Learning from Television, What the Research Says

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Docuent Renee

DOCUENT RENEE ED 099 243 SI 018 610 TITLE Situation ReportGhana, Guyana, India, Japan, Kenya, Khmer Republic, Nepal, Niger, Republic of Vietnam, Senegal, Thailand, and Trinidad and Tobago. INSTITUTION International Planned Parenthood Federation, London (England). PUB DATE 74 NOTE 90p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$4.20 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Contraception; Demography; *Family Planning; *Foreign Countries; *Population Trends; Programs; Resource Materials; Social Welfare; *Statistical Data ABSTRACT Data relating to population and family planning in twelve foreign countries are presented in these situation reports. Countries included are Ghana, Guyana, India, Japan, Kenya, Khmer Republic, Nepal, Niger, Republic of Vietnam, Senegal, Thailand,and Trinidad and Tobago. Information is provided under two topics, general background and family planning situation, where appropriate and if it is available. General background covers ethnic groups, language, religion, economy, communication /education,medical/social welfare, and statistics on population, birth, and death rates.Family planning situation considers family planningassociations and personnel; government attitudes; legislation; family planning services; education/information; training opportunities for individuals, families, and medical personnel; research and evaluation; program plans; government programs; and related supporting organizations. Bibliographic sources are given.(DT) tj 1 DIPARTMS NT Oi HEALTH. ADUCATIONAWMFARE Distribution * NATIONAL INTTITOTO Situation 601,411 TION INn 00t uM1 141uA HI 14 /(11.10 putt ()I IA, v wl 1 .%1 I)I kOM Report Int ui lisuk,%,1101u.A/1 r)1/1(.1% PoNt %II A ok 010110,1% %IA,/ 0 1,0 Nut bl t1 .41e.: Y lot PIT %FPO 011 n At ItA O1u .b'.111 t111 01 woo fOut AI ION 1I IPol,t0,4 kqe 1.01 t toition I cmintry GHANA Date JUNE 1974 to,! Pa(t.i triota! 113. -

Dvd Digital Cinema System Systema Dvd Digital Cinema Sistema De Cinema De Dvd Digital Th-A9

DVD DIGITAL CINEMA SYSTEM SYSTEMA DVD DIGITAL CINEMA SISTEMA DE CINEMA DE DVD DIGITAL TH-A9 Consists of XV-THA9, SP-PWA9, SP-XCA9, and SP-XSA9 Consta de XV-THA9, SP-PWA9, SP-XCA9, y SP-XSA9 Consiste em XV-THA9, SP-PWA9, SP-XCA9, e SP-XSA9 STANDBY/ON TV/CATV/DBS AUDIO VCR AUX FM/AM DVD TITLE SUBTITLE DECODE AUDIO ZOOM DIGEST TIME DISPLAY RETURN ANGLE CHOICE SOUND CONTROL SUBWOOFER EFFECT VCR CENTER TEST TV REAR-L SLEEP REAR-R SETTING TV RETURN FM MODE 100+ AUDIO/ PLAY TV/VCR MODE CAT/DBS ENTER SP-XSA9 SP-XCA9 SP-XSA9 THEATER DSP POSITION MODE TV VOLCHANNEL VOLUME TV/VIDEO MUTING B.SEARCH F.SEARCH /REW PLAY FF DOWN TUNING UP REC STOP PAUSE MEMORY STROBE DVD MENU RM-STHA9U DVD CINEMA SYSTEM SP-PWA9 XV-THA9 INSTRUCTIONS For Customer Use: INSTRUCCIONES Enter below the Model No. and Serial No. which are located either on the rear, INSTRUÇÕES bottom or side of the cabinet. Retain this information for future reference. Model No. Serial No. LVT0562-010A [ UW ] Warnings, Cautions and Others Avisos, Precauciones y otras notas Advertêcias, precauções e outras notas Caution - button! CAUTION Disconnect the XV-THA9 and SP-PWA9 main plugs to To reduce the risk of electrical shocks, fire, etc.: shut the power off completely. The button on the 1. Do not remove screws, covers or cabinet. XV-THA9 in any position do not disconnect the mains 2. Do not expose this appliance to rain or moisture. line. The power can be remote controlled. -

Dvd Digital Cinema System

THS3[UW]-01cov1.fm Page 1 Wednesday, April 28, 2004 2:38 PM DVD DIGITAL CINEMA SYSTEM SYSTEMA DVD DIGITAL CINEMA SISTEMA DE CINEMA DE DVD DIGITAL TH-S3 Consists of XV-THS3, SP-WS3, and SP-THS3F Consta de XV-THS3, SP-WS3 y SP-THS3F Consta do XV-THS3, SP-WS3 e SP-THS3F INSTRUCTIONS MANUAL DE INSTRUCCIONES INSTRUÇÕES GVT0133-013A [UW] TH-S3[UW].book Page 1 Tuesday, April 27, 2004 5:54 PM Warnings, Cautions and Others/Avisos, precauciones y otras notas/Advertências, precauções e outras notas CAUTION CAUTION To reduce the risk of electrical shocks, fire, etc.: • Do not block the ventilation openings or holes. 1. Do not remove screws, covers or cabinet. (If the ventilation openings or holes are blocked by a 2. Do not expose this appliance to rain or moisture. newspaper or cloth, etc., the heat may not be able to get out.) • Do not place any naked flame sources, such as lighted candles, on the apparatus. PRECAUCIÓN • When discarding batteries, environmental problems must be Para reducir el riesgo de descargas eléctricas, fuego, etc.: considered and local rules or laws governing the disposal of 1. No quitar los tornillos, tapas o caja. these batteries must be followed strictly. 2. No exponer el aparato a la lluvia ni a la húmedad. • Do not expose this apparatus to rain, moisture, dripping or splashing and that no objects filled with liquids, such as vases, shall be placed on the apparatus. PRECAUÇÃO Para reduzir riscos de choques elétricos, incêndio, etc.: 1. Não remova parafusos e tampas ou desmonte a caixa. -

Country Profiles

1 2017 ANNUAL2018 REPORT:ANNUAL UNFPA-UNICEF REPORT GLOBAL PROGRAMME TO ACCELERATE ACTION TO END CHILD MARRIAGE COUNTRY PROFILES UNFPA-UNICEF GLOBAL PROGRAMME TO ACCELERATE ACTION TO END CHILD MARRIAGE The Global Programme to Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage is generously funded by the Governments of Belgium, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, the United Kingdom and the European Union and Zonta International. Front cover: © UNICEF/UNI107875/Pirozzi © United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) August 2019 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH COUNTRYCOUNTRY PROFILE PROFILE © UNICEF/UNI179225/LYNCH BANGLADESH COUNTRY PROFILE 3 2 RANGPUR 1 1 2 2 1 3 2 1 1 Percentage of young women SYLHET (aged 20–24) married or in RAJSHAHI 59 union by age 18 DHAKA 2 2 Percentage of young women 1 KHULNA (aged 20–24) married or in CHITTAGONG 22 union by age 15 Percentage of women aged 20 to 24 years who were first married or in BARISAL union before 1 age 18 3 2 0-9% 2 10-19% 20-29% 30-39% 40-49% 50-59% UNFPA + UNICEF implementation 60-69% 70-79% UNFPA implementation 80<% UNICEF implementation 1 Implementation outcome 1 (life skills and education support for girls) 2 Implementation outcome 2 (community dialogue) 3 3 Implementation outcome 3 (strengthening education, 2.05 BIRTHS PER WOMAN health and child protection systems) Total fertility rate (average number of children a woman would have by Note: This map is stylized and not to scale. It does not reflect a position by the end of her reproductive period if her experience followed the currently UNFPA or UNICEF on the legal status of any country or area or the delimitation of any frontiers. -

Winter 2020 Film Calendar

National Gallery of Art Film Winter 20 Special Events 11 Abbas Kiarostami: Early Films 19 Checkerboard Films on the American Arts: Recent Releases 27 Displaced: Immigration Stories 31 African Legacy: Francophone Films 1955 to 2019 35 An Armenian Odyssey 43 Hyenas p39 Winter 2020 opens with the rarely seen early work of Abbas Kiarostami, shown as part of a com- plete retrospective of the Iranian master’s legacy screening in three locations in the Washington, DC, area — the AFI Silver Theatre, the Freer Gallery of Art, and the National Gallery of Art. A tribute to Check- erboard Film Foundation’s ongoing documentation of American artists features ten of the foundation’s most recent films. Displaced: Immigration Stories is organized in association with Richard Mosse: Incom- ing and comprises five events that allow audiences to view the migrant crisis in Europe and the United States through artists’ eyes. African Legacy: Franco- phone Films 1955 to 2019 celebrates the rich tradition of filmmaking in Cameroon, Mauritania, Ivory Coast, Senegal, and Niger, including filmmakers such as Med Hondo, Timité Bassori, Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, Ousmane Sembène, Djibril Diop Mambéty, and Moustapha Alassane as well as new work by contemporary Cameroonian artist Rosine Mbakam. An Armenian Odyssey, organized jointly with Post- Classical Ensemble, the Embassy of Armenia, the National Cinema Center of Armenia, and the Freer Gallery, combines new films and recent restorations, including works by Sergei Parajanov, Kevork Mourad, Hamo Bek-Nazaryan, and Rouben Mamoulian, as well as musical events at Washington National Cathedral. The season also includes a number of special events and lectures; filmmaker presentations with Rima Yamazaki and William Noland; and recent documentaries such as Cunningham; Leaving Home, Coming Home: A Portrait of Robert Frank; Museum Town; The Hottest August; Architecture of Infinity; and It Will Be Chaos. -

Stated Goals of the Indian Program. If Satellite Television Is to Be

DOCt HEST R?,3114Z ED 032 766 EM 007 355 By- Wilbur; Nelson. Lyle Cormvnication Satellites for Education and Dever.-.4prtent -The Case of India.Volume Two. Svcriford Univ.. Calif. Inst. for CommunicationResearch. Spons Agency-Agency for Internc/tionalDevelopment, Washington. D.C. Pub Date Avg 62 Note -274p. ERRS Price MF -$125 HC-$1320 Descriptors -*Communicat;on Satellites.CommunityBenefits. CostEffectiveness.*Devdop;ng Nations. Educational Television. ElectronicEquipment. *Feasibility Studies. Med.a. Media Technology. National Heteroganeous Grouping. *Indians. Mass Demooraphy, National Programs.Production Techniques. ProgramPlanninc). Radio. Technical Assistance,*Television. Yelevision Research,World Protlems Identifiers-AIR, Air India Radio,INCOSPAR, Indian National Committee Aeronautics and Space Administration on Space Research. NASA, National India. likemany developing nations, mustsoon make a decision about satellite television. National integration. upgrading and extendingeducation. strengthening the vocational and technicalcomponents of education, modernizing planning. teaching literacy--the agriculture. family stated goals of the Indiangovernment- -could be more easily achieved witha national television network. Capital operating costs for such investment and a program are high: less expensivealternatives should be considered. An adequate technicaland personnel base wouldbe necessary for reliable service--whichmeans training programs and industrialmodernization if the country is not to be dependenton outside help. A department must be control and organize the established to program. If satellite television is to beemployed. the problems ofaccess to satellite technology,coverage area ar,d spillover. and heterogeneity of the viewing audiencemust be solved. It is probable that.in the case of India. the bestway to provide an economical. reliable.national network, with service to the villages, isto move gradually in the directionof a system employing direct television broadcastfrom a satellite. -

Stories on Human Rights by Filmmakers, Artists and Writers

Stories on Human Rights by Filmmakers, Artists and Writers •MARINA ABRAMOVIC •CHARLES DE MEAUX •HANY ABU-ASSAD •TONI MORRISON •CHIMAMANDA NGOZI ADICHIE •MURALI NAIR •ARMAGAN BALLANTYNE •IDRISSA OUEDRAOGO •SERGEI BODROV •RUTH OZEKI •ASSIA DJEBAR •PIPILOTTI RIST •NURUDDIN FARAH •DANIELA THOMAS •DOMINIQUE GONZALEZ-FOERSTER •SAMAN SALOUR & ANGE LECCIA •JOSÉ SARAMAGO •KHALED HOSSEINI •SARKIS •RUNA ISLAM •ROBERTO SAVIANO •ELFRIEDE JELINEK •BRAM SCHOUW •FRANCESCO JODICE •TERESA SERRANO •ETGAR KERET •ABDERRAHMANE SISSAKO & SHIRA GEFFEN •PABLO TRAPERO •ZHANG-KE JIA •APICHATPONG WEERASETHAKUL •NAGUIB MAHFOUZ •MO YAN •GABRIEL GARCIA MARQUEZ •JASMILA ZBANIC Concept and Curatorship : An initiative of : A Project of : Adelina von Fürstenberg OFFICE FOR THE HIGH UNITED NATIONS COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Stories on Human Rights by Filmmakers, Artists and Writers SUMMARY The Partners p. 3 Press release p. 4 The genesis of a worldwide artistic project p. 5 A film of six themes and 22 short-movies p. 6 1 / Culture p. 7 2 / Development p. 8 3 / Dignity and Justice p. 9 4 / Environment p. 10 5 / Gender p. 11 6 / Participation p. 12 List of screenings p. 13 Stories on Human Rights, the book p. 14 History: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights p. 16 Human Rights today p. 17 ART for The World p. 18 Partners p. 19 CONTACTS Faits&Gestes : Sébastien Bizet / Laurent Delarue 10, rue des Messageries – 75010 Paris [email protected] / [email protected] 00 33 (0)1 53 34 65 84 00 33 (0)6 07 55 54 81 / 00 33 (0)6 30 25 34 66 ART for -

Analysis of the UIS International Survey on Feature Film Statistics

INFORMATION SHEET No. 1 Analysis of the UIS International Survey on Feature Film Statistics With the support of the Government of Québec and in collaboration with the Institut de la statistique du Québec (ISQ), the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) launched a new international survey in 2007 to collect data on feature films. The analysis was based on a preliminary study by Ivan Bernier, Associate Professor, Université Laval and Serge Bernier, Associate Professor, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières. Introduction The UIS International Survey on Feature Film Statistics is based on a new approach to gather internationally comparable and better quality data in the field of culture statistics. Cinema data elicit much interest because the film industry is experiencing massive transition and growth in certain developing countries. These data can also be relevant to the study of the diversity of cultural expressions. Data was obtained from 101 countries for the years 2005-2006, indicating a coverage rate of 49%. This is a relatively reasonable coverage rate for an international survey. In the majority of cases, the data were obtained directly from countries in response to the questionnaire; 75 countries responded, for a response rate of 36%. Among those who responded, 11 – mainly developing countries – indicated they had no data on film production. Data on 26 other countries were obtained from alternative sources (government information available on the Internet, international compilations, etc.). Figure 1 shows the geographical imbalance in coverage rates – a strong concentration in Europe and North America with a coverage rate of 88% and very little coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Pacific with 33%, 27% and 24% respectively. -

Sr-Hd2700u Sr-Hd2700e

BLU-RAY DISC & HDD RECORDER SR-HD2700U INSTRUCTIONS SR-HD2700E HBDD REC DER C OPEN/ CLOSE STANDBY/ON REC INPUT MEDIA SELECT DIRECT/ RESET MODE SELECT HDD BD/SD MONITOR STOP REV PLAY FWD PAUSE REC HDV/DV IN . For Customer Use: Please read the following before getting started: Enter below the Model No. and Serial No. which is located Thank you for purchasing this product. on the body. Retain this information for future reference. Before operating this unit, please read the instructions carefully to ensure the best possible performance. Model No. In this manual, each model number is described without the Serial No. last letter (U/E) which means the shipping destination. (U: for USA and Canada, E: for Europe) Only “U” models (SR-HD2700U) have been evaluated by UL. B5A-3019-00 Safety Precaution Cautions CLASS 1 LASER PRODUCT REPRODUCTION OF LABELS Safety Precaution WARNING LABEL INSIDE OF THE UNIT CAUTION AVIS RISKOF OF ELECTRIC SHOCK RISQUE DE CHOC CHOC ELECTRIQUE ELECTRIQUE DO NOTNOT OPEN OPEN - NE PAS OUVRIR.OUVRIR. CAN ICES-3 A / NMB-3 A The lightning flash with arrowhead symbol, within an equilateral triangle, is intended to alert the user to the presence of uninsulated “dangerous voltage” within the product’s enclosure that may be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle is intended to alert the user to the presence of important operating and maintenance (servicing) A B instructions in the literature accompanying the This unit apply to the standard IEC60825-1:2007 for laser products. -

African Currents Vol. 39 Issue. 2 2021

ISSN: 2394-4358 Vol. XXXIX No.2 2021 A F R I C A N In this Issue 1. Engaging Indian Religious Practices in Nigeria via C Cinematic Experience of Indian Doctor Ajetunmobi Oluwasegun U 2. Impact of Bollywood on the Development of Kannywood in Northern Nigeria Olayemi Dotun R 3. Zimbabwe-India relations: Reception of the portrayal of the relations between the countries on Zimbabwean state media R Jennings Joy Chibike 4. Deconstructing Exilic Narratives of Tibetan Refugee Community in India and Residual Liberian Refugees in E Nigeria Tosin Durodola 5. Afforestation as a means to contrast aridity and soil N degradation in Rajasthan, India and Sahel, Africa: Possible space for south-south cooperation and experience exchange between the two regions T Ilaria Petrolati 6. Indian NGOs and Organizations Working for the Siddi Community S Jyoti Ravishankar Singh Centre for African Studies, University of Mumbai Editorial Team Renu Modi (Professor and Director, CAS) Meera Venkatachalam (Post-doctoral Research Fellow, CAS) Neda Shaikh (Research Assistant, CAS) Johann Salazar (Independent Researcher) Layout design and cover photo Johann Salazar Editor’s Note This issue of African Currents is comprised of a selection paper, submitted as part of the International Online Internship programme organised by the Centre of African Studies, that study similarities and differences between peoples and cultures of India and Africa. It is these similarities that can pave the way for future co-operation and these differences that provide unique learning opportunities for the other. Media such as films and TV have provided portal through which the other can be explored. -

EMERGING MARKETS and the DIGITALIZATION of the FILM INDUSTRY an Analysis of the 2012 UIS International Survey of Feature Film Statistics

UIS INFORMATION PAPER NO. 14 AUGUST 2013 EMERGING MARKETS AND THE DIGITALIZATION OF THE FILM INDUSTRY An analysis of the 2012 UIS International Survey of Feature Film Statistics UNESCO The constitution of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was adopted by 20 countries at the London Conference in November 1945 and entered into effect on 4 November 1946. The Organization currently has 195 Member States and 8 Associate Members. The main objective of UNESCO is to contribute to peace and security in the world by promoting collaboration among nations through education, science, culture and communication in order to foster universal respect for justice, the rule of law, and the human rights and fundamental freedoms that are affirmed for the peoples of the world, without distinction of race, sex, language or religion, by the Charter of the United Nations. To fulfil its mandate, UNESCO performs five principal functions: 1) prospective studies on education, science, culture and communication for tomorrow's world; 2) the advancement, transfer and sharing of knowledge through research, training and teaching activities; 3) standard-setting actions for the preparation and adoption of internal instruments and statutory recommendations; 4) expertise through technical co-operation to Member States for their development policies and projects; and 5) the exchange of specialized information. UNESCO is headquartered in Paris, France. UNESCO Institute for Statistics The UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) is the statistical office of UNESCO and is the UN depository for global statistics in the fields of education, science and technology, culture and communication. The UIS was established in 1999. -

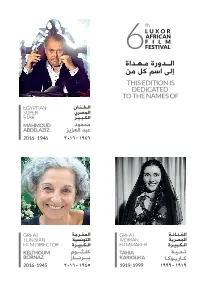

ﺍﻝــﺛﻭﺭﺓ ﻄـﻋـﺛﺍﺓ ﺇﻝﻯ ﺍﺠﻃ ﺾﻀ ﻄﻆ This Edition Is Dedicated to the Names Of

th LUXOR AFRICAN FILM 6FESTIVAL ﺍﻝــﺛﻭﺭﺓ ﻄـﻋـﺛﺍﺓ ﺇﻝﻯ ﺍﺠﻃ ﺾﻀ ﻄﻆ THIS EDITION IS DEDICATED TO THE NAMES OF ﺍﻝـﻑـﻈـﺍﻥ EGYPTIAN ﺍﻝﻡﺧﺭﻱ SUPER ﺍﻝﺿـﺊـﻐـﺭ STAR ﻄﺗﻡﻌﺩ MAHMOUD ﺲﺊﺛ ﺍﻝﺳﺞﻏﺞ ABDELAZIZ ١٩٤٦ - ٢٠١٦ 1946 - 2016 ﺍﻝﻑـﻈـﺍﻇـﺋ GREAT ﺍﻝﻡﺚـﺭﺝﺋ GREAT ﺍﻝﻡﺧﺭﻏﺋ IVORIAN ﺍﻝﺎﻌﻇﺱﻐﺋ TUNISIAN ﺍﻝـﺿـﺊﻐـﺭﺓ FILMMAKER ﺍﻝـﺿـﺊﻐـﺭﺓ FILM DIRECTOR ﺕـﺗـﻐـﺋ TAHIA ﺾﻂـﺑـــﻌﻡ KELTHOUM ﺾـﺍﺭﻏـﻌﺾـﺍ KARIOUKA ﺏـــﺭﻇـــﺍﺯ BORNAZ ١٩١٩ - ١٩٩٩ 1999 1919- ١٩٤٥ - ٢٠١٦ -1945 2016 ﺖﻂﻡﻎ ﺍﻝﻈﻡﻈﻃ ﻭﺯﻏﺭ ﺍﻝﺑﺼﺍﺸﺋ MINISTER OF CULTURE HELMY AL NAMNAM ﺗﺄﺗﻲ اﻟﺪورة اﻟﺴﺎدﺳﺔ ﻟﻬﺬا اﻟﻤﻬﺮﺟﺎن، ﻓﻲ ﻇﻞ ﻣﻨﻌﻄﻒ ﺟﺪﻳﺪ، إﻳﺠﺎﺑﻲ وﻣﻬﻢ، ﺗﺸﻬﺪه ﻣﺼﺮ، ﺣﻴﺚ ﺻﺎر اﻻﻫﺘﻤﺎم ﺑﺎﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ -ﻋﻤﻮﻣ -ﻣﻦ أوﻟﻮﻳﺎت اﻟﺤﻜﻮﻣﺔ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ، ارﺗﻔﻌﺖ اﻟﻤﻴﺰاﻧﻴﺔ اﻟﻤﺨﺼﺼﺔ ﻟﺼﻨﺪوق دﻋﻢ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ، ﻣﻦ ٢٠ ﻣﻠﻴﻮن ﺟﻨﻴﺔ إﻟﻰ ٥٠ ﻣﻠﻴﻮن ﺟﻨﻴﺔ ﺳﻨﻮﻳ، وﻳﺠﺮي اﻟﻌﻤﻞ ﺑﺠﺪﻳﺔ ﻟﺘﺄﺳﻴﺲ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺗﻴﻚ، وﺗﺄﺳﻴﺲ ﺷﺮﻛﺔ ﻗﺎﺑﻀﺔ ﻟﻧﺘﺎج اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺋﻲ، ﻣﻤﺎ ٌﻳﺒﺸﺮ ﺑﺈزدﻫﺎر ﺣﻘﻴﻘﻲ ﻟﺼﻨﺎﻋﺔ اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎ، وﻓﻀﻼً ﻋﻦ ذﻟﻚ، ﻓﺈن ا¨ﻧﺘﺎج اﻟﺴﻴﻨﻤﺎﺋﻲ اﻟﻤﺼﺮي، ﺷﻬﺪ ﺧﻼل اﻟﻌﺎم اﻟﻤﻨﺼﺮم ارﺗﻔﺎﻋ ﻓﻲ أﻋﺪاد ا³ﻓﻼم اﻟﺘﻲ ﺗﻢ إﻧﺘﺎﺟﻬﺎ، وﺗﻤﻴﺰ· ﻓﻲ اﻟﻤﺴﺘﻮى اﻟﻔﻨﻲ. ﺗﺄﺗﻲ ﻫﺬه اﻟﺪورة -ﻛﺬﻟﻚ -ﻓﻲ ﻇﻞ اﻫﺘﻤﺎم اﻟﺪوﻟﺔ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ ﺑﺘﻨﺸﻴﻂ وﺗﻌﻤﻴﻖ اﻟﻌﻼﻗﺎت اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ -ا³ﻓﺮﻳﻘﻴﺔ، ودﻋﺎ اﻟﺮﺋﻴﺲ ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻔﺘﺎح اﻟﺴﻴﺴﻲ ﻓﻲ ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ ﻣﺆﺗﻤﺮ أﺳﻮان ﻟﻠﺸﺒﺎب، إﻟﻰ إﻋﺪاد أﺳﻮان ﻟﺘﻜﻮن ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻗﺘﺼﺎد واﻟﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ ا¨ﻓﺮﻳﻘﻴﺔ. وأﺧﻴﺮ·، ﺗﺘﻮاﻓﻖ ﻫﺬه اﻟﺪورة ﻣﻦ اﻟﻤﻬﺮﺟﺎن، ﻣﻊ اﻻﺣﺘﻔﺎل ﺑﺎ³ﻗﺼﺮ ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻠﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ، ﻃﻮال ﻫﺬا اﻟﻌﺎم، ﻛﺎﻧﺖ ا³ﻗﺼﺮ داﺋﻤ ﻧﻘﻄﺔ اﻟﺘﻘﺎء ﺑﻴﻦ اﻟﺤﻀﺎرﺗﻴﻦ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﻳﺔ اﻟﻘﺪﻳﻤﺔ (اﻟﻔﺮﻋﻮﻧﻴﺔ) واﻟﺤﻀﺎرة اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ – ا¨ﺳﻼﻣﻴﺔ، واﺧﺘﻴﺎر ا³ﻗﺼﺮ ﻋﺎﺻﻤﺔ ﻟﻠﺜﻘﺎﻓﺔ اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ، ﻳﺆﻛﺪ ﻋﻠﻰ ﻫﺬا ٌاﻟﺒﻌﺪ. The sixth edition of Luxor African Film Festival comes within the shadow of a new positive and significant turn that Egypt is witnessing of paying a special attention to cinema and being one of the priorities of the Egyptian government as the budget of the cinema fund has increased from 20 million EGP to 50 million EGP annually, while tireless efforts are made to found Cimatheque and founding a company for cinema production that promises a rich cinema production in addition to the increase of the number of produced films last year and of a good quality.