Men and Vegetarianism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm

[Expositions 6.1 (2012) 29–40] Expositions (online) ISSN: 1747–5376 Unnaturally Cruel: Rolston on Animals, Ethics, and the Factory Farm CHRISTIAN DIEHM University of Wisconsin, Stevens Point In 2010, over nine billion animals were killed in the United States for human consumption. This included nearly 1 million calves, 2.5 million sheep and lambs, 34 million cattle, 110 million hogs, 242 million turkeys, and well over 8.7 billion chickens (USDA 2011a; 2011b). Though hundreds of slaughterhouses actively contributed to these totals, more than half of the cattle just mentioned were killed at just fourteen plants. A slightly greater percentage of hogs was killed at only twelve (USDA 2011a). Chickens were processed in a total of three hundred and ten federally inspected facilities (USDA 2011b), which means that if every facility operated at the same capacity, each would have slaughtered over fifty-three birds per minute (nearly one per second) in every minute of every day, adding up to more than twenty-eight million apiece over the course of twelve months.1 Incredible as these figures may seem, 2010 was an average year for agricultural animals. Indeed, for nearly a decade now the total number of birds and mammals killed annually in the US has come in at or above the nine billion mark, and such enormous totals are possible only by virtue of the existence of an equally enormous network of industrialized agricultural suppliers. These high-volume farming operations – dubbed “factory farms” by the general public, or “Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs)” by state and federal agencies – are defined by the ways in which they restrict animals’ movements and behaviors, locate more and more bodies in less and less space, and increasingly mechanize many aspects of traditional husbandry. -

The Sexual Politics of Meat by Carol J. Adams

THE SEXUAL POLITICS OF MEAT A FEMINISTVEGETARIAN CRITICAL THEORY Praise for The Sexual Politics of Meat and Carol J. Adams “A clearheaded scholar joins the ideas of two movements—vegetari- anism and feminism—and turns them into a single coherent and moral theory. Her argument is rational and persuasive. New ground—whole acres of it—is broken by Adams.” —Colman McCarthy, Washington Post Book World “Th e Sexual Politics of Meat examines the historical, gender, race, and class implications of meat culture, and makes the links between the prac tice of butchering/eating animals and the maintenance of male domi nance. Read this powerful new book and you may well become a vegetarian.” —Ms. “Adams’s work will almost surely become a ‘bible’ for feminist and pro gressive animal rights activists. Depiction of animal exploita- tion as one manifestation of a brutal patriarchal culture has been explored in two [of her] books, Th e Sexual Politics of Meat and Neither Man nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. Adams argues that factory farming is part of a whole culture of oppression and insti- tutionalized violence. Th e treatment of animals as objects is parallel to and associated with patriarchal society’s objectifi cation of women, blacks, and other minorities in order to routinely exploit them. Adams excels in constructing unexpected juxtapositions by using the language of one kind of relationship to illuminate another. Employing poetic rather than rhetorical techniques, Adams makes powerful connec- tions that encourage readers to draw their own conclusions.” —Choice “A dynamic contribution toward creating a feminist/animal rights theory.” —Animals’ Agenda “A cohesive, passionate case linking meat-eating to the oppression of animals and women . -

Journal of Animal & Natural Resource

JOURNAL OF ANIMAL & NATURAL RESOURCE LAW Michigan State University College of Law MAY 2018 VOLUME XIV The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law is published annually by law students at Michigan State University College of Law. JOURNAL OF ANIMAL & The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law received generous support from NATURAL RESOURCE LAW the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law. Without their generous support, the Journal would not have been able to publish and VOL. XIV 2018 host its annual symposium. The Journal also is funded by subscription revenues. Subscription requests and article submissions may be sent to: Professor David Favre, Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law, Michigan State University College of EDITORIAL BOARD Law, 368 Law College Building, East Lansing MI 48824, or by email to msujanrl@ gmail.com. 2017-2018 Current yearly subscription rates are $27.00 in the U.S. and current yearly Internet Editor-in-Chief subscription rates are $27.00. Subscriptions are renewed automatically unless a request AYLOR ATERS for discontinuance is received. T W Back issues may be obtained from: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285 Main Street, Executive Editor & Notes Editor Buffalo, NY 14209. JENNIFER SMITH The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law welcomes the submission of articles, book reviews, and notes & comments. Each manuscript must be double spaced, in Managing Editor & Business Editor 12 point, Times New Roman; footnotes must be single spaced, 10 point, Times New INDSAY EISS Roman. Submissions should be sent to [email protected] using Microsoft Word or L W PDF format. -

I Mmmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I Mmmmmmmmmm 5A Gross Rents

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¼ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2018 or tax year beginning 02/01 , 2018, and ending 01/31 , 20 19 Name of foundation A Employer identification number SALESFORCE.COM FOUNDATION 94-3347800 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 50 FREMONT ST 300 (866) 924-0450 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption applicatmionm ism m m m m m I pending, check here SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105 m m I G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm hem rem anmd am ttamchm m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization: X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminamtedI Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminmatIion end of year (from Part II, col. -

Review of Marti Kheel: “Nature Ethics: an Ecofeminist Perspective” [2008

Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume VI, Issue 1, 2008 Book Review: Nature Ethics: An Ecofeminist Perspective, Kheel, Marti (Rowman Littlefield 2008) Lynda Birke1 “There are plenty more where that came from.” So I was told when, as a trainee biologist, I became upset at the death of a lab rat. So too said the Division of Wildlife to a woman concerned to find orphaned fox kits in Colorado - the example with which Kheel begins this book. It is a widespread assumption that as long as there are enough animals to make up a robust population of the species, then the loss of one or two simply does not matter. And there is another message: that emotional responses, such as my grief for the rat or the unknown woman’s empathy for baby foxes, do not matter. What is important, it would seem, is survival of species or ecosystems. There is undoubtedly a tension between such a stance in writing about environmental ethics, and the concerns of animal liberation. For the latter, individual suffering and death matters a great deal, and there cannot be a justification for killing animals in the name of any greater good. In Nature Ethics, feminist activist and writer Marti Kheel explores ideas about nature in the work of environmentalist thinkers: but, significantly, she seeks to do so through challenging the assumption that individuals are not important. Her task is to find an ethics which pays attention to both nature in general and simultaneously to individual animals and their suffering. Kheel’s odyssey began with concern about how humans treat other animals (whom she calls “other-than-humans”), but she found neither environmental nor animal liberation philosophy to be helpful. -

The Growing Disparity in Protection Between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals Elizabeth Ann Overcash

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 90 | Number 3 Article 7 3-1-2012 Unwarranted Discrepancies in the Advancement of Animal Law:? The Growing Disparity in Protection between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals Elizabeth Ann Overcash Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Elizabeth A. Overcash, Unwarranted Discrepancies in the Advancement of Animal Law:? The Growing Disparity in Protection between Companion Animals and Agricultural Animals, 90 N.C. L. Rev. 837 (2012). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol90/iss3/7 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNWARRANTED DISCREPANCIES IN THE ADVANCEMENT OF ANIMAL LAW: THE GROWING DISPARITY IN PROTECTION BETWEEN COMPANION ANIMALS AND AGRICULTURAL ANIMALS* INTRO D U CT IO N ....................................................................................... 837 I. SU SIE'S LA W .................................................................................. 839 II. PROGRESSION OF LAWS OVER TIME ......................................... 841 A . Colonial L aw ......................................................................... 842 B . The B ergh E ra........................................................................ 846 C. Modern Cases........................................................................ -

Vulnerability, Care, Power, and Virtue: Thinking Other Animals Anew

Vulnerability, Care, Power, and Virtue: Thinking Other Animals Anew by Stephen Thierman A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Philosophy University of Toronto © Copyright by Stephen Thierman 2012 Vulnerability, Care, Power, and Virtue: Thinking Other Animals Anew Stephen Thierman Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Toronto 2012 Abstract This thesis is a work of practical philosophy situated at the intersection of bioethics, environmental ethics, and social and political thought. Broadly, its topic is the moral status of nonhuman animals. One of its pivotal aims is to encourage and foster the “sympathetic imaginative construction of another’s reality”1 and to determine how that construction might feed back on to understandings of ourselves and of our place in this world that we share with so many other creatures. In the three chapters that follow the introduction, I explore a concept (vulnerability), a tradition in moral philosophy (the ethic of care), and a philosopher (Wittgenstein) that are not often foregrounded in discussions of animal ethics. Taken together, these sections establish a picture of other animals (and of the kinship that humans share with them) that can stand as an alternative to the utilitarian and rights theories that have been dominant in this domain of philosophical inquiry. 1 Josephine Donovan, “Attention to Suffering: Sympathy as a Basis for the Ethical Treatment of Animals,” in The Feminist Care Tradition in Animal Ethics, ed. Josephine Donovan and Carol Adams (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 179. ii In my fifth and sixth chapters, I extend this conceptual framework by turning to the work of Michel Foucault. -

Full Article

04_HIROKAWA.DOCX 2/22/2011 10:36 AM PROPERTY AS CAPTURE AND CARE Keith H. Hirokawa* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................ 176 II. SEEING CAPTURE AND CARE IN PROPERTY ...................... 180 A. Legitimate Property Expectations in Transfers of Title: Capture, Relationship, and Responsibility ............... 185 1. Adverse Possession ............................................. 187 2. Termination of Co-Tenancy: Partition................ 189 3. Conveyancing: Caveat Emptor and Informational Duties .................................................................. 192 B. Interests in the Property of Others: Capture, Context, and Community ................................................................ 196 1. Nuisance Law ...................................................... 197 2. Eminent Domain and Public Use ....................... 202 C. Interests in Natural Resources: Capture, Nature, and Collaboration ............................................................ 206 1. The Public Trust ................................................. 209 2. Groundwater: Capture and Correlative Rights .. 212 D. Regulatory Care of Market Captures: Land Use and Environmental Law .................................................. 220 1. The Local Exchange Between Capture and Care: Land Use Control ......................................................... 223 2. The Federal Negotiation: Environmental Law and Pollution Prevention ........................................... 227 III. REMARKS ON SKETCHES OF A PROPERTY -

Il Veganismo Tra Identità, Etica E Stile Di Vita

SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO-BICOCCA Dipartimento di Sociologia e Ricerca Sociale Dottorato di Ricerca in Sociologia Applicata e Metodologia della Ricerca Sociale Ciclo XXX La rivoluzione parte dal piatto? Il veganismo tra identità, etica e stile di vita Mininni Francesca Matricola 706234 Tutore: Andrea Cerroni Coordinatrice: Prof.ssa Carmen Leccardi ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016/2017 PREMESSA ........................................................................................................................... 4 INTRODUZIONE ................................................................................................................. 10 PRIMA PARTE .................................................................................................................... 17 INQUADRAMENTO TEORICO .............................................................................................. 18 1.1 PERCHÉ GLI ANIMALI IN SOCIOLOGIA? .................................................................................... 18 1.1.1 SPECISMO E ANTISPECISMO: ORIGINE E AFFERMAZIONE ................................................................. 27 1.1.2 ROTTURA DEL SENSO COMUNE E INNOVAZIONE CULTURALE: L'ANTISPECISMO .................................... 34 1.1.3 L'ANTISPECISMO: DALLA TEORIA AL MOVIMENTO .......................................................................... 37 1.2 ETICA, ANIMALI NON-UMANI E SOCIOLOGIA. QUALI CONNESSIONI? .............................................. 42 1.3 RIFLESSIVITÀ: TEORIA E PRATICA DI UNA -

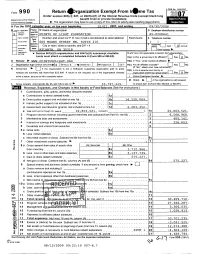

I Return .Rganization Exempt from Ir*Me Tax R

Form 9 9 0 I Return .rganization Exempt From Ir*me Tax r Under section 501 (c); 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung Department 01 the Treasury benefit trust or private foundation) Internal Revenue Service 10- The organization may have to use a copy of this r eturn to satisfy state report ing requirements A For the 2007 calendar year , or tax year beginninq 10/01 , 2007 , and endinq 09/30/2008 Please B Check d epphcable C Name of organization D Employer identification number Add,ess use IRS X change' label or POINTS OF LIGHT FOUNDATION 65-0206641 print or Name change Number and street (or P box if mail is not delivered street address) Room/ E Telephone number type. 0 to suite Imtialretun see 600 MEANS STREET NW SUITE 210 - Specific F Acc-nr.,q Termination l instrur - City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 method Cash X Accrual Amended bons return Other ( specify) ► Application pending • Section 501 ( c )( 3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990 -EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affil ates> Yes F-xl No G Website : ► WWW. POINTSOFLIGHT . ORG H(b) If "Yes," enter number of affiliates ► _ J Organization type (check only one) ► X 501(c) ( 3 ) 4 (Insert no) 4947(a)(1) or 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included? Yes ^No (If "No," attach a list See instructions K Check here ► If the organization is not a 509(a)(3) supporting organization and its gross H(d) Is this a separate return filedroubypan receipts are normally not more than $25,000 A return is not required, but if the organization chooses org anizat ion covered by a rul ing'? Yes X No to file a return , be sure to file a complete return I Group Exemption Number ► M Check ► If the organization is not required L Gross receipts Add lines 6b, 8b, 9b , and lob to line 12 ► 33 , 797 , 449. -

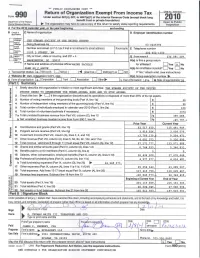

2010-Form-990.Pdf

Form 990 (2010) THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES 53-0225390 Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response to any question in this Part III X 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission: THE HUMANE SOCIETY OF THE UNITED STATES' MISSION IS TO CELEBRATE ANIMALS AND CONFRONT CRUELTY. MORE INFORMATION ON THE HSUS'S PROGRAM SERVICE ACCOMPLISHMENTS IS AVAILABLE AT HUMANESOCIETY.ORG AND SCHEDULE O. 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Yes X No If "Yes," describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services?~~~~~~ Yes X No If "Yes," describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the exempt purpose achievements for each of the organization's three largest program services by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations and section 4947(a)(1) trusts are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 22,977,317. including grants of $ 461,691. ) (Revenue $ 1,462,226. ) RESEARCH AND EDUCATION THE WORK OF RESEARCH AND EDUCATION, WITH THE RELATED ACTIVITIES OF PUBLIC EDUCATION AND OUTREACH, IS A CORE ELEMENT OF THE WORK OF THE HSUS. THIS WORK IS CONDUCTED THROUGH MANY CHANNELS, INCLUDING VIA SECTIONS SUCH AS COMMUNICATIONS, MEDIA AND PUBLIC RELATIONS, SPECIAL EVENTS, PUBLICATIONS, HUMANE SOCIETY YOUTH, THE HUMANE SOCIETY INSTITUTE FOR SCIENCE AND POLICY, FAITH OUTREACH, AND THE HSUS HOLLYWOOD OFFICE. -

It Shouldn't Happen to a Dog? the Trial of the SHAC 7

It Shouldn’t Happen to a Dog? The Trial of the SHAC 7 (2006) The Roots of the Animal Rights Movement © James Ottavio Castagnera 2011 In his novel of seventeenth-century England, Quicksilver, author Neal Stephenson has members of the Royal Society “starving a toad in a jar to see if new toads would grow out of it,”i draining “all the blood out of a large dog and putting it into a smaller dog minutes later,”ii and removing “the rib cage from a living mongrel.”iii Since Stephenson’s representations appear to be historically accurate, little wonder that the “first significant animal rights movement began in nineteenth-century England, where the impetus was opposition to the use of un-anaesthetized animals in scientific research.”iv The only wonder is that it took so long for social mores to rise to the level of repugnance for this practice that the “movement inspired protests, legislative reforms in the United Kingdom, and the birth of numerous animal protection organizations….”v [Painting by Emile-Edouard Mouchy] The rise of such sentiments paralleled the changing views of England’s leading philosophers (including so-called “natural philosophers”) toward animals. While Rene Descartes considered animals to be “organic machines,”vi David Hume wrote in the eighteenth century, “Next to the ridicule of denying an evident truth, is that of taking much pains to defend it; and no truth appears to me more evident, than that beasts are endow'd with thought and reason as well as men. The arguments are in this case so obvious, that they never escape the most stupid and ignorant.”vii Jeremy Bentham, the early-nineteenth-century father of Utilitarianism, added, “Other animals…, on account of their interests having been neglected by the insensibility of the ancient jurists, stand degraded into the class of things...