THE ROCK and ROLL DIARY of a JAZZ FAN by John Clare ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 May June Newsletter

MAY / JUNE NEWSLETTER CLUB COMMITTEE 2020 CONTENT President Karl Herman 2304946 President Report - 1 Secretary Clare Atkinson 2159441 Photos - 2 Treasurer Nicola Fleming 2304604 Club Notices - 3 Tuitions Cheryl Cross 0275120144 Jokes - 3-4 Pub Relations Wendy Butler 0273797227 Fundraising - 4 Hall Mgr James Phillipson 021929916 Demos - 5 Editor/Cleaner Jeanette Hope - Johnstone Birthdays - 5 0276233253 New Members - 5 Demo Co-Ord Izaak Sanders 0278943522 Member Profile - 6 Committee: Pauline Rodan, Brent Shirley & Evelyn Sooalo Rock n Roll Personalities History - 7-14 Sale and wanted - 15 THE PRESIDENTS BOOGIE WOOGIE Hi guys, it seems forever that I have seen you all in one way or another, 70 days to be exact!! Bit scary and I would say a number of you may have to go through beginner lessons again and also wear name tags lol. On the 9th of May the national association had their AGM with a number of clubs from throughout New Zealand that were involved. First time ever we had to run the meeting through zoom so talking to 40 odd people from around the country was quite weird but it worked. A number of remits were discussed and voted on with a collection of changes mostly good but a few I didn’t agree with but you all can see it all on the association website if you are interested in looking . Also senior and junior nationals were voted on where they should be hosted and that is also advertised on their website. Juniors next year will be in Porirua and Seniors will be in Wanganui. -

Faqs About Cobra Premium Assistance Under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021

FAQS ABOUT COBRA PREMIUM ASSISTANCE UNDER THE AMERICAN RESCUE PLAN ACT OF 2021 April 07, 2021 Set out below are Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) regarding implementation of certain provisions of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP), as it app lies to the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985, commonly called COBRA. These FAQs have been prepared by the Department of Labor (DOL). Like previously issued FAQs (available at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ebsa/about-ebsa/our-activities/resource-center/faqs), these FAQs answer questions from stakeholders to help individuals un derstand the law and benefit from it, as intended. The Department of the Treasury and the I nternal Revenue Service (IRS) have reviewed these FAQs, and, concur in the application of the laws under their jurisdiction as set forth in these FAQs. COBRA Continuation Coverage COBRA continuation coverage provides certain group health plan continuation coverage rights for participants and beneficiaries covered by a group health plan. In general, under COBRA, an individual who was covered by a group health plan on the day before the occurrence of a qualifying event (such as a termination of employment or a reduction in hours that causes loss of coverage under the plan) may be able to elect COBRA continuation coverage upon that qualifying event.1 Individuals with such a right are referred to as qualified beneficiaries. Under COBRA, group health plans must provide covered employees and their families with cer tain notices explaining their COBRA rights. ARP COBRA Premium Assistance Section 9501 of the ARP provides for COBRA premium assistance to help Assistance Eligible Individuals (as defined below in Q3) continue their health benefits. -

Disability Benefits

Disability Benefits SSA.gov What’s inside Disability benefits 1 Who can get Social Security disability benefits? 1 How do I apply for disability benefits? 4 When should I apply and what information do I need? 4 Who decides if I am disabled? 5 How is the decision made? 6 What happens when my claim is approved? 9 Can my family get benefits? 10 How do other payments affect my benefits? 10 What do I need to tell Social Security? 11 When do I get Medicare? 12 What do I need to know about working? 12 The Ticket to Work program 13 Achieving a Better Life Experience (ABLE) Account 13 Contacting Social Security 14 Disability benefits Disability is something most people don’t like to think about. But the chances that you’ll become disabled are probably greater than you realize. Studies show that a 20-year-old worker has a 1-in-4 chance of becoming disabled before reaching full retirement age. This booklet provides basic information on Social Security disability benefits and isn’t meant to answer all questions. For specific information about your situation, you should speak with a Social Security representative. We pay disability benefits through two programs: the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. This booklet is about the Social Security disability program. For information about the SSI disability program for adults, see Supplemental Security Income (SSI) (Publication No. 05-11000). For information about disability programs for children, refer to Benefits For Children With Disabilities (Publication No. 05-10026). -

Inivjo LU ME

1111~ ~~ ~~1 ~~~~if~l~l~l~lllllll ~iniVJO L U ME Sls- lV1ount . _. aure_ ' , ... i - ~~ .~ · .. .,~ - , ARCHIVES) LH I' 1 .M68 2002 c.2 ARCHIVES LHl .M68 2002c.2 Mountain Laurels IN GRATITUDE DR. B. J. ROBINSON The editors of Mountain Laurels wish to take this Opportunity to thank Dr. Robinson For her years of dedicated Service to the betterment Of our cultural Life. Her Joie de vivre, Unerring eye for art, Her hard and effective work, Humanity, love, and contagious laugh Are deeply missed. We dedicate this volume to her. Vol. 8 2002 Editors ........ ... .. ........... ..... .. .. ........ ...... .... ...... Jennifer Koch Judson Wright Managing Editor. ... ... ...... ... ... ... ......... ...... ......... Sarah Ballew Editorial Board ... .... ....... ... ........ .... ......... .. .. .... .. ... Sarah Ballew Brittany Tennant Carol Chester Gordon E. McNeer Brian Jay Corrigan Layout. ....... .. ... ............ .... ....... ... ............ Brian Jay Corrigan Faculty Sponsors and Advisors .... .. ................ Gordon E. McNeer Brian Jay Corrigan Founders... ....... ........ ...... ... ..... ... ................. .. Dr. Sally Allen Dr. Brian Jay Corrigan Front Cover Photo: Rekindled Memories by Debbie Martin Back Cover Photo: Troubled Bridge Over Water by Matthew Koch 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS California by Rachel Warner "Poetry First Place" . 3 Untitled by Rachel Warner "Poetry Second Place" . 4 Smoothed Over by Brandon Barton "Poetry Third Place" . 5 And Yet ... by Amanda L. Wood . 6 Sleepless by Crystal Corn. 7 Untitled by Brittany Tennant . 8 The Stage by Samantha Lovely . 9 James Corbin by Marcus Hawkins . 10 Autumn-tinted by Brittany Tennant. 11 Untitled by Brittany Tennant . 12 5 a.m. Girl by Brittany Tennant. 13 A Love Letter by Anonymous. 14 Why I Can 't Write Poetry by Lori Schink . 15 I Take a Thousand Grains of Sand by Shannon Wright . -

Turn Back Time: the Family

TURN BACK TIME: THE FAMILY In October 2011, my lovely wife, Naomi, responded to an advert from TV production company Wall to Wall. Their assistant producer, Caroline Miller, was looking for families willing to take part in a living history programme. They wanted families who were willing to live through five decades of British history. At the same time, they wanted to retrace the history of those families to understand what their predecessors would have been doing during each decade. Well, as you may have already guessed, Wall to Wall selected the Goldings as one of the five families to appear in the programme. Shown on BBC1 at 9pm from Tuesday 26th June 2012, we were honoured and privileged to film three of the five episodes. As the middle class family in the Edwardian, inter war and 1940s periods, we quite literally had the most amazing experience of our lives. This page of my blog is to share our experiences in more detail – from selection, to the return to normal life! I have done this in parts, starting with ‘the selection process’ and ending with the experience of another family. Much of what you will read was not shown on TV, and may answer some of your questions (those of you who watched it!!). I hope you enjoy reading our story. Of course, your comments are very welcome. PART 1 – THE SELECTION PROCESS I will never forget the moment when I got home from work to be told by Naomi that she had just applied for us to be part of a TV programme. -

Employer-Sponsored Insurance for You and Your Family

Your family deserves to be healthy Employer-sponsored Whether you are able to get your family health coverage through an employer-sponsored plan or by enrolling in a plan on the Health Insurance for You Insurance Marketplace, health insurance is an important part of making sure your family gets the medical care they need. Get them and Your Family insurance today! Employer-sponsored health insurance For American Indians and Alaska Natives Is paid for by a business on behalf of its employees May be offered only to the employee or to the employee and his or her family (spouse and children) Signing your family up through your employer How much will I pay for insurance? Options for when your employer doesn’t cover family Your employer may pay all of the cost or require you to share the cost Understanding what you will pay If your employer offers coverage for your family, you may have to pay a higher percentage of the cost than what you pay for your own insurance Your employer can provide information about how much you will pay for yourself and your family Have questions about your employer’s plan or signing your family up for insurance? Talk to your employer’s human resources department, Visit your Indian health program, Go online to healthcare.gov/tribal, or Call 1-800-318-2596 For more information: Visit go.cms.gov/AIAN @CMSGov #CMSNativeHealth CMS ICN No. 909342-N • August 2016 How can I get health insurance for I have insurance through my myself and my family? employer. -

Contentious Comedy

1 Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era Thesis by Lisa E. Williamson Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Glasgow Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies 2008 (Submitted May 2008) © Lisa E. Williamson 2008 2 Abstract Contentious Comedy: Negotiating Issues of Form, Content, and Representation in American Sitcoms of the Post-Network Era This thesis explores the way in which the institutional changes that have occurred within the post-network era of American television have impacted on the situation comedy in terms of form, content, and representation. This thesis argues that as one of television’s most durable genres, the sitcom must be understood as a dynamic form that develops over time in response to changing social, cultural, and institutional circumstances. By providing detailed case studies of the sitcom output of competing broadcast, pay-cable, and niche networks, this research provides an examination of the form that takes into account both the historical context in which it is situated as well as the processes and practices that are unique to television. In addition to drawing on existing academic theory, the primary sources utilised within this thesis include journalistic articles, interviews, and critical reviews, as well as supplementary materials such as DVD commentaries and programme websites. This is presented in conjunction with a comprehensive analysis of the textual features of a number of individual programmes. By providing an examination of the various production and scheduling strategies that have been implemented within the post-network era, this research considers how differentiation has become key within the multichannel marketplace. -

2021 Registration Form

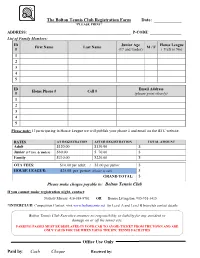

The Bolton Tennis Club Registration Form Date: ____________ *PLEASE PRINT* ADDRESS: ____________________________________________________ P-CODE: ________________ List of Family Members: ID Junior Age House League First Name Last Name M / F # (17 and Under) ( YES or No) 1 2 3 4 5 ID Email Address Home Phone # Cell # # (please print clearly) 1 2 3 4 5 Please note: If participating in House League we will publish your phone # and email on the BTC website. RATES AT REGISTRATION AFTER REGISTRATION TOTAL AMOUNT Adult $120.00 $130.00 $ Junior (17 yrs. & under) $60.00 $ 70.00 $ Family $210.00 $220.00 $ OTA FEES: $10.00 per adult / $3.00 per junior $ HOUSE LEAGUE: $25.00 per person (player or sub) $ GRAND TOTAL: $ Please make cheque payable to: Bolton Tennis Club If you cannot make registration night, contact: Nathaly Murray: 416-888-8781 OR Bonnie Livingston: 905-951-3415 *INTERCLUB Competition Contact: visit www.boltontennis.net for Level A and Level B Interclub contact details Bolton Tennis Club Executive assumes no responsibility or liability for any accident or damage on or off the tennis site. PARKING PASSES MUST BE DISPLAYED IN YOUR CAR TO AVOID TICKET FROM THE TOWN AND ARE ONLY VALID FOR USE WHEN USING THE BTC TENNIS FACILITIES Office Use Only Paid by: Cash Cheque Received by: _____________________________ Informed Consent IN CONSIDERATION OF the Club’s acceptance of my application and, if applicable, my family’s application to be a member --- ON BEHALF OF MYSELF AND ANY OTHER REGISTERED FAMILY MEMBERS AGREE to abide by the following regulations and guidelines of membership in the Club. -

Bring Me Sunshine’ Living Well with Dementia in North Yorkshire

Living Well With Dementia in North Yorkshire ‘Bring Me Sunshine’ Living Well With Dementia in North Yorkshire Signatories to the Living Well Contents with Dementia Strategy: Foreword . 4 Who are ‘we’? . 4 Purpose and scope of the North Yorkshire vision for dementia support . .5 What’s the Picture? . 6 Young Onset Dementia . 6 People with Learning disabilities . 7 Living with dementia and other health conditions . .8 Prevention . 8 Financial Impact - the national picture . 9 What else do we know? . 10 National Strategies . 10 Local Strategies . 12 Primary Care . 13 Secondary (hospital) Care . 14 York Teaching Hospitals - Craven District Council - Representing Mental Health Trusts representing acute hospital providers representing District Council members Overview of activity by area . 16 Mental Health Services . 18 How services are currently set up . 18 Care and Support . 20 Residential and Nursing Quality . 20 Achievements . 21 Accommodation . 23 Pathway . 24 End of Life Care and Support . 25 What matters most to people living with dementia - Consultation and engagement across North Yorkshire . 25 Key themes . 25 Delivering the strategy - action plan . 32 Moving Ahead . 34 Age UK - representing Selby District Council - the voluntary sector representing District Council officers 2 Published: 2017 3 ‘Bring Me Sunshine’ Living Well With Dementia in North Yorkshire Foreword Purpose and scope of the North Welcome to the North Yorkshire Dementia Strategy - ‘Bring Me Sunshine’ . Yorkshire vision for dementia support This strategy brings together organisations awareness of dementia will make a huge This strategy brings together the experiences well known information about people living from across Health and Social Care and the difference to the lives of many people across of those of us living with dementia and our with young onset dementia and people living Voluntary Sector to speak with one voice on North Yorkshire . -

2017 Program

Honoring the Class of 2017 UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Spring Commencement April 29, 2017 | Michigan Stadium Honoring the Class of 2017 SPRING COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 29, 2017 10:00 a.m. This program includes a list of the candidates for degrees to be granted upon completion of formal requirements. Candidates for graduate degrees are recommended jointly by the Executive Board of the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies and the faculty of the school or college awarding the degree. Following the School of Graduate Studies, schools are listed in order of their founding. Candidates within those schools are listed by degree then by specialization, if applicable. Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies .....................................................................................................26 College of Literature, Science, and the Arts ..............................................................................................................36 Medical School .........................................................................................................................................................55 Law School ..............................................................................................................................................................57 School of Dentistry ..................................................................................................................................................59 College of Pharmacy ................................................................................................................................................60 -

* • Most Played Juke Box Folk F Radio Station; Grant Taking (Country & Western) Records 3W 5 / Jocks, Jukes and Disks Based on Reports Received May 30, 31 and June 1

DAILY) 46 ORCHESTRAS- MUSIC Crosby Set to Buy Monterey * • Most Played Juke Box Folk f Radio Station; Grant Taking (Country & Western) Records 3w 5 / Jocks, Jukes and Disks Based on reports received May 30, 31 and June 1 By MIKE CONNOLLY Entertainers to Texas GIs .By HERM SCHOENFELD. Records listed are Country and Western records most played in juke boxes according to The , DOWN THE HATCH: Four masked members of Alcoholics Anony- ^~ t^*S , BY WALTER AMES tS~" 3"~ >S~f Andrews Siste s- Gordon Jenkins chances, Fontane Sisters joining Billboard's special weefcly Mrvay among a selected group of juke bc> operators whose locations require Country and Western records. £J.us are slated to make sobriety pitches on KLAC- TV's "Freedom Orch: "I'm in Love Again"- "It Como for a bouncy side. Mitchell It looks as If Bing Crosby is about to add another radio Never Entered My Mind" (Decca). Ayres orch backs up. POSITION jjkrum some Sunday soon. Sunday, by coincidence, is Hangover station to his two- station chain. Over the week end he filed an A click double- decker of standards Nat "King" Cole: "My Brother"- Weeks | Last I this Ay for some of our best friends . Jack Schwarz Productions to date| WeekiWeek application with the Federal Communications Commission for by the same team which hit last "Early American" (Capitol). A I •« been refinanced to the tune of 250 G's . Local seven- cent year with "I Wanna Be Loved." coupling of dubious tunes for the 6 3 1. 1 WANT TO BE WITH YOU permission to purchase KMBY at Monterey, Cal. -

The Perth Sound in the 1960S—

(This is a combined version of two articles: ‘‘Do You Want To Know A Secret?’: Popular Music in Perth in the Early 1960s’ online in Illumina: An Academic Journal for Performance, Visual Arts, Communication & Interactive Multimedia, 2007, available at: http://illumina.scca.ecu.edu.au/data/tmp/stratton%20j%20%20illumina%20p roof%20final.pdf and ‘Brian Poole and the Tremeloes or the Yardbirds: Comparing Popular Music in Perth and Adelaide in the Early 1960s’ in Perfect Beat: The Pacific Journal for Research into Contemporary Music and Popular Culture, vol 9, no 1, 2008, pp. 60-77). Brian Poole and the Tremeloes or the Yardbirds: Comparing Popular Music in Perth and Adelaide in the Early 1960s In this article I want to think about the differences in the popular music preferred in Perth and Adelaide in the early 1960s—that is, the years before and after the Beatles’ tour of Australia and New Zealand, in June 1964. The Beatles played in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Adelaide but not in Perth. In spite of this, the Beatles’ songs were just as popular in Perth as in the other major cities. Through late 1963 and 1964 ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand,’ ‘I Saw Her Standing There,’ ‘Roll Over Beethoven’ and the ‘All My Loving’ EP all reached the number one position in the Perth chart as they did nationally.1 In this article, though, I am not so much interested in the Beatles per se but rather in their indexical signalling of a transformation in popular music tastes. As Lawrence Zion writes in an important and surprisingly neglected article on ‘The impact of the Beatles on pop music in Australia: 1963-1966:’ ‘For young Australians in the early 1960s America was the icon of pop music and fashion.’2 One of the reasons Zion gives for this is the series of Big Shows put on by American entrepreneur Lee Gordon through the second half of the 1950s.