Shears Ellard Gore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocabulary of Definitions : P

Service bibliothèque Catalogue historique de la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice Source : Monographie de l’Observatoire de Nice / Charles Garnier, 1892. Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur Février 2012 Présentation << On trouve… à l’Ouest … la bibliothèque avec ses six mille deux cents volumes et ses trentes journaux ou recueils périodiques…. >> (Façade principale de la Bibliothèque / Phot. attribuée à Michaud A. – 188? - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) C’est en ces termes qu’Henri Joseph Anastase Perrotin décrivait la bibliothèque de l’Observatoire de Nice en 1899 dans l’introduction du tome 1 des Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice 1. Un catalogue des revues et ouvrages 2 classé par ordre alphabétique d’auteurs et de lieux décrivait le fonds historique de la bibliothèque. 1 Introduction, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. XIV 2 Catalogue de la bibliothèque, Annales de l’Observatoire de Nice publiés sous les auspices du Bureau des longitudes par M. Perrotin. Paris,Gauthier-Villars,1899, Tome 1,p. 1 Le présent document est une version remaniée, complétée et enrichie de ce catalogue. (Bibliothèque, vue de l’intérieur par le photogr. Jean Giletta, 191?. - Marc Heller © Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur) Chaque référence est reproduite à l’identique. Elle est complétée par une notice bibliographique et éventuellement par un lien électronique sur la version numérisée. Les titres et documents non encore identifiés sont signalés en italique. Un index des auteurs et des titres de revues termine le document. -

No. 3 an Independent Miscellany of Astronomy John Hadley's Reflecting

No. 3 An Independent Miscellany of Astronomy 4 February 2019 In 1672, when Isaac Newton read of the enigmatic Monsieur him, that such projects are of little moment till they be put in Cassegrain’s design for a reflecting telescope, he expressed practise.’ Subsequently, the Gregorian design was predom- his opinions in a letter to Henry Oldenburg, Secretary of the inant throughout the eighteenth century, while Newtonian Royal Society. After extensive adverse criticism, the letter telescopes became very popular with the introduction of concludes: ‘You see therefore, that the advantages of this silver-on-glass mirrors in the late 1850s. If Newton could be design are none, but the disadvantages so great and unav- informed that the Cassegrainian design is now incorporated oidable, that I fear it will never be put in practise with good in many instruments, it is probable that he would respond in effect ... I could wish therefore, Mr Cassegrain had tryed a characteristic manner with an acerbic comment. his design before he divulged it. But if, for further satisfaction he please hereafter to try it, I believe the success will inform Bob Marriott _____________________________________________________________________________ John Hadley’s reflecting telescope its thin section parallel with the longitudinal axis of the tele- scope in order to minimise or obviate optical effects, while After the efforts of Gregory, Reive, Newton, Cox, Hooke, and the other end of this brass arm was attached to a sliding Cassegrain from the mid-1660s until around 1704, develop- unit which fitted into wide grooves along the length of a ment of the reflecting telescope remained quiescent until rectangular aperture in the side of the tube. -

Smyth, Dawes, and Lassell

No. 2 An Independent Miscellany of Astronomy 26 October 2018 In Occasional Notes No. 1, my article on John Herschel inc- and I sometimes sense that I might be intruding in his priv- ludes letters written by his daughter Francisca. I also have ate affairs. Nevertheless, these letters were written more in my collections a large number of letters written by William than 150 years ago – a temporal distance sufficient to rem- Rutter Dawes, and letters and documents received by him. ove such impediment. With this in mind, a glimpse into this For the most part these do not concern scientific matters, correspondence is presented here. but instead provide an insight into the social affairs of a The second article in this issue is Part II of Alan Snook’s group of astronomers who remained close friends over a report on his restoration of a fine instrument manufactured period of half a century. When reading these letters I often by Rob and Jim Hysom. have to remind myself that I am holding the paper that Dawes held and wrote upon with the ink from his ink-well, Bob Marriott xxxxxx Smyth, Dawes, and Lassell In the first volume of the Royal Astronomical Soc- iety’s Monthly Notices, published in 1830, William Henry Smyth presented an account of the observ- atory that he had established in Bedford, including a description of his 5.9-inch Tulley refractor. ____________________________________________________________ The object-glass of the telescope is of 8½ feet focal 9 length, with a clear aperture of 5 /10 inches, work- ed by the late Mr. -

The Two Babylons Or the Papal Worship Proved to Be the Worship of Nimrod and His Wife

THE TWO BABYLONS OR THE PAPAL WORSHIP PROVED TO BE THE WORSHIP OF NIMROD AND HIS WIFE. With sixty-one Woodcut Illustrations from NINEVEH, BABYLON, EGYPT, POMPEII, &c. BY THE LATE REV. ALEXANDER HISLOP, OF EAST FREE CHURCH, ARBROATH. Seventh Edition. 1871 LONDON: S. W. PARTRIDGE & CO., 9 PATERNOSTER ROW. TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD JOHN SCOTT, AS A TESTIMONY OF RESPECT FOR HIS TALENTS, AND THE DEEP AND ENLIGHTENED INTEREST TAKEN BY HIM IN THE SUBJECT OF PRIMEVAL ANTIQUITY; AS WELL AS AN EXPRESSION OF GRATITUDE FOR MANY MARKS OF COURTESY AND KINDNESS RECEIVED AT HIS HANDS; This Work IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED BY HIS OBLIGED AND FAITHFUL SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. This Digital Edition has been restored, expanded, reset and the images remastered by the Central Highlands Congregation of God. 20 February, 2021 2 Table of Contents Note By The Editor............................................................................8 Preface to the Second Edition............................................................9 Preface To The Third Edition..........................................................11 Editions Of Works...........................................................................18 THE TWO BABYLONS...................................................................1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................1 CHAPTER I.—Distinctive Character of the Two Systems...............5 CHAPTER II.—Objects of Worship...............................................17 Section I.—Trinity In Unity........................................................17 -

Bulletin Issue 29 Spring 2018 New Series by Paul Haley Begins in This Issue: 19Th Century Observatories 2018 Sha Spring Conference

BULLETIN ISSUE 29 SPRING 2018 NEW SERIES BY PAUL HALEY BEGINS IN THIS ISSUE: 19TH CENTURY OBSERVATORIES 2018 SHA SPRING CONFERENCE The first talk is at 1015 and the Saturday 21st April 2018 The conference registraon is morning session ends at 1215 Instute of Astronomy, between 0930 and 1000 at which for lunch. The lunch break is University of Cambridge me refreshments are available unl 1330. An on-site lunch Madingley Road, Cambridge in the lecture theatre. The will be available (£5.00) BUT CB3 0HA conference starts at 1000 with a MUST BE PRE-ORDERED. There welcome by the SHA Chairman are no nearby eang places. Bob Bower introduces the There is a break for refreshments Aer the break there is the aernoon session at 1330 then from 1530 to 1600 when Tea/ final talk. The aernoon there are two one-hour talks. Coffee and biscuits will be session will end at 5 p.m. and provided. the conference will then close. 10 00 - 1015 10 15 - 1115 1115 - 1215 SHA Chairman Bob Bower Carolyn Kennett and Brian Sheen Kevin Kilburn Welcomes delegates to Ancient Skies and the Megaliths Forgotten Star Atlas the Instute of of Cornwall Astronomy for the SHA 2018 Archeoastronomy in Cornwall The 18th Century unpublished Spring Conference Past and Present Uranographia Britannica by Dr John Bevis 13 30 - 1430 14 30 - 1530 16 00 – 17 00 Nik Szymanek Kenelm England Jonathan Maxwell The Road to Modern Berkshire Astronomers 5000 BC Some lesser known aspects Astrophotography to AD 2018 regarding the evolution of The pioneering days of Some topics on astronomers and refracting telescopes: from early astrophotographers, observations made from Lippershey's spectacle lens to the up to modern times Berkshire since pre-historic Apochromats times until last week An insight into the development of 2 the refracting telescope In this Issue BOOK SALE AT THE 2017 AGM Digital Bulletin The Digital Bulletin provides extra content and links when viewing the 4 Bulletin as a PDF. -

Titles Promote Sustainable Initiatives

Student Research Poster Symposium April 8, 2011 Villanova University Sigma Xi Research Poster Symposium, April 8, 2011 2 Proceedings of the 2011 Student Research Symposium April 8, 2011 Villanova Room Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085 USA Supported by: The Villanova Chapter of Sigma Xi, the Scientific Research Society Sigma Xi Research Poster Symposium, April 8, 2011 This volume is also available electronically on the Sigma Xi chapter’s website, http://www.csc.villanova.edu/~sigmaxi/ Sigma Xi Research Poster Symposium, April 8, 2011 4 Welcome from the Poster Symposium Organizers Welcome to the 2010 Villanova University Sigma Xi’s Student Research Poster Symposium! Sigma Xi is the international honor society for research scientists and engineers. The Villanova chapter of Sigma Xi is proud to sponsor this poster symposium event to recognize and celebrate the research work accomplished by our students, and to give students an opportunity to further develop their skills in communicating those accomplishments. This book contains abstracts of 56 contributed posters. Outstanding posters will be recognized in the form of poster awards. Many thanks to all students who contributed to this symposium. We gratefully acknowledge the dedicated poster judges who committed to evaluating the research posters and providing written feedback at the end of the symposium. Special thanks for their time and commitment to promoting research at Villanova University! Congratulations to all! Mirela Damian Sigma Xi Chapter President Anil Bamezai Sigma Xi Chapter President-Elect Sridhar Santhanam Sigma Xi Chapter Secretary-Treasurer Sigma Xi Research Poster Symposium, April 8, 2011 Table of Contents Astronomy and Astrophysics (5) Ultraviolet Spectral Synthesis of HgMn Stars. -

Vol. 9 No. 2 Summer, 1980 the STAR of BETHLEHEM RECONSIDERED: a THEOLOGICAL APPROACH Carl J

In This Issue THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM RECONS1DERED: A THEOLOG ICAL APPROACH Carl J. Wenning 2 THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM RECONS IDERED: AN HISTORICAL APPROACH .John Mosley and Ernest L. Ma rlin 6 TH E HEAVENS AND A CONSC IOUS EX PER IENCE OF tMORTA LI TY . Georgia Hooks Shurr 11 THE CANALS OF MARS, A RETROSPECTIVE David H. DcVorkin, cesc and Michael Mendillo 12 FEATURES: Letters and Announcements 3 What's New James Brown 9 Focus on Educa tion Jeanne Bis hop 10 Crea tive Corner (How 10 Assemble Space Stillion- Island Onc" by Brian Sullivan) Herb Schwartz' 22 Jane's Comer . • . Jane P. Geohcgan 27 Vol. 9 No. 2 Summer, 1980 THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM RECONSIDERED: A THEOLOGICAL APPROACH Carl J. Wenning 1.S. U. Planetarium Illinois State University Normal, IL 61761 Each and every Christmas season the public hears public if we don't take into account other considerations? from the planetarium community how the Star of It is my firm belief that to truly solve the Christmas star Bethlehem mystery has been solved. As a solution the mystery we must call in someone who is both an famous triple conjunction is proffered. The triple astronomer and a theologian. Now I do not purport to be conjunction occurred in what appears to be the an astronomer, much less a theologian. However I am appr~priate ti me frame, fits many factors, and is sufficiently well versed in biblical studies to ~uggest plausible. In fact, a whole plethora of ideas give support several alternatives to the triple conjunction which simply to the triple conjunction as being THE answer. -

Explorethe Impact That Killed the Dinosaursp. 26

EXPLORE the impact that killed the dinosaurs p. 26 DECEMBER 2016 The world’s best-selling astronomy magazine Understanding cannibal star systems p. 20 How moon dust will put a ring around Mars p. 46 Discover colorful star clusters p. 32 www.Astronomy.com AND MORE BONUS Vol. 44 Astronomy on Tap becomes a hit p. 58 ONLINE • CONTENT Issue 12 Meet the master of stellar vistas p. 52 CODE p. 3 iOptron’s new mount tested p. 62 ÛiÃÌÊÊÞÕÀÊiÞiÌ°°° ...and share the dividends for a lifetime. Tele Vue APO refractors earn a high yield of happy owners. 35 years of hand-building scopes with care and dedication is why we see comments like: “Thanks to all at Tele Vue for such wonderful products.” The care that goes into building every Tele Vue telescope is evident from the first time you focus an image. What goes unseen are the hours of work that led to that moment. Hand-fitted rack & pinion focusers must withstand 10lb. deflection testing along their travel, yet operate buttery-smooth, without gear lash or image TV-60 shift. Optics are fitted, spaced, and aligned using proprietary techniques to form breathtaking low-power views, spectacular high-power planetary performance, or stunning wide-field images. When you purchase a TV-76 Tele Vue telescope you’re not so much buying a telescope as acquiring a lifetime observing companion. Comments from recent warranty cards UÊ/6Èä®ÊºÊV>ÌÊÌ >ÊÞÕÊiÕ} ÊvÀÊ«ÀÛ`}ÊiÊÜÌ ÊÃÕV ʵÕ>ÌÞtÊ/ ÃÊÃV«iÊÜÊ}ÛiÊiÊ>Êlifetime TV-85 of observing happiness.” —M.E.,Canada U/6ÇȮʺ½ÛiÊÜ>Ìi`Ê>Ê/6ÊÃV«iÊvÀÊ{äÊÞi>ÀðÊ>ÞtÊ`]ʽÊÛiÀÜ ii`tÊLove, Love, Love Ìtt»p °°]" U/6nx®ÊºPerfect form, perfect function, perfectÊÌiiÃV«i]Ê>`ÊÊ``½ÌÊ >ÛiÊÌÊÜ>ÌÊxÊÞi>ÀÃÊÌÊ}iÌÊÌt»p,° °]/8 U/6nx®Êº/ >ÊÞÕÊvÀÊ>}ÊÃÕV Êbeautiful equipment available. -

The Corran Herald Issue 47, 2014

COMPILED AND PUBLISHED BY BALLYMOTE HERITAGE GROUP CELEBRATING 30 YEARS 1984-2014 ISSUE NO.47 2014/2015 PRICE €8.00 The Corran Herald Annual Publication of Ballymote Heritage Group Compiled and Published by Ballymote Heritage Group Editor: Stephen Flanagan Design, Typesetting and Printing: Orbicon Print, Collooney Cover Design and Artwork: Brenda Friel Issue No 47 2014/2015 ––––––––––––––– The Corran Herald wishes to sincerely thank all those who have written articles or contributed photographs or other material for this issue Ballymote 25th Annual Heritage Weekend Thursday 31st July The Teagasc Centre, to (Right over railway bridge on Tubbercurry Road) Monday 4th August 2014 Ballymote, Co. Sligo Organised by Ballymote Heritage Group - Celebrating 30 Years (1984 - 2014) Thursday 31st Sunday 3rd Classic Film at 3 pm. Afternoon Tea at Temple The Art Deco Theatre & Cinema House with Classical & The Sound Of Music Baroque Music 7:30pm Tickets €12.50 Admission, Adults €6,Children €3, (Accompanied children free) Tickets from Tighe’s Shop, Ballymote must be purchased in advance from Tighe’s Shop, st Ballymote. Remaining tickets Friday 1 available on opening night 8.30pm. Official Opening 8.30 pm. Lecture: Sligo’s Hidden Mary Kenny, Author & Journalist Bridges Gary Salter, Conservation Lecture: Poets and Priests of Ireland Engineer Senior inWorld War 1 Executive Engineer, Mary Kenny, Author & Journalist Sligo County Council Saturday 2nd Monday 4th 9 am. Outing: Derek Hill 9 am. Outing: Westport House & House and Glebe Gallery, guided walking tour of Churchill, Co.Donegal, historic town and Raphoe Heritage Town 8.30 pm. Lecture: Family Names in Guide: Martin Timoney, BA FRSAI the Place-names of Sligo MIAI Research Archaeologist & Author Dr. -

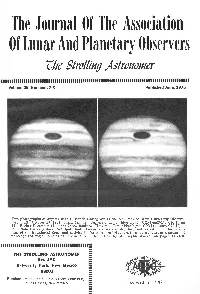

The Journal of the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers Rite Strolli11g Astro11omer

The Journal Of The Association Of Lunar And Planetary Observers rite Strolli11g Astro11omer 1111111 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Volume 25, Numbers 7-8 Published June, 1975 Two photographs of Jupiter with a 12-inch Cassegrain at the New Mexico State University Observa tory. Left: October 23, 1964; 8hrs., 58mins., Universal Time; blue light; CM(I)=251°, CM(II)= 17° . Right: December 12, 1965; 7hrs., 46mins., Universal Time; blue light; CM(I)=182° , CM(II)= 22° . Note the very dark Red Spot, South Temperate Zone ovals, the great variation in the bright ness of the Equatorial Zone, and activity in far northern belts. Are these events part of a pattern of unrecognized major zenological disturbances? See article by Mr. Wynn Wacker on pages 145-150. 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111:: THE STROLLING ASTRONOMER - Box lAZ University Park, New Mexico 88003 - Residence telephone 522-4213 (Area Code 505) - in Las Cruces, New Mexico - Founded In 1947 IN THIS ISSUE OBSERVING OLYMPUS MONS IN 1975, by John E. Westfall -------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 129 MARS 1973-74 APPARITION- ALPO REPORT I, by Robert B. Rhoads and Virginia W. Capen ------------------------------ pg. 130 A PROPOSED ASTROGEOGRAPHICAL SECTION, by James Powell ---------------------------------------------------------------------·---------- pg. 138 JUPITER IN 1972: ROTATION PERIODS, by Phillip W. Budine ---------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Astrophysics

Publications of the Astronomical Institute rais-mf—ii«o of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences Publication No. 70 EUROPEAN REGIONAL ASTRONOMY MEETING OF THE IA U Praha, Czechoslovakia August 24-29, 1987 ASTROPHYSICS Edited by PETR HARMANEC Proceedings, Vol. 1987 Publications of the Astronomical Institute of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences Publication No. 70 EUROPEAN REGIONAL ASTRONOMY MEETING OF THE I A U 10 Praha, Czechoslovakia August 24-29, 1987 ASTROPHYSICS Edited by PETR HARMANEC Proceedings, Vol. 5 1 987 CHIEF EDITOR OF THE PROCEEDINGS: LUBOS PEREK Astronomical Institute of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences 251 65 Ondrejov, Czechoslovakia TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface HI Invited discourse 3.-C. Pecker: Fran Tycho Brahe to Prague 1987: The Ever Changing Universe 3 lorlishdp on rapid variability of single, binary and Multiple stars A. Baglln: Time Scales and Physical Processes Involved (Review Paper) 13 Part 1 : Early-type stars P. Koubsfty: Evidence of Rapid Variability in Early-Type Stars (Review Paper) 25 NSV. Filtertdn, D.B. Gies, C.T. Bolton: The Incidence cf Absorption Line Profile Variability Among 33 the 0 Stars (Contributed Paper) R.K. Prinja, I.D. Howarth: Variability In the Stellar Wind of 68 Cygni - Not "Shells" or "Puffs", 39 but Streams (Contributed Paper) H. Hubert, B. Dagostlnoz, A.M. Hubert, M. Floquet: Short-Time Scale Variability In Some Be Stars 45 (Contributed Paper) G. talker, S. Yang, C. McDowall, G. Fahlman: Analysis of Nonradial Oscillations of Rapidly Rotating 49 Delta Scuti Stars (Contributed Paper) C. Sterken: The Variability of the Runaway Star S3 Arietis (Contributed Paper) S3 C. Blanco, A. -

Astronomy Magazine 2020 Index

Astronomy Magazine 2020 Index SUBJECT A AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers), Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 Abell 21 (Medusa Nebula), 2:56, 59 Abell 85 (galaxy), 4:11 Abell 2384 (galaxy cluster), 9:12 Abell 3574 (galaxy cluster), 6:73 active galactic nuclei (AGNs). See black holes Aerojet Rocketdyne, 9:7 airglow, 6:73 al-Amal spaceprobe, 11:9 Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri) (star), binocular observation of, 1:62 Alnasl (Gamma Sagittarii) (optical double star), 8:68 Alpha Canum Venaticorum (Cor Caroli) (star), 4:66 Alpha Centauri A (star), 7:34–35 Alpha Centauri B (star), 7:34–35 Alpha Centauri (star system), 7:34 Alpha Orionis. See Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis) Alpha Scorpii (Antares) (star), 7:68, 10:11 Alpha Tauri (Aldebaran) (star), binocular observation of, 1:62 amateur astronomy AAVSO Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 beginner’s guides, 3:66, 12:58 brown dwarfs discovered by citizen scientists, 12:13 discovery and observation of exoplanets, 6:54–57 mindful observation, 11:14 Planetary Society awards, 5:13 satellite tracking, 2:62 women in astronomy clubs, 8:66, 9:64 Amateur Telescope Makers of Boston (ATMoB), 8:66 American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) binocular observations of, 12:60 consumption of dwarf galaxies, 2:11 images of, 3:72, 6:31 satellite galaxies, 11:62 Antares (Alpha Scorpii) (star), 7:68, 10:11 Antennae galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), 3:28 Apollo missions commemorative postage stamps, 11:54–55 extravehicular activity