RACING SCHOONERS and AMERICA's CUP DREAMS. In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Team Portraits Emirates Team New Zealand - Defender

TEAM PORTRAITS EMIRATES TEAM NEW ZEALAND - DEFENDER PETER BURLING - SKIPPER AND BLAIR TUKE - FLIGHT CONTROL NATIONALITY New Zealand HELMSMAN HOME TOWN Kerikeri NATIONALITY New Zealand AGE 31 HOME TOWN Tauranga HEIGHT 181cm AGE 29 WEIGHT 78kg HEIGHT 187cm WEIGHT 82kg CAREER HIGHLIGHTS − 2012 Olympics, London- Silver medal 49er CAREER HIGHLIGHTS − 2016 Olympics, Rio- Gold medal 49er − 2012 Olympics, London- Silver medal 49er − 6x 49er World Champions − 2016 Olympics, Rio- Gold medal 49er − America’s Cup winner 2017 with ETNZ − 6x 49er World Champions − 2nd- 2017/18 Volvo Ocean Race − America’s Cup winner 2017 with ETNZ − 2nd- 2014 A class World Champs − 3rd- 2018 A class World Champs PATHWAY TO AMERICA’S CUP Red Bull Youth America’s Cup winner with NZL Sailing Team and 49er Sailing pre 2013. PATHWAY TO AMERICA’S CUP Red Bull Youth America’s Cup winner with NZL AMERICA’S CUP CAREER Sailing Team and 49er Sailing pre 2013. Joined team in 2013. AMERICA’S CUP CAREER DEFINING MOMENT IN CAREER Joined ETNZ at the end of 2013 after the America’s Cup in San Francisco. Flight controller and Cyclor Olympic success. at the 35th America’s Cup in Bermuda. PEOPLE WHO HAVE INFLUENCED YOU DEFINING MOMENT IN CAREER Too hard to name one, and Kiwi excelling on the Silver medal at the 2012 Summer Olympics in world stage. London. PERSONAL INTERESTS PEOPLE WHO HAVE INFLUENCED YOU Diving, surfing , mountain biking, conservation, etc. Family, friends and anyone who pushes them- selves/the boundaries in their given field. INSTAGRAM PROFILE NAME @peteburling Especially Kiwis who represent NZ and excel on the world stage. -

Media Release, March 11, 2021 the America's Cup World Series (ACWS

maxon precision motors, inc. 125 Dever Drive Taunton, MA 02780 Phone: 508-677-0520 [email protected] www.maxongroup.us Media release, March 11, 2021 The America’s Cup World Series (ACWS) in December and Prada Cup in January-February were the first time that the AC75 class yachts had been sailed in competition anywhere, including by the competitors themselves. The boat’s capabilities were on full display demonstrating how hard each team has pushed the frontiers of technology, design, and innovation. Over the course of the ACWS, Emirates Team New Zealand was able to observe their competition including current challenger, Luna Rossa Prada Pirelli. Luna Rossa last won the challenger selection series back in 2000 on their first attempt at the America’s Cup. This was the last time Emirates Team New Zealand met the Italians. As history shows Italy has not yet won the cup itself. They look strong and were totally dominant in the Prada Cup Final maintaining quiet confidence, but they are up against a sailing team in Emirates Team New Zealand who are knowledgeable, skilled, and very fast. Emirates Team New Zealand will have collected a great deal of data from Luna Rossa’s racing to date, with which to compare their performance and gain valuable insight into their opponents’ tactics and strategy. The Kiwis approach to the America’s Cup campaign holds a firm focus on innovation. Back in 2017/2018 when the design process began for the new current class of AC75 yachts, the entire concept was proven only through use of a simulator without any prototypes. -

An Update on Waldo Lake Columbia Seaplane Pilots Association

Columbia Seaplane Pilots Association 13200 Fielding Road President ARON FAEGRE 503-222-2546 Lake Oswego, Oregon 97034 Vice President BILL WAINWRIGHT 503-293-7627 Treasurer JAMIE GREENE 503-292-1495 Secretary JOHN CHLOPEK 503-810-7690 March 2009 Volume 30, Issue 1 CSPA An Update on Waldo Lake e-BULL-A-TON By Aron Faegre Inside this issue: As of a month ago both Stewart and federal government owns the lake. CSPA have each filed requests for sum- Cloran filed a brief with all the reasons President’s Message mary judgments with the court asking why the case should go on and not An Update on Waldo Lake 1-2 the judge to make his ruling. This is be- stop, and attached the Carrier affida- By Aron Faegre cause we feel the record strongly sup- vit. The judge said let’s have a confer- ports a finding that Waldo Lake is navi- Jamie Greene, making us proud. 3 ence call with all parties and talk gable, which means the Forest Service about it on Tuesday (before the The TSA Proposed LASP, and (FS) is not the agency allowed to regu- planned Friday meeting). At the con- “Playbook” Operations: An Opinion 3-5 from the Alaskan Experimental Air- late seaplane use of the lake. If the lake ference call there was extensive dis- craft Association. is navigable, it is owned by the State of cussion, following which the judge Watercraft Border Crossing Oregon, and it is the State that is al- said “no.” He said he wanted to have 6 By “Chuck I-Am-a-Boat” Jarecki lowed to regulate seaplane use. -

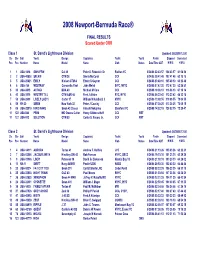

ORR Results Printout

2008 Newport-Bermuda Race® FINAL RESULTS Scored Under ORR Class 1 St. David's Lighthouse Division Updated: 06/28/08 12:00 Cls Div Sail Yacht Design Captain(s) Yacht Yacht Finish Elapsed Corrected Pos Pos Number Name Model Name Club Status Date/Time ADT H M S H M S 1 1 USA-1818 SINN FEIN Cal 40 Peter S. Rebovich Sr. Raritan YC 6/24/08 22:43:57 104 43 57 61 06 38 2 2 USA-40808 SELKIE CTM 38 Sheila McCurdy CCA 6/24/08 20:41:48 102 41 48 62 10 18 3 5 USA-20621 EMILY Nielsen CTM 44 Edwin S Gaynor CCA 6/24/08 23:48:10 105 48 10 63 23 48 4 6 USA-754 WESTRAY Concordia Yawl John Melvin IHYC, NYYC 6/25/08 07:47:20 113 47 20 63 25 51 5 30 USA-3815 ACTAEA BDA 40 Michael M Cone CCA 6/25/08 10:36:13 116 36 13 67 18 14 6 43 USA-3519 WESTER TILL CTM A&R 48 Fred J Atkins EYC, NYYC 6/25/08 06:22:42 112 22 42 68 32 18 7 58 USA-2600 LIVELY LADY II Carter 37 William N Hubbard, III NYYC 6/25/08 13:08:55 119 08 55 70 04 55 8 59 NY-20 SIREN New York 32 Peter J Cassidy CCA 6/25/08 07:38:25 113 38 25 70 05 15 9 86 USA-32510 HIRO MARU Swan 43 Classic Hiroshi Nakajima Stamford YC 6/25/08 14:02:15 120 02 15 73 25 47 11 122 USA-844 PRIM MO Owens Cutter Henry Gibbons-Neff CCA RET 11 122 USA-913 SOLUTION CTM 50 Carter S. -

Fall 2012 “Caldwell Hart Colt, The

C"3d**1& &{ar& Crltt Yk* kf.arau Tk* k{wu&ery IrKu Eo!,o *lJorll F{ast Colt was the only surviving child New York Herald newspaper, who in 1870 had defended of Sam and Elizabeth Hart Colt (Figure 1). Two the America's cup. Continually pampered by hls mother sisters and another brother were born but did not after his father died tn 1862, Caldwell's 21st birrhday parry survive. That was reason enough for his parents ro spoil was a lavish af{air for nine hundred guests, among them him, for that is what they did in every way possible. But Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) and former Connecticut as is the usual case, a spoiled child makes an irresponsible Governor James Hawley, who was a friend of Sam's. In adult, and Caldwell proved the adage "Spare the rod and the collection of this author is also a deluxe mint factory spoil the child." engraved Colt Model 1877 in nickel with ivory grips that Born at Hartford, Connecticut, on November 24, 1858, was shipped to Governor Hawley as well as several Civil presentations Caldwell was left early to the care of his mother after Sam's War were, including a well known cased set 1860 models (Wilson premature death at age 47 in 1862 when the boy was only of Colt Army 1985:103,136,168). 4 years old. His parents named him Caldwell after Sam's mother's family and Hart was from Elizabeth Colt's mother's family. According to Colt family biographer William Hosley: "Caldwell was no freak. -

Download Our 2021-22 Media Pack

formerly Scuttlebutt Europe 2021-22 1 Contents Pages 3 – 9 Seahorse Magazine 3 Why Seahorse 4 Display (Rates and Copy Dates) 5 Technical Briefing 6 Directory 7 Brokerage 8 Race Calendar 9 New Boats Enhanced Entry Page 10 “Planet Sail” On Course show Page 11 Sailing Anarchy Page 12 EuroSail News Page 13 Yacht Racing Life Page 14 Seahorse Website Graeme Beeson – Advertising Manager Tel: +44 (0)1590 671899 Email: [email protected] Skype: graemebeeson 2 Why Seahorse? Massive Authority and Influence 17,000 circulation 27% SUBS 4% APP Seahorse is written by the finest minds 14% ROW & RETAIL DIGITAL PRINT and biggest names of the performance 5,000 22% UK 28% IRC sailing world. 4,000 EUROPE 12% USA 3,000 International Exclusive Importance Political Our writers are industry pro's ahead of and Reach Recognition 2,000 journalists - ensuring Seahorse is the EUROPE A UK S UK 1,000 EUROPE U 14% RORC last word in authority and influence. ROW A A S ROW UK S ROW U 0 U ROW EUROPE IRC ORC RORC SUBS & APP 52% EUROPE (Ex UK) 27% ORC Seahorse is written assuming a high RETAIL SUBS level of sailing knowledge from it's The only sailing magazine, written Recognised by the RORC, IRC & from no national perspective, entirely ORC all of whom subscribe all readership - targetting owners and dedicated to sailboat racing. An their members and certificate afterguard on performance sailing boats. approach reflected by a completely holders to Seahorse as a benefit international reach adopt and adapt this important information into their design work. -

March 16,1865

*Wima&mvciA~ Jit (ll I / < I ,s *'*iMt**Sf *««* ihnll ,-gaiatf^ a^bxjt ,DM.U —*“r ■*♦•- >’-*wA *i: aft _ “ ri A ■j"i?”s'"1 »iii*V ■«**■> tit * wrs»jt' i 4»Y>fw*-.»Sir^'> v,wi ".■i.,i:.!:L.^i.Y- ■' _ MahlMed June syear, in advance. "v^PMHiSSnKaacantt —n a- a.„n -,r i snow till at length I made my way into the ;>aTLAI3D Is AIL i KH3BB, * main igloo. Nukerton was not dead! She MISCELLANEOUS. MISCELLANEOUS. FOR BALE & TO LET. BUSINESS CARDS. BUSINESS CARlib. soiil, 1’. WiEMAIK. Editor, bieathed,and was much about the same as j merchandise. when I last saw her. I determined then to j ~=' .re puL'Ilehsa st He. 3XKSSXX.ay For Male. U IS SLl WP D « G2*EXCHANGE what I could for the CITY OF Dana & Co. H remain, doing dylug,— PORTLAND subscriber offers his fans* situated in Yar. i%ew & the 1865. Crop Sugar. Ti. A. FOSTER CO. The lamp was nearly out, cold was h»tcuee, PROSPECTUS FOR THEm u h, containing 45 ac es of good i&cd in- the thennometer outside being 51 degrees be- cluding abou' 6 a ires woodland. A two story Fish and SEWING l 8°I«i(l'8n«nUoag|U, and car, Sait, MAC FINES 150 the and I home, wood isg> huus >&. *»nd b »rn wit c-1 ,84 Rrxee Yellow now 1 AroR-rLABX>,>.iur low freezing point; though had on 0 Sugar, l.nding* fro:* FuK3eiapuiiiifiiiedat*s.ot B U NT IE S ! lar an ore an cf about 40 tree*, good Iruit Tl ere f.om M»l>iaaa. -

USA Wins 33Rd America's Cup Match

Volume XXI No. 2 April/May 2010 USAUSA winswins 33rd33rd America’sAmerica’s CupCup MatchMatch BMW ORACLE Racing Team’s revolutionary wing sail powered trimaran USA Over 500 New and Used Boats Call for 2010 Dockage MARINA & SHIP’S STORE Downtown Bayfield Seasonal & Guest Dockage, Nautical Gifts, Clothing, Boating Supplies, Parts & Service 715-779-5661 apostleislandsmarina.net 2 Visit Northern Breezes Online @ www.sailingbreezes.com - April/May 2010 New New VELOCITEK On site INSTRUMENTS Sail repair IN STOCK AT Quick, quality DISCOUNT service PRICES Do it Seven Seas is now part of Shorewood Marina • Same location on Lake Minnetonka • Same great service, rigging, hardware, cordage, paint Lake Minnetonka’s • Inside boat hoist up to 27 feet—working on boats all winter Premier Sailboat Marina • New products—Blue Storm inflatable & Stohlquist PFD’s, Rob Line high-tech rope Now Reserving Slips for Spring Hours Mon & Wed Open House the 2010 Sailing Season! 9-7 Tues-Thur-Fri Saturday 8-5 April 10th Sat 9-3 Free food Closed Sundays Open House April 10th Are You Ready for Summer? 600 West Lake St., Excelsior, MN 55331 Just ½ mile north of Hwy 7 on Co. Rd. 19 952-474-0600 952-470-0099 [email protected] www.shorewoodyachtclub.com S A I L I N G S C H O O L Safe, fun, learning Learn to sail on Three Metro Lakes; Also Leech Lake, MN; Pewaukee Lake, WI; School of Lake Superior, Apostle Islands, Bayfield, WI; Lake Michigan; Caribbean Islands the Year On-the-water courses weekends, week days, evenings starting May: Gold Standard • Basic Small Boat -

Update: America's

maxon motor Australia Pty Ltd Unit 1, 12 -14 Beaumont Rd. Mount Kuring -Gai NSW 2080 Tel. +61 2 9457 7477 [email protected] www.maxongroup.net.au October 02, 2019 The much -anticipated launch of the first two AC75 foiling monohull yachts from the Defender Emir- ates Team New Zealand and USA Challenger NYYC American Magic respectively did not disappoint the masses of America’s Cup fans waiting eagerly for their first gl impse of an AC75 ‘in the flesh’. Emirates Team New Zealand were the first to officially reveal their boat at an early morning naming cere- mony on September 6. Resplendent in the team’s familiar red, black and grey livery, the Kiwi AC75 was given the Maori nam e ‘Te Aihe’ (Dolphin). Meanwhile, the Americans somewhat broke with protocol by carrying out a series of un -announced test sails and were the first team to foil their AC75 on the water prior to a formal launch ceremony on Friday September 14 when their dark blue boat was given t he name ‘Defiant’. But it was not just the paint jobs that differentiated the first two boats of this 36th America’s Cup cycle – as it quickly became apparent that the New Zealand and American hull designs were also strikingly differ- ent.On first compar ison the two teams’ differing interpretations of the AC75 design rule are especially obvi- ous in the shape of the hull and the appendages. While the New Zealanders have opted for a bow section that is – for want of a better word – ‘pointy’, the Americans h ave gone a totally different route with a bulbous bow that some have described as ‘scow -like’ – although true scow bows are prohibited in the AC75 design rule. -

America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club V. Societe Nautique De Geneve

Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 5 2011 America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club v. Societe Nautique de Geneve Joseph F. Dorfler Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Joseph F. Dorfler, America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club v. Societe Nautique de Geneve, 18 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 267 (2011). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol18/iss1/5 This Casenote is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Dorfler: America's Cup in America's Court: Golden Gate Yacht Club v. Socie Casenotes AMERICA'S CUP IN AMERICA'S COURT: GOLDEN GATE YACHT CLUB V. SOCIETE NAUTIQUE DE GENEVD I. INTRODUCTION: "THE OLDEST CONTINUOUS TROPHY IN SPORTS" 2 One-hundred and thirty-seven ounces of solid silver, standing over two feet tall, this "One Hundred Guinea Cup" created under the authorization of Queen Victoria in 1848 is physically what is at stake at every America's Cup regatta.3 However, it is the dignity, honor, and national pride that attach to the victor of this cherished objet d'art that have been the desire of the yacht racing community since its creation. 4 Unfortunately, this desire often turns to envy and has driven some to abandon concepts of sportsmanship and operate by "greed, commercialism and zealotry."5 When these prin- ciples clash "the outcome of the case [will be] dictated by elemental legal principles."6 1. -

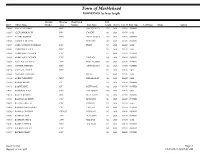

Active Waitlist Main Alphabetical

Town of Marblehead MOORINGS by boat length Mooring Mooring Registration Boat Bill # Owner Name Number Area Number Boat Name Length Res Ty Cove M Boat Type Cell Phone Phone Address 104948 AINLAY STEPHEN BYC TRANQUILITY 026 2020 MAIN POWER 103837 ALEXANDER JOHN BYC URGENT 033 2020 MAIN SAIL 103830 ALPERT ROBERT BYC SWIFT CLOUD 030 2020 MAIN POWER 104543 AMBERIK MELISSA PRELUDE 020 2020 MAIN POWER 102968 AMES- LAWSON DANIELLE EYC FLIRT 034 2020 MAIN SAIL 105636 ANDERSON CARLY BYC 028 2020 MAIN SAIL 104302 ANDREASEN PATRICK EYC 017 2020 MAIN POWER 104803 ANDREASEN PATRICK EYC VINTAGE 036 2020 MAIN POWER 105288 ANNUNZIATA SCOTT ANY REEL PATRIOT 030 2020 MAIN POWER 105103 ARTHUR STEPHEN BYC ANCHORMAN 026 2020 MAIN POWER 104254 ASPINALL JENNIE BYC 033 2020 MAIN SAIL 105828 ASPINALL JENNIFER DAISY 017 2020 MAIN SAIL 103408 AUBIN CHRISTINE MYC BREAKAWAY 040 2020 MAIN SAIL 105030 BABINE BRYCE LIT 015 2020 MAIN POWER 104676 BABINE PETE LIT BETTI ROSE 022 2020 MAIN POWER 104022 BACKMAN ELKE EYC SARABAND 036 2020 MAIN SAIL 104674 BAILEY DAMIEN DYC BLUE STEEL 023 2020 MAIN POWER 104163 BALUNAS ANDREW CYC MOHAWK 021 2020 MAIN POWER 104498 BALUNAS DYLAN CYC PATRICK 013 2020 MAIN power 105165 BARBER JOHN FORBES CYC CANTAB 032 2020 MAIN POWER 105740 BARNES GREGORY COM ST LOW-KEY 023 2020 MAIN POWER 103845 BARRETT JACK ANY SLAP SHOT 017 2020 MAIN POWER 104846 BARRETT STEVE ANY RELAPSE 033 2020 MAIN SAIL 104315 BARRY STEPHEN BYC SEA STAR 023 2020 MAIN POWER 105998 BECKER GENEVA EYC 024 2020 MAIN POWER 105997 BECKER GRADY EYC 024 2020 MAIN POWER User: TerryT -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S.