They Say in Harlan County

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samoan Submission Machines

Samoan Submission Machines: Grappling with Representations of Samoan Identity in Professional Wrestling Theo Plothe1 Savannah State University [email protected] Amongst the myriad of characters to step foot in the squared circle, perhaps no ethnic group has been as celebrated or marginalized as the Samoans who have made their names in professional wrestling. The discussion of Samoan identity in the context of sport has examined Maori identity and masculinity in New Zealand, among other topics, but there has yet to be work which considers Samoans within professional wrestling. This research investigates Samoan identity through a content analysis of televised wrestling matches. This research identifies six primary stereotypes under which Samoan identity is portrayed. These portrayals of Samoan characters, I argue, flatten the representation of this ethnic group within wrestling and culture at large. Keywords: Samoans, identity, representation, gimmicks Introduction Among the myriad of characters to step foot in the squared circle, perhaps no ethnic group has been as celebrated or marginalized as the Samoans who have made their names in professional wrestling. This research investigates the identity of Samoans within professional wrestling, and the different ways they are constructed and presented to audiences. “Gimmicks,” characters portrayed by a wrestler “resulting in the sum of fictional elements, attire and wrestling ability” (Oliva and Calleja 3) utilized by Samoans have run the gamut from the wild uncivilized savage, to the sumo (both in villainous Japanese and comically absurd iterations), to the ultra-cool mogul who wears silk shirts and fancy shoes. Their ability to cut promos, an important facet of the modern gimmick allowing wrestlers to address their opponents and storylines, varies widely as well, but all lie within their Samoan identity. -

Estrategias, Passwords, Códigos Y Consejos De La

TRUCOS A-Z PlayStation 3 TrucosESTRATEGIAS, PASSWORDS, CÓDIGOS Y CONSEJOSPS3 DE LA A A LA Z No te muevas de la esquina don- 05 CHINA Los colores que debes recordar ARMORED CORE 4 de empieza el pasillo. Regresa • M1: en la edificación gemela a son los siguientes, toma nota: • Puntos FRS fáciles: al ascensor y deja que Hicks te la que esconde el primer panel, Blanco: aldeano cotidiano del )A Si quieres conseguir puntos FRS cuente la localización de las ca- pero al otro lado del canal, en que podrás obtener información. completa el modo normal y si- bezas químicas. un rincón. Amarillo: objetivo de asesinato. ALONE mulador. • M3: nada más encontrar a • M2: en la casa que hay a la iz- Rojo: soldado. IN THE DARK Selecciona el modo difícil y com- Hicks, gira a la izquierda y ve quierda del cobertizo de pla- Azul: aliado. CONSEJOS pleta una misión con un rango in- hasta el fondo del pasillo, para cas metálicas azules, en el se- • Utiliza la visión especial: ferior a S. dar con la maleta metálica pe- gundo piso. El agente Edward Carnby puede Vuelve a jugar la misma misión gada a la pared de la derecha. • M3: tras el contenedor de co- utilizar su percepción con R3 pa- en dificultad normal y logra el IRAQ lor verde que hay al fondo del ra destacar elementos que pue- rango S. Conseguirás un punto • M1: justo antes de abandonar todo, justo donde el helicóptero den ser importantes. FRS rápidamente. Vuelve a jugar el primero de los bunker donde deja caer a los soldados del ejér- Si ves que andas un poco perdi- todas las misiones que no tengas entras (y antes de volar el heli- cito chino. -

Chemical and Physical Structural Studies on Two Inertinite-Rich Lump

CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL STRUCTURAL STUDIES ON TWO INERTINITE-RICH LUMP COALS. Nandi Malumbazo A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philoso- phy in the School of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand. Johannesburg, 2011 DECLARATION I, Nandi Malumbazo, declare that the thesis entitled: “CHEMICAL AND PHYSICAL STRUCTURAL STUDIES ON TWO INER- TINITE-RICH LUMP COALS” is my own work and that all sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and ac- knowledged by means of references. Signature: ……………………………………………………………….. Date:………………………………………………………………………… Page i ABSTRACT ABSTRACT Two Highveld inertinite-rich lump coals were utilized as feed coal samples in order to study their physical, chemical structural and petrographic variations during heat treat- ment in a packed-bed reactor unit combustor. The two feed lump coals were selected as it is claimed that Coal B converts at a slower rate in a commercial coal conversion process when compared to Coal A. The reason for this requires detailed investigation. Chemical structural variations were determined by proximate and coal char CO2 reactiv- ity analysis. Physical structural variations were determined by FTIR, BET adsorption methods, XRD and 13C Solid state NMR analysis. Carbon particle type analysis was con- ducted to determine the petrographic constituents of the reactor generated samples, their maceral associations (microlithotype), and char morphology. This analysis was undertaken with the intention of tracking the carbon conversion and char formation and consumption behaviour of the two coal samples within the reactor. Proximate analysis revealed that Coal A released 10 % more of its volatile matter through the reactor compared to Coal B. -

The Consequences of Appalachian Representation in Pop Culture

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--English English 2017 STRANGERS WITH CAMERAS: THE CONSEQUENCES OF APPALACHIAN REPRESENTATION IN POP CULTURE Chelsea L. Brislin University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.252 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brislin, Chelsea L., "STRANGERS WITH CAMERAS: THE CONSEQUENCES OF APPALACHIAN REPRESENTATION IN POP CULTURE" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--English. 59. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/english_etds/59 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the English at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--English by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

The Coal Mining Heritage of Lafayette

The Coal Mining Heritage of Lafayette From the late I 880s until the I 930s, Lafayette was a major coal town. Read the history of the coal mining era, examine the location of coal mines within the Lafayette area, and enjoy historic photos of the Waneka Lake Power Plant and the Simpson Mine with the attached Coal Mines of the Lafaveti’e Area brochure. This brochure was created by the Lafayette Historic Preservation board, and it highlights the fascinating Coal Mining Heritage of Lafayette. oft/ic — • Coal Mines Lafayette Area page 1 • Coal Mines of the Lafayette Area - page 2 • Coal Mines f the Lfa)’ette Area — map ____________________________ Historic Preservation Board, City of Lafayette, Colorado The social legacy. The social legacy of mining is equally important to contemporary Lafayette The mines required far more labor than was available locally and quickly attracted experienced miners and laborers from Europe and other parts of the U.S. The result was a community comprised of many ethnic groups, including Welsh, English. Scottish, Irish, central European, Hispanic, Italian, and Swedish workers and their families. Local farmers and ranchers also shared in the coal boom and worked as miners in the winter when coal production was high and agricultural work slow. A sense of this ethnic diversity can be gained by walking through the Lafayette cemetery at Baseline and 111th Street. The variety of family names gives a sense of the many nationalities that have contributed to Lafayette’s history. Although the mining life was hard, families were fun-loving and many social activities centered around schools and churches. -

The Hickston Hog®

Page 6 THE HICKSTON HOG® TM THE HICKSTON HOG® Page 7 PART 1 The Adult Redneck Daily Tuesday, April 1, 1999 WE’RE NOT ALONE! HICKSTON INVADED! A Paranormal Interview With Leonard hick. Ventura: Clones? Are We Being Invaded? You Be The Judge. Leonard: That’s the name.Clones.First clue we got was when a whole pack of Ventura: So, tell us what exactly ‘em tried t’run us down on the happened that day, Mister...uh... roundabout; ya cain’t be none too Leonard: Leonard. Jes’ Leonard. careful ‘bout steppin’ out inta the Ventura: Yeah, okay, Leonard. middle’a the road ‘round these parts, Leonard: It all started when them not even on a good day.Billy Ray warn’t aliens took our pig Bessie. There was the only one they snagged, neither. this light, y’see, an’ then she was gone. Them aliens got aholda the skinny ol’ She was the best hog in the county,too coot from up the hill,‘n’ Sheriff Hobbes — jes’ won $250 at the fair. Me an’ — other folks too, but those were the Bubba, we was on our way home at the worst. Dozens of ‘em all over the place, time.We was pretty well liquored up at armed an’ mean an’ lookin’ around with that point, celebratin’ y’know, an’ then beady lil’ alien eyes.Took a good couple they busted our pickup an’ took her dead-on shots to take ‘em down. away. [pantomimes aiming and firing, with great relish] I tell ya, after the first few Ventura: They...? it was almost fun. -

282 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER #282 COUNTY SALES P.O. Box 191 November-December 2006 Floyd,VA 24091 www.countysales.com PHONE ORDERS: (540) 745-2001 FAX ORDERS: (540) 745-2008 WELCOME TO OUR COMBINED CHRISTMAS CATALOG & NEWSLETTER #282 Once again this holiday season we are combining our last Newsletter of the year with our Christmas catalog of gift sugges- tions. There are many wonderful items in the realm of BOOKs, VIDEOS and BOXED SETS that will make wonderful gifts for family members & friends who love this music. Gift suggestions start on page 10—there are some Christmas CDs and many recent DVDs that are new to our catalog this year. JOSH GRAVES We are saddened to report the death of the great dobro player, Burkett Graves (also known as “Buck” ROU-0575 RHONDA VINCENT “Beautiful Graves and even more as “Uncle Josh”) who passed away Star—A Christmas Collection” This is the year’s on Sept. 30. Though he played for other groups like Wilma only new Bluegrass Christmas album that we are Lee & Stoney Cooper and Mac Wiseman, Graves was best aware of—but it’s a beauty that should please most known for his work with Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs, add- Bluegrass fans and all ing his dobro to their already exceptional sound at the height Rhonda Vincent fans. of their popularity. The first to really make the dobro a solo Rhonda has picked out a instrument, Graves had a profound influence on Mike typical program of mostly standards (JINGLE Auldridge and Jerry Douglas and the legions of others who BELLS, AWAY IN A have since made the instrument a staple of many Bluegrass MANGER, LET IT bands everywhere. -

References for Chapters 7-9, 11

REFERENCES Adams, L.M., J.P. Capp and D.W. Gillmore. 1972. Coal mine spoil and refuse bank reclamation. In: Third Mineral Waste Utilization Symposium. Chicago, IL. Adriano, D.C., A.L. Page, A.A. Elseewi, A.C. Chang, and I. Straughan. 1980. Utilization and disposal of fly ash and other coal residues in terrestrial ecosystems: A review. Journal of Environmental Quality. 9:333-344. Adriano, D.C., T.A. Woodford and T.G. Ciravolo. 1978. Growth and elemental composition of corn and bean seedlings as influenced by soil application of coal ash. Journal of Environmental Quality. 7:416-421. Allison, J.D., D.S. Brown and K.J. Novo-Gradac. 1992. MINTEQA2, Geochemical Assessment Model for Environmental Systems. Version 3, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Arndt, H.H. 1971. Geological Map of the Mount Carmel Quadrangle. Columbia, Northumberland and Schuylkill Counties, Pennsylvania. Map GQ-919. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey. Ash, S.H. and W.L. Eaton. 1947. Barrier pillars in the anthracite region of Pennsylvania. Am. Inst. Min. and Met. Eng. Tech. Pub. 2289. 20pp. Ash, S.H. 1950a. Buried valley of the Susquehanna River. U.S. Bureau of Mines Bull. 494, 27 pp. Ash, S.H. 1950b. Data on pumping at the Anthracite mines of Pennsylvania. U.S. Bureau of Mines R.I. 4700, 264 pp. Ash, S.H., E.W. Felegy, D.O. Kennedy and P.S. Miller. 1951. Acid-Mine-Drainage Problems. Anthracite Region of Pennsylvania. U.S. Bureau of Mines, Bull. 508, 72 pp. Ash, S.H., B.S. Davies, H.E. -

Bridging the Digital Divide in Rural Appalachia: Internet Usage in the Mountains Jacob J

Informing Science InSITE - “Where Parallels Intersect” June 2003 Bridging the Digital Divide in Rural Appalachia: Internet Usage in the Mountains Jacob J. Podber, Ph.D. Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA [email protected] Abstract This project looks at Internet usage within the Melungeon community of Appalachia. Although much has been written on the coal mining communities of Appalachia and on ethnicity within the region, there has been little written on electronic media usage by Appalachian communities, most notably the Melun- geons. The Melungeons are a group who settled in the Appalachian Mountains as early as 1492, of apparent Mediterranean descent. Considered by some to be tri-racial isolates, to a certain extent, Melungeons have been culturally constructed, and largely self-identified. According to the founder of a popular Me- lungeon Web site, the Internet has proven an effective tool in uncovering some of the mysteries and folklore surrounding the Melungeon community. This Web site receives more than 21,000 hits a month from Melungeons or others interested in the group. The Melungeon community, triggered by recent books, films, and video documentaries, has begun to use the Internet to trace their genealogy. Through the use of oral history interviews, this study examines how Melungeons in Appalachia use the Internet to connect to others within their community and to the world at large. Keywords : Internet, media, digital divide, Appalachia, rural, oral history, ethnography, sociology, com- munity Introduction In Rod Carveth and Susan Kretchmer’s paper “The Digital Divide in Western Europe,” (presented at the 2002 International Summer Conference on Communication and Technology) the authors examined how age, income and gender were predictors of the digital divide in Western Europe. -

KEM.C.GUNN IK.OWENS)Kern 79

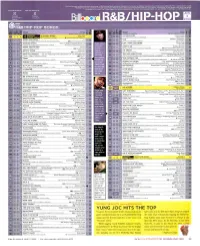

The most popular singles and tracks, acccrding to R813/110Hop iedi.4 audience impressions measured by Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems and sales datafrom a subset pane of aye RSEfil-lip-Hop stores compiled by Nie scn Souncszan.3reateSt Game, Sales and Greatest Gainer;IAErplay are awarded, respectively. tot the largest retail sales and airplay increases on the chart. Sm. Charts Lagaid for ruin od explanations. ei 2006. VNU Business Media, Inc. and Nielsen SoundScan, Inc. Allrights resene.' /JIRO TIONI-DRED lo SALES DATA COMPILED BY JUN Nelsen Nielsen 3 Snack -am P SoundSi..en 2- 2 System 41° 2006 1101. 13 &B /HIP -HOP SONGS Artist TITLE IMPRINT/PROMOTION LABEL e PRODUCER (SO I'M GONNA BE Donell Jones ' 1619EATE$T ITS Gm; DOWN Vung Joc 8 3 3 16 LAFACE/ZOEMIA 911.11011 pill0L9TNIT71 (IROBINSON,C.MOORE) Q BLOCK/BN) BOY SOUTH/ATLANTIC TIM a BOB (D JONES,T.KELLEY.B.ROBINSON) YOU Raheem DeVaughn WHAT YOU KNOW 8 55, 16 T.HUNTER (R.S.DEvAUGHN.T.HUNTER) 0 JIVE/20mA DJ TOOMP C.HARRIS,A.DAVIS.C.MAYEIELD,L.HUTSON,O.HATHAWAY) 00 GRAND HUSTLE/ATLANTIC ENOUGH CRYIN Mary J. Blige Featuring Brook-lyn ,{CANI TAKE YOU HOME Jamie Foxx - 3 ID Singer, wl-o ;s 0 J/RMG 411 R.JERKINS (M IBLIGE.R.JERKINS,S.GARRETT.S.C.CARTER) Co MATRIARN/GEFTEN/INTERSCOPE TIMBALAND (T.v.MOSLEY,S.GARRETT) set to opei Bubba Spanoot WHEN YOU'RE MAD Ne-Yo HEAT IT UP 59 I MR.COLLIPARK (W.mATHISN.CROOmS.S.ANDERSON) 00 NEW SOUTH/PURPLE RIBBONNIRGiN S.TAYLOR (S.SM1TH,S.TAYLOR) 00 DEE JAM/IONG for Mary Gucci Mane Featuring Mac Bre-Z GETT1N' SOME Shawnna Blige on GO AHEAD 57 5 6 $768 0 LATLARE/BIG -

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 21 Johnny Cash & Carl

名前 アーティスト アルバム ジャンル 分 年 21 Johnny Cash & Carl Perkins The First Years/The Heart And Soul Of Carl Perkins カントリー 3.4 1755 Steve Riley & The Mamou Playboys Live! カントリー 3.0 1929 Merle Haggard Chill Factor Country 3.6 1987 1976 Alan Jackson Good Time Country & Folk4.2 2008 1999 The Wilkinsons Here And Now カントリー 3.5 2000 (A Day In The Life Of A) Single Mother Victoria Shaw In Full View Country & Folk3.1 1995 (A Day In The Life Of A) Single Mother Victoria Shaw In Full View (P) 1995 カントリー 3.1 1995 (After Sweet Memories) Play Born To Lose Again Ronnie Milsap The Golden Country Hits 15 Green,Green Grass Of Home カントリー 3.0 (Blank Track) Dixie Chicks Fly カントリー 0.1 2001 (Ghost) Riders In The Sky Johnny Cash The Essential Johnny Cash (Disc 2) カントリー 3.7 2002 (Give It To) The Needy Mary Lee's Corvette 700 Miles Rock 4.3 2003 (Give It To) The Needy Mary Lee's Corvette 700 Miles ロック 4.3 2003 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyB.J. Wrong Thomas Song Greatest Hits- B. J. Thomas ロック 3.4 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyB.J.Thomas Wrong Song The Golden Country Hits 11 I Fall To Pieces カントリー 3.4 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyBillie Wrong Jo Spears Song The Ultimate Collection Country & Folk3.3 1975 (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done SomebodyThe Wrong Golden Song Country Hits 550 The Golden Country Hits Sing Along -Special Karaoke Best 51-(Ii) Country & Folk3.5 (I Can't Help You) I'm Falling Too Skeeter Davis RCA Country Hall Of Fame カントリー 2.8 (I Never Promised You A) Rose Garden Billie Jo Spears -

Labor Songs: the Provocative Product of Psalmists, Prophets, and Poets

Journal of Catholic Legal Studies Volume 50 Number 1 Volume 50, 2011, Numbers 1&2 Article 12 Labor Songs: The Provocative Product of Psalmists, Prophets, and Poets Raymond A. Franklin David L. Gregory Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcls Part of the Catholic Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Catholic Legal Studies by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LABOR SONGS: THE PROVOCATIVE PRODUCT OF PSALMISTS, PROPHETS, AND POETS RAYMOND A. FRANKLINt & DAVID L. GREGORY* The words of the prophets are written on subway walls and tenement halls. "The Sounds of Silence," Simon & Garfunkel' [The Rolling Stones are] the most dangerous rock-and-roll band in the world. Life, Keith Richards and James Fox2 A singing movement is a winning movement.3 Attributed to, inter alia, Pete Seeger 4 and Utah Phillips' Associate, Sapir and Frumkin; J.D., 2010, Dean's Fellow, St. John's University School of Law; B.A., 2001, Villanova University. * Dorothy Day Professor of Law and Executive Director of the Center for Labor and Employment Law, St. John's University School of Law; J.S.D., 1987, Yale University; L.L.M., 1982, Yale University; J.D., magna cum laude, 1980, University of Detroit Law School; M.B.A., Labor Relations, 1977, Wayne State University Graduate School of Business; B.A., cum laude, 1973, The Catholic University of America School of Philosophy.