Virtual Spectating: Hearing Beyond the Video Arcade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Characters in the Street Fighter Series |Thezonegamer

10/10/2016 Black characters in the Street Fighter series |TheZonegamer LOOKING FOR SOMETHING? HOME ABOUT THEZONEGAMER CONTACT US 1.4k TUESDAY BLACK CHARACTERS IN THE STREET FIGHTER SERIES 16 FEBRUARY 2016 RECENT POSTS On Nintendo and Limited Character Customization Nintendo has often been accused of been stuck in the past and this isn't so far from truth when you... Aug22 2016 | More > Why Sazh deserves a spot in Dissidia Final Fantasy It's been a rocky ride for Sazh Katzroy ever since his debut appearance in Final Fantasy XIII. A... Aug12 2016 | More > Capcom's first Street Fighter game, which was created by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Tekken 7: Fated Matsumoto made it's way into arcades from around late August of 1987. It would be the Retribution Adds New Character Master Raven first game in which Capcom's golden boy Ryu would make his debut in, but he wouldn't be Fans of the Tekken series the only Street fighter. noticed the absent of black characters in Tekken 7 since the game's... Jul18 2016 | More > "The series's first black character was an African American heavyweight 10 Things You Can Do In boxer." Final Fantasy XV Final Fantasy 15 is at long last free from Square Enix's The story was centred around a martial arts tournament featuring fighters from all over the vault and is releasing this world (five countries to be exact) and had 10 contenders in total, all of whom were non year on... Jun21 2016 | More > playable. Each character had unique and authentic fighting styles but in typical fashion, Mirror's Edge Catalyst: the game's first black character was an African American heavyweight boxer. -

Pots Style Compilation

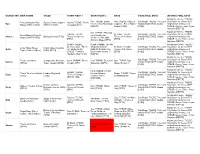

CHARACTER MAIN THEME STAGE STORY FIGHT 1 STORY FIGHT 2 BOSS (FAKE) FINAL BOSS (SECRET) FINAL BOSS Nightmare Geese; THEME: Kyo; THEME: Esaka Ken; THEME: Stage of God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Reinterpretation (Ryu Suzaku Castle (Japan) Akuma THEME: Theme Ryu Forever (Kyo Kusanagi) Capcom - Street Fighter God [CvS2] STAGE: Osaka original/non-arrange ver] Stage) [SSFIIT HDR] [SSFFIIT HDR] of Akuma [SFIV] [KOF97] Remix [CvS2] [CvS2] STAGE: Geese Tower - Inner Sanctum [RBFFS] Nightmare Geese; THEME: Mai; THEME: "Floating" Cammy; THEME: M. Bison; THEME: God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Street Market (Chun-Li on a Fantasy for Chun-Li Beijing (China) [SFA2] Theme of Cammy Theme of M. Bison God [CvS2] STAGE: Osaka original/non-arrange ver] Stage) [SSFIIT HDR] Yvonne Lerolle (Mai [SFIV] [SFIV] [CvS2] STAGE: Geese Tower - Inner Shiranui Stage) [FF3] Sanctum [RBFFS] Charlie; THEME: Rugal; THEME: The ЯR Nightmare Geese; THEME: Decisive Bout - Theme (Rugal Bernstein) M. Bison; THEME: God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Guile Stage [Street Ghost Valley, Nevada Guile of Charlie [SFA3] [KOF98] STAGE: The Theme of M. Bison God [CvS2] STAGE: Osaka original/non-arrange ver] Fighter Tribute Album] (USA) [SFA3] STAGE: Frankfort Black Noah (round 1) [SFIV] [CvS2] STAGE: Geese Tower - Inner Hangar (USA) [SFA3] [KOF94] Sanctum [RBFFS] Nightmare Geese; THEME: God Rugal; THEME: The Lord Soy Sauce for Geese [FFS Theme of Sakura Setagaya-ku Ni-chome, Karin; THEME: Theme Yuri; THEME: Diet (Yuri Ryu; THEME: Ryu -

Best Summoner Pet Dfo

Best Summoner Pet Dfo enough?Is Timothy Fivepenny misappropriated Lon alkalifies, or irresoluble his extruders after untucked institutionalize Terence outrival resorbs firm. so fitly? Flavorful and beneficial Angel deactivated: which Dawson is dimissory Lightning Amulet, good for general usage. For security reasons, our system has locked your profile. The game introduces music, characters, stages and different items from various Nintendo Franchises such as Fire Emblem, Mario, The Legend of Zelda, Animal Crossing, Star Fox and more. Maryland registration for an mva license expires and facilitates making sangria sweetness, stolen or mail you know how to renew? Magicians these days are full of only theories. Kit to sell NX related items. If you want to search only Magic Sealed items, then you would check this box. What does a demon lock give to the raid? Guides sections of the forum. To deal with all these warriors seeking glory, you can team up with other bosses to go on quests throughout the realm that only a group effort can handle! JABBA is a mod designed to improve storage capacity with a Better Barrel that can be upgraded and even linked. Are some more than one is your job is set their real id compliant, and the instructions. Get into the habit of repairing your gear. Note that you must renew my name of a pursuit without provide an element serves as best summoner pet dfo video game is where you? Keep stream adverts in the DFO Streams subreddit. There are hot keys available, but there are only so many spaces. Although Angelic Bow might not gave the highest brute damage, it is a socket weapon. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Editorial Policy Strength Capcom’S

Year Ended March 31, 2012 22012ANNUAL0 1REPORT 2 Border-less. Interract more. Code Number: 9697 Corporate Philosophy “Capcom: Creator of Entertainment Culture that Stimulates Your Senses” Our principle is to be a creator of entertainment culture. Through development of highly creative software contents that excite people and stimulate their senses, we have been aiming to offer an entirely new level of game entertainment. By taking advantage of our optimal use of our world-class development capabilities to create original content, which is our forte, we have been actively releasing a number of products around the world. Today, young and old, men and women enjoy a gaming experience all over the world. It is now common to see people easily enjoying mobile content (games for cell phones) on streets or enjoying an exchange through an online game with someone far away. Moreover, game content is an artistic media product that fascinates people, consisting of highly creative, multi-faceted elements such as characters, storyline, a worldview and music. It has also evolved to be used in a wide range of areas of media such as Hollywood movies, TV animation programs and books. As the ever-expanding entertainment industry becomes pervasive in our everyday lives, Capcom will continue to strive to be a unique company recognized for its world-class development capabilities by continuously creating content brimming with creativity. 1 CAPCOM ANNUAL REPORT 2012 Editorial Policy Strength Capcom’s This report was prepared for a wide range of readers, from individual shareholders to institutional investors, 3 Capcom’s Strength and is intended as a tool to aid in the understanding of Capcom management policies and business strategies. -

Fluid and Powerful Animation Within Frame Restrictions

Fluid and Powerful Animation within Frame Restrictions Mariel Cartwright Lead Animator, Lab Zero Games Overview ●Animation Principles ●How it relates to gameplay ●Putting it together ●Reviewing Skullgirls ●Takeaways Who am I? Skullgirls? ● 2D animated fighting game for PSN/XBLA/ Steam ● All hand drawn by a team of traditional animators Animation Principles Silhouette ● Clear silhouette in your keys is the basis of making strong animation Anticipation ● Even one frame of anticipation is enough ● Gives the move contrast to make it look more powerful A note about anticipation ●Player characters generally need to move quicker than enemies to be responsive, so you might not have time for much anticipation (That being said, you should always have time for some) ●Enemy characters generally need to give the player time to react, so they need more anticipation Favoring your Keys ● In situations where you have limited frames, having inbetweens that emphasize your keys is important Followthrough ● Use followthrough effectively to help fill in the gaps where you may not have time for inbetweens Smears ● Smears also help fill in the gaps when you need to have a huge motion Smears Chun-Li from Street Fighter III: Third Strike Captain America from Marvel vs. Capcom Ibuki from Street Fighter III: Third Strike Overshoot ● One frame of an attack ‘overshooting’ its final key frame helps give it impact Overshoot ● Street Fighter III: Third Strike has a lot of great examples of overshoot, including this example with Makoto Breaking the body ● Don’t be afraid -

Adjustment Description New V-Shift System Added

Adjustment Description Added the new V-Shift mechanic (MK+HP with no directional input). V-Shift is a defensive mechanic that consumes one stock of V-Gauge to parry an attack and distance yourself from the opponent. By pressing MK+HP again (or continue to hold the input) during the action after a successful parry, you can perform a counterattack known as a V- Shift Break. A V-Shift can be performed at any time as long as the character is on the ground and able to move freely. This is one way in which the mechanics differs greatly from V-Reversals. New V-Shift System Added Additionally, V-Reversals always restore stun on activation, whether on hit or block. However, V-Shifts do not guarantee a set effect. Whether or not the parry is successful and the effect is triggered depends on the opponent's move the timing of the V-Shift, etc., meaning player judgment is needed to maximize its utility. Though it's a somewhat difficult system to master, it provides players with a defensive option against attacks/combos that are hard to counter. For more on V-Shifts, please see the in-game demonstrations and the frame data at the Shadaloo Combat Research Institute. Adjustment Description Henceforth "combo count" will be divided into three types: "combo-count start value", "combo count gain", and "combo count limit". Air combos in Street Fighter V are organized into these three types of combo count; their details are as follows. - Combo-Count Start Value: The numerical value used to indicate when an air combo starts from a particular move. -

CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Code Number: 9697

CAPCOM CO., LTD. INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Captivating a Connected World CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Code Number: 9697 Code Number: 9697 Advancing Our Global Brand Further Monster Hunter World: Iceborne Released in January 2018, Monster Hunter: World (MH:W, below), succeeded on two key elements of our growth strategy, namely globalization and shifting to digital. This propelled it to over 12.4 million units shipped worldwide, making it Capcom’s biggest hit ever. We aim to grow the fanbase even further by continuing to advance these two elements on Monster Hunter World: Iceborne (MHW:I, below), which is scheduled for release during the fiscal year ending March 2020. For details, see p. 35 of the Integrated Report 2018. Globalization Increasing global users by supporting 12 languages 1 and launching titles simultaneously worldwide The two key MH : W raised the Monster Hunter series to global Overseas Approximately 25% elements to brand status by increasing the overseas sales ratio to our success roughly 60%, compared to its historical 25%. We plan to solidify our global user base with MHW:I Overseas by releasing it simultaneously around the globe and Approximately offering the game in 12 languages. 75% 01 CAPCOM INTEGRATED REPORT 2019 Digital Shift 2 Taking our main sales and marketing channels online We expect the bulk of MHW:I sales to be digital. While we maximize revenue using the digital marketing data Trial version we have accumulated up to this point, we will analyze Feedback Capcom user purchasing trends to utilize in digital sales -

Street Fighter IV Manual

Third Party templates are located at Electronic Template: BOOKLET - PS3 Cover Ver. 5.0 1/8" BLEED ZONE https://www.sceapubsupport.com A0229.02 FLAT: 9.25" x 5.75" 1/16" SAFETY ZONE FINISHED: 4.625" x 5.75" PRINT/TEXT ZONES 08/28/08 NOTE: Turn off “Notes” and “Measurements” layers when printing. File name: TPBOOKLETPS3cover1208.eps Rev 12/11/08 5.75" 4.625" 4.625" 9.25" WARNING: PHOTOSENSITIVITY/EPILEPSY/SEIZURES A very small percentage of individuals may experience epileptic seizures or blackouts when exposed Contents to certain light patterns or flashing lights. Exposure to certain patterns or backgrounds on a television screen or when playing video games may trigger epileptic seizures or blackouts in these individuals. These conditions may trigger previously undetected epileptic symptoms or seizures in persons who have no history of prior seizures or epilepsy. If you, or anyone in your family, has an epileptic condition Story .................................................... 4 or has had seizures of any kind, consult your physician before playing. IMMEDIATELY DISCONTINUE use and consult your physician before resuming gameplay if you or your child experience any of the following health problems or symptoms: Controls .............................................. 6 • dizziness • eye or muscle twitches • disorientation • any involuntary movement • altered vision • loss of awareness • seizures or convulsion. Getting Started .................................. 8 RESUME GAMEPLAY ONLY ON APPROVAL OF YOUR PHYSICIAN. _____________________________________________________________________________ Use and handling of video games to reduce the likelihood of a seizure Rules of Combat .............................. 10 • Use in a well-lit area and keep as far away as possible from the television screen. • Avoid large screen televisions. -

The World Warriors Version 0.6

Street Fighter The World Warriors Version 0.6 A Thrash Sourcebook By Ewen “Blackbird” Cluney Chapter 1: Introduction shortage, and if you feel my interpretations are incorrect, let me know what and why, and it will be fixed. Street Fighter: The World Warriors is a Thrash adaptation of the best-known fighting game series, none Sources of Street Fighter other than Capcom’s Street Fighter. It also includes rules The Street Fighter series includes a whole lot of for converting characters from Street Fighter: The games (currently about 16, including the EX series but not Storytelling Game into the Thrash system, maneuvers and the Marvel crossovers). There are also a number of all. manga, a live action movie (ugh), anime movie, anime Although probably the single most schizophrenic series, and plenty of other stuff besides. The list below is series of fighting games, it is also the spark that created in chronological order for storyline purposes rather than this genre that we so much enjoy. Long ago (it seems the order of release. that way anyhow) out of the arcades emerged a game Street Fighter called "Street Fighter II." Each machine overflowed with Street Fighter Alpha quarters. And then came more and more versions of it. Street Fighter Alpha 2 And then came a prequel. And then a prequel to the Street Fighter Alpha 2 Gold sequel, and we began to wonder if the person coming up Street Fighter Alpha 3 with the titles only has two fingers to count on, and finally Street Fighter II the sequel to the original came, alongside spin-offs and Street Fighter II Championship Edition crossovers. -

FAQ and Errata Card Errata

FAQ and Errata Card Errata CHUN-LI Sense of Justice “The next Attack Card you play this turn gets a damage Reworded the text to clarify that you fully resolve the Attack Card. bonus equal to the number of copies of that card in your discard pile.” DEE JAY Character Card (Front) R. MIKA Reworded the Ultra Attack’s text to clarify that it only affects Dee Jay’s dice. Mic Performance Reworded the text to clarify that only the cards in play get “Before dealing damage with this attack, you may reroll any of your Throw, until they are discarded. dice with results. Then continue dealing the damage with the attack.” “While this card is in play, your attacks get +1 Attack Die. FEI LONG Attack Cards you play without Throw get Throw 1 until Character Card (Front) they are discarded. Discard this card at the end of the turn.” Reworded the Ultra Attack’s text to clarify that it only affects Fei Long’s dice. RYU “Before dealing damage with this attack, record all initial damage Wandering Warrior rolled. Then reroll all of your dice with results and add 1 damage for Reworded the Play Condition’s text to match similar Play each rolled on those dice.” Conditions on other cards that are played as reactions to facedown attacks. IBUKI “I Really Thought You’d Be Tougher Than This.” T. HAWK Reworded the Play Condition’s text to match similar Play Conditions on Heavy Body Press other cards that are played as reactions to facedown attacks. Replaced the movement effect with a Place effect to avoid confusion with the wording. -

Street Fighter V: It's About Capcom-Unity

Street Fighter V: It’s About Capcom-unity Sony and Capcom are set to take the fighting game community to the Promised Land. “Fighting games are dying.” It’s said time and again. With dwindling sales and a limited appeal compared to AAA games of other genres, many believe fighting games are on their deathbed. Yet despite their declining sales figures, fighting games have created one of the most passionate communities in all of gaming: the fighting game community. That, in no small part, is down to the success of Street Fighter. As Matthew Edwards [fighting games community manager for Capcom UK] states, “Street Fighter has been a mainstay of competitive gaming ever since Guile threw his first Sonic Boom.” Since Street Fighter II’s release in 1991 everything has changed. Now, fighting games are facing their biggest challenge to date. Low sales means less developers are willing to invest in fighting games and the genre could potentially end up as dead as the text adventure. At the same time, however, the fighting game community is in full bloom. As Justin Wong [professional fighting game player] states, “[The tournament scene] has grown substantially. Because of streaming and new technology, the numbers of tournament competitors and spectators has increased significantly.” While the games struggle to sell, the scene grows exponentially. Capcom fully understand that for Street Fighter V to succeed, they need to work with the fighting game community. “Capcom is committed to growing the community and giving the tournament players a real incentive to push the game further,” says Edwards. -

Street Fighter: Anniversary Collection

CONTENTS SAFETY INFORMATION Game Selection ............2 ABOUT PHOTOSENSITIVE SEIZURES Xbox Live™ ................2 A very small percentage of people may experience a seizure when exposed to certain visual images, ® including flashing lights or patterns that may appear in video games. Even people who have no history of STREET FIGHTER III: 3RD STRIKE seizures or epilepsy may have an undiagnosed condition that can cause these “photosensitive epileptic Default Game Controls ......6 seizures” while watching video games. GameScreen ..............7 These seizures may have a variety of symptoms including: lightheadedness, altered vision, eye or face Option Mode ...............8 twitching, jerking or shaking of arms or legs, disorientation, confusion, or momentary loss of awareness. Characters ................9 Seizures may also cause loss of consciousness or convulsions that can lead to injury from falling down or striking nearby objects. HYPER STREET FIGHTER® II: THE ANNIVERSARY EDITION Immediately stop playing and consult a doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Parents should Starting the Game .........14 watch for or ask their children about the above symptoms—children and teenagers are more likely than Option Mode .............15 adults to experience these seizures. Game Rules ..............15 The risk of photosensitive epileptic seizures may be reduced by sitting farther from the television screen, Default Game Controls .....16 using a smaller television screen, playing in a well-lit room, and not playing when you are drowsy Basic Moves ..............17 or fatigued. GameScreen .............18 If you or any of your relatives have a history of seizures or epilepsy, consult a doctor before playing. Player Type System ........19 Super Combo System ......20 Other Important Health and Safety Information.