University of California Riverside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro Outline

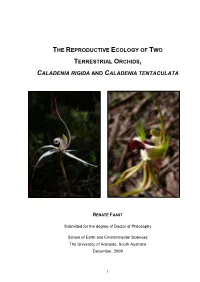

THE REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF TWO TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS, CALADENIA RIGIDA AND CALADENIA TENTACULATA RENATE FAAST Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of Adelaide, South Australia December, 2009 i . DEcLARATION This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution to Renate Faast and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis (as listed below) resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University's digital research repository, the Library catalogue, the Australasian Digital Theses Program (ADTP) and also through web search engines. Published works contained within this thesis: Faast R, Farrington L, Facelli JM, Austin AD (2009) Bees and white spiders: unravelling the pollination' syndrome of C aladenia ri gída (Orchidaceae). Australian Joumal of Botany 57:315-325. Faast R, Facelli JM (2009) Grazrngorchids: impact of florivory on two species of Calademz (Orchidaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 57:361-372. Farrington L, Macgillivray P, Faast R, Austin AD (2009) Evaluating molecular tools for Calad,enia (Orchidaceae) species identification. -

Herbert Spencer in His Own Words

Herbert Spencer In His Own Words On materialism: "What is Comte's professed aim? To give a coherent account of the progress of human conceptions. What is my aim? To give a coherent account of the progress of the external world. Comte proposes to describe the necessary and the actual, filiation of ideas. I propose to describe the necessary, and the actual, filiation of things. Comte professes to interpret the genesis of our knowledge of nature. My aim is to interpret . the genesis of the phenomena which constitute nature. The one is subjective. The other is objective" (1904, p.570). "The average opinion in every age and country is a function of the social structure in that age and country" (1891, p. 390). "There can be no complete acceptance of sociology as a science, so long as the belief in a social order not conforming to natural law survives" (1891, p. 394). Herbert Spencer (1867, 327) first posited a unity of the evolutionary process: “Evolution, then, under its primary aspect, is a change from a less coherent form to a more coherent form consequent on the dissipation of motion and integration of matter. This proves to be a character displayed equally in those earliest changes which the Universe at large is supposed to have undergone, and in those latest changes which we trace in society and the products of social life.” On the division of labor: As the population becomes more diverse in terms of occupation, experience, wealth, interests, and values, the people also become more dependent upon one another. -

Plant Rarity: Species Distributional Patterns, Population Genetics, Pollination Biology, and Seed Dispersal in Persoonia (Proteaceae)

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Plant rarity: species distributional patterns, population genetics, pollination biology, and seed dispersal in Persoonia (Proteaceae) Paul D. Rymer University of Wollongong Rymer, Paul D, Plant rarity: species distributional patterns, population genetics, pollination biology, and seed dispersal in Persoonia (Proteaceae), PhD thesis, School of Biological Sciences, University of Wollongong, 2006. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/634 This paper is posted at Research Online. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/634 1 Plant rarity: species distributional patterns, population genetics, pollination biology, and seed dispersal in Persoonia (Proteaceae). PhD Thesis by Paul D. Rymer B.Sc. (Hons) – Uni. of Western Sydney School of Biological Sciences UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG 2006 2 DECLARATION This thesis is submitted, in accordance with the regulations of the University of Wollongong, in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The work described in this thesis was carried out by me, except where otherwise acknowledged, and has not been submitted to any other university or institution. 3 “Yes, Duckie, you’re lucky you’re not Herbie Hart who has taken his Throm-dim-bu-lator apart” (Dr. Seuss 1973) 4 Abstract An understanding of rarity can provide important insights into evolutionary processes, as well as valuable information for the conservation management of rare and threatened species. In this research, my main objective was to gain an understanding of the biology of rarity by investigating colonization and extinction processes from an ecological and evolutionary perspective. I have focused on the genus Persoonia (family Proteaceae), because these plants are prominent components of the Australian flora and the distributional patterns of species vary dramatically, including several that are listed as threatened. -

FORTY YEARS of CHANGE in SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES Catherine Cumberland University of New Mexico - Main Campus

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Biology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Summer 7-15-2019 FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES Catherine Cumberland University of New Mexico - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cumberland, Catherine. "FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES." (2019). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/biol_etds/321 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Catherine Cumberland Candidate Biology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Kenneth Whitney, Ph.D., Chairperson Scott Collins, Ph.D. Paula Klientjes-Neff, Ph.D. Diane Marshall, Ph.D. Kelly Miller, Ph.D. i FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES by CATHERINE CUMBERLAND B.A., Biology, Sonoma State University 2005 B.A., Environmental Studies, Sonoma State University 2005 M.S., Ecology, Colorado State University 2014 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy BIOLOGY The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July, 2019 ii FORTY YEARS OF CHANGE IN SOUTHWESTERN BEE ASSEMBLAGES by CATHERINE CUMBERLAND B.A., Biology B.A., Environmental Studies M.S., Ecology Ph.D., Biology ABSTRACT Changes in a regional bee assemblage were investigated by repeating a 1970s study from the U.S. -

Changing Paradigms in Insect Social Evolution: Insights from Halictine and Allodapine Bees

ANRV297-EN52-07 ARI 18 July 2006 2:13 V I E E W R S I E N C N A D V A Changing Paradigms in Insect Social Evolution: Insights from Halictine and Allodapine Bees Michael P. Schwarz,1 Miriam H. Richards,2 and Bryan N. Danforth3 1School of Biological Sciences, Flinders University, Adelaide S.A. 5001, Australia; email: Michael.Schwarz@flinders.edu.au 2Department of Biological Sciences, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON L2S 3A1, Canada; email: [email protected] 3Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007. 52:127–50 Key Words The Annual Review of Entomology is online at sex allocation, caste determination, phylogenetics, kin selection ento.annualreviews.org This article’s doi: Abstract 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.150950 Until the 1980s theories of social insect evolution drew strongly Copyright c 2007 by Annual Reviews. on halictine and allodapine bees. However, that early work suffered All rights reserved from a lack of sound phylogenetic inference and detailed informa- 0066-4170/07/0107-0127$20.00 tion on social behavior in many critical taxa. Recent studies have changed our understanding of these bee groups in profound ways. It has become apparent that forms of social organization, caste de- termination, and sex allocation are more labile and complex than previously thought, although the terminologies for describing them are still inadequate. Furthermore, the unexpected complexity means that many key parameters in kin selection and reproductive skew models remain unquantified, and addressing this lack of informa- tion will be formidable. -

The Concept of Social Metabolism in Classical Sociology Theomai, Núm

Theomai ISSN: 1666-2830 [email protected] Red Internacional de Estudios sobre Sociedad, Naturaleza y Desarrollo Argentina Padovan, Dario The concept of social metabolism in classical sociology Theomai, núm. 2, 2000 Red Internacional de Estudios sobre Sociedad, Naturaleza y Desarrollo Buenos Aires, Argentina Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12400203 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto REVISTA THEOMAI / THEOMAI JOURNAL The concept of social metabolism in classical sociology Dario Padovan * Department of Sociology, University of Padua. E-mail: [email protected] 1. Introduction Recently, social metabolism has been defined as "the particular form in which societies establish and maintain their material input from and output to nature; the mode in which they organize the exchange of matter and energy with their natural environment" (1). However, among early sociologists the concept of social metabolism was widely adopted. At that time it was used to describe the same process: the exchange and the transformation of matter, energy, labour and knowledge carried out between the social system and the environmental system. But it did have various different meanings. For some authors it was one concrete way in which society was embedded in cosmic evolution, which simultaneously offered models to help understand how the social system functioned; for others it was a way of describing the exchange of energy and matter between society and nature, that which permitted the reproduction of the social system and of the social achievement needed for human advancement; for others again, social metabolism was one way in which society could renew its élite. -

Do Metaphors Evolve? the Case of the Social Organism

Roskilde University Do metaphors evolve? The case of the social organism Mouton, Nicolaas T.O. Published in: Cognitive Semiotics Publication date: 2013 Citation for published version (APA): Mouton, N. T. O. (2013). Do metaphors evolve? The case of the social organism. Cognitive Semiotics, V(1-2), 312. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Journal of Cognitive Semiotics, V(1-2): 312-348, http://www.cognitivesemiotics.com . Nico Mouton Roskilde University Do Metaphors Evolve? The Case of the Social Organism A long line of philosophers and social scientists have defended and extended the curious idea that collective entities – states and societies, cities and corporations – are biological organisms. In this article, I study a few short but spectacular episodes from the history of that metaphor, juxtapose mappings made in one era with correspondences conjured in other epochs, and reflect upon the reasons why they differ. -

Environmental Factors Influencing Fruit Production and Seed Biology of the Critically Endangered Persoonia Pauciflora (Proteaceae)

Folia Geobot https://doi.org/10.1007/s12224-019-09343-6 Environmental factors influencing fruit production and seed biology of the critically endangered Persoonia pauciflora (Proteaceae) Nathan J. Emery & Catherine A. Offord # The Author(s) 2019 Abstract The factors that influence seed production incubated seeds. Our study highlights the importance of and seed dormancy in rare plant species are crucial to ensuring appropriate biotic pollen vectors are present in their conservation yet are often poorly understood. In the local landscape for maximising viable fruit produc- this study, we examined the breeding system and seed tion for this species. In addition, our data indicate that biology of the critically endangered Australian endemic recruitment will most likely occur after the endocarp has species Persoonia pauciflora through a series of exper- suitably weakened, allowing physiological dormancy of iments. Pollinator visitation surveys and manipulative the embryo to be relaxed and germination to commence hand-pollination treatments were conducted to investi- following summer temperatures. gate the breeding system and subsequent seed produc- tion. We used an experimental seed burial to examine Keywords breeding system . endocarp . Leioproctus . the breakdown of the woody endocarp and changes to Persoonia pauciflora . pollination . seed germination germination over time. Seed germination response un- der simulated local seasonal conditions was also exam- ined. Persoonia pauciflora was found to be predomi- nantly pollinated by native bees, and cross-pollinated Introduction flowers produced significantly more mature fruit (18 ± 3%) than self-pollination treatments (2–3%). The aver- Numerous factors operating at a range of spatial scales can age strength of P. pauciflora pyrenes buried in soil affect plant abundance or rarity (Schemske et al. -

Promoting Mental Health

Promoting Mental Health ■ ■ CONCEPTS EMERGING EVIDENCE PRACTICE A Report of the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and The University of Melbourne Promoting Mental Health ■ ■ CONCEPTS EMERGING EVIDENCE PRACTICE A Report of the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and The University of Melbourne Editors: Helen Herrman Shekhar Saxena Rob Moodie WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice : report of the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation and the University of Melbourne / [editors: Helen Herrman, Shekhar Saxena, Rob Moodie]. 1.Mental health 2.Health promotion 3.Evidence-based medicine 4.Health policy 5.Practice guidelines 6.Developing countries I.Herrman, Helen. II.Saxena, Shekhar. III.Moodie, Rob. ISBN 92 4 156294 3 (NLM classification: WM 31.5) © World Health Organization 2005 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel: +41 22 791 2476; fax: +41 22 791 4857; email: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; email: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

The Biology and External Morphology of Bees

3?00( The Biology and External Morphology of Bees With a Synopsis of the Genera of Northwestern America Agricultural Experiment Station v" Oregon State University V Corvallis Northwestern America as interpreted for laxonomic synopses. AUTHORS: W. P. Stephen is a professor of entomology at Oregon State University, Corval- lis; and G. E. Bohart and P. F. Torchio are United States Department of Agriculture entomolo- gists stationed at Utah State University, Logan. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The research on which this bulletin is based was supported in part by National Science Foundation Grants Nos. 3835 and 3657. Since this publication is largely a review and synthesis of published information, the authors are indebted primarily to a host of sci- entists who have recorded their observations of bees. In most cases, they are credited with specific observations and interpretations. However, information deemed to be common knowledge is pre- sented without reference as to source. For a number of items of unpublished information, the generosity of several co-workers is ac- knowledged. They include Jerome G. Rozen, Jr., Charles Osgood, Glenn Hackwell, Elbert Jay- cox, Siavosh Tirgari, and Gordon Hobbs. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Leland Chandler and Dr. Jerome G. Rozen, Jr., for reviewing the manuscript and for many helpful suggestions. Most of the drawings were prepared by Mrs. Thelwyn Koontz. The sources of many of the fig- ures are given at the end of the Literature Cited section on page 130. The cover drawing is by Virginia Taylor. The Biology and External Morphology of Bees ^ Published by the Agricultural Experiment Station and printed by the Department of Printing, Ore- gon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, 1969. -

A Causative-Diagnostic Analysis of Turkey's Majcr Prcblems And

A CAUSATIVE-DIAGNOSTIC ANALYSIS OF TURKEY'S MAJCR PRCBLEMS AND A CQUwUNICATIVE APPROACH TO THEIR SOLUTION (DEMOCRATIC PLANNING AND MASS COMMUNICATION) Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By ILHAN OZDIL, B.S. The Ohio State University 195U Approved by* VI Adviser Table of Contents Page Introduction • . • T± Propositions ...... .............................. Tl The Sti*ucture of the Study ...................... •▼'111 The irfethod uf the Study........................ • . lx The Vindication of the Topical Selection........... Xl P&A Diagnosis Chapter 1 A Brief Retrospect ........... 1 Chapter II About the Nature of the Kemalist Revolution .... 9 1. The Nature of Kemalisra........... 9 2. The idain Principles, Objectives and Reforms of the Kemalist Revolution 13 3. Turkish Revolution as a Far-reaching Democratic Educa tional Process ........... 16 Chapter III A Causative-Diagnostic Analysis of Sane Uajor Problems of Turkey.................................25 1. Agriculture ...................................... 35 A. Definition and description of the problem...... 35 B. Causative-diagnostic analysis of the problem . 1+1 C. Remedial proposals and their communicative bearings ............... 1+8 D. Present Situation......... 5U 2 • Industry 56 A* Definition and description of the problem ..... 56 B. Causative-diagnostic analysis of the problem . 63 C. Remedial proposals and their communicative bearings .......................................73 D. Present Situation ......... 76 3* Public Health and Social Welfare............. 79 A. Definition and description of the problem...... 79 B. Causative-diagnostic analysis of the problem . 82 C. Remedial proposals and their communicative bearings ..... ..................... .... 87 D. Present situation .... ..... 91 li. Politics and Democratization . ............. 98 A. Definition and description of the problem...... 98 B. -

Common Pollinator and Beneficial Insects of Victoria

Common Pollinator and Beneficial Insects of Victoria An identification and conservation guide Hymenoptera: Bees WPC WPC Blue-banded bee Chequered cuckoo bee Apidae Apidae WPC Hoelzer Alison Common spring bee European honey bee Colletidae Apidae WPC WPC Golden-browed resin bee Halictid bee (Lipotriches sp.) Megachilidae Halictidae Hymenoptera: Bees Alison Hoelzer Alison WPC Halictid bee Reed bee Halictidae Exoneura WPC Hoelzer Alison Hylaeus bee (bubbling) Large Lasioglossum sp. Colletidae Halictidae WPC WPC Leafcutter bee Red bee Megachilidae Halictidae Hymenoptera: Bees • Around 2,000 native bee species currently known. • Mostly found in sunny, open woodlands, gardens and meadows with lots of flowers. • Active when it is warm, fine and calm or only lightly breezy. • Nest in bare sandy soil, or cavities of dead wood or stone walls. • Size range: 5 mm to over 2 cm; colours: black, gold, red, yellow or green, often with stripes on abdomen. Blue-banded bee Blue-banded bee Amegilla sp. Amegilla sp. Hymenoptera: Wasps, Ants & Sawies Alison Hoelzer Alison WPC Ant Cream-spotted ichneumon wasp Formicidae Ichnuemonidae WPC WPC Cuckoo wasp European wasp Chrysididae Vespidae WPC WPC Flower wasp (female, wingless) Flower wasp (male) Tiphiidae Tiphiidae Hymenoptera: Wasps, Ants & Sawies WPC WPC Gasteruptiid wasp Hairy ower wasp Gasteruptiidae Scoliidae WPC WPC Orange ichneumon wasp Paper wasp Ichnuemonidae Vespidae WPC WPC Paper wasp Sawy adult Vespidae Tenthredinidae Hymenoptera: Wasps, Ants & Sawies • Around 8,000 native species currently known; many more undescribed. • Found in all habitats. Wasps lay eggs in leaf litter, cavities, bare soil or other insects; ants build nests underground or in trees; sawflies lay eggs under leaves.