliano Il Grasso Gaviano Ca' Vagnetto Ca' Bartoletto Sterpeto Ginestre Molino dei Frati Moricce Ca' Riccio Ca' Amadore Cailungo di Sopra Domagnano Ca' Melone Montelupo Brandolina Fiumicello Tavolucci Valdicella Ca' Bertone Ca' Baudasso Ca' Martino Campagnaccio Acquaviva La Morra Il Fosso Monte Cerreto Colombaia Calintufo Bottaccione Piandavello Ca' Bugli Casetti Boschetti Molino della Genga Poggiolo Fiumicello Ca' Nino Casetta Valdragone Sotto Corianino Molino Magi Bigelli Gengone Vignale Baldasserona Fornace Borgo Maggiore Serrate Caitasso La Chiesuola Montalbo La Costa Cerreto Gaggio Ca' Moraccino Friginetto -

San Marino, Lì 10/04/2018 Ordine Del Giorno Considerate Le Disposizioni Di ENAC Relative Alle Misure Di Sicurezza in Materia Di

San Marino, lì 10/04/2018 Ordine del Giorno Considerate le disposizioni di ENAC relative alle misure di sicurezza in materia di ostacoli e po tenziali pericoli per i velivoli dell'aeroporto internazionale di Rimini e San Marino, conseguenti al recepimento dei regolamenti tecnici internazionali indicati nella propria relazione tecnica pubblicata e reperibile su tutti i bollettini dei comuni limitrofi alla Repubblica di San Marino in sieme alle mappe di vincolo dei territori interessati; valutato che tale relazione e le relative mappe di "vincolo e limitazioni relative agli ostacoli e ai pericoli per la navigazione aerea" interessano un raggio di circa 15 km attorno all'aeroporto Fellini, e ricadono quindi (mappe PC01-A e PC01-C) su buona parte del territorio sammarinese indicativamente da Dogana, Serravalle, Faetano, Cai/ungo, Valdragone, Domagnano fino a Borgo Maggiore; considerato quindi che, una volta approvate definitivamente, secondo tali mappe anche il no stro territorio, oltre CI quello di tutti i comuni limitrofi che circondano la RepubblicCl, si trove rebbe CI subire IImitClzioni importanti sugli strumenti urbClnistici e piani regolatori, nonché su numerose tipologie di costruzioni che sarebbero da sottoporre ad autorizzazione di ENAC per la loro realizzazione (Iaghettl artificiali, coltivazioni agricole, attività industriali, antenne ed appa rati radioelettricì irradianti, impianti fotovoltaici ed eolici ... ); con la volontà di valutare ed approfondire tutti I risvolti ed i possibili impatti sullo sviluppo eco nomico di