African Music Vol 2 No 1(Seb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection

Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division at the Library of Congress Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 2004 Table of Contents Introduction...........................................................................................................................................................iii Biographical Sketch...............................................................................................................................................vi Scope and Content Note......................................................................................................................................viii Description of Series..............................................................................................................................................xi Container List..........................................................................................................................................................1 FLUTES OF DAYTON C. MILLER................................................................................................................1 ii Introduction Thomas Jefferson's library is the foundation of the collections of the Library of Congress. Congress purchased it to replace the books that had been destroyed in 1814, when the Capitol was burned during the War of 1812. Reflecting Jefferson's universal interests and knowledge, the acquisition established the broad scope of the Library's future collections, which, over the years, were enriched by copyright -

Bone Flutes and Whistles from Archaeological Sites in Eastern North America

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 12-1976 Bone Flutes and Whistles from Archaeological Sites in Eastern North America Katherine Lee Hall Martin University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Martin, Katherine Lee Hall, "Bone Flutes and Whistles from Archaeological Sites in Eastern North America. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1976. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1226 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Katherine Lee Hall Martin entitled "Bone Flutes and Whistles from Archaeological Sites in Eastern North America." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in Anthropology. Charles H. Faulkner, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Major C. R. McCollough, Paul W . Parmalee Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Katherine Lee Hall Mar tin entitled "Bone Flutes and Wh istles from Archaeological Sites in Eastern North America." I recormnend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a maj or in Anthropology. -

The Shakuhachi and the Ney: a Comparison of Two Flutes from the Far Reaches of Asia

1 The Shakuhachi and the Ney: A Comparison of Two Flutes from the Far Reaches of Asia Daniel B. RIBBLE English Abstract. This paper compares and contrasts two bamboo flutes found at the opposite ends of the continent of Asia. There are a number of similarities between the ney, or West Asian reed flute and the shakuhachi or Japanese bamboo flute, and certain parallels in their historical development. even though the two flutes originated in completely different socio-cultural contexts. One flute developed at the edge of West Asia, and can be traced back to an origin in ancient Egypt, and the other arrived in Japan from China in the 8 th century and subsequently underwent various changes over the next millenium. Despite the differences in the flutes today, there may be some common origin for both flutes centuries ago. Two reed·less woodwinds Both flutes are vertical, endblown instruments. The nay, also spelled ney, as it is referred to in Turkey or Iran, and as the nai in Arab lands, is a rim blown flute of Turkey, Iran, the Arab countries, and Central Asia, which has a bevelled edge made sharp on the inside, while the shakuhachi is an endblown flute of Japan which has a blowing edge which is cut at a downward angle towards the outside from the inner rim of the flute. Both flutes are reed less woodwinds or air reed flutes. The shakuhachi has a blowing edge which is usually fitted with a protective sliver of water buffalo horn or ivory, a development begun in the 17 th century. -

Malagasy Music and Musical Instruments: an Alternative Key to Linguistic and Cultural History

Malagasy music and musical instruments: an alternative key to linguistic and cultural history MRAC, Tervuren, October 9th, 2009 Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation Introduction I Madagascar has a wide range of musical practices and musical instruments which can be linked to a history of peopling and contact These start with the remarkable vocal polyphony of the Vazimba/Mikea Austronesian instruments and musical styles still predominate but trade and settlement have brought further elements from the East African coast, beginning with coastal Bantu and reflecting the specifically Swahili maritime era trade contacts also reflect Indian, Arab and European instruments and practice the mixed musical culture has also been carried to other Indian Ocean islands Methodological issues • Musical instruments are a highly conservative form of material culture; musical practice often so. • Analytically they resemble zoogeography as a tool for analysis of prehistory • Musical instruments diffusing from one culture to another often retain names and performance styles of the source culture • Geographically bounded regions, such as islands, are often easier to unpick than contiguous mainland. Hence the importance of island biogeography • As a consequence, musical cultures in Madagascar can be used to create a chronostratigraphic map of the culture layers that compose its present-day society • The presentation will link these distributions and where possible, their names, to the putative origins to show how cultural layers and chronostratigraphy -

Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection

Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division at the Library of Congress Dayton C. Miller Flute Collection LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 2004 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... iii Biographical Sketch.............................................................................................................................................. vi Scope and Content Note..................................................................................................................................... viii Description of Series............................................................................................................................................. xi Container List ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 FLUTES OF DAYTON C. MILLER............................................................................................................... 1 ii Introduction Thomas Jefferson's library is the foundation of the collections of the Library of Congress. Congress purchased it to replace the books that had been destroyed in 1814, when the Capitol was burned during the War of 1812. Reflecting Jefferson's universal interests and knowledge, the acquisition established the broad scope of the Library's future collections, which, over the years, were enriched by copyright -

The Use of Traditional Japanese Music As An

THE USE OF TRADITIONAL JAPANESE MUSIC AS AN INSPIRATION FOR MODERN SAXOPHONE COMPOSITIONS: AN INTERPRETIVE GUIDE TO JOJI YUASA’S NOT I BUT THE WIND… AND MASAKAZU NATSUDA’S WEST, OR EVENING SONG IN AUTUMN BY CHRISTOPHER BRYANT ANDERSON DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Debra Richtmeyer, Chair Associate Professor Erik Lund, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Bruno Nettl Associate Professor J. David Harris ABSTRACT The use of non-Western music, particularly the traditional music of Japan, as the impetus for Western compositions has become increasingly common in music for saxophone since 1970. Many of the composers who have undertaken this fusion of styles are of Japanese nationality, but studied composition in Western conservatories and schools of music. Two composers who have become known for the use of elements from Japanese music within their compositions intended for Western instruments and performers are Joji Yuasa and Masakazu Natsuda. The aim of this study is to examine the manners in which these two composers approached the incorporation of Japanese musical aesthetics into their music for the saxophone. The first part of the document examines Joji Yuasa’s Not I, but the wind…, which uses the shakuhachi flute as its stylistic inspiration. A history and description of the shakuhachi flute, as well as the techniques used to create its distinctive musical style are provided. This is followed by a detailed examination of the manner in which the composer utilizes these stylistic elements within the composition, and a performance guide that stipulates how these elements should be interpreted by saxophonists. -

{FREE} Flute Ebook, Epub

FLUTE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Galway | 256 pages | 01 Apr 2003 | KAHN & AVERILL | 9781871082135 | English | London, United Kingdom flute | Definition, History, & Types | Britannica Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica Encyclopaedia Britannica's editors oversee subject areas in which they have extensive knowledge, whether from years of experience gained by working on that content or via study for an advanced degree See Article History. Britannica Quiz. A Study of Composers. What composer wrote symphonies and other major works before he was 13 years old? Get exclusive access to content from our First Edition with your subscription. Subscribe today. Learn More in these related Britannica articles:. Sound is generated by different methods in the aerophones designated as flutes and reeds in the Sachs-Hornbostel system. In flutes, the airstream is directed against a sharp edge; in reeds, the air column in the tube is caused to vibrate between beating…. Flute s were ubiquitous in antiquity. In early depictions, they are sometimes confused with reedpipes. What is thought to be the earliest example of a Western flute was discovered in at Hohle Fels cave near Ulm, Germany. The instrument, made of a vulture bone…. The Renaissance recorder blended well in consort but was weak in its upper register and needed modification to meet the demand for an expressive melodic style. The very nature of the instrument, with its lack of lip control, prevented much dynamic control, but the…. History at your fingertips. In a regional dialect of Gujarati, a flute is also called Pavo. -

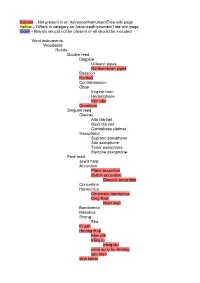

Differs in Category on Advancedinstrumenttree Wiki Page Violet – Brands Should Not Be Present Or All Should Be Included

Salmon – Not present in on AdvancedInstrumentTree wiki page Yellow – Differs in category on AdvancedInstrumentTree wiki page Violet – Brands should not be present or all should be included Wind instruments Woodwind Reeds Double reed Bagpipe Uilleann pipes Northumbrian pipes Bassoon Kortholt Contrabassoon Oboe English horn Heckelphone Kèn bầu Crumhorn Singular reed Clarinet Alto clarinet Bass clarinet Contrabass clarinet Saxophone Soprano saxophone Alto saxophone Tenor saxophone Baritone saxophone Free reed Jew's harp Accordion Piano accordion Button accordion Diatonic accordion Concertina Harmonica Chromatic harmonica Ðing Nam khèn meò Bandoneón Melodica Sheng Sho Ki pah Hmông flute tràm plè trắng lu trắng jâu pang gu ly hu Hmông sáo meò dinh taktàr Khen la´ Flute Fipple flutes Transverse flute Piccolo Alto flute Sáo trúc (under 'Other flutes') Vertical flute Pí thiu Recorder Garklein recorder Sopranino recorder Alto recorder / Treble recorder Tenor recorder Bass recorder / F-bass recorder Great bass recorder / C-bass recorder Contrabass recorder Subcontrabass recorder Bansuri Willow flute Shakuhachi Tin whistle Slide whistle Other flutes Pan flute Syrinx Nai Đing Buốt saó ôi flute Tieu flute Ocarina Nose flute k'long pút (under 'Other instruments') Brass Valved brass instruments Trumpet Cornet Flugelhorn Mellophone Horn French horn Baritone horn Tenor horn (Alto horn) Tuba Euphonium Sousaphone Wagner tuba Slide brass instruments Trombone Bass trombone Valve trombone Sackbut Keyed brass instruments Serpent Cornett Natural brass instruments -

A Supplementary Book of Chinese Music for The

A SUPPLEMENTARY BOOK OF CHINESE MUSIC FOR THE SUZUKI FLUTE STUDENT D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicole Marie Charles, M.Mus. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2010 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Katherine Borst Jones, Advisor Professor James Hill Professor Udo Will Copyright by Nicole Marie Charles 2010 i. ABSTRACT Created by Toshio Takahashi and Shinichi Suzuki, Suzuki Flute School Volume 1 contains a variety of music for the beginner flutist. Children‘s songs, folk music, and romantic and baroque music from Japan, France, America, and Germany provide beautiful tunes for the students to learn. Furthermore, beautiful sound is taught through tonalization, and beautiful character through strong relationships among the parent, teacher, and child. Having taught Suzuki flute classes at the Ohio Contemporary Chinese School (OCCS) since 2003, I‘ve had the opportunity to learn about the beautiful Chinese culture. But I have found that many children of Chinese descent have very little exposure to traditional Chinese music and children‘s songs. Due to historical patterns in China of disposing or recycling music, many of their parents do not know many Chinese songs (at least those without political undertones). The Suzuki method itself does not contain any Chinese songs. The purpose of this document is to provide a supplementary book of Chinese flute music for my students at the OCCS, one tailored to coincide with the pedagogical points of Suzuki Flute School Volume 1. -

An Exhibition of Chinese Musical Instruments and Artefacts: Musical Continuity from Antiquity to the Present

THE MUSIC ARCHIVE OF MONASH UNIVERSITY presents AN EXHIBITION OF CHINESE MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND ARTEFACTS: MUSICAL CONTINUITY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE PRESENT in the Foyer of the Music Auditorium, Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music launched by Ms ZOU BIN, Cultural Consul of the Consulate-General of the P.R China in Melbourne 12:30pm, Thursday 20 September 2018 Court scholars of the Zhou dynasty (1046-256 BCE) may be credited with inventing the world's earliest system of musical instrument classification. The Zhou Li text identifies eight distinct resonating materials used in instrument construction: metal, stone, clay, skin, silk, wood, gourd and bamboo hence the classification is named ba yin, meaning 'eight tone'. (Alan R. Thrasher. 2000. Chinese Musical Instruments. New York: OUP) Instruments made from each of these eight materials controlled one of the dances performed at rituals, which in turn could induce one of the eight winds emanating from each of the eight compass points shown in the diagram. The eight-part concept of music and instruments were thus part of the calendrical system, the weather, the seasons, and even cosmological thought. From Joseph Needham and Kenneth Robinson. 1962. ‘Sound Acoustics’, Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1. Physics. UK: Cambridge University Press, pp155-56: “First, autumn is the season when the Yang forces of nature are in retreat, and bells or metal slabs were the instruments sounded when a commander ordered his troops to retire. In winter there occurred one of the most solemn ceremonies of the year, when the sun was assisted over the crisis of the solstice by the help of sympathetic magic. -

Modeling Chinese Musical Instuments

Mdeling Chinese Musical Instmmenti Andrew Homer and Lydia Ayers Department of Computer Science, Hong Kong Universi~ of Science and Technology Clear Water Bay, Kowloun, Hong Kong emai[: homer@ CS.ust. hk and layers@cs. ust, hk Abstracti We have modeled more than twenty Chinese traditional and folk instruments using Csound, and used traditional scores for each instrument as examples. We will play musical excerpts using the Csound designs for our demo, as well as playing severaf of the smaller acoustic instruments “live” for comparison. CH~ESE ~STRUMENTS Previous work on modeling instruments has primarily focused on simulating western instruments. Researchers have also explored the acoustics of the Japanese shakuhuchi and large Chinese bells. They have not devoted as much attenlion to the other Chinese instruments. Chinese wind instruments include a range of colorful instruments with distinctive characters. The dizi is the most common of the Chinese flutes, and it has a bright buzzing quality produced by a rice paper membrane glued over a special hole. The di:i often takes a leading role in ensembles, where its bright timbre allows it to cut through even large groups. Other types of Chinese flutes include the xiao (vertical flute), pai.~iao (panpipes) and xun (-ocarina). The bawu is a folk instrument, easier to play than the dizi. Players hold the bawu transversely like the fluLe, but with the player’s mouth completely coveting the blowhole, which has a narrow triangular tongue cut into a copper strip covering the hole. The copper tongue vibrates when the player blows producing a sound similar to a recorder or clarinet, but more mellow.