Qohelet's Philosophies of Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spiritual Aftereffects of Incongruous Near-Death Experiences: a Heuristic Approach

SPIRITUAL AFTEREFFECTS OF INCONGRUOUS NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES: A HEURISTIC APPROACH A dissertation presented to the Faculty of Saybrook University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Sciences by Robert Waxman San Francisco, California November 2012 UMI Number: 3552161 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3552161 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 UMI Number: All rights reserved © 2012 by Robert Waxman Approval of the Dissertation SPIRITUAL AFTEREFFECTS OF INCONGRUOUS NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES: A HEURISTIC APPROACH This dissertation by Robert Waxman has been approved by the committee members below, who recommend it be accepted by the faculty of Saybrook University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Sciences Dissertation Committee: ______________________________ ________________________ Robert McAndrews, Ph.D., Chair Date ______________________________ ________________________ Stanley Krippner, Ph.D. Date ______________________________ ________________________ Willson Williams, Ph.D. Date ii Abstract SPIRITUAL AFTEREFFECTS OF INCONGRUOUS NEAR-DEATH EXPERIENCES: A HEURISTIC APPROACH Robert Waxman Saybrook University Many individuals have experienced a transformation of their spirituality after a near-death experience (NDE). -

Ibtihaj Muhammad's

Featuring 484 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA Books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVI, NO. 15 | 1 AUGUST 2018 REVIEWS U.S. Olympic medalist Ibtihaj Muhammad’s memoir, Proud, released simultaneously in two versions—one for young readers, another for adults—is thoughtful and candid. It’s also a refreshingly diverse Cinderella story at a time when anti-black and anti-Muslim sentiments are high. p. 102 from the editor’s desk: Chairman Excellent August Books HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY CLAIBORNE SMITH MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy Michael Thad Carter courtesy Photo Editor-in-Chief Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World by Anana CLAIBORNE SMITH Giridharadas (Aug. 28): “Give a hungry man a fish, and you get to pat [email protected] Vice President of Marketing yourself on the back—and take a tax deduction. It’s a matter of some SARAH KALINA [email protected] irony, John Steinbeck once observed of the robber barons of the Gilded Managing/Nonfiction Editor ERIC LIEBETRAU Age, that they spent the first two-thirds of their lives looting the public [email protected] Fiction Editor only to spend the last third giving the money away. Now, writes politi- LAURIE MUCHNICK cal analyst and journalist Giridharadas, the global financial elite has [email protected] Children’s Editor reinterpreted Andrew Carnegie’s view that it’s good for society for VICKY SMITH [email protected] capitalists to give something back to a new formula: It’s good for busi- Young Adult Editor Claiborne Smith LAURA SIMEON ness to do so when the time is right, but not otherwise….A provocative [email protected] Staff Writer critique of the kind of modern, feel-good giving that addresses symptoms and not causes.” MEGAN LABRISE [email protected] Sweet Little Lies by Caz Frear (Aug. -

The Golden Bough (Vol. 1 of 2) by James George Frazer

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Golden Bough (Vol. 1 of 2) by James George Frazer This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Golden Bough (Vol. 1 of 2) Author: James George Frazer Release Date: October 16, 2012 [Ebook 41082] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GOLDEN BOUGH (VOL. 1 OF 2)*** The Golden Bough A Study in Comparative Religion By James George Frazer, M.A. Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge In Two Volumes. Vol. I. New York and London MacMillan and Co. 1894 Contents Dedication. .2 Preface. .3 Chapter I. The King Of The Wood. .8 § 1.—The Arician Grove. .8 § 2.—Primitive man and the supernatural. 13 § 3.—Incarnate gods. 35 § 4.—Tree-worship. 57 § 5.—Tree-worship in antiquity. 96 Chapter II. The Perils Of The Soul. 105 § 1.—Royal and priestly taboos. 105 § 2.—The nature of the soul. 115 § 3.—Royal and priestly taboos (continued). 141 Chapter III. Killing The God. 198 § 1.—Killing the divine king. 198 § 2.—Killing the tree-spirit. 221 § 3.—Carrying out Death. 233 § 4.—Adonis. 255 § 5.—Attis. 271 § 6.—Osiris. 276 § 7.—Dionysus. 295 § 8.—Demeter and Proserpine. 304 § 9.—Lityerses. 334 Footnotes . 377 [Transcriber's Note: The above cover image was produced by the submitter at Distributed Proofreaders, and is being placed into the public domain.] [v] Dedication. -

G. K. CHESTERTON the WISDOM of FATHER BROWN to LUCIAN

G. K. CHESTERTON THE WISDOM OF FATHER BROWN To LUCIAN OLDERSHAW CONTENTS 1. The Absence of Mr Glass 2. The Paradise of Thieves 3. The Duel of Dr Hirsch 4. The Man in the Passage 5. The Mistake of the Machine 6. The Head of Caesar 7. The Purple Wig 8. The Perishing of the Pendragons 9. The God of the Gongs 10. The Salad of Colonel Cray 11. The Strange Crime of John Boulnois 12. The Fairy Tale of Father Brown ONE The Absence of Mr Glass THE consulting-rooms of Dr Orion Hood, the eminent criminologist and specialist in certain moral disorders, lay along the sea-front at Scarborough, in a series of very large and well-lighted french windows, which showed the North Sea like one endless outer wall of blue-green marble. In such a place the sea had something of the monotony of a blue-green dado: for the chambers themselves were ruled throughout by a terrible tidiness not unlike the terrible tidiness of the sea. It must not be supposed that Dr Hood's apartments excluded luxury, or even poetry. These things were there, in their place; but one felt that they were never allowed out of their place. Luxury was there: there stood upon a special table eight or ten boxes of the best cigars; but they were built upon a plan so that the strongest were always nearest the wall and the mildest nearest the window. A tantalum containing three kinds of spirit, all of a liqueur excellence, stood always on this table of luxury; but the fanciful have asserted Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. -

High Flyer Lockheed Martin Moving F-16 Jet Production to S.C

IN SPORTS: Defending champ LMA softball returns plenty of experience for another title run B1 SCIENCE Arctic sea ice records new low for winter A6 FRIDAY, MARCH 24, 2017 | Serving South Carolina since October 15, 1894 75 cents Combating prison cellphones in prison, which corrections missioners how he was shot Ex-corrections directors across the country six times at his home early say is what they need to shut one morning in March 2010. down inmate cellphone use, “My doctor said I should be officer testifies once and for all. dead. ... Last Wednesday, I had But commissioners includ- surgery Number 24, but who’s in front of FCC ing Chairman Ajit Pai said the counting?” step was one that could hope- At the time, Johnson was COLUMBIA (AP) — Federal fully begin to combat the the lead officer tasked with officials took a step Thursday phones that officials say are keeping contraband items like toward increasing safety in the No. 1 safety issue behind tobacco, weapons and cell- prisons by making it easier to bars. phones out of Lee Correction- find and seize cellphones ob- The vote came after power- al Institution, a prison 50 tained illegally by inmates, ful testimony from Robert miles east of Columbia that voting unanimously to ap- Johnson, a former South Car- houses some of the state’s prove rules to streamline the olina corrections officer who most dangerous criminals. process for using technology was nearly killed in a shoot- The items are smuggled in- AP FILE PHOTO to detect and block contra- ing that authorities said was side, tossed over fences or Capt. -

An Historical Reading List for Children

1 2 The Story of Mankind Hendrik Willem Van Loon 2 The Story of Mankind Books iRead http://booksiread.org http://apps.facebook.com/ireadit http://myspace.com/ireadit The Story of Mankind by Hendrik van Loon December, 1996 [Etext #754] Scanned by Charles Keller with OmniPage http://booksiread.org 3 Professional OCR software purchased from Caere Corporation, 1-800-535-7226. Contact Mike Lough [email protected] Frontispiece caption = THE SCENE OF OUR HISTORY IS LAID UPON A LITTLE PLANET, LOST IN THE VASTNESS OF THE UNIVERSE. To JIMMIE “What is the use of a book with- out pictures?” said Alice. 4 The Story of Mankind FOREWORD For Hansje and Willem: WHEN I was twelve or thirteen years old, an uncle of mine who gave me my love for books and pictures promised to take me upon a mem- orable expedition. I was to go with him to the top of the tower of Old Saint Lawrence in Rot- terdam. And so, one fine day, a sexton with a key as large as that of Saint Peter opened a mysteri- ous door. “Ring the bell,” he said, “when you come back and want to get out,” and with a great grinding of rusty old hinges he separated 5 6 The Story of Mankind us from the noise of the busy street and locked us into a world of new and strange experiences. For the first time in my life I was confronted by the phenomenon of audible silence. When we had climbed the first flight of stairs, I added another discovery to my limited knowledge of natural phenomena–that of tangible darkness. -

Wreaths of Time: Perceiving the Year in Early Modern Germany (1475-1650)

Wreaths of Time: Perceiving the Year in Early Modern Germany (1475-1650) Nicole Marie Lyon October 12, 2015 Previous Degrees: Master of Arts Degree to be conferred: PhD University of Cincinnati Department of History Dr. Sigrun Haude ii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT “Wreaths of Time” broadly explores perceptions of the year’s time in Germany during the long sixteenth century (approx. 1475-1650), an era that experienced unprecedented change with regards to the way the year was measured, reckoned and understood. Many of these changes involved the transformation of older, medieval temporal norms and habits. The Gregorian calendar reforms which began in 1582 were a prime example of the changing practices and attitudes towards the year’s time, yet this event was preceded by numerous other shifts. The gradual turn towards astronomically-based divisions between the four seasons, for example, and the use of 1 January as the civil new year affected depictions and observations of the year throughout the sixteenth century. Relying on a variety of printed cultural historical sources— especially sermons, calendars, almanacs and treatises—“Wreaths of Time” maps out the historical development and legacy of the year as a perceived temporal concept during this period. In doing so, the project bears witness to the entangled nature of human time perception in general, and early modern perceptions of the year specifically. During this period, the year was commonly perceived through three main modes: the year of the civil calendar, the year of the Church, and the year of nature, with its astronomical, agricultural and astrological cycles. As distinct as these modes were, however, they were often discussed in richly corresponding ways by early modern authors. -

September 29, 2019

The Twenty-Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time September 29, 2019 Use Green Guide marks to place cover photo over this text box. Size of Cover Photo should be 7.33” H x 7.5” W. St. Mary Immaculate Parish 15629 S. Rt. 59, Plainfield, IL 60544-2695 Parish Office: 815-436-2651 School Office: 815-436-3953 Religious Ed. Office: 815-436-4501 Confirmation Office: 815-436-2861 www.smip.org .com/StMaryImmaculate @SMIPlainfield @SMIPlainfield What’s Inside Mass Intentions The Word from Fr. Pat...................................... 3 Monday— September 30, 2019 7:30 a.m. Denny & Lois Alcamo—(Helen Farcus) La Palabra de Padre Pat ................................ 3-4 Słowo od Ojca Pat ............................................. 4 Tuesday— October 1, 2019 7:30 a.m. Bernie Lepacek—(K of C Good Shepherd Council) Capital Campaign Survey ............................ 5-6 Adoracion Patolot—(Patolot Family) Crash Course in Catholicism .......................... 7 Wednesday — October 2, 2019 Our Family in Faith ..................................... 8-15 7:30 a.m. Jim Mander—(John & Lu DeLauriea) Recurring Meetings Prayer Cross Thursday— October 3, 2019 In Memoriam 7:30 a.m. Lorrie Blazina—(SMI Seniors Group) Newly Baptized New Parishioners Teofista & Maryrose Munsayac—(Munsayac Family) Parking Lot Renovations Friday— October 4, 2019 CCW Meeting Paint & Pray—FIAT 7:30 a.m. Seminarian Pancake Breakfast 8:45 a.m. (School Mass) Charles Kramer—(Wife Catherine & Family) Formed.org Pick of the Week Blessing of the Animals Saturday— October 5, 2019 First Saturday Devotion 7:30 a.m. Ramon Loyola—(Family) Healing Prayer Service 4:00 p.m. Mary Singleton—(Tom & Margaret O’Connell) 40 Days for Life Prayer Vigil 5:30 p.m. -

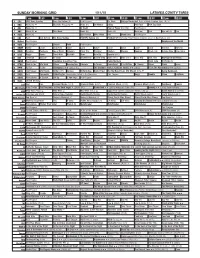

Sunday Morning Grid 1/11/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/11/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Dr. Chris College Basketball Duke at North Carolina State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) On Money Skiing PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football NFC Divisional Playoff Dallas Cowboys at Green Bay Packers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Employee of the Month 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Revenge of the Nerds 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Pablo Montero Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa: Performed Under the Direction and Patronage of the African Association, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797

Travels in the interior districts of Africa: performed under the direction and patronage of the African association, in the years 1795, 1796, and 1797 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.CH.DOCUMENT.sip100017 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Travels in the interior districts of Africa: performed under the direction and patronage of the African association, in the years 1795, 1796, and 1797 Author/Creator Park, Mungo Date 1799 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Middle Niger, Mali, Timbucktu Source Smithsonian Institution Libraries, DT356 .P236 1799 Description LIST OF VOLUMES IN HERBERT STRANG'S LIBRARY. -

The Robbers - a Tragedy

The Robbers - A Tragedy Frederich Schiller The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Robbers, by Frederich Schiller This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: The Robbers A Tragedy Author: Frederich Schiller Release Date: December 8, 2004 [EBook #6782] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ROBBERS *** Produced by David Widger THE ROBBERS. By Frederich Schiller SCHILLER'S PREFACE. AS PREFIXED TO THE FIRST EDITION OF THE ROBBERS PUBLISHED IN 1781. Now first translated into English. This play is to be regarded merely as a dramatic narrative in which, for the purpose of tracing out the innermost workings of the soul, advantage has been taken of the dramatic method, without otherwise conforming to the stringent rules of theatrical composition, or seeking the dubious advantage of stage adaptation. It must be admitted as somewhat inconsistent that three very remarkable people, whose acts are dependent on perhaps a thousand contingencies, should be completely developed within three hours, considering that it would scarcely be possible, in the ordinary course of events, that three such remarkable people should, even in twenty-four hours, fully reveal their characters to the most penetrating inquirer. A greater amount of incident is here crowded together than it was possible for me to confine within the narrow limits prescribed by Aristotle and Batteux. It is, however, not so much the bulk of my play as its contents which banish it from the stage. -

Representations of the Witch in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Women’S Writing

Bedlam and Broomsticks: Representations of the Witch in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Women’s Writing Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sarah Bruton October 2006 School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University UMI Number: U584115 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584115 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being currently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed __________________________________ (candidate) Date _____ Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed (candidate) Date Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed _________ (candidate) Date ii Abstract This thesis is about representations of witches in texts by women writers, and how they develop over time.