Tasevska EF 2020 Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of the Rose Tattoo

RSA JOU R N A L 25/2014 GIULIANA MUS C IO A Transcultural Perspective on the Casting of The Rose Tattoo A transcultural perspective on the film The Rose Tattoo (Daniel Mann, 1955), written by Tennessee Williams, is motivated by its setting in an Italian-American community (specifically Sicilian) in Louisiana, and by its cast, which includes relevant Italian participation. A re-examination of its production and textuality illuminates not only Williams’ work but also the cultural interactions between Italy and the U.S. On the background, the popularity and critical appreciation of neorealist cinema.1 The production of the film The Rose Tattoo has a complicated history, which is worth recalling, in order to capture its peculiar transcultural implications in Williams’ own work, moving from some biographical elements. In the late 1940s Tennessee Williams was often traveling in Italy, and visited Sicily, invited by Luchino Visconti (who had directed The Glass Managerie in Rome, in 1946) for the shooting of La terra trema (1948), where he went with his partner Frank Merlo, an occasional actor of Sicilian origins (Williams, Notebooks 472). Thus his Italian experiences involved both his professional life, putting him in touch with the lively world of Italian postwar theater and film, and his affections, with new encounters and new friends. In the early 1950s Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a play for Anna Magnani, protagonist of the neorealist masterpiece Rome Open City (Roberto Rossellini, 1945). However, the Italian actress was not yet comfortable with acting in English and therefore the American stage version (1951) starred Maureen Stapleton instead and Method actor Eli Wallach. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

Vivre Sa Vie Nathaniel Dorsky Kinorama Antichrist O Plano Frontal

TODA A POESIA QUE VINICIUS VIU NO CINEMA, POR CARLOS A. CALIL O BOLETIM DO ANO 35 N162 CINE CLUBE DE VISEU JUNHO 2019 2 EUROS QUADRIMESTRAL O INCONTORNÁVEL GODARD NA RETINA DE Vivre sa vie MARIA JOÃO MADEIRA ANA BARROSO NOS PASSOS DO CINEMA LUMINOSO DE Nathaniel Dorsky O NOVO PROJECTO DE EDGAR PÊRA É O MOTE PARA Kinorama UMA CONVERSA COM EDUARDO EGO DE LARS VON TRIER COMEMORA UMA DÉCADA E FILIPE VARELA Antichrist ESCREVE-NOS SOBRE ELE EM ‘NÓS POR CÁ’, FAUSTO CRUCHINHO REFLECTE SOBRE O plano frontal DISCURSO VISUAL E DISTORÇÃO DA REALIDADE em televisão POR MANUEL PEREIRA A retórica do poder JARMUSCH INSPIRA ANDRÉ RUIVO NO Dead Man SEU ‘OBSERVATÓRIO’ 162 VIVRE SA VIE NA RETINA DE MARIA JOÃO MADEIRA GRIFFITH DIZIA QUE ERA TUDO O QUE ERA PRECISO, GODARD CITA-O POR ESCRITO: A FILM IS A GIRL AND A GUN. Na capa, Charlotte Gainsbourg, num fotograma de Antichrist (Lars von Trier, 2009). Por causa de uma crónica, uma ilustração, um ensaio, mais cedo ou mais tarde o Argumento vai fazer falta. Assinaturas €10 5 EDIÇÕES HTTP://WWW.CINECLUBEVISEU.PT/ARGUMENTO-ASSINATURAS Colaboram neste número: MARIA JOÃO EDGAR ANA FILIPE FAUSTO MANUEL ANDRÉ MADEIRA PÊRA BARROSO VA R E L A CRUCHINHO PEREIRA RUIVO PROGRAMADORA DE ESTÁ A TERMINAR ANA BARROSO É ESTUDOU CINEMA, PROFESSOR AUXILIAR FORMADO EM ESTUDOS LICENCIADO EM DESIGN CINEMA, SOBRETUDO. KINORAMA — CINE- INVESTIGADORA NO FILOSOFIA E MATEMÁ- DA FACULDADE DE ARTÍSTICOS NA VA- DE COMUNICAÇÃO PELA MA FORA DE ÓRBI- CENTRO DE ESTUDOS TICA. REALIZOU DUAS LETRAS DA UNIVER- RIANTE DE ESTUDOS FBAUL E MESTRE EM TA, A SEQUELA DO ANGLÍSTICOS DA U.L. -

La Géo-Politique De L'image Dans Les Histoire(S) Du Cinéma De Jean-Luc

La Géo-politique de l’image dans les Histoire(s) du cinéma de Jean-Luc Godard1 Junji Hori Les Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988–98) de Jean-Luc Godard s’offre comme un collage kaléidoscopique d’innombrables fragments de films et d’actualités. Nous pouvons cependant tout de suite constater que la plupart des fragments appartiennent au cinéma occidental d’avant la Nouvelle Vague. L’inventaire de films cités contient aussi peu d’œuvres contemporaines que venant d’Asie et du tiers-monde. Mais cet eurocentrisme manifeste des Histoire(s) n’a curieusement pas fait l’objet d’attentions spéciales, et ce malgré la prospérité intellectuelle des Études culturelles et du post- colonialisme dans le monde anglo-américain des années 90. Il arrive certes que certains chercheurs occidentaux mentionnent brièvement le manque de référence au cinéma japonais dans l’encyclopédie de Godard, mais il n’y a que très peu de recherches qui sont véritablement consacrées à ce sujet. Nous trouvons toutefois une critique acharnée contre l’eurocentrisme des Histoire(s) dans un article intitulé Ç Pacchoro » de Inuhiko Yomota. Celui-ci signale que les films cités par Godard fournissent un panorama très imparfait par rapport à la situation actuelle du cinéma mondial et que ses choix s’appuient sur une nostalgie toute personnelle et un eurocentrisme conscient. Les Histoire(s) font abstraction du développement cinémato- graphique d’aujourd’hui de l’Asie de l’Est, de l’Inde et de l’Islam et ainsi manquent- elles de révérence envers les autres civilisations. Il reproche finalement à l’ironiste Godard sa vie casanière en l’opposant à l’attitude accueillante de l’humoriste Nam Jun Paik2. -

Introduction 1 Mimesis and Film Languages

Notes Introduction 1. The English translation is that provided in the subtitles to the UK Region 2 DVD release of the film. 2. The rewarding of Christoph Waltz for his polyglot performance as Hans Landa at the 2010 Academy Awards recalls other Oscar- winning multilin- gual performances such as those by Robert de Niro in The Godfather Part II (Coppola, 1974) and Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice (Pakula, 1982). 3. T h is u nder st a nd i ng of f i l m go es bac k to t he era of si lent f i l m, to D.W. Gr i f f it h’s famous affirmation of film as the universal language. For a useful account of the semiotic understanding of film as language, see Monaco (2000: 152–227). 4. I speak here of film and not of television for the sake of convenience only. This is not to undervalue the relevance of these questions to television, and indeed vice versa. The large volume of studies in existence on the audiovisual translation of television texts attests to the applicability of these issues to television too. From a mimetic standpoint, television addresses many of the same issues of language representation. Although the bulk of the exempli- fication in this study will be drawn from the cinema, reference will also be made where applicable to television usage. 1 Mimesis and Film Languages 1. There are, of course, examples of ‘intralingual’ translation where films are post-synchronised with more easily comprehensible accents (e.g. Mad Max for the American market). -

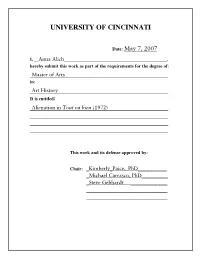

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

'To Realise the Ideal': Miscellaneous Remarks on Godard's Conceptual Processes Apropos of Sauve Qui Peut (La Vie)

‘To Realise the Ideal’: Miscellaneous Remarks on Godard’s Conceptual Processes Apropos of Sauve qui peut (la vie) •Richard Morris Made in 1979, Jean-Luc Godard’s Sauve qui peut photocopied images of the film’s three principal (la vie) occupies a uniquely pivotal position in the actors, Jacques Dutronc, Isabelle Huppert and director’s career, representing as it does the Miou-miou (replaced in the completed film by closing, culminatory opus of one decade and the Natalie Baye). These images rise up through the inaugural work of another. It is not, however, my machine as the paper feeds through it whilst the intention to address the specified film in a direct print head moves back and forth typing the way. I shall instead be talking around it, so to film’s title over the images. Meanwhile, Godard speak, with a view to exploring something of comments offscreen upon these two axes of how Godard actually conceives his works. It is my movement: one vertical, one horizontal, and on hope that in adopting this approach my the order of precedence between words and observations may acquire some more general images. He goes on to talk about the three relevance to Godard’s work throughout the characters whom he relates to differing abstract 1980s and beyond. vectors of movement, a theme I shall return to In embarking upon his first mainstream presently. There is little of any narrative feature since Tout va bien (1972) Godard found significance in this video-scenario beyond talk of himself faced with the problem of how to a desire to leave the big city, a desire originating incorporate something of the technical and with Denise (Miou-miou) who acts on it and conceptual flexibility and freedom which he had aspired to by Jacques (Dutronc) who lags attained as the co-director with Anne-Marie behind.1 Miéville of Sonimage, a kind of private audio- Beyond this, Godard muses on a variety of visual research institute for the production of subjects relating to the production of the film – innovative film, video and TV. -

Of Christophe Honoré: New Wave Legacies and New Directions in French Auteur Cinema

SEC 7 (2) pp. 135–148 © Intellect Ltd 2010 Studies in European Cinema Volume 7 Number 2 © Intellect Ltd 2010. Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/seci.7.2.135_1 ISABELLE VANDERSCHELDEN Manchester Metropolitan University The ‘beautiful people’ of Christophe Honoré: New Wave legacies and new directions in French auteur cinema ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Drawing on current debates on the legacy of the New Wave on its 50th anniversary French cinema and the impact that it still retains on artistic creation and auteur cinema in France auteur cinema today, this article discusses three recent films of the independent director Christophe French New Wave Honoré: Dans Paris (2006), Les Chansons d’amour/Love Songs (2007) and La legacies Belle personne (2008). These films are identified as a ‘Parisian trilogy’ that overtly Christophe Honoré makes reference and pays tribute to New Wave films’ motifs and iconography, while musical offering a modern take on the representation of today’s youth in its modernity. Study- adaptation ing Honoré’s auteurist approach to film-making reveals that the legacy of the French Paris New Wave can elicit and inspire the personal style and themes of the auteur-director, and at the same time, it highlights the anchoring of his films in the Paris of today. Far from paying a mere tribute to the films that he loves, Honoré draws life out his cinephilic heritage and thus redefines the notion of French (European?) auteur cinema for the twenty-first century. 135 December 7, 2010 12:33 Intellect/SEC Page-135 SEC-7-2-Finals Isabelle Vanderschelden 1Alltranslationsfrom Christophe Honoré is an independent film-maker who emerged after 2000 and French sources are mine unless otherwise who has overtly acknowledged the heritage of the New Wave as formative in indicated. -

Roberto Rossellinips Rome Open City

P1: JPJ/FFX P2: FCH/FFX QC: FCH/FFX T1: FCH CB673-FM CB673-Gottlieb-v1 February 10, 2004 18:6 Roberto Rossellini’s Rome Open City Edited by SIDNEY GOTTLIEB Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, Connecticut v P1: JPJ/FFX P2: FCH/FFX QC: FCH/FFX T1: FCH CB673-FM CB673-Gottlieb-v1 February 10, 2004 18:6 PUBLISHED BY THE PRESS SYNDICATE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcon´ 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org C Cambridge University Press 2004 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2004 Printed in the United States of America Typefaces Stone Serif 9.5/13.5 pt. and Gill Sans System LATEX2ε [TB] A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, open city / edited by Sidney Gottlieb. p. cm. – (Cambridge film handbooks) Filmography: Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-521-83664-6 (hard) – ISBN 0-521-54519-6 (pbk.) 1. Roma, citta´ aperta (Motion picture) I. Gottlieb, Sidney. II. Cambridge film handbooks series. PN1997.R657R63 -

Classic French Film Festival 2013

FIFTH ANNUAL CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY Co-presented by Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series Webster University’s Winifred Moore Auditorium, 470 E. Lockwood Avenue June 13-16, 20-23, and 27-30, 2013 www.cinemastlouis.org Less a glass, more a display cabinet. Always Enjoy Responsibly. ©2013 Anheuser-Busch InBev S.A., Stella Artois® Beer, Imported by Import Brands Alliance, St. Louis, MO Brand: Stella Artois Chalice 2.0 Closing Date: 5/15/13 Trim: 7.75" x 10.25" Item #:PSA201310421 QC: CS Bleed: none Job/Order #: 251048 Publication: 2013 Cinema St. Louis Live: 7.25" x 9.75" FIFTH ANNUAL CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL PRESENTED BY Co-presented by Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series The Earrings of Madame de... When: June 13-16, 20-23, and 27-30 Where: Winifred Moore Auditorium, Webster University’s Webster Hall, 470 E. Lockwood Ave. How much: $12 general admission; $10 for students, Cinema St. Louis members, and Alliance Française members; free for Webster U. students with valid and current photo ID; advance tickets for all shows are available through Brown Paper Tickets at www.brownpapertickets.com (search for Classic French) More info: www.cinemastlouis.org, 314-289-4150 The Fifth Annual Classic French Film Festival celebrates St. Four programs feature newly struck 35mm prints: the restora- Louis’ Gallic heritage and France’s cinematic legacy. The fea- tions of “A Man and a Woman” and “Max and the Junkmen,” tured films span the decades from the 1920s through the Jacques Rivette’s “Le Pont du Nord” (available in the U.S. -

Spring 2019 Film Calendar

National Gallery of Art Film Spring 19 I Am Cuba p27 Special Events 11 A Cuba Compendium 25 Janie Geiser 29 Walt Whitman Bicentennial 31 The Arboretum Cycle of Nathaniel Dorsky 33 Roberto Rossellini: The War Trilogy 37 Reinventing Realism: New Cinema from Romania 41 Spring 2019 offers digital restorations of classic titles, special events including a live performance by Alloy Orchestra, and several series of archival and contem- porary films from around the world. In conjunction with the exhibition The Life of Animals in Japanese Art, the Gallery presents Japanese documentaries on animals, including several screenings of the city symphony Tokyo Waka. Film series include A Cuba Compendium, surveying how Cuba has been and continues to be portrayed and examined through film, including an in-person discussion with Cuban directors Rodrigo and Sebastián Barriuso; a celebra- tion of Walt Whitman on the occasion of his bicen- tennial; recent restorations of Roberto Rossellini’s classic War Trilogy; and New Cinema from Romania, a series showcasing seven feature length films made since 2017. Other events include an artist’s talk by Los Angeles-based artist Janie Geiser, followed by a program of her recent short films; a presentation of Nathaniel Dorsky’s 16mm silent The Arboretum Cycle; the Washington premieres of Gray House and The Image Book; a program of films on and about motherhood to celebrate Mother’s Day; the recently re-released Mystery of Picasso; and more. 2Tokyo Waka p17 3 April 6 Sat 2:00 La Religieuse p11 7 Sun 4:00 Rosenwald p12 13 Sat 12:30 A Cuba Compendium: Tania Libre p25 2:30 A Cuba Compendium: Coco Fusco: Recent Videos p26 14 Sun 4:00 Gray House p12 20 Sat 2:00 A Cuba Compendium: Cuba: Battle of the 10,000,000 p26 4:00 A Cuba Compendium: I Am Cuba p27 21 Sun 2:00 The Mystery of Picasso p13 4:30 The Mystery of Picasso p13 27 Sat 2:30 A Cuba Compendium: The Translator p27 Films are shown in the East Building Auditorium, in original formats whenever possible.