Outlier Kinase Expression by RNA Sequencing As Targets for Precision Therapy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Number of Genes

Table S1. The numbers of KD genes in each KD time The number The number The number The number Cell lines of genes of genes of genes of genes (96h) (120h) (144h) PC3 3980 3822 128 1725 A549 3724 3724 0 0 MCF7 3688 3471 0 1837 HT29 3665 3665 0 0 A375 3826 3826 0 0 HA1E 3801 3801 0 0 VCAP 4134 34 4121 0 HCC515 3522 3522 0 0 Table S2. The predicted results in the PC3 cell line on the LINCS II data id target rank A07563059 ADRB2 48 A12896037 ADRA2C 91 A13021932 YES1 77 PPM1B;PPP1CC;PPP2CA; A13254067 584;1326;297;171;3335 PTPN1;PPP2R5A A16347691 GMNN 2219 PIK3CB;MTOR;PIK3CA;PIK A28467416 18;10;9;13;8 3CG;PIK3CD A28545468 EHMT2;MAOB 14;67 A29520968 HSPB1 1770 A48881734 EZH2 1596 A52922642 CACNA1C 201 A64553394 ADRB2 155 A65730376 DOT1L 3764 A82035391 JUN 378 A82156122 DPP4 771 HRH1;HTR2C;CHRM3;CH A82772293 2756;2354;2808;2367 RM1 A86248581 CDA 1785 A92800748 TEK 459 A93093700 LMNA 1399 K00152668 RARB 105 K01577834 ADORA2A 525 K01674964 HRH1;BLM 31;1314 K02314383 AR 132 K03194791 PDE4D 30 K03390685 MAP2K1 77 K06762493 GMNN;APEX1 1523;2360 K07106112 ERBB4;ERBB2;EGFR 497;60;23 K07310275 AKT1;MTOR;PIK3CA 13;12;1 K07753030 RGS4;BLM 3736;3080 K08109215 BRD2;BRD3;BRD4 1413;2786;3 K08248804 XIAP 88 K08586861 TBXA2R;MBNL1 297;3428 K08832567 GMNN;CA12 2544;50 LMNA;NFKB1;APEX1;EH K08976401 1322;341;3206;123 MT2 K09372874 IMPDH2 232 K09711437 PLA2G2A 59 K10859802 GPR119 214 K11267252 RET;ALK 395;760 K12609457 LMNA 907 K13094524 BRD4 7 K13662825 CDK4;CDK9;CDK5;CDK1 34;58;13;18 K14704277 LMNA;BLM 1697;1238 K14870255 AXL 1696 K15170068 MAN2B1 1756 K15179879 -

Novel Functions of Death-Associated Protein Kinases Through Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-Related Signals

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Novel Functions of Death-Associated Protein Kinases through Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase-Related Signals Mohamed Elbadawy 1,2,† , Tatsuya Usui 1,*,†, Hideyuki Yamawaki 3 and Kazuaki Sasaki 1 1 Laboratory of Veterinary Pharmacology, Department of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture, Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, 3-5-8 Saiwai-cho, Fuchu, Tokyo 183-8509, Japan; [email protected] (M.E.); [email protected] (K.S.) 2 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Benha University, Moshtohor, Elqaliobiya, Toukh 13736, Egypt 3 Laboratory of Veterinary Pharmacology, School of Veterinary Medicine, Kitasato University, Towada, Aomori 034-8628, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +81-42-367-5769 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 13 September 2018; Accepted: 1 October 2018; Published: 4 October 2018 Abstract: Death associated protein kinase (DAPK) is a calcium/calmodulin-regulated serine/threonine kinase; its main function is to regulate cell death. DAPK family proteins consist of DAPK1, DAPK2, DAPK3, DAPK-related apoptosis-inducing protein kinases (DRAK)-1 and DRAK-2. In this review, we discuss the roles and regulatory mechanisms of DAPK family members and their relevance to diseases. Furthermore, a special focus is given to several reports describing cross-talks between DAPKs and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) family members in various pathologies. We also discuss small molecule inhibitors of DAPKs and their potential as therapeutic targets against human diseases. Keywords: MAPK; DAPK; ERK; p38; JNK 1. Introduction: DAPKs, MAPKs Death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) family proteins are closely related, Ca2+/calmodulin (CaM)-regulated serine/threonine kinases, whose members not only possess significant homology in their catalytic domains but also share cell death-associated functions [1,2]. -

Novel Methylation Patterns Predict Outcome in Uveal Melanoma

Article Novel Methylation Patterns Predict Outcome in Uveal Melanoma Sarah Tadhg Ferrier 1 and Julia Valdemarin Burnier 1,2,3,* 1 Cancer Research Program, Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada, H4A 3J1; [email protected] 2 Experimental Pathology Unit, Department of Pathology, McGill University; Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 0G4 3 Department of Oncology, McGill University; Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 0G4 * Correspondence: [email protected] Table S1. Differentially methylated genes in the Pathways in Cancer KEGG pathway with a log FC ≥ 1.5. Average Average Log Fold Change Differentially Adjusted P Beta Beta ID Gene Name Species (High vs Low Methylated Probes Value Value, Value, Risk) Low High ABL proto-oncogene 1, non- ABL1 Homo sapiens cg13440206, −1.85238 1.39E−06 0.576589 0.259088 receptor tyrosine kinase(ABL1) cg02915920 −1.84042 8.03E−06 0.482846 0.192714 cg21195763 1.685721 3.13E−19 0.573548 0.83358 ADCY2 adenylate cyclase 2(ADCY2) Homo sapiens cg14116052 2.454448 4.3E−24 0.513149 0.885217 ADCY6 adenylate cyclase 6(ADCY6) Homo sapiens cg25196508 3.480923 2.9E−25 0.188362 0.792499 AKT serine/threonine kinase AKT1 Homo sapiens cg14116052 2.454448 4.3E−24 0.513149 0.885217 1(AKT1) bone morphogenetic protein BMP4 Homo sapiens cg08046044 1.527233 3.98E−06 0.049923 0.209543 4(BMP4) cg01873886 1.789942 2.55E−05 0.026254 0.1723 Life 2020, 10, x; doi: FOR PEER REVIEW www.mdpi.com/journal/life Life 2020, 10, x FOR PEER REVIEW 2 of 22 cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor CDKN1B Homo sapiens cg06197769 -

Inhibition of ERK 1/2 Kinases Prevents Tendon Matrix Breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Inhibition of ERK 1/2 kinases prevents tendon matrix breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L. Wunderli1,2,3, Amro A. Hussien1,2, Tino Stauber1,2, Gabriel Flückiger1,2, Maja Bollhalder1,2, Barbara Niederöst1,2, Sandro F. Fucentese1 & Jess G. Snedeker1,2* Tendon extracellular matrix (ECM) mechanical unloading results in tissue degradation and breakdown, with niche-dependent cellular stress directing proteolytic degradation of tendon. Here, we show that the extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is central in tendon degradation of load-deprived tissue explants. We show that ERK 1/2 are highly phosphorylated in mechanically unloaded tendon fascicles in a vascular niche-dependent manner. Pharmacological inhibition of ERK 1/2 abolishes the induction of ECM catabolic gene expression (MMPs) and fully prevents loss of mechanical properties. Moreover, ERK 1/2 inhibition in unloaded tendon fascicles suppresses features of pathological tissue remodeling such as collagen type 3 matrix switch and the induction of the pro-fbrotic cytokine interleukin 11. This work demonstrates ERK signaling as a central checkpoint to trigger tendon matrix degradation and remodeling using load-deprived tissue explants. Tendon is a musculoskeletal tissue that transmits muscle force to bone. To accomplish its biomechanical function, tendon tissues adopt a specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) structure1. Te load-bearing tendon compart- ment consists of highly aligned collagen-rich fascicles that are interspersed with tendon stromal cells. Tendon is a mechanosensitive tissue whereby physiological mechanical loading is vital for maintaining tendon archi- tecture and homeostasis2. Mechanical unloading of the tissue, for instance following tendon rupture or more localized micro trauma, leads to proteolytic breakdown of the tissue with severe deterioration of both structural and mechanical properties3–5. -

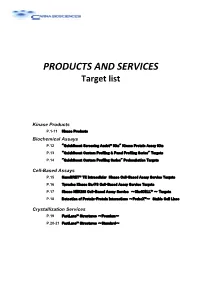

PRODUCTS and SERVICES Target List

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Target list Kinase Products P.1-11 Kinase Products Biochemical Assays P.12 "QuickScout Screening Assist™ Kits" Kinase Protein Assay Kits P.13 "QuickScout Custom Profiling & Panel Profiling Series" Targets P.14 "QuickScout Custom Profiling Series" Preincubation Targets Cell-Based Assays P.15 NanoBRET™ TE Intracellular Kinase Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.16 Tyrosine Kinase Ba/F3 Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.17 Kinase HEK293 Cell-Based Assay Service ~ClariCELL™ ~ Targets P.18 Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions ~ProbeX™~ Stable Cell Lines Crystallization Services P.19 FastLane™ Structures ~Premium~ P.20-21 FastLane™ Structures ~Standard~ Kinase Products For details of products, please see "PRODUCTS AND SERVICES" on page 1~3. Tyrosine Kinases Note: Please contact us for availability or further information. Information may be changed without notice. Expression Protein Kinase Tag Carna Product Name Catalog No. Construct Sequence Accession Number Tag Location System HIS ABL(ABL1) 08-001 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1) 08-401-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [E255K] HIS ABL(ABL1)[E255K] 08-094 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) HIS ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-093 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [T315I] BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-493-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ACK(TNK2) GST ACK(TNK2) 08-196 Catalytic domain -

Oxidized Phospholipids Regulate Amino Acid Metabolism Through MTHFD2 to Facilitate Nucleotide Release in Endothelial Cells

ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04602-0 OPEN Oxidized phospholipids regulate amino acid metabolism through MTHFD2 to facilitate nucleotide release in endothelial cells Juliane Hitzel1,2, Eunjee Lee3,4, Yi Zhang 3,5,Sofia Iris Bibli2,6, Xiaogang Li7, Sven Zukunft 2,6, Beatrice Pflüger1,2, Jiong Hu2,6, Christoph Schürmann1,2, Andrea Estefania Vasconez1,2, James A. Oo1,2, Adelheid Kratzer8,9, Sandeep Kumar 10, Flávia Rezende1,2, Ivana Josipovic1,2, Dominique Thomas11, Hector Giral8,9, Yannick Schreiber12, Gerd Geisslinger11,12, Christian Fork1,2, Xia Yang13, Fragiska Sigala14, Casey E. Romanoski15, Jens Kroll7, Hanjoong Jo 10, Ulf Landmesser8,9,16, Aldons J. Lusis17, 1234567890():,; Dmitry Namgaladze18, Ingrid Fleming2,6, Matthias S. Leisegang1,2, Jun Zhu 3,4 & Ralf P. Brandes1,2 Oxidized phospholipids (oxPAPC) induce endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Here we show that oxPAPC induce a gene network regulating serine-glycine metabolism with the mitochondrial methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase (MTHFD2) as a cau- sal regulator using integrative network modeling and Bayesian network analysis in human aortic endothelial cells. The cluster is activated in human plaque material and by atherogenic lipo- proteins isolated from plasma of patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the MTHFD2-controlled cluster associate with CAD. The MTHFD2-controlled cluster redirects metabolism to glycine synthesis to replenish purine nucleotides. Since endothelial cells secrete purines in response to oxPAPC, the MTHFD2- controlled response maintains endothelial ATP. Accordingly, MTHFD2-dependent glycine synthesis is a prerequisite for angiogenesis. Thus, we propose that endothelial cells undergo MTHFD2-mediated reprogramming toward serine-glycine and mitochondrial one-carbon metabolism to compensate for the loss of ATP in response to oxPAPC during atherosclerosis. -

Less Understood Issues: P21cip1 in Mitosis and Its Therapeutic Potential

Oncogene (2015) 34, 1758–1767 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/15 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW Less understood issues: p21Cip1 in mitosis and its therapeutic potential N-N Kreis, F Louwen and J Yuan p21Cip1 is a multifunctional protein and a key player in regulating different cellular processes. The transcription of p21 is regulated by p53-dependent and -independent pathways. The expression of p21 is increased in response to various cellular stresses to arrest the cell cycle and ensure genomic stability. p21 has been shown to be a tumor suppressor and an oncogene as well. The function of p21 in mitosis has been proposed but not systematically studied. We have recently shown that p21 binds to and inhibits the activity of Cdk1/ cyclin B1, and is important for a fine-tuned mitotic progression. Loss of p21 prolongs the duration of mitosis and results in severe mitotic defects like chromosome segregation and cytokinesis failures promoting consequently genomic instability. Moreover, p21 is dramatically stabilized in mitotic tumor cells upon treatment with mitotic agents like paclitaxel or mitotic kinase inhibitors. Increased p21 is mainly localized in the cytoplasm and associates with cell survival indicating a crucial role of p21 in susceptibility to mitotic agents in tumor cells. In this review we will briefly summarize the structure and general physiological functions as well as regulation of p21, discuss in detail its role in mitosis and its potential to serve as a therapeutic target. Oncogene (2015) 34, 1758–1767; doi:10.1038/onc.2014.133; published online 26 May 2014 INTRODUCTION arguing about the role of p21 as a classical tumor suppressor. -

Targeted Genetic Dependency Screen Facilitates Identification Of

Targeted genetic dependency screen facilitates identification of actionable mutations in FGFR4, MAP3K9, and PAK5 in lung cancer Shameem Fawdara, Eleanor W. Trottera,1, Yaoyong Lib,1, Natalie L. Stephensona, Franziska Hankea, Anna A. Marusiaka, Zoe C. Edwardsa, Sara Ientilea, Bohdan Waszkowyczc, Crispin J. Millerb, and John Brognarda,2 aSignalling Networks in Cancer Group, bApplied Computational Biology and Bioinformatics Group, and cDrug Discovery Unit, Cancer Research UK, Paterson Institute for Cancer Research, University of Manchester, Manchester M20 4BX, United Kingdom Edited by Ingo K. Mellinghoff, Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, and accepted by the Editorial Board June 17, 2013 (received for review March 20, 2013) Approximately 70% of patients with non–small-cell lung cancer and required to maintain cancer cell survival (8, 9). Labor-intensive present with late-stage disease and have limited treatment op- functional studies must be performed to validate many of these tions, so there is a pressing need to develop efficacious targeted potential drivers (8). More recently, several approaches are therapies for these patients. This remains a major challenge as the coming to the forefront to more efficiently identify genetic de- underlying genetic causes of ∼50% of non–small-cell lung cancers pendencies from cancer cells for which whole genome or exome remain unknown. Here we demonstrate that a targeted genetic sequencing has been performed (10). These include cross-species dependency screen is an efficient approach to identify somatic comparisons, insertional mutagenesis screens, and RNAi screening fi fi cancer alterations that are functionally important. By using this (10). There are bene ts and de ciencies with many of these fi approaches, as highlighted by Eifert et al. -

Insulin and Glucose Alter Death-Associated Protein Kinase 3 (DAPK3) DNA Methylation

Page 1 of 89 Diabetes Insulin and glucose alter death-associated protein kinase 3 (DAPK3) DNA methylation in human skeletal muscle Jonathan M. Mudry1, David G. Lassiter1, Carolina Nylén1, Sonia García-Calzón2, Erik Näslund3, Anna Krook2, Juleen R. Zierath1,2,4. Running title: DAPK3 DNA methylation in human skeletal muscle 1Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Integrative Physiology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. 2Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, Integrative Physiology, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. 3Division of Surgery, Department of Clinical Sciences, Danderyd Hospital, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden. 4Section of Integrative Physiology, The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research, Faculty of Health and Medical Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. Juleen R. Zierath Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Section of Integrative Physiology, Karolinska Institutet, von Eulers väg 4a, SE 171 77 Stockholm, Sweden Phone: +46 (0)8 524 87581 Fax: +46 (0) 8 33 54 36 E-mail: [email protected] Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online December 23, 2016 Diabetes Page 2 of 89 Abstract DNA methylation is altered by environmental factors. We hypothesized DNA methylation is altered in skeletal muscle in response to either insulin or glucose exposure. We performed a genome-wide DNA methylation analysis in muscle from healthy men before and after insulin exposure. DNA methylation of selected genes was determined in muscle from healthy and type 2 diabetic men before and after a glucose tolerance test. Insulin altered DNA methylation in the 3’UTR of the calcium pump ATP2A3 gene. Insulin increased DNA methylation in the gene body of DAPK3, a gene involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis and autophagy. -

Dynamics of Dual Specificity Phosphatases and Their Interplay with Protein Kinases in Immune Signaling Yashwanth Subbannayya1,2, Sneha M

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/568576; this version posted March 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Dynamics of dual specificity phosphatases and their interplay with protein kinases in immune signaling Yashwanth Subbannayya1,2, Sneha M. Pinto1,2, Korbinian Bösl1, T. S. Keshava Prasad2 and Richard K. Kandasamy1,3,* 1Centre of Molecular Inflammation Research (CEMIR), and Department of Clinical and Molecular Medicine (IKOM), Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway 2Center for Systems Biology and Molecular Medicine, Yenepoya (Deemed to be University), Mangalore 575018, India 3Centre for Molecular Medicine Norway (NCMM), Nordic EMBL Partnership, University of Oslo and Oslo University Hospital, N-0349 Oslo, Norway *Correspondence: Richard K. Kandasamy ([email protected]) Abstract Dual specificity phosphatases (DUSPs) have a well-known role as regulators of the immune response through the modulation of mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs). Yet the precise interplay between the various members of the DUSP family with protein kinases is not well understood. Recent multi-omics studies characterizing the transcriptomes and proteomes of immune cells have provided snapshots of molecular mechanisms underlying innate immune response in unprecedented detail. In this study, we focused on deciphering the interplay between members of the DUSP family with protein kinases in immune cells using publicly available omics datasets. Our analysis resulted in the identification of potential DUSP- mediated hub proteins including MAPK7, MAPK8, AURKA, and IGF1R. Furthermore, we analyzed the association of DUSP expression with TLR4 signaling and identified VEGF, FGFR and SCF-KIT pathway modules to be regulated by the activation of TLR4 signaling. -

Discovery of Potent and Selective MRCK Inhibitors with Therapeutic

Published OnlineFirst January 30, 2018; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2870 Cancer Translational Science Research Discovery of Potent and Selective MRCK Inhibitors with Therapeutic Effect on Skin Cancer Mathieu Unbekandt1, Simone Belshaw2, Justin Bower2, Maeve Clarke2, Jacqueline Cordes2, Diane Crighton2, Daniel R. Croft2, Martin J. Drysdale2, Mathew J. Garnett3, Kathryn Gill2, Christopher Gray2, David A. Greenhalgh4, James A.M. Hall3, Jennifer Konczal2, Sergio Lilla5, Duncan McArthur2, Patricia McConnell2, Laura McDonald2, Lynn McGarry6, Heather McKinnon2, Carol McMenemy4, Mokdad Mezna2, Nicolas A. Morrice5, June Munro1, Gregory Naylor1, Nicola Rath1, Alexander W. Schuttelkopf€ 2, Mairi Sime2, and Michael F. Olson1,7 Abstract The myotonic dystrophy–related Cdc42-binding kinases an autophosphorylation site, enabling development of a phos- MRCKa and MRCKb contribute to the regulation of actin–myosin phorylation-sensitive antibody tool to report on MRCKa status in cytoskeleton organization and dynamics, acting in concert with tumor specimens. In a two-stage chemical carcinogenesis model the Rho-associated coiled-coil kinases ROCK1 and ROCK2. The of murine squamous cell carcinoma, topical treatments reduced absence of highly potent and selective MRCK inhibitors has MRCKa S1003 autophosphorylation and skin papilloma out- resulted in relatively little knowledge of the potential roles of growth. In parallel work, we validated a phospho-selective anti- these kinases in cancer. Here, we report the discovery of the body with the capability to monitor drug pharmacodynamics. azaindole compounds BDP8900 and BDP9066 as potent and Taken together, our findings establish an important oncogenic selective MRCK inhibitors that reduce substrate phosphorylation, role for MRCK in cancer, and they offer an initial preclinical proof leading to morphologic changes in cancer cells along with inhi- of concept for MRCK inhibition as a valid therapeutic strategy. -

Table S1. Potency of BMS-690514 in Enzymatic Kinase Assays Kinase

Table S1. Potency of BMS-690514 in enzymatic kinase assays Kinase IC50, nmol/L EGFR 5 HER2 19 HER4 60 VEGFR1 50 VEGFR2 50 VEGFR3 25 IGF-1R >50,000 FLT3 110 Lck 220 FES 900 EMT >5000 SYK 4300 JAK3 5000 Cdk2/cyclin E 10000 PKA 280 PKCα 460 CAMKII 170 Akt1 >5000 Mek1 >10000 GSK3β >5000 IKKβ >10000 Table S2. KinomeScan Profile of BMS-690514 Target % control at 1 µM* AAK1 59 ABL1 4.8 ACK 14 ACTR2 100 ACTR2B 18 ADCK3 64 ADCK4 78 AKT1 68 AKT2 100 AKT3 78 ALK 100 ALK1 100 ALK2 86 ALK4 37 AMPKA1 87 AMPKA2 100 ANKRD3 56 ARG 1.4 AURA 100 AURB 100 AURC 100 AXL 100 BIKE 89 BLK 1.4 BMPR1A 78 BMPR1B 11 BMPR2 90 BMX 35 BRAF 100 BRK 20 BRSK1 100 BRSK2 57 BTK 69 CAMK1A 71 CAMK1D 56 CAMK1G 81 CAMK2A 53 CAMK2B 67 CAMK2D 46 CAMK2G 87 CAMK4 100 CAMKK1 100 CAMKK2 100 CAMLCK 100 CDC2L1_ISO4 100 CDC2L2_ISO1 100 CDK11 100 CDK2 100 CDK3 100 CDK5 100 CDK7 35 CDK8 100 CDK9 98 CDKL2 100 CHK1 70 CHK2 78 CK1A2 53 CK1D 52 CK1E 54 CK1G1 75 CK1G2 100 CK1G3 97 CK2A1 100 CK2A2 100 CLIK1 100 CLK1 72 CLK2 59 CLK3 67 CLK4 84 CRIK 34 CSK 48 DAPK1 79 DAPK2 89 DAPK3 68 DCAMKL1 100 DCAMKL2 100 DCAMKL3 100 DDR1 18 DDR2 39 DLK 91 DMPK1 52 DMPK2 100 DRAK1 100 DRAK2 100 DYRK1B 72 EGFR 0 EPHA1 8.1 EPHA2 44 EPHA3 31 EPHA4 48 EPHA5 93 EPHA6 73 EPHA7 100 EPHA8 24 EPHB1 53 EPHB2 76 EPHB3 27 EPHB4 50 ERK1 100 ERK2 86 ERK3 100 ERK4 100 ERK5 100 ERK7 93 FAK 100 FER 79 FES 29 FGFR1 72 FGFR2 100 FGFR3 100 FGFR4 100 FGR 1.3 FLT1 100 FLT3 37 FLT4 97 FMS 21 FRK 6.2 FUSED 80 FYN 4.5 GAK 1.9 GCK 94 GSK3A 36 GSK3B 87 HCK 3 HH498 7.8 HIPK1 100 HPK1 77 IGF1R 100 IKKA 70 IKKB 83 IKKE 90 INSR 100 IRAK3