Smyth, Dawes, and Lassell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 3 an Independent Miscellany of Astronomy John Hadley's Reflecting

No. 3 An Independent Miscellany of Astronomy 4 February 2019 In 1672, when Isaac Newton read of the enigmatic Monsieur him, that such projects are of little moment till they be put in Cassegrain’s design for a reflecting telescope, he expressed practise.’ Subsequently, the Gregorian design was predom- his opinions in a letter to Henry Oldenburg, Secretary of the inant throughout the eighteenth century, while Newtonian Royal Society. After extensive adverse criticism, the letter telescopes became very popular with the introduction of concludes: ‘You see therefore, that the advantages of this silver-on-glass mirrors in the late 1850s. If Newton could be design are none, but the disadvantages so great and unav- informed that the Cassegrainian design is now incorporated oidable, that I fear it will never be put in practise with good in many instruments, it is probable that he would respond in effect ... I could wish therefore, Mr Cassegrain had tryed a characteristic manner with an acerbic comment. his design before he divulged it. But if, for further satisfaction he please hereafter to try it, I believe the success will inform Bob Marriott _____________________________________________________________________________ John Hadley’s reflecting telescope its thin section parallel with the longitudinal axis of the tele- scope in order to minimise or obviate optical effects, while After the efforts of Gregory, Reive, Newton, Cox, Hooke, and the other end of this brass arm was attached to a sliding Cassegrain from the mid-1660s until around 1704, develop- unit which fitted into wide grooves along the length of a ment of the reflecting telescope remained quiescent until rectangular aperture in the side of the tube. -

Vol. 9 No. 2 Summer, 1980 the STAR of BETHLEHEM RECONSIDERED: a THEOLOGICAL APPROACH Carl J

In This Issue THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM RECONS1DERED: A THEOLOG ICAL APPROACH Carl J. Wenning 2 THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM RECONS IDERED: AN HISTORICAL APPROACH .John Mosley and Ernest L. Ma rlin 6 TH E HEAVENS AND A CONSC IOUS EX PER IENCE OF tMORTA LI TY . Georgia Hooks Shurr 11 THE CANALS OF MARS, A RETROSPECTIVE David H. DcVorkin, cesc and Michael Mendillo 12 FEATURES: Letters and Announcements 3 What's New James Brown 9 Focus on Educa tion Jeanne Bis hop 10 Crea tive Corner (How 10 Assemble Space Stillion- Island Onc" by Brian Sullivan) Herb Schwartz' 22 Jane's Comer . • . Jane P. Geohcgan 27 Vol. 9 No. 2 Summer, 1980 THE STAR OF BETHLEHEM RECONSIDERED: A THEOLOGICAL APPROACH Carl J. Wenning 1.S. U. Planetarium Illinois State University Normal, IL 61761 Each and every Christmas season the public hears public if we don't take into account other considerations? from the planetarium community how the Star of It is my firm belief that to truly solve the Christmas star Bethlehem mystery has been solved. As a solution the mystery we must call in someone who is both an famous triple conjunction is proffered. The triple astronomer and a theologian. Now I do not purport to be conjunction occurred in what appears to be the an astronomer, much less a theologian. However I am appr~priate ti me frame, fits many factors, and is sufficiently well versed in biblical studies to ~uggest plausible. In fact, a whole plethora of ideas give support several alternatives to the triple conjunction which simply to the triple conjunction as being THE answer. -

Shears Ellard Gore

John Ellard Gore: ‘of immensity and minuteness’1 Jeremy Shears John Ellard Gore FRAS, MRIA (1845−1910) was an Irish amateur astronomer and prolific author of popular astronomy books. His main observational interest was variable stars, of which he discovered several, and he served as the first Director of the BAA Variable Star Section. He was also interested in binary stars, leading him to calculate the orbital elements of many such systems. He demonstrated that the companion of Sirius, thought by many to be a dark body, was in fact self-luminous. In doing so he provided the first indication of the enormous density of what later became known as white dwarfs. Introduction were descended from Sir Paul Gore (1567−1629), who was born in London and went to Ireland in John Ellard Gore (1845−1910; Figure 1) was an 1602 as a commander of a troop of horse. In 1615 Irish amateur astronomer and prolific author of he became MP for Ballyshannon in County Don- popular astronomy books. His main observa- egal10 and in 1622 was created Baronet of tional interest was variable stars. He was an Magherabegg, also in Donegal.11 The Gore fam- original member of the British Astronomical ily seat was Manor Gore in Donegal. John Ellard Association in 1890 and shortly after was ap- Gore’s great grandfather, Arthur Saunders Gore pointed as the first Director of the Associa- (1734−1809), was the Second Earl of Arran and tion’s Variable Star Section (BAA VSS), which the Arran Islands. is the world’s longest established organisation John Ellard Gore had three brothers12 and a for the systematic observation of variable stars. -

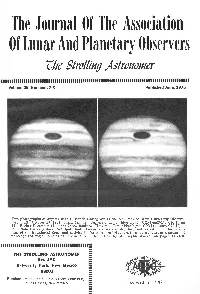

The Journal of the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers Rite Strolli11g Astro11omer

The Journal Of The Association Of Lunar And Planetary Observers rite Strolli11g Astro11omer 1111111 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 Volume 25, Numbers 7-8 Published June, 1975 Two photographs of Jupiter with a 12-inch Cassegrain at the New Mexico State University Observa tory. Left: October 23, 1964; 8hrs., 58mins., Universal Time; blue light; CM(I)=251°, CM(II)= 17° . Right: December 12, 1965; 7hrs., 46mins., Universal Time; blue light; CM(I)=182° , CM(II)= 22° . Note the very dark Red Spot, South Temperate Zone ovals, the great variation in the bright ness of the Equatorial Zone, and activity in far northern belts. Are these events part of a pattern of unrecognized major zenological disturbances? See article by Mr. Wynn Wacker on pages 145-150. 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111:: THE STROLLING ASTRONOMER - Box lAZ University Park, New Mexico 88003 - Residence telephone 522-4213 (Area Code 505) - in Las Cruces, New Mexico - Founded In 1947 IN THIS ISSUE OBSERVING OLYMPUS MONS IN 1975, by John E. Westfall -------------------------------------------------------------------------- pg. 129 MARS 1973-74 APPARITION- ALPO REPORT I, by Robert B. Rhoads and Virginia W. Capen ------------------------------ pg. 130 A PROPOSED ASTROGEOGRAPHICAL SECTION, by James Powell ---------------------------------------------------------------------·---------- pg. 138 JUPITER IN 1972: ROTATION PERIODS, by Phillip W. Budine ---------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Feast of Astro-History at Greenwich

Society for the History of Astronomy Volume 7, no. 1, January 2015. Editor: David Sellers FEAST OF ASTRO-HISTORY Stuart Clark, widely read astronomy journalist and author of AT GREENWICH the highly successful Sky's Dark Labyrinth Trilogy, will be talking about the subject of his acclaimed biography The Sun Kings— Richard Carrington and the 1859 Solar Flare. The US astrophysicist and historian of astronomy, Prof. Jay Pasachoff, fresh back from Stuart Clark observing the March 2015 solar (image-courtesy eclipse, will take us back to Simon Wallace*) sixteenth century astronomy as he speaks about the seminal discoveries of Galileo Galilei and Simon Marius, in relation to the Moon and Jupiter's satellites. Stellar line-up for joint Jay is the Field SHA–BAA Spring Conference 28 March Memorial Professor of The 2015 Spring Conference of the Society for the Astronomy at Williams College, Massachusetts, History of Astronomy will take the form of a joint Prof.Jay Pasachoff event with the History Section of the British and is responsible for a (image: Williams College) Astronomical Association. It will be on Saturday 28th number of general March 2015 at the National Maritime Museum, astronomy textbooks, Greenwich, and promises to be a memorable event. which have become popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Giving the Alan Cox/David Dewhirst Memorial Lecture Anthony Kinder, former Directory of the BAA will be William Sheehan, History Section, will outline the major study that he renowned US author of many has been undertaking into the historical membership of books on the history of the BAA and the SHA. -

Telescopes and the Popularization of Astronomy in the Twentieth Century Gary Leonard Cameron Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2010 Public skies: telescopes and the popularization of astronomy in the twentieth century Gary Leonard Cameron Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Cameron, Gary Leonard, "Public skies: telescopes and the popularization of astronomy in the twentieth century" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 11795. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/11795 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Public skies: telescopes and the popularization of astronomy in the twentieth century by Gary Leonard Cameron A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: History of Science and Technology Program of study committee: Amy S. Bix, Major Professor James T. Andrews David B. Wilson John Monroe Steven Kawaler Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2010 Copyright © Gary Leonard Cameron, 2010. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Forward and Acknowledgements iv Dissertation Abstract v Chapter I: Introduction 1 1. General introduction 1 2. Research methodology 8 3. Historiography 9 4. Popularization – definitions 16 5. What is an amateur astronomer? 19 6. Technical definitions – telescope types 26 7. Comparison with other science & technology related hobbies 33 Chapter II: Perfecting ‘A Sharper Image’: the Manufacture and Marketing of Telescopes to the Early 20th Century 39 1. -

The History of Stellar Photometry

The History of Stellar Photometry Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 25 Sep 2021 at 17:46:06, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0252921100007326 George M. Minchin, FRS (1845-1914) William H.S. Monck (1839-1915) George F. Fitzgerald, FRS (1851-1901) Stephen M. Dixon (1866-1940) Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 25 Sep 2021 at 17:46:06, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0252921100007326 at^sa^^ii^^^^^-^^^jijfiigjj Biographical and Historical Notes on the Pioneers of Photometry in Ireland The Editors Introduction As the circumstances of the early electrical measurements of starlight in Ireland are not widely known we wish to take this opportunity to set down the facts, as far as they are known to us. Corrections or new information will be welcomed. The observations made in Dublin in 1892 were the result of a collaboration be tween four graduates of Trinity College: George M. Minchin, William H.S. Monck, Stephen M. Dixon and George F. Fitzgerald. The observations in 1895 were made at Daramona Observatory, Co. Westmeath with a 24-inch reflector by Minchin, Fitzger ald and the owner of the telescope, William E. Wilson. In 1875 Minchin was appointed Professor of Applied Mechanics at the Royal Indian Engineering College at Coopers Hill, near Staines in London. In 1877 he started a long series of investigations of photoelectricity using a small optical laboratory at Coopers Hill and the laboratories of University College London. -

Convert Finding Aid To

The Herschel Family: An Inventory of Their Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Herschel Family Title: Herschel Family Papers Dates: 1721-1951 (bulk 1810-1871) Extent: 44 document boxes, 2 oversize boxes, 1 custom box (20.48 linear feet), 17 oversize folders (osf), and 2 oversize framed items Abstract: The Herschel Family Papers largely represent the life and work of Sir John F. W. Herschel (1792-1871), the English mathematician, astronomer, chemist, and experimental photographer/inventor. Also present are manuscripts and correspondence by and about John's father Sir William Herschel (1738-1822), discoverer of the planet Uranus and stellar astronomy pioneer; John's aunt, the noted astronomer Caroline Lucretia Herschel (1750-1848); and many other Herschel family members, scientific colleagues, and friends. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-1931 Language: English, French, German, Italian, and Latin Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the Center for History of Physics, American Institute of Physics, which provided funds to support the processing and cataloging of this collection. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases, 1960-1980 (R56, R56a, R56b, R529, R612, R2319, R4548, R4591, R4957, R5077, R8449, R8712, and R11999) Processed by: Micah Erwin and Joan Sibley, 2011 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Herschel Family Manuscript Collection MS-1931 Biographical Sketches Sir William Herschel, 1738-1822 The fourth of ten children, Sir William Herschel was born in Hanover, Germany, on 15 November 1738 to Isaac Herschel (1707–1767) and his wife Anna Ilse Moritzen. He was baptized as Friedrich Wilhelm. Herschel's father was an oboist in the Hanoverian Foot Guards and although not wealthy, he encouraged his sons to pursue science and philosophy. -

John Ellard Gore: of Immensity and Minuteness (1)

1 John Ellard Gore: of immensity and minuteness (1) Jeremy Shears Abstract John Ellard Gore FRAS, MRIA (1845-1910) was an Irish amateur astronomer and prolific author of popular astronomy books. His main observational interest was variable stars, of which he discovered several, and he served as the first Director of the BAA Variable Star Section. He was also interested in binary stars, leading him to calculate orbital elements of many such systems. He demonstrated that the companion of Sirius, thought by many to be a dark body, was in fact self luminous. In doing so he provided the first indication of the immense density of what later became known as white dwarfs. Introduction John Ellard Gore (1845-1910; Figure 1) was an Irish amateur astronomer and prolific author of popular astronomy books. His main observational interest was variable stars. He was a founding member of the British Astronomical Association in 1890 and shortly after was appointed as the first Director of the Association‘s Variable Star Section (BAA VSS), which is the world‘s longest established organisation for the systematic observation of variable stars. Gore was a civil engineer by profession and served in India for 11 years before retiring to pursue his astronomical interests. Apart from variable stars, Gore was also intensely interested in binary stars, leading him to calculate the orbital elements of many such systems. In later years, most of Gore‘s attention was focussed on theoretical astronomy. He was the first person to estimate the density of a white dwarf (Sirius B), although, as we shall see, he rejected his result as he simply could not accept that matter of such high density could exist. -

Feast of Astro-History at Greenwich

Society for the History of Astronomy Volume 7, no. 1, January 2015. Editor: David Sellers FEAST OF ASTRO-HISTORY Stuart Clark, widely read AT GREENWICH astronomy journalist and author of the highly successful Sky's Dark Labyrinth Trilogy, will be talking about the subject of his acclaimed biography The Sun Kings— Richard Carrington and the 1859 Solar Flare. The US astrophysicist and historian of astronomy, Prof. Jay Pasachoff, fresh back from Stuart Clark observing the March 2015 solar (image-courtesy eclipse, will take us back to Simon Wallace*) sixteenth century astronomy as he speaks about the seminal discoveries of Galileo Galilei and Simon Marius, in relation to the Moon and Jupiter's satellites. Stellar line-up for joint Jay is the Field SHA–BAA Spring Conference 28 March Memorial Professor of The 2015 Spring Conference of the Society for the Astronomy at Williams College, Massachusetts, History of Astronomy will take the form of a joint Prof.Jay Pasachoff event with the History Section of the British and is responsible for a Astronomical Association. It will be on Saturday 28th (image: Williams College) number of general March 2015 at the National Maritime Museum, astronomy textbooks, Greenwich, and promises to be a memorable event. which have become popular on both sides of the Atlantic. Giving the Alan Cox/David Dewhirst Memorial Lecture Anthony Kinder, former Directory of the BAA will be William Sheehan, History Section, will outline the major study that he renowned US author of many has been undertaking into the historical membership of books on the history of the BAA and the SHA. -

The Complete CD Guide to the Universe Practical Astronomy

P1: PAB/SPH P2: XXX SVNY329-Harshaw SVNY329-FM.tex December 14, 2006 10:6 Patrick Moore’s Practical Astronomy Series i P1: PAB/SPH P2: XXX SVNY329-Harshaw SVNY329-FM.tex December 14, 2006 10:6 The Complete CD Guide to the Universe Practical Astronomy Richard Harshaw With 31 Figures iii P1: PAB/SPH P2: XXX SVNY329-Harshaw SVNY329-FM.tex December 14, 2006 10:6 Richard Harshaw Stardeck Observatory, Kansas City, MO, USA 1817 NE 83rd Street Kansas City 64118 Email, personal: [email protected] British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2006940068 Patrick Moore’s Practical Astronomy Series ISBN-10: 0-387-46893-5 e-ISBN-10: 0-387-46895-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-387-46893-8 e-ISBN-13: 978-0-387-46895-2 Printed on acid-free paper C Springer-Verlag London Limited 2007 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. The use of registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

History of Astronomy in Australia: Big-Impact Astronomy from World War II Until the Lunar Landing (1945–1969)

galaxies Article History of Astronomy in Australia: Big-Impact Astronomy from World War II until the Lunar Landing (1945–1969) Alister W. Graham 1,* , Katherine H. Kenyon 1,†, Lochlan J. Bull 2,‡ , Visura C. Lokuge Don 3,§ and Kazuki Kuhlmann 4,k 1 Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Hawthorn, VIC 3122, Australia 2 Horsham College, PO Box 508, Horsham, VIC 3402, Australia 3 Glen Waverley Secondary College, 39 O’Sullivan Rd, Glen Waverley, VIC 3150, Australia 4 Marcellin College, 160 Bulleen Road, Bulleen, VIC 3105, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] † Current address: Central Clinical School, The Alfred Centre, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC 3004, Australia. ‡ Current address: Department of Economics, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Melbourne, Carlton, VIC 3053, Australia. § Current address: Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Monash University, Clayton, VIC 3800, Australia. k Current address: School of Engineering, RMIT, GPO Box 2476, Melbourne, VIC 3001, Australia. Abstract: Radio astronomy commenced in earnest after World War II, with Australia keenly en- gaged through the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. At this juncture, Australia’s Citation: Graham, A.W.; Kenyon, K.H.; Bull, L.J.; Lokuge Don, V.C.; Commonwealth Solar Observatory expanded its portfolio from primarily studying solar phenomena Kuhlmann, K. History of Astronomy to conducting stellar and extragalactic research. Subsequently, in the 1950s and 1960s, astronomy in Australia: Big-Impact Astronomy gradually became taught and researched in Australian universities. However, most scientific publica- from World War II until the Lunar tions from this era of growth and discovery have no country of affiliation in their header information, Landing (1945–1969).