Changing Paradigms in Insect Social Evolution: Insights from Halictine and Allodapine Bees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5.4 Insect Visitors to Marianthus Aquilonaris and Surrounding Flora

REPORT: Insect visitors to Marianthus aquilonaris and surrounding flora Nov 2-4, 2019 Kit Prendergast, Native bee scientist BSc First Class Honours, PhD researcher and Forrest Scholar On behalf of Botanica Consulting 1 REPORT: Insect visitors to Marianthus aquilonaris and surrounding flora Nov 2-4 2019 Kit Prendergast, Native bee scientist Background Marianthus aquilonaris (Fig. 1) was declared as Rare Flora under the Western Australian Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 in 2002 under the name Marianthus sp. Bremer, and is ranked as Critically Endangered (CR) under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN 2001) criteria B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v); C2a(ii) due to its extent of occurrence being less than 100 km2, its area of occupancy being less than 10 km2, a continuing decline in the area, extent and/or quality of its habitat and number of mature individuals and there being less than 250 mature individuals known at the time of ranking (Appendix A). However, it no longer meets these criteria as more plants have been found, and a recommendation has been proposed to be made by DBCA to the Threatened Species Scientific Committee (TSSC) to change its conservation status to CR B1ab(iii,v)+2ab(iii,v) (Appendix A), but this recommendation has not gone ahead (DEC, 2010). Despite its listing as CR under the Western Australian Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, the species is not currently listed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The main threats to the species are mining/exploration, track maintenance and inappropriate fire regimes (DEC, 2010). Fig. 1. Marianthus aquilonaris, showing flower, buds and leaves. -

Sensory and Cognitive Adaptations to Social Living in Insect Societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S

COMMENTARY COMMENTARY Sensory and cognitive adaptations to social living in insect societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S. van Zwedena A key question in evolutionary biology is to explain the solitarily or form small annual colonies, depending upon causes and consequences of the so-called “major their environment (9). And one species, Lasioglossum transitions in evolution,” which resulted in the pro- marginatum, is even known to form large perennial euso- gressive evolution of cells, organisms, and animal so- cial colonies of over 400 workers (9). By comparing data cieties (1–3). Several studies, for example, have now from over 30 Halictine bees with contrasting levels of aimed to determine which suite of adaptive changes sociality, Wittwer et al. (7) now show that, as expected, occurred following the evolution of sociality in insects social sweat bee species invest more in sensorial machin- (4). In this context, a long-standing hypothesis is that ery linked to chemical communication, as measured by the evolution of the spectacular sociality seen in in- the density of their antennal sensillae, compared with sects, such as ants, bees, or wasps, should have gone species that secondarily reverted back to a solitary life- hand in hand with the evolution of more complex style. In fact, the same pattern even held for the socially chemical communication systems, to allow them to polymorphic species L. albipes if different populations coordinate their complex social behavior (5). Indeed, with contrasting levels of sociality were compared (Fig. whereas solitary insects are known to use pheromone 1, Inset). This finding suggests that the increased reliance signals mainly in the context of mate attraction and on chemical communication that comes with a social species-recognition, social insects use chemical sig- lifestyle indeed selects for fast, matching adaptations in nals in a wide variety of contexts: to communicate their sensory systems. -

Halictus Scabiosae in FVG.Pdf

Bollettino Soc. Naturalisti “Silvia Zenari”, Pordenone 36/2012 pp. 147-156 ISSN 1720-0245 Laura Fortunato1 - Pietro Zandigiacomo1 Fenologia e preferenze florali di Halictus scabiosae (Rossi) in Friuli Venezia Giulia Riassunto: Halictus scabiosae (Rossi) (Hymenoptera, Halictidae) è un insetto impollinatore Apoideo piuttosto comune in Friuli Venezia Giulia. In questa nota si descrive la fenologia della specie e si indicano le piante erbacee in fiore visitate da femmine e maschi. Nel quadriennio 1997-2000, periodici campionamenti sulla presenza e sull’attività pronuba di questa specie sono stati condotti, fra marzo e settembre, in due ambienti friulani: a) un agroecosistema misto in area planiziale a Udine (loc. S. Osvaldo) con molti fattori di disturbo, b) un’area collinare a Pagnacco (UD) (loc. Villa Rizzani) con prati, pascoli e siepi. Inoltre, ulteriori osservazioni sulle piante bottinate sono state condotte nel periodo 2006-2012 in prati polifiti a Pagnacco e Tavagnacco (UD). Individui di H. scabiosae sono stati osservati ininterrottamente per un lungo periodo fra marzo e settembre; ciò è in accordo con quanto riportato in letteratura ove la specie è indicata come bivoltina. I dati raccolti suggeriscono che la prima generazione, composta prevalentemente da femmine, si sviluppa nel periodo maggio-giugno, mentre la seconda, composta da femmine e maschi, fra luglio e settembre. Le osservazioni condotte nei periodi 1997-2000 e 2006-2012 hanno permesso di rilevare che le piante maggiormente visitate da H. scabiosae appartengono alla famiglia Compositae, seguono poi piante di altre famiglie, quali Dipsacaceae e Labiatae. In particolare, le piante più visitate dalle femmine sono state Helianthus annuus e Taraxacum officinale, mentre i maschi sono stati rilevati frequentemente su Centaurea nigrescens ed Helianthus tuberosus. -

Diversity of Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) in and Around Namdapha National Park, with an Updated Checklist from Arunachal Pradesh, India

Rec. zool. Surv. India: Vol. 118(4)/ 413-425, 2018 ISSN (Online) : (Applied for) DOI: 10.26515/rzsi/v118/i4/2018/122129 ISSN (Print) : 0375-1511 Diversity of Bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) in and around Namdapha National Park, with an Updated Checklist from Arunachal Pradesh, India Jagdish Saini*, Kailash Chandra, Hirdesh Kumar, Dibya Jyoti Ghosh, S. I. Kazmi, Arajush Payra and C. K. Deepak Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700053, India; [email protected] Abstract The present study documents a preliminary checklist of bee diversity from Arunachal Pradesh, India based on literature study and the surveys undertaken during October, 2016 to July, 2017. Altogether, 49 species have been recorded belonging to 12 genera under 03 families viz. Apidae, Halictidae, and Megachilidae. Family Megachilidae, Genus Ceratina and 13 Keywords: Apidae, Bee diversity, Eastern Himalaya, Halictidae, Megachilidae species of bees are recorded first time from Arunachal Pradesh. Introduction The paper presents an updated checklist of superfamily Apoidea of Arunachal Pradesh. Family Megachilidae with Bees are considered to be the most effective insect in five species is recorded for the first time from Arunachal pollination service (Free, 1993; Torchio, 1990; Thakur Pradesh. Genus Ceratina Latreille is also recorded for the and Dongarwar, 2012; Raj et al., 2012). A sharp decline first time from Arunachal Pradesh. To understand the in bee population globally is been observed due to lack distribution knowledge of bees of eastern Himalaya it is of quality food resources, anthropogenic effects like impeccable that more intensive studies are required from habitat fragmentation, degradation, climate change and the region. -

Subfamily Halictinae: Bionomics

40 Chapter ll. General characteristics of the halictids bees pical), Eupetersia Bt-UttlCrN (Palaeotropical, witlr three subgenera), Micro- sphecodes EICKwoRl et STAGE (Neotropical), Ptilocleplis MICHENEn (Neotropi- -=l cal), arrd Sphecodes Lerngtlle (nearly cosmopolitan but absent in South America, with two subgenera). +r The followir.lg genera of the Halictinae inhabit the Palaearctic regiorr: Ceyla- 47[J lictus, Nontioie{es, Hclictus, Pachyhalictus, Seladonia, Thrincohalictus, Vestito- halicttts, Evylaeus, Lasioglossttm, Ctenonontia, Lucasielltts, Sphecode.s. In Europe, 268 species of almost all the genera listed above occur (except for large Palaeotropic genera Pachyhalictus and Ctenononia; each of which is represented in the Pa- laearctic region by few species). Only six genera (including Sphecodes) are repre- sented in Poland r,vhere 92 species of the Halictinae are recorded. j Subfamily Halictinae: bionomics Main kinds of nest patterns. The nest architecture of the Halictinae was studied in detail by SareceMl & MTCIIENER (1962), with taking into accountthe most of data existent by that tirne. These authors have distinguished 8 types arrd I I subtypes of halictine nests. In those groups one finds almost all known nest types properto burrowing bees (Figs.47-62). The most species build their nests in soil, although some of thern sporadically or constantly settle in rotten wood, e.g. some Augochlorini. Sorne species exhibit a great plasticity in the choice of place for nest construction. For exarnple, nests of Halicttts rubicundus were registered both in grourrd (BONel-lt, 1967b BATRA, 1968;and sotneotlrers), and in rotten wood (Ml- CHENËR& wrLLE, l96l). Halictipe nests are as a rule characterised by the presence of nest turrets, which are formed iu result of cerlerrtation of soil parlicles ott the walls of the en- trance passiug throrlgh a conical tumulus. -

Les Abeilles Des Graminées Ou Lipotriches Gerstaecker, 1858, Sensu Stricto (Hymenoptera Apoidea Halictidae Nomiinae) De La Région Orientale

Les abeilles des graminées ou Lipotriches Gerstaecker, 1858, sensu stricto (Hymenoptera Apoidea Halictidae Nomiinae) de la Région Orientale Document de Travail du 24 Décembre 2012, unpublished document ! par Alain PAULY (Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Département Entomologie, Rue Vautier 29, B-1000 Bruxelles, Belgique). Introduction Le genre Lipotriches sensu stricto est caractérisé par le plateau basal des tibias postérieurs des femelles incomplet. Les deux sexes ont le col du pronotum lamellé. Le calcar interne des tibias postérieurs est généralement scuplté par une crête lamellée continue et non des dents. La plupart des groupes de Lipotriches récoltent le pollen des graminées, ceux qui ont les soies des tibias postérieurs en lasso le récoltent exclusivement. On rencontre 58 espèces valides en Afrique plus une dizaine d’espèces nouvelles, et 28 espèces valides sont étudiées ici de la Région Orientale. Trois espèces atteignent le nord de l’Australie. Matériel et méthode Acronymes des collections étudiées (entre parenthèses le nom des personnes ayant aidé au prêt de matériel) : AMNH : American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA (J. S. ASCHER; E. L. QUINTER). BBMH: Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawai, USA (T. GONSALVES). BMNH : Natural History Museum, London, UK [anciennement British Museum (Natural History)] (G. ELSE; D. NOTTON). CAS: California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, USA (W.J. PULAWSKI). FSAG: Faculté Universitaire des Sciences Agronomiques, Gembloux, Belgique (E. HAUBRUGE). HNM: Magyar Nemzeti Museum, Budapest, Hongrie. HYAS : Entomological Laboratory, Hyogo University of Agriculture, Sesayama, Japon. IRSNB: Institut royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Bruxelles, Belgique (P. GROOTAERT ; J.L. BOEVE ; J. CONSTANT). ITZA : Instituut voor Taxonomische Zoologie, Amsterdam, Pays-Bas (W. -

Hymenoptera: Halictidae)

Neocorynurella, a New Genus of Augochlorine Bees from South America (Hymenoptera: Halictidae) Michael S. Engell and Barrett A. Klein2 1 Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 2 Exhibitions, American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York Abstract Neocorynurella Engel gen. n., a new sweat bee genus of the tribe Augochlorini (Halictidae), is described and figured from high altitudes in Colombia and Venezuela. The genus is distinguished from other augochlorine genera by the following combination of characters: galeal comb absent, epistomal sulcus obtuse, mouthparts not narrowed, preoccipital ridge rounded, pronotal dorsal and lateral ridges not carinate, pectinate inner hind tibia1 spur, strong basitibial plate, truncated marginal cell, and penis valve without a ventral prong. Two species are currently recognized in the group, Neocorynurella SPP- leyi Engel et Klein sp. n. and N. viridis Engel et Klein sp. 11. Modified key couplets are provided for Eickwort's key to the genera of Augochlorini in order to facilitate recognition of the new genus. The position of Neocorynurella in augochlorine phylogeny is briefly discussed. Key words: Augochlorini, bees, montane, Neocoryrzurelln, South America, taxonomy Introduction Bees of the tribe Augochlorini are restricted to the New World and have their greatest diversity in the tropics. The group is most easily recognized by the division of the pseudo- pygidial area of the female fifth tergum and by the absence of a pygidial plate in the male. The tribe is small, with approximately 500 described spccies, compared to its cosmopolitan sister tribe the Halictini (with over 2000 species). Despite their numerical size, the augo- chlorines exhibit a wide range of behavioral diversity. -

The Risk‐Return Trade‐Off Between Solitary and Eusocial Reproduction

Ecology Letters, (2015) 18: 74–84 doi: 10.1111/ele.12392 LETTER The risk-return trade-off between solitary and eusocial reproduction Abstract Feng Fu,1* Sarah D. Kocher2 and Social insect colonies can be seen as a distinct form of biological organisation because they func- Martin A. Nowak2,3,4 tion as superorganisms. Understanding how natural selection acts on the emergence and mainte- nance of these colonies remains a major question in evolutionary biology and ecology. Here, we explore this by using multi-type branching processes to calculate the basic reproductive ratios and the extinction probabilities for solitary vs. eusocial reproductive strategies. We find that eusociali- ty, albeit being hugely successful once established, is generally less stable than solitary reproduc- tion unless large demographic advantages of eusociality arise for small colony sizes. We also demonstrate how such demographic constraints can be overcome by the presence of ecological niches that strongly favour eusociality. Our results characterise the risk-return trade-offs between solitary and eusocial reproduction, and help to explain why eusociality is taxonomically rare: eusociality is a high-risk, high-reward strategy, whereas solitary reproduction is more conserva- tive. Keywords Ecology and evolution, eusociality, evolutionary dynamics, mathematical biology, social insects, stochastic process. Ecology Letters (2015) 18: 74–84 There have been a number of attempts to identify some of INTRODUCTION the key ecological factors associated with the evolution of Eusocial behaviour occurs when individuals reduce their life- eusociality. Several precursors for the origins of eusociality time reproduction to help raise their siblings (Wilson 1971). have been proposed based on comparative analyses among Eusocial colonies comprise two castes: one or a few reproduc- social insect species – primarily the feeding and defense of off- tive individuals and a (mostly) non-reproductive, worker spring within a nest (Andersson 1984). -

Development of Native Bees As Pollinators of Vegetable Seed Crops

Development of native bees as pollinators of vegetable seed crops Dr Katja Hogendoorn The University of Adelaide Project Number: VG08179 VG08179 This report is published by Horticulture Australia Ltd to pass on information concerning horticultural research and development undertaken for the vegetables industry. The research contained in this report was funded by Horticulture Australia Ltd with the financial support of Rijk Zwaan Australia Pty Ltd. All expressions of opinion are not to be regarded as expressing the opinion of Horticulture Australia Ltd or any authority of the Australian Government. The Company and the Australian Government accept no responsibility for any of the opinions or the accuracy of the information contained in this report and readers should rely upon their own enquiries in making decisions concerning their own interests. ISBN 0 7341 2699 9 Published and distributed by: Horticulture Australia Ltd Level 7 179 Elizabeth Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone: (02) 8295 2300 Fax: (02) 8295 2399 © Copyright 2011 Horticulture Australia Limited Final Report: VG08179 Development of native bees as pollinators of vegetable seed crops 1 July 2009 – 9 September 2011 Katja Hogendoorn Mike Keller The University of Adelaide HAL Project VG08179 Development of native bees as pollinators of vegetable seed crops 1 July 2009 – 9 September 2011 Project leader: Katja Hogendoorn The University of Adelaide Waite Campus Adelaide SA 5005 e-mail: [email protected] Phone: 08 – 8303 6555 Fax: 08 – 8303 7109 Other key collaborators: Assoc. Prof. Mike Keller, The University of Adelaide Mr Arie Baelde, Rijk Zwaan Australia Ms Lea Hannah, Rijk Zwaan Australia Ir. Ronald Driessen< Rijk Zwaan This report details the research and extension delivery undertaken in the above project aimed at identification of the native bees that contribute to the pollination of hybrid carrot and leek, and at the development of methods to enhance the presence of these bees on the crops and at enabling their use inside greenhouses. -

Intro Outline

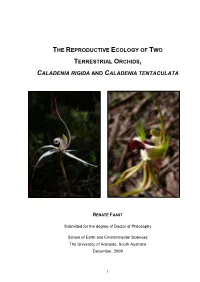

THE REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF TWO TERRESTRIAL ORCHIDS, CALADENIA RIGIDA AND CALADENIA TENTACULATA RENATE FAAST Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Earth and Environmental Sciences The University of Adelaide, South Australia December, 2009 i . DEcLARATION This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution to Renate Faast and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. The author acknowledges that copyright of published works contained within this thesis (as listed below) resides with the copyright holder(s) of those works. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University's digital research repository, the Library catalogue, the Australasian Digital Theses Program (ADTP) and also through web search engines. Published works contained within this thesis: Faast R, Farrington L, Facelli JM, Austin AD (2009) Bees and white spiders: unravelling the pollination' syndrome of C aladenia ri gída (Orchidaceae). Australian Joumal of Botany 57:315-325. Faast R, Facelli JM (2009) Grazrngorchids: impact of florivory on two species of Calademz (Orchidaceae). Australian Journal of Botany 57:361-372. Farrington L, Macgillivray P, Faast R, Austin AD (2009) Evaluating molecular tools for Calad,enia (Orchidaceae) species identification. -

Comparative Methods Offer Powerful Insights Into Social Evolution in Bees Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton

Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton To cite this version: Sarah Kocher, Robert Paxton. Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees. Apidologie, Springer Verlag, 2014, 45 (3), pp.289-305. 10.1007/s13592-014-0268-3. hal- 01234748 HAL Id: hal-01234748 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01234748 Submitted on 27 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Apidologie (2014) 45:289–305 Review article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2014 DOI: 10.1007/s13592-014-0268-3 Comparative methods offer powerful insights into social evolution in bees 1 2 Sarah D. KOCHER , Robert J. PAXTON 1Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA 2Institute for Biology, Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany Received 9 September 2013 – Revised 8 December 2013 – Accepted 2 January 2014 Abstract – Bees are excellent models for studying the evolution of sociality. While most species are solitary, many form social groups. The most complex form of social behavior, eusociality, has arisen independently four times within the bees. -

Molecular Ecology and Social Evolution of the Eastern Carpenter Bee

Molecular ecology and social evolution of the eastern carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica Jessica L. Vickruck, B.Sc., M.Sc. Department of Biological Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Faculty of Mathematics and Science, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © 2017 Abstract Bees are extremely valuable models in both ecology and evolutionary biology. Their link to agriculture and sensitivity to climate change make them an excellent group to examine how anthropogenic disturbance can affect how genes flow through populations. In addition, many bees demonstrate behavioural flexibility, making certain species excellent models with which to study the evolution of social groups. This thesis studies the molecular ecology and social evolution of one such bee, the eastern carpenter bee, Xylocopa virginica. As a generalist native pollinator that nests almost exclusively in milled lumber, anthropogenic disturbance and climate change have the power to drastically alter how genes flow through eastern carpenter bee populations. In addition, X. virginica is facultatively social and is an excellent organism to examine how species evolve from solitary to group living. Across their range of eastern North America, X. virginica appears to be structured into three main subpopulations: a northern group, a western group and a core group. Population genetic analyses suggest that the northern and potentially the western group represent recent range expansions. Climate data also suggest that summer and winter temperatures describe a significant amount of the genetic differentiation seen across their range. Taken together, this suggests that climate warming may have allowed eastern carpenter bees to expand their range northward. Despite nesting predominantly in disturbed areas, eastern carpenter bees have adapted to newly available habitat and appear to be thriving.