First Ascent of the Galenstock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Switzerland. Design &

SWITZERLAND. DESIGN & LIFESTYLE HOTELS Design & Lifestyle Hotels 2021. Design & Lifestyle Hotels at a glance. Switzerland is a small country with great variety; its Design & Lifestyle Hotels are just as diverse. This map shows their locations at a glance. A Aargau D Schaffhausen B B o d Basel Region e n s Rhein Thur e 1 2 e C 3 Töss Frauenfeld Bern 29 Limm B at Baden D Fribourg Region Liestal 39 irs B Aarau 40 41 42 43 44 45 Herisau Delémont 46 E Geneva A F Appenzell in Re e h u R H ss 38 Z ü Säntis r F Lake Geneva Region i 2502 s Solothurn c ub h - s e o e D e L Zug Z 2306 u g Churfirsten Aare e Vaduz G r W Graubünden 28 s a e La Chaux- e lense 1607 e L i de-Fonds Chasseral e n e s 1899 t r 24 25 1798 h le ie Weggis Grosser Mythen H Jura & Three-Lakes B 26 27 Rigi Glarus Vierwald- Glärnisch 1408 Schwyz Bad Ragaz 2119 2914 Neuchâtel re Napf stättersee Pizol Aa Pilatus Stoos Braunwald 2844 l 4 I Lucerne-Lake Lucerne Region te Stans La 5 nd châ qu u C Sarnen 1898 Altdorf Linthal art Ne Stanserhorn R Chur 2834 de e Flims J ac u 16 Weissfluh Piz Buin Eastern Switzerland / L 2350 s Davos 3312 18 E Engelberg s mm Brienzer Tödi e Rothorn 14 15 Scuol Liechtenstein e 12 y Titlis 3614 17 Arosa ro Fribourg 7 Thun 3238 Inn Yverdon B Brienz a D 8 Disentis/ Lenzerheide- L r s. -

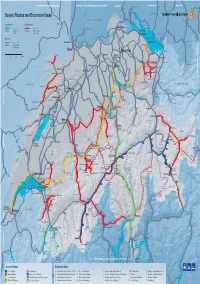

Scenic Routes and Excursion Ideas +

Strasbourg | Luxembourg | Bruxelles Karlsruhe | Frankfurt | Dortmund | Hamburg | Berlin Stuttgart Ulm | München München + + Stockach Engen Ravensburg Scenic Routes and Excursion Ideas + +Singen DEUTSCHLAND Kempten + Mulhouse + Scenic Routes Excursion Ideas + Insel Mainau A–T + Schaffhausen + + 1– 8 + ++ Meersburg + Zell (Wiesental) Railways Buses, Railways Buses, Boats, + Konstanz + + Boats Cable cars Kreuzlingen Friedrichshafen Other lines + Bodensee + + Immenstadt + + EuroAirport + Romanshorn + Railways Buses, Boats, + Lindau Cable cars Basel + +Winterthur Bregenz + Baden + Bonfol Zürich + 0102030km + +Flughafen St.Margrethen P + + Porrentruy Gossau + + St.Gallen Dornbirn + Aarau S + Oberstdorf + + Zürich Herisau Gais + + Altstätten SG + Delémont + T S Passwang + S Olten o + Appenzell Glovelier + g + g 8 e Urnäsch + S Innsbruck | Salzburg | Wien P n Weissenstein + b Wasserauen + s u + + n e r Feldkirch + g Zürich- g Schwägalp Besançon t a Säntis FRANCE n see Rapperswil ÖSTERREICH o P + n Le Noirmont + i M + Solothurn 3 s t e s Tavannes + A l p e + Bludenz h + c + Zug n Buchs SG LIECHTENSTEIN Langen a.A. + + + a r Rotkreuz + Zugersee Vaduz Arlberg St.Anton P Biel/Bienne J + F + + Walensee La Chasseral Einsiedeln + La Chaux-de-Fonds + 8 Dijon | Paris Schruns Bielersee Rigi + Luzern + + +Arth-Goldau J B + Glarus Sargans + G Erlach E + Napf 4 Neuchâtel + m T h Vierwald- Landquart + m Pilatus + M e c stättersee G + n u Bern t b Pizol J + a e P l l G r N n t + ä + B E t t Lac de Murten + B Linthal + i g Pontarlier G +Flüelen a u + Klosters -

Spatial Variation in Annual Nitrogen Deposition in a Rural Region in Switzerland

Environmental Pollution 102, S1 (1998) 327–335 reformated layout similar to printed version Spatial variation in annual nitrogen deposition in a rural region in Switzerland a b a a a Werner Eugster ∗, Silvan Perego , Heinz Wanner , Alex Leuenberger , Matthias Liechti , Markus Reinhardt c , Peter Geissbühler d, Marion Gempeler a , and Jürg Schenk a a University of Bern, Institute of Geography, Hallerstrasse 12, CH-3012 Bern, Switzerland bSwiss Federal Institute of Technology, Air and Soil Pollution Laboratory, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland c Swiss Meteorological Office, Krähenbühlstrasse 58, CH-8004 Zürich, Switzerland dPaul Scherrer Institute, CH-5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland Received 27 March 1998; accepted 9 September 1998 Abstract We studied the spatial variation in annual nitrogen deposition to the Seeland region of Switzerland by combining (1) mesoscale atmospheric modeling of gaseous dry deposition, (2) wet deposition data measured within the study area as well as published data, and (3) estimates of dry deposition of aerosol particles based on concentration measurements and sedimentation samples from a near-by region. Gaseous 1 1 dry deposition shows greatest regional variation. Total nitrogen input to this region is in the range of 22–51 kg N ha− yr− (13–42 kg N gaseous dry deposition; 7–8 kg N wet deposition; 2 kg N dry deposition of aerosol particles). Gaseous dry deposition is dominated ≈ 1 1 by reduced nitrogen components from agricultural sources. The highest nitrogen inputs were found over lakes (51 kg N ha− yr− ). Our 1 1 results indicate that current nitrogen loads exceed the nutrient critical loads by several kg N ha− yr− in all nitrogen-sensitive ecosystem types occurring in our 70 50 km2 study area. -

Snow Travel Mart Switzerland. March 18 to 22, 2018 – Gstaad

Snow Travel Mart Switzerland. March 18 to 22, 2018 – Gstaad. STnet.ch/stms Contents. Welcome 3 General information 4 Switzerland Tourism Program 6 P.O. Box CH-8027 Zurich Hotels 7 [email protected] MySwitzerland.com Map of destination Gstaad 8 Cover pictures Transfer timetable 10 Gstaad Palace, Gstaad, Canton of Bern (front page) Workshop floor plan 12 Eggli, Gstaad, Supplier list 13 Canton of Bern (rear page) Host destination Gstaad 14 It is our pleasure to help plan your vacation: Swiss International Air Lines 16 00800 100 200 29 (free phone). Swiss Travel System 17 Mon–Fri 8 am to 6 pm Sat 10 am to 4 pm Switzerland 18 Notes 20 Map of Switzerland. Stuttgart 137 mi / 220 km Switzerland is a small but very Munich 162 mi / 261 km Amsterdam 375 mi / 603 km diverse country. This map shows Brussels 348 mi / 560 km G you the different tourism regions. Frankfurt 178 mi / 286 km Schaffhausen B o d e n s Rhein Thur e e Töss Frauenfeld Berlin 410 mi / 660 km im A L ma Aargau t Vienna 375 mi / 603 km Liestal Baden B Basel Region irs Aarau B B M Delémont A Herisau C Bern Appenzell in H Re e F h uss Säntis R Z Saignelégier ü 2502 D Eastern Switzerland / r i c D s Solothurn Wildhaus A ub h - s e o e D e L Zug Liechtenstein Z 2306 u LIECHTENSTEIN g Churfirsten FL Aare e r W s a ee La Chaux- e Einsiedeln lens 1607 J e L de-Fonds Chasseral i E Fribourg Region e n Malbun e s 1899 t r h Flumserberg e el Grosser Mythen Bi Weggis 1798 Glarus Rigi F C Vierwald- Glärnisch Geneva Schwyz 2914 Bad Ragaz 1408 2119 Neuchâtel e Napf stättersee Pizol Aar Pilatus Stoos 2844 Landquart l Samnaun te Braunwald La G Graubünden Stans Elm nd châ Klewenalp qu u Murten Sarnen 1898 Altdorf Linthal art Klosters Ne Stanserhorn R Chur 2834 de e Flims H ac u Weissfluh Piz Buin Jura & Three-Lakes Ste-Croix L Sörenberg 2350 s Davos 3312 E Engelberg s Tödi mm Brienzer 3614 Brigels e Rothorn Laax Scuol e y Titlis Arosa o Fribourg Inn I Lake Geneva Region r Thun Brienz Melchsee-Frutt 3238 Yverdon B a Disentis/ Lenzerheide- L rs. -

Juillet & Août 2020

Revue de presse juillet-août 2020 02.09.2020 Avenue ID: 347 Coupures: 50 Pages de suite: 54 01.07.2020 Schweizer Landliebe Schweizer Pärke - darum gehts 01 Tirage: 190'492 01.07.2020 sportmail.ch / Sport + Freizeit Mail Die Regionalparks um Biel laden zum geniessen ein 06 01.07.2020 canalalpha.ch / Canal Alpha Online L'agriculture et la biodiversité au coeur de la stratégie 08 03.07.2020 journaldujura.ch / Journal du Jura Online Fruit du travail des élèves arboriculteurs dévoilé 09 04.07.2020 journaldujura.ch / Journal du Jura Online Fruit du travail des élèves arboriculteurs dévoilé 11 04.07.2020 RTN - Radio Neuchâtel / Le journal 18.00 | Durée: 00:01:53 Une empreinte verte pour les écoliers du Parc Chasseral 13 06.07.2020 Journal du Jura Un an d'activités avec le Parc pour 380 graines de chercheurs 14 Tirage: 8'408 03.07.2020 Feuille d'avis du District de Courtelary A la découverte des plantes médicinales ou des météorites 16 Tirage: 12'000 09.07.2020 Terre & Nature / Hors-Série Agritourisme CAP SUR LES PARCS NATURELS DE SUISSE! 18 Tirage: 30'000 09.07.2020 rjb.ch / Radio Jura Bernois Online La Combe-Grède trop cotée? 28 10.07.2020 L'Echo du Gros-de-Vaud Un an d'activités avec le Parc pour 380 Graines de chercheurs 29 Tirage: 3'135 10.07.2020 Agri A la recherche de solutions pour mieux intégrer les agriculteurs dans les parcs 31 Tirage: 9'279 11.07.2020 Smart Media im Tages-Anzeiger Themenbeilage Mit dem E-Bike kleine Weltwunder erleben 35 Tirage: 130'957 11.07.2020 Schweizer Bauer Agrotourismus SCHWEIZER PÄRKE: IN EINER EINMALIGEN LANDSCHAFT -

10507 PRC Cartes Postales.Qxp 9.2.2008 12:16 Page 1

10507_PRC_cartes postales.qxp 9.2.2008 12:16 Page 1 1 Sentier de la crête de Chasseral Der Gratweg auf dem Chasseral 13 points d’observation commentés pour comprendre la végétation, la faune et le paysage. 13 Besichtigungsposten mit Erklärungen zu Vegetation, Tierwelt und Landschaft. 10507_PRC_cartes postales.qxp 9.2.2008 12:16 Page 2 2 Sentier de la crête / Gratweg Sommaire / Inhalt Introduction p.3 Les plantes, médecine d'antan pp. 39-42 Einleitung Heilpflanzen, die Medizin früherer Zeiten Une étude pour protéger efficacement la flore sommitale de Chasseral p.4 La flore de Chasseral, témoin des glaciations pp. 43-46 Eine Studie zum wirkungsvollen Schutz der Bergplanzen auf dem Chasseral Die Flora des Chasserals, Zeugin der Eiszeit Richesse en plantes remarquables sur le sommet de Chasseral p.5 Forêt ouverte, refuge d'espèces rares pp. 47-50 Grosser Reichtum an beachtenswerten Pflanzen auf dem Chasseralgipfel Offener Wald, Zufluchtsort für seltene Arten Présentation du sentier de la crête de Chasseral p.6 Pauvreté du sol, richesse des plantes pp. 51-54 Beschreibung des Chasseral-Gratwegs Karger Boden, vielfältige Pflanzen Hautes altitudes, plantes basses pp. 7-10 Le paysage, action de l’homme pp. 55-58 Grosse Höhen, kleine Pflanzen Eine durch Menschenhand geprägte Landschaft Les dolines, ouverture vers un monde souterrain pp. 11-14 Carte postale «Hôtel Chasseral» p.59 Die Dolinen, Türen zur unterirdischen Welt Postkarte «Hotel Chasseral» L’été au Chasseral, l’hiver en Afrique! pp. 15-18 Carte postale «panorama des Alpes» p.61 Im Sommer auf dem Chasseral, im Winter in Afrika! Postkarte «Alpenpanorama» Plantes et papillons, des inséparables pp. -

The Grenchenberg Conundrum in the Swiss Jura: a Case for the Centenary of the Thin-Skin Décollement Nappe Model (Buxtorf 1907)

1661-8726/08/010041–20 Swiss J. Geosci. 101 (2008) 41–60 DOI 10.1007/s00015-008-1248-2 Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, 2008 The Grenchenberg conundrum in the Swiss Jura: a case for the centenary of the thin-skin décollement nappe model (Buxtorf 1907) HANS LAUBSCHER Key words: Jura, décollement, Grenchenberg tunnel, asperities, reactivation, collision ABSTRACT ZUSAMMENFASSUNG When Buxtorf in 1907 proposed his décollement hypothesis which visualized Als Buxtorf 1907 seine Abscherungshypothese vorstellte, in der der Faltenjura the Jura fold belt as a “folded décollement nappe” pushed by the Alps, he met als eine von den Alpen her geschobene „gefaltete Abscherdecke“ konzipiert with both fervent support of a few and skepticism by the many. As an illustra- war, stiess er bei Wenigen auf begeisterte Zustimmung; die Mehrheit blieb tion of recalcitrant problems within the Jura décollement nappe, that remain skeptisch. Um zu illustrieren, dass es auch heute noch, nach hundert Jahren, after 100 years, a model of the Grenchenberg complex is presented within widerspenstige Probleme im abgescherten Jura gibt, wird unter Verwendung the frame of 3D décollement kinematics, based on a set of rules gleaned from einer Anzahl von Regeln der Versuch unternommen, ein 3D-kinematisches recurrent features in the Jura: (1) that generally progression of décollement Abschermodell des Grenchenberg-Komplexes zu entwickeln. Die Regeln sind was in sequence from south to north, (2) that in any given structure thrusting (1) dass generell (d. h. mit Ausnahmen) Abscherung und Faltenbildung -

Totally4bikers 2020 EXCEPTIONAL RIDES…

totally4bikers 2020 EXCEPTIONAL RIDES… Remember… It’s not the Destination… It's the journey that counts… 2020 - EXCEPTIONAL RIDES – 3 Tours in 1… Wednesday 17th June – Sunday 28th June 2020 Ardennes - Vosges - Switzerland 5 Passes - WW1 Memorials… totally4bikers “Exceptional Rides” have been specifically designed to meet the demands and needs of Bikers looking for quality and safe Biking roads taking in places of interest supported by high quality 3 & 4-Star Hotel accommodation and locations. Following the success of our 2017/2018 & 2019 Tours & events, which we ran alongside a number of Motorcycle Dealerships, we are pleased to announce that for 2020 DUNLOP TYRES and BIKE SEAL are our sponsors. O ver the past 3 years it has become increasingly evident that a large majority of clients are looking for something dare we say “Better Organised” and more “Up Market” than your average UK/Overseas B&B Tour. So for 2020 we have once again collated our “Exceptional Rides Experience” offering our attained high standard planned routes along superb quality 3 & 4-Star Hotels whilst riding through areas of outstanding natural beauty accompanied by some of the most fantastic roads & scenery In Europe. As with all our “Exceptional Rides Tours” we have focused on collating places of interest and routes to specifically attract riders who ride safe and legal with a level of sensible and experienced riding skills at the same time encouraging both Male & Female Riders including Riders and Pillions. Day 1 – Wednesday 17th – Folkestone…. Where do we start???... Well It’s a known fact that traveling down to the Eurotunnel in Folkestone is not the most exciting of journeys and therefore we have planned for all participants to meet up the night before at the Holiday Inn Hotel Folkestone, thus allowing a fresh start to the Exceptional Rides Tour the following morning. -

Plan Directeur Du Canton De Berne

Plan directeur du canton de Berne Plan directeur 2030 Etat : 11 janvier 2021 Conseil-exécutif du canton de Berne Impressum Edition: Conseil-exécutif du canton de Berne Etat: Mise à jour du plan directeur en 2020 (Décision de la DIJ du 2 séptembre 2020) La version actuelle du plan directeur cantonal est disponible sur Internet à l’adresse www.be.ch/plandirecteur. Le site permet également d’accéder au système d’information du plan directeur (application cartographique en ligne) et propose des fonctions de recherche étendues. Distribution: Office des affaires communales et de l’organisation du territoire Nydeggasse 11/13 3011 Berne Téléphone 031 633 77 30 http://www.be.ch/plandirecteur Numéro de commande: 02.01 f Table des matières Table des matières Introduction Les objectifs du Conseil-exécutif concernant le plan directeur 1 Possibilités d'action dans le domaine de l'aménagement du territoire cantonal 4 La portée du plan directeur cantonal 5 La structure du plan directeur cantonal 6 Répercussions juridiques du plan directeur cantonal 8 Révision du plan directeur 9 Projet de territoire du canton de Berne Portée et contenu du projet de territoire 1 Aménagement du territoire: quels défis? 2 Les orientations générales du développement cantonal 5 Les objectifs principaux du développement territorial du canton de Berne 7 Objectifs principaux de nature thématique 7 Objectifs principaux de nature spatiale 10 Objectifs principaux de nature organisationnelle 13 Stratégies Chapitre A: Utiliser le sol avec mesure et concentrer l’urbanisation A1: Stratégie -

Switzerland Travel Mart. October 20–23, 2019, Lucerne

Switzerland Travel Mart. October 20–23, 2019, Lucerne. MySwitzerland.com Contents. Welcome 3 General information 4 Switzerland Tourism Program 6 P. O. Box CH-8027 Zurich Map of Lucerne 8 [email protected] MySwitzerland.com Hotels 10 Cover pictures Workshop floor plan 12 Lucerne (front page) Pilatus (rear page) Switzerland 14 Lucerne-Lake Lucerne Region 16 It is our pleasure to help plan your holiday: Swiss International Air Lines 18 00800 100 200 30 (free phone). Swiss Travel System 19 Mon–Fri 8 am to 6 pm Sat 10 am to 4 pm Notes 20 Map of Switzerland. Switzerland is a small but very Amsterdam 375 miles / 603 km diverse country. This map shows Brussels 348 miles / 560 km you the different tourism regions. Frankfurt 178 miles / 286 km Schaffhausen B o d e n s Rhein Thur e e Töss Frauenfeld Limma A Aargau t Liestal Baden B Basel Region irs Aarau B B Delémont Herisau C Bern Appenzell in H Re e h uss R Z Säntis ü D Eastern Switzerland / r 2502 i c s Solothurn ub h - s e o e D e L Zug Z 2306 Liechtenstein u g Churfirsten Aare e Vaduz r W s a e La Chaux- 1607 e lense e L LIECHTENSTEIN Chasseral i E Fribourg Region de-Fonds e n e s 1899 t r h e el Grosser Mythen Bi Weggis 1798 Glarus Rigi F Vierwald- Glärnisch Geneva C 1408 Schwyz Bad Ragaz 2119 2914 Neuchâtel re Napf stättersee Pizol Aa Pilatus Stoos Braunwald 2844 l te Stans La G Graubünden nd châ qu u Sarnen 1898 Altdorf Linthal art Ne Stanserhorn R Chur 2834 de e Flims u Piz Buin H Jura & Three-Lakes ac Weissfluh L 2350 s Davos 3312 E Engelberg s mm Brienzer Tödi e Rothorn Scuol e y Titlis 3614 Arosa o Fribourg Inn I Lake Geneva Region r Thun Brienz 3238 Yverdon B a Disentis/ Lenzerheide- L rs. -

Grand Tour of Switzerland Is a Suggested Route That Makes Use of the Existing Swiss Road Network

SWITZERLAND. GRAND TOUR THE NO. 1 ROAD TRIP OF THE ALPS MORE THAN 995 REASONS TO DISCOVER SWITZERLAND ON THE GRAND TOUR: Extreme fun around winding bends: 5 Alpine passes higher than 2,000 m Tons of fresh water: 22 lakes larger than 0.5 km² Schaffhausen Multicultural society: 4 national languages, numerous dialects B o World-class road signs: 650 official Grand Tour signposts d e n First electric road trip: more than 300 charging stations for electric vehicles s Rhein Thur e e Outstanding highlights: 12 UNESCO World Heritage sites and 2 Biosphere Reserves Töss Frauenfeld Limma 1 Abbey of St. Gallen t 2 Swiss Tectonic Arena Sardona Liestal Baden irs Aarau 3 Benedictine Convent of St. John at Müstair B Delémont Herisau 4 Biosfera Engiadina Val Müstair Appenzell in Re e h u R 5 Rhaetian Railway in the FRANCE ss Z ü Säntis Albula / Bernina landscapes r 2502 i c s Solothurn ub h - s e o e D 6 The Three Castles of Bellinzona e L Zug Z 2306 u g Churfirsten Aare e Vaduz r W 7 Monte San Giorgio s a e La Chaux- 1607 e lense e L Chasseral i de-Fonds e n 12 e t 8 Swiss Alps Jungfrau-Aletsch s 1899 r h e el Grosser Mythen Bi Weggis 1798 Glarus 9 The Architectural Work of Le Corbusier Rigi 11 Vierwald- Glärnisch 1408 Schwyz Bad Ragaz 14 2119 2914 10 Lavaux Vineyard Terraces Neuchâtel re Napf stättersee Pizol Aa Pilatus Stoos Braunwald 2844 l te Stans La 11 Prehistoric Pile Dwellings around 13 nd châ qu u Sarnen 1898 Altdorf Linthal art the Alps: Laténium Museum Ne Stanserhorn R Chur 2834 de e Flims ac u Weissfluh Piz Buin 12 La Chaux-de-Fonds / Le Locle, L 2350 s Davos 3312 E Engelberg s mm Brienzer Tödi e Rothorn Scuol Watchmaking Town Planning e y Titlis 3614 Arosa 2383 ro Fribourg Thun Brienz 3238 Inn Yverdon B Lenzerheide- F 13 Old City of Bern a Disentis/ L rs. -

The Hydrology of Switzerland Selected Aspects and Results

The Hydrology of Switzerland Selected aspects and results M. Spreafi co and R. Weingartner Berichte des BWG, Serie Wasser – Rapports de l’OFEG, Série Eaux – Rapporti dell’UFAEG, Serie Acque – Reports of the FOWG, Water Series No. 7 – Berne 2005 Eidgenössisches Departement für Umwelt, Verkehr, Energie und Kommunikation Département fédéral de l’environnement, des transports, de l’énergie et de la communication Dipartamento federale dell’ambiente, dei trasporti, dell’energia e delle comunicazioni Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications The Hydrology of Switzerland Selected aspects and results M. Spreafi co and R. Weingartner Berichte des BWG, Serie Wasser – Rapports de l’OFEG, Série Eaux – Rapporti dell’UFAEG, Serie Acque – Reports of the FOWG, Water Series No. 7 – Berne 2005 With contributions from: M. Auer, Ch. Graf, A. Grasso, Ch. Hegg, A. Jakob, A. Kääb, Ch. Könitzer, Ch. Lehmann, R. Lukes, M. Maisch, R. Meister, F. Paul, T. Reist, B. Schädler, M. Spreafi co, J.-P. Tripet, R. Weingartner Editors Reviewers M. Spreafico, FOWG M. Barben, FOWG R. Weingartner, GIUB N. Bischof, SLF Ch. Bonnard, EPFL Coordinator A. Gautschi, Nagra N. Goldscheider, CHYN T. Reist, GIUB D. Grebner, IACETH J. Gurtz, IACETH Authors D. Hartmann, SAEFL F. Hauser, GIUB Chapter 1 Ch. Hegg, WSL M. Spreafico, FOWG; R. Weingartner, GIUB P. Heitzmann, FOWG T. Herold, FOWG Chapter 2 A. Jakob, FOWG T. Reist, GIUB; R. Weingartner, GIUB R. Kozel, FOWG Ch. Lehmann, H – W Chapter 3 Ch. Lienhard, MHNG M. Auer, SLF; A. Kääb, GIUZ; Ch. Könitzer, GIUB; M. Maisch, GIUZ; M. Maisch, GIUZ R. Meister, SLF; F. Paul, GIUZ Ch.