“Like a Bird with Broken Wings”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of “Sustainable Livelihood Programme Through Community Mobilization and Establishing Knowledge Resource Centre in Mazar-E-Sharif” Final Report

2013:39 Sida Decentralised Evaluation Sarah Gray Elisabeth Montgomery Evaluation of “Sustainable Livelihood Programme through Community Mobilization and Establishing Knowledge Resource Centre in Mazar-e-Sharif” Final Report Evaluation of “Sustainable Livelihood Programme through Community Mobilization and Establishing Knowledge Resource Centre in Mazar-e-Sharif ” Final Report December 2013 Sarah Gray Elisabeth Montgomery Sida Decentralised Evaluation 2013:39 Sida Authors: Sarah Gray and Elisabeth Montgomery The views and interpretations expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida Decentralised Evaluation 2013:39 Commissioned by Sida - Afghanistan Unit Copyright: Sida and the authors Date of final report: December 2013 Published by Citat 2013 Art. no. Sida61667en urn:nbn:se:sida-61667en This publication can be downloaded from: http://www.sida.se/publications SWEDISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION AGENCY Address: S-105 25 Stockholm, Sweden. Office: Valhallavägen 199, Stockholm Telephone: +46 (0)8-698 50 00. Telefax: +46 (0)8-20 88 64 E-mail: [email protected]. Homepage: http://www.sida.se SIPU International –Final Evaluation Report Acronyms, Abbreviations and Local Terms AMA Association of Microfinance Agencies AREDP Afghanistan Rural Enterprise Development Programme CDC Community Development Council CIA Conflict Impact Assessment EIF Enterprise Incubation Fund DDH District Development Hub FGD Focus Group Discussion GDP Gross Domestic -

UNAMA Civil Military Weekly Report

Issue 7: June 2009 Key Points • Numerous security incidents targeted NGOs in June • Mitigation measures needed for expected flooding in North • Polio eradication campaign in Southern region • Civilian casualty numbers reflect intensification of conflict • Upcoming launch of HAP Mid-Year Review I. Humanitarian Overview development, coordinated by OCHA, ANDMA, and ACBAR. Regional stocktaking is underway, but it is Access already apparent that high-quality sandbags and gabions Attacks on aid workers appeared to increase in June, for the Amu Darya river flood plains are urgently needed. particularly in the north and northeastern regions which Northeastern region: All four provinces in the northeast had previously been considered relatively safe. Most are considered at risk for further flooding (Kunduz and tragically, on 23 June a roadside bomb killed three Baghlan from both rainfall and snowmelt and Takhar and national staff of the NGO Development and Humanitarian Badakhshan from snowmelt). Gabions and sandbags are Services in Afghanistan (DHSA) in Jawzjan province. urgently needed for flood mitigation activities along river Other attacks were reported on NGO vehicles and on UN banks and critical irrigation canals. The Humanitarian offices. A convoy of WFP trucks was stopped in Chast Flood Task Force in Kunduz is carrying out a stocktaking Sharif district in Herat province and later released after exercise and developing a common strategy for mediation efforts. The trend continues to hold that NGO assessments. national staff members are at greatest risk. Particularly in the Northeast, there are concerns about the UNDSS expects that the security situation will continue capacity of local actors to participate in an emergency to deteriorate in the coming months, owing to the response, and external support may be needed. -

Northern Afghanistan – Humanitarian Regional Team Meeting UNICEF

Northern Afghanistan – Humanitarian Regional Team Meeting UNICEF Mazar-e-Sharif on 30 July 2015 Draft Minutes Participants: ACBAR, ACF, ADEO, DAIL, DACAAR, FAO, IOM, Johanniter, NRC, NRDOAW, OCHA, PIN, SCI, SHA, UNHCR, UNICEF, WFP, WHH, and WHO. Apologies from Actionaid and ZOA. Agenda: Welcome and introductions, review of previous action points, UNHCR conflict displacement update, IOM flood update, Cluster updates, pooled funding updates, and humanitarian planning dates. # Agenda Item Issues Action Points 1 Welcome and OCHA welcomed participants and participants introduced themselves. introductions 2 Review of action points Action points addressed by Clusters and IDP Task Force. from previous meeting 3 UNHCR update on UNHCR update: Faryab, Kunduz and Takhar provinces face a new wave of conflict- UNHCR to conflict displacement induced displacement. The rate of new displacement exceeds contingency planning. To follow up with give an example, Takhar province shows a 2015 contingency planning figure of 300 IDP national families, whereas confirmed displacement in July amounts to 706 families. In Kunduz Protection province, fighting in Khanabad district has led to major new displacement. UNHCR has Cluster on alerted the Humanitarian Country Team to this new displacement and is following up on funding for resource mobilization. The regional displacement figures are as follows: new large scale conflict Confirmed conflict displacement in Northern Afghanistan displacement Date: 29 July 2015. Source: UNHCR in northern Province Confirmed conflict IDP families Afghanistan. Badakhshan 885 Baghlan 10 Balkh 143 Faryab 2,033 Jawzjan 66 1 Kunduz 5,840 Samangan 43 Sar-e-Pul 194 Takhar 706 Total 9,920 UNHCR further informed about a forthcoming change in IDP Task Force management, involving a change over from UNHCR to OCHA. -

Nahar Shahe District Raziq

Raziq | Poultry farmer | Kaldar district Nafisa | Food canner | Nahar Shahe district OPERATIONS ACROSS THE NETWORK: AFGHANISTAN Zabor | Honey producer | Marmul district Asifa | Grocer | Nahar Shahe district PROGRESS REPORT OCT 2013-MAR 2014 OPERATIONS ACROSS THE NETWORK: AFGHANISTAN 11 5,289 3,566 2,896 4,321 968JOBS ADDED 670BUSINESSES ADDED O CT 2013-MAR 2014 O CT 2013-MAR 2014 GROWT GROWT H Sep 2013 Mar 2014 22% Sep 2013 Mar 2014 23% H Cumulative jobs Cumulative businesses We put recruitment on hold for six months to focus exclusively on strengthening current members’ businesses. The next six months will see a return to expansion. 14,425 1,542 14,425 670 National six-month Number of new businesses average of new formal supported by HiH in the six businesses* months to March 2014 RECRUITMENT Sep 2013 Mar 2014 PAUSED Hand in Hand business growth versus the national average Cumulative members *This figure captures the average half-yearly number of private companies with limited liability registered between 2004 and 2012 in Afghanistan. Source: World Bank, doingbusiness.org. MEET HABIBA Until recently, Habiba wove carpets on wages for local shops. Then she joined a Hand in Hand Self- Help Group. “I didn’t know about saving before, so I wasn’t able to start my own business,” says the 30-year-old mother of four. Armed with newfound skills and savvy, Habiba devised a plan. First, she researched which designs were most popular in local marketplaces. Next, she made sure to advertise her carpets’ competitive qualities: traditional craftsmanship and natural materials. Finally, she sought out traders to export her carpets to neighboring Uzbekistan. -

OCHA Template

Balkh Province, Kaldar District Floods – Amu Darya Riverbank Erosion Incident Report No. 1 Afghanistan Date: 10 April 2012 This report is produced by OCHA Afghanistan in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It covers the period from 9-12 April 2012. I. HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES • High levels of water in Amu Darya River resulted in riverbank erosion and displacement of 145 families in Kaldar district of Balkh province. • Humanitarian organizations provided emergency shelter, food and non-food assistance. II. Situation Overview High levels of Amu Darya water have eroded riverbanks in Kaldar district of Balkh province. 145 families lost their homes, gardens, agricultural land and livelihoods as a result of the riverbank erosion. A joint assessment was carried out by an inter-agency team consisting of ActionAid, ANDMA, IOM, Save the Children, and WFP. Immediate assistance needs include emergency shelter, non-food items, food, and hygiene kits. On 10 and 12 April, humanitarian organizations provided 145 affected families with three month food rations from WFP and NFI packages from IOM and Save the Children. NFI packages include household items, emergency shelter items, children’s clothes, hygiene kits and quilts. III. Humanitarian Needs and Response Needs: Emergency shelter, non-food items, food, hygiene kits Response: WFP provided food; IOM and Save the Children provided emergency shelter and NFIs. Gaps & Constraints: Governmental plan for resettlement of the displaced families. IV. Coordination Balkh Provincial Disaster Management Committee, Northern Region Emergency Shelter and NFI Cluster, Northern Region Food Security and Agriculture Cluster are being used as coordination platforms. V. Funding In kind and material resources already mobilized. -

THE ANSO REPORT -Not for Copy Or Sale

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 47 01-15 April 2010 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2-5 In BAGHLAN major clashes against NGO presence. ties in KUNAR while the Northern Region 6-10 occurred in Pul-i-Khumri In KANDAHAR the IMF withdrawal from Eastern Region 10-12 and Baghlan-i-Jadid as poppy harvest creates a lull Korangal Valley is expected ANSF/IMF attempted to to improve security there. Southern Region 13-15 in activity. Three BBIEDs reclaim some territory from target NDS HQ in an un- In NANGAHAR clashes Western Region 16-18 AOG in those areas to lim- successful attacks while between empowered tribes- ited success. AOG alignment ANSO Info Page 19 other VBIEDs target the men and the ANP continue with the Pashtun side of a compound of a civilian con- in Sherzad and Khogani land dispute in Hussein Khel tractor and an IMF convoy. while land disputes result in area threatens to polarize An IMF Escalation of violence elsewhere. YOU NEED TO KNOW communities there. Force shooting kills four In NURISTAN road work- In KUNDUZ heavy clashes persons on a local bus and ers are abducted and re- • Heavy fighting in Baghlan, occurred in Chahar Dara escalates tension in the city. Kunduz and Jawzjan leased by AOG while and while AOG focussed their In HERAT and FARAH ANSF proposal to renter • Return of AOG to Marjah response on Kunduz City IEDs result in civilian fatali- Kamdesh district is antici- and significant suicide with IED and rocket strikes. -

OPIATE FLOWS THROUGH NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN and CENTRAL ASIA a Threat Assessment

OPIATE FLOWS THROUGH NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN AND CENTRAL ASIA A Threat Assessment May 2012 OPIATE FLOWS THROUGH NORTHERN AFGHANISTAN AND CENTRAL ASIA: A THREAT ASSESSMENT Acknowledgements This report was prepared by the UNODC Afghan Opiate Trade Project of the Studies and Threat Analysis Section (STAS), Division for Policy Analysis and Public Affairs (DPA), in the framework of UNODC Trends Monitoring and Analysis Programme, with the collaboration of the UNODC Country Office in Afghanistan and the UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia. UNODC is grateful to the national and international institutions which shared their knowledge and data with the report team including, in particular, the Afghan Border Police, the Counter Narcotics Police of Afghanistan, the Ministry of Counter Narcotics of Afghanistan, the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, the Central Asian Regional Information and Coordination Centre, the Customs Service of Tajikistan, the Drug Control Agency of Tajikistan and the State Service on Drug Control of Kyrgyzstan. Acknowledgements also go to the staff of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan and the United Nations Department of Safety and Security in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Report Team Research and report preparation: Hakan Demirbüken (Programme management officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Hayder Mili (Research expert, Afghan Opiate Trade Project, STAS) Yekaterina Spassova (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Hamid Azizi (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Sayed Jalal Pashtoon (National research officer, Afghan Opiate Trade Project) Mapping support: Deniz Mermerci (STAS) Odil Kurbanov (National strategic analyst, UNODC Regional Office for Central Asia) Desktop publishing and mapping support: Suzanne Kunnen (STAS) Kristina Kuttnig (STAS) Supervision: Thibault Le Pichon (Chief, STAS), Sandeep Chawla (Director, DPA) The preparation of this report benefited from the financial contributions of the United States of America, Germany and Turkey. -

People in Need 15 Years in Afghanistan and Beyond

PEOPLE IN NEED 15 YEARS IN AFGHANISTAN PEOPLE IN NEED AND BEYOND How we delivered aid to more than a million 15 YEARS IN AFGHANISTAN Afghan women, men and children. AND BEYOND How we delivered aid to more than a million Afghan women, men and children. INTRODUCTION AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY PROGRAMME ACTIVITIES IN AFGHANISTAN 2001—2016 — WHERE WE OPERATE — WHAT WE DO — EMERGENCY RESPONSE MECHANISM — NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, AGRICULTURE AND LIVELIHOODS — URBAN POVERTY — RURAL REHABILITATION AND DEVELOPMENT — AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION OUR EMPLOYEES FINANCIAL BACKGROUND IN COOPERATION — ALLIANCE 2015 FUTURE PLANS FOR THE AFGHAN COUNTRY PROGRAMME OUR DONORS PEOPLE IN NEED 15 YEARS IN AFGHANISTAN AND BEYOND How we delivered aid to more than a million BADAKHSHAN Afghan women, men and children. JAWZJAN BALKH KUNDUZ INTRODUCTION TAKHAR AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY PROGRAMME ACTIVITIES IN AFGHANISTAN 2001—2016 SAMANGAN BAGHLAN — WHERE WE OPERATE FARYAB — WHAT WE DO PANJSHER SARI PUL — EMERGENCY RESPONSE MECHANISM BADGHIS NURISTAN — NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT, N KUNAR AGRICULTURE AND LIVELIHOODS BAMYAN KAPISA A PARWAN M — URBAN POVERTY H KABUL G — RURAL REHABILITATION AND DEVELOPMENT A L — AGRICULTURAL EDUCATION WARDAK DAY NANGARHAR HERAT GHOR LOGAR OUR EMPLOYEES KUNDI FINANCIAL BACKGROUND ©People in Need, 2017 Editorial staff : Wail Khazal, Daniela Drnková, Veronika Semelková, Emanuela Macková, PAKTYAKHOST IN COOPERATION — ALLIANCE 2015 Lukáš Kotek, Jaroslav Petřík, Petr Štefan, Petr Drbohlav GHAZNI Title photo: Young students in a school supported by PIN in -

Central Region Central Highland Region

Reporting Period: 30 January to 5 February 2014 Donor: OFDA/USAID Submission Date: 5 February 2014 Incidents Update: During the reporting period, two new natural disaster incidents were reported. Central Region Panjsher Province: As per the initial report obtained from ANDMA, on 3 February 2014, four houses were reportedly damaged as a result of heavy snowfall in Shutul district (Janan Joy village). There are no reports of casualty. The roads linking to the district are currently cut off due heavy snowfall. IOM is in close contact with ANDMA and will coordinate assessment and response as soon as the roads are reopened. Parwan Province: On 30 January, as per the reports from ANDMA, due to a mountain slide, three persons died and two were injured. There are no damages to the houses. ANDMA will provide cash assistance to the families of those injured and those who lost their family members. In a separate incident on 4 February, 15 families were reportedly affected as result of heavy snowfall in Kohi Safi, Shinwari and Chaharikar districts of Parwan province. As per initial report from ANDMA and district authorities, the houses of the affected families were damaged. IOM together with ANDMA and partners will initiate an assessment of the affected families on 6 February. IOM will cover the needs for NFIs once the needs of the families are identified. Central Highland Region: Bamyan Province: On 31 January, as a result of mountain slide, a house was completely destroyed in Yakawlang district (Tozajay village) of Bamyan province. IOM together with ANDMA conducted an assessment of the affected family on 1 February. -

MAPPING TRANSBOUNDARY HOTSPOTS for the CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Draft Report Prepared by Stefan Michel)

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals SECOND RANGE STATE MEETING OF THE CMS CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (CAMI) 25 - 28 September 2019, Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia UNEP/CMS/CAMI2/Inf.3 MAPPING TRANSBOUNDARY HOTSPOTS FOR THE CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Draft report prepared by Stefan Michel) Mapping Transboundary Conservation Hotspots for the Central Asian Mammals Initiative Report – Draft 2 for CAMI Range States Representatives and Species Focal Points, revised based on comments by the CMS Secretariat and Stefan Michel Erfurt, 13.09.2019 Disclaimer: The content of this draft report is the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the CMS Secretariat. 1 Table of content Table of content .................................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Background .................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Working approach and methods ................................................................................................ 7 3. Characteristics of the species ..................................................................................................... 9 3.1 General remarks........................................................................................................................ -

Annual Review 2019-20 Healthprom Annual Review 2020

Annual Review 2019-20 HealthProm Annual Review 2020 About Us Who We Are For 35 years HealthProm has been supporting vulnerable Since our foundation, we have gained significant expertise children, women and families in the UK, Eastern Europe, in safe childbirth, the de-institutionalisation of care, palliative Central Asia and Afghanistan. Our unique approach to care for children, support for families of children with providing holistic services encompasses health, social disabilities, and inclusive education. care and education and is driven by our belief that every child should have the best start in life and has the right to What We Offer appropriate care and support. HealthProm’s extensive regional expertise, combined with access to an established network of technical specialists What do we do? in the UK, Europe and Central Asia, enables us to connect We work in partnership with local organisations, parents and professionals and share best practice. We have governments and communities to develop better local an excellent track record of delivering innovative training services for children, women and families. We achieve programmes and participatory forum meetings, organising this through: regional professional conferences and international study visits. • Improving professional practice HealthProm builds local capacity, empowers local people and • Strengthening families and communities supports sustainable reforms. We assist local governments, • Developing innovative services professionals and civil society organisations in professional • Advocating for policy reform learning, strategy development, monitoring and evaluation, designing new projects and preparing funding proposals Where do we work? HealthProm currently works in: Afghanistan Belarus Georgia Russia Tajikistan Ukraine United Kingdom Kyrgyzstan* Moldova* * Projects now completed 2 HealthProm Annual Review 2020 Foreword For over 35 years, HealthProm has been working with local partners and communities in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and Afghanistan to support vulnerable families and their children. -

18 July 2017

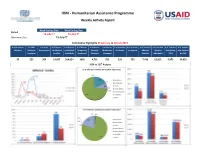

IOM - Humanitarian Assistance Programme Weekly Activity Report Week Starting Date Week Ending Date Period: 12-July-17 18-July-17 Submission Date: 19-July-17 Cumulative Highlights01 January to 18 July 2017 # of Provinces # of ND # of Joint # of Report- # of Report- # of Houses # of Houses # of Houses # of Individu- # of Individu- # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individ- Affected incidents Assessments ed Affected ed Affected Completely Severely Moderately als Deaths als Injured Affected Affected Assisted by uals Assisted Reported Families Individuals Destroyed Damaged Damaged Families Individuals IOM by IOM 33 225 389 14,857 104,024 1618 4,701 753 253 235 7,416 51,912 4,975 34,825 2016 vs 2017 Analysis Weekly Highlights 12-18 July 2017 # of Provinces # of ND # of Joint # of Report- # of Report- # of Houses # of Houses # of Houses # of Individu- # of Individu- # of Verified # of Verified # of Families # of Individ- Affected incidents Assessments ed Affected ed Affected Completely Severely Moderately als Deaths als Injured Affected Affected Assisted by uals Assisted Reported Families Individuals Destroyed Damaged Damaged Families Individuals IOM by IOM 10 16 16 874 6,118 198 98 23 17 21 318 2,226 291 2037 Natural Disasters, Coordination and DRR activity UPDATE: 12-18 July, 2017 Nangarhar: A joint assessment team consisting of IOM, ANDMA, OHW and WFP initiated an as- sessment on 18 July, the assessment results is expected by next week. As a result of wind-storm on 16 July, 141 families were reportedly affected in Chapre- har, Kama, Rodat, Behsood and Surkhrod districts. IOM together with ANDMA, IRC, In as separate incident, 276 families were reported affected by riverbank erosion in IMC and WFP initiated assessment on 18 July.