Historical Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

Drainage on Evolving Fold-Thrust Belts: a Study of Transverse Canyons in the Apennines W

Basin Research (1999) 11, 267–284 Drainage on evolving fold-thrust belts: a study of transverse canyons in the Apennines W. Alvarez Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of California, Berkeley, USA, and Osservatorio Geologico di Coldigioco, 62020 Frontale di Apiro (MC), Italy ABSTRACT Anticlinal ridges of the actively deforming Umbria–Marche Apennines fold-thrust belt are transected by deep gorges, accommodating a drainage pattern which almost completely ignores the presence of pronounced anticlinal mountains. Because the region was below sea level until the folds began to form, simple antecedence cannot explain these transverse canyons. In addition, the fold belt is too young for there to have been a flat-lying cover from which the rivers could have been superposed. In 1978, Mazzanti & Trevisan proposed an explanation for these gorges which deserves wider recognition. They suggested that the Apennine fold ridges emerged from the sea in sequence, with the erosional debris from each ridge piling up against the next incipient ridge to emerge, gradually extending the coastal plain seaward. The new coastal plain adjacent to each incipient anticline provided a flat surface on which a newly elongated river could cross the fold, positioning it to cut a gorge as the fold grew. Their mechanism is thus a combination of antecedence and superposition in which folds, overlying sedimentary cover and downstream elongations of the rivers all form at the same time. A study of Apennine drainage, using the sequence of older-to-younger transected Apennine folds as a proxy for the historical evolution of drainage cutting through a single fold, shows that transverse drainage forms when sedimentation dominates at the advancing coastline. -

Comuni Del Candigliano

Acqualagna Apecchio Piobbico Piano d’Azione per l’Energia Sostenibile Comuni del Candigliano Hemos firmado! Wij hebben ondertekend! Abbiamo firmato! Iffirmajna! Realizzato da: Coordinatore Territoriale: Provincia di Pesaro e Urbino Servizio 10 – Rischio Sismico, ambientale, Agricoltura, Fonti rinnovabili – Pianificazione ambientale Ing.. Fabrizio Montoni - Dirigente del Servizio 10 Dott.ssa Alessandra Traetto - Ufficio 10.1.4 Valorizzazione del patrimonio naturalistico, Progetti per la sostenibilità, Educazione ambientale (Labter – CEA) Redazione PAES e Supporto tecnico: Società Megas. Net S.p.A. Alighiero Omicioli: Amministratore Unico Arch. Marica Derosa: Ufficio tecnico Arch. Silvia Cecchini: Ufficio tecnico Con la collaborazione di: Comune di Acqualagna: Sindaco Andrea Pierotti, Ing. A. Iodio, Sig. R. Lupini e Geom. M. Postiglioni Comune di Apecchio: Sindaco Vittorio Alberto Nicolucci e Sig. Palmiro Rossi, Geom. Massimo Pazzaglia e Geom E. Biccari Comune di Piobbico: Sindaco Giorgio Mochi, Geom. Lamberto Merendoni e Geom. Trufelli Con la supervisione di: Agenzia per l’Energia e lo Sviluppo Sostenibile di Modena – A.E.S.S. Dott.ssa Claudia Carani Data di emissione 25 Febbraio 2016 2 INDICE 1. PATTO DEI SINDACI .................................................................................................... 5 2. IL TERRITORIO .......................................................................................................... 9 3. STRATEGIA ............................................................................................................ -

List of Rivers of Italy

Sl. No Name Draining Into Comments Half in Italy, half in Switzerland - After entering Switzerland, the Spöl drains into 1 Acqua Granda Black Sea the Inn, which meets the Danube in Germany. 2 Acquacheta Adriatic Sea 3 Acquafraggia Lake Como 4 Adda Tributaries of the Po (Left-hand tributaries) 5 Adda Lake Como 6 Adige Adriatic Sea 7 Agogna Tributaries of the Po (Left-hand tributaries) 8 Agri Ionian Sea 9 Ahr Tributaries of the Adige 10 Albano Lake Como 11 Alcantara Sicily 12 Alento Adriatic Sea 13 Alento Tyrrhenian Sea 14 Allaro Ionian Sea 15 Allia Tributaries of the Tiber 16 Alvo Ionian Sea 17 Amendolea Ionian Sea 18 Amusa Ionian Sea 19 Anapo Sicily 20 Aniene Tributaries of the Tiber 21 Antholzer Bach Tributaries of the Adige 22 Anza Lake Maggiore 23 Arda Tributaries of the Po (Right-hand tributaries) 24 Argentina The Ligurian Sea 25 Arno Tyrrhenian Sea 26 Arrone Tyrrhenian Sea 27 Arroscia The Ligurian Sea 28 Aso Adriatic Sea 29 Aterno-Pescara Adriatic Sea 30 Ausa Adriatic Sea 31 Ausa Adriatic Sea 32 Avisio Tributaries of the Adige 33 Bacchiglione Adriatic Sea 34 Baganza Tributaries of the Po (Right-hand tributaries) 35 Barbaira The Ligurian Sea 36 Basentello Ionian Sea 37 Basento Ionian Sea 38 Belbo Tributaries of the Po (Right-hand tributaries) 39 Belice Sicily 40 Bevera (Bévéra) The Ligurian Sea 41 Bidente-Ronco Adriatic Sea 42 Biferno Adriatic Sea 43 Bilioso Ionian Sea 44 Bisagno The Ligurian Sea 45 Biscubio Adriatic Sea 46 Bisenzio Tyrrhenian Sea 47 Boesio Lake Maggiore 48 Bogna Lake Maggiore 49 Bonamico Ionian Sea 50 Borbera Tributaries -

Climate and Land Use Changes As Origin of the Water Cycle Variations

DOI: 10.7343/as-2016-207 Special Issue AQUA2015 - Paper Climate and land use changes as origin of the Water Cycle variations and sediment transport in Pesaro Urbino Province, Central and Eastern Italy Cambiamenti climatici e dell’uso del suolo come origine delle variazioni del Ciclo dell’Acqua e del trasporto dei sedimenti nella Provincia di Pesaro Urbino, Italia Centro-orientale Daniele Farina, Paolo Cavitolo Riassunto: Lo studio evidenzia una diminuzione significati- Abstract: The study shows a significant net precipitation and surfi- va delle precipitazioni efficaci e del deflusso durante il periodo cial runoff decrease in the Province of Pesaro-Urbino during the 1950- 1950-2010, che riguarda in particolare le stazioni montane ed il 2010 period, especially affecting mountain areas and the water-surplus periodo invernale di surplus idrico. La variazione di deflusso è winter season. Runoff variation is also related to a significant land collegata anche ad una importante evoluzione dell’uso del suolo use change, due to a progressive natural reafforestation process that has nelle aree montane, a causa di un progressivo processo di naturale taken place in the mountain area. Candigliano river’s base-flow, fed rimboschimento. Il Flusso di base del f. Candigliano, alimentato by carbonate aquifers’ groundwater discharge, was found more stable dalla discarica sorgiva degli acquiferi carbonatici, è risultato più over time, due to an aquifers’ capacity largely exceeding that of existing stabile, per effetto di una capacità degli acquiferi largamente su- surface reservoirs. The latter have been affected by a significant silting periore a quello delle acque invasate nei bacini superficiali. Tali process, which is still active, as suggested by specific erosion rates of wa- invasi sono soggetti ad un marcato processo di interrimento, che tersheds, particularly in the Foglia basin. -

Piobbico Sant’Angelo Ado

Piobbico Sant’Angelo ado Piano Castello dei Pecorari Le Ville Ca Meschio Piobbico Castiglione Monteforno Santa Maria in Val d’Abisso Apecchio Urbania Castello dei Pecorari ille Piobbico Rocca Leonella Santa Maria al d’Abisso Cardella Piobbico scheda 10 Veduta invernale della cittadina di Piobbico. Piobbico: Balza della Penna. 84 Piobbico Piobbico Il senso del luogo iobbico è un vascello, un vascello fantasma che veleggia nel terri- torio della provincia di Pesaro e Urbino. Una nave però ancora in Pperfetto stato: non ha vele sdrucite, falle nella chiglia e àncora arrugginita. La sua prua alta, fiera, è la torre portaia del castello Brancaleoni, la sua vela, immensa e stagliata contro il cielo è il monte Nerone, il Biscubio e il Candigliano, che qui s’incrociano, i suoi remi. La bandiera è piratesca, e Piobbico è una mina vagante di arte e cultura pronta a conquistare l’animo del visitatore in un rapido ed inaspettato arrembaggio. scheda 10 Un vascello fantasma poiché ancora in pochi conoscono questo pic- colo feudo adagiato tra le montagne, luogo che tra Quattro e Cinquecento fu corte rinascimentale della famiglia Brancaleoni. Piobbico, il paese che non ti aspetti e che ti schiaffeggia con la sua bellezza. È oltre Acqualagna questo centro, oltre la chiusa costituita dal castel- lo di Naro e da quello di Frontino. Lasciando Acqualagna e dirigendosi verso Piobbico, per un breve tratto, si abbandona, in parte, la civiltà moderna. La strada che prima godeva di una buona vista sulla valle posta tra la gola del Furlo e quella del Burano ora diviene piccola piccola. -

Pae

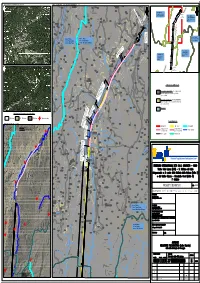

Riprese fotografiche dell'area a volo d'uccello 3ODQLPHWULDFRQOH8QLWjGLSDHVDJJLRVXFDUWDJUDILD6F Regione: Marche Mercatello Provicia: Pesaro Urbino Svincolo 2 Comune: Borgo Pace Nuova Regione: Marche realizzazione Provicia: Pesaro Urbino Comune: Mercatello sul Mercatello Metauro Regione: Marche Regione: Marche Regione: Marche Provicia: Pesaro Urbino Provicia: Pesaro Urbino Comune: Apecchio Provicia: Pesaro Urbino Svincolo 2 - Lato Marche Tratto realizzato soggeto a Comune: Borgo Pace Comune: Mercatello sul Metauro interventi per la messa in esercizio Regione: Umbria Provicia: Perugia L=52 m Regione: Umbria Comune: Citta di Viadotto La Pieruccia Provicia: Perugia Castello Comune: San Giustino Svincolo 1 Nuova Grosseto realizzazione Torrente S.ANTONIO /HJHQGD8QLWjILVLRJUDILFKH Aree montuose appenniniche. Aree a quote elevate con molte tipologie di valli strette e gli alvei in L=654 m genere confinati Galleriaa sezione S. circolare Antonio Galleria artificiale S. Antonio Aree collinari appenniniche. Aree frequentemente a dolce morfologia. La valli sono piuttosto ampie e gli alvei meno confinati Alta pianura Morfologia del Paesaggio: fasce altimetriche L=180 m Viadotto Sorgente xxx <600 mt slm 600 - 700 mt slm >700 mt slm Quote altimetriche L=60 m Legenda generale Planimetria su DEM, Sc. 1:20.000 Galleriaa sezioneartificiale circolare S. Veronica Dn 5.20 REGIONE: MARCHE PROVINCIA: PESARO URBINO L=161 m Viadotto Valpiana L=230 m Torrente CANDIGLIANO Galleria Valpiana Torrente S.ANTONIO Galleria naturale Valpiana a sezione circolare Dn 5.20 L=27.25 m Ponte Guinza PROGETTO DEFINITIVO AN58 PROGETTAZIONE: Torrente CANDIGLIANO Regione: Marche Provicia: Pesaro Urbino Comune: Mercatello sul Metauro Regione: Umbria Provicia: Perugia Comune: Citta di Castello 800 750 700 750 650 Fosso 800 700 850 700 750 Fonte 950 850 del 900 700 800 Imbrusca 189 955.00 750 850 700 800 Val 750 850 L O7 0 2M D 1 8 0 1 750 750 700 di 800 D 750 900 800 800 700 C 850 Fosso B REGIONE: UMBRIA 950 800 PROVINCIA: PERUGIA Sorcio 750 950 A REV. -

User-Oriented Hydrological Indices for Early Warning System. Validation Using Post-Event Surveys: Flood Case Studies on the Central Apennines District

https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-2020-296 Preprint. Discussion started: 31 July 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. User-oriented hydrological indices for early warning system. Validation using post-event surveys: flood case studies on the Central Apennines District. Annalina Lombardi1, Valentina Colaiuda1,2, Marco Verdecchia2 and Barbara Tomassetti1 5 1CETEMPS, Centre of Excellence University of L’Aquila, via Vetoio, 67010 Coppito (L’Aquila), Italy 2Department of Physical and Chemical Sciences, University of L’Aquila, via Vetoio, 67010 Coppito (L’Aquila) Italy Correspondence to: Annalina Lombardi ([email protected]) Abstract. Flood and flash floods are complex events, depending on weather dynamics, basin physiographical characteristics, land use cover and water management. For this reason, prediction of such events usually deals with very accurate model tuning 10 and validation, which is usually site-specific and based on climatological data, such as discharge time series or flood databases. In this work, we developed and tested two hydrological stress indices for flood detection in the Central Italy Apennine District: a heterogeneous geographical area, characterized by complex topography and medium-to-small catchment extension. Proposed indices are threshold-based and developed taking into account operational requirements of civil protection end-users. They are calibrated and tested through the application of signal theory, in order to overcome data scarcity over ungauged areas, as well 15 as incomplete discharge time series. The validation has been carried out on a case study basis, through the use of flood reports from various source of information, as well as hydrometric level time series, which represent the actual hydrological quantity monitored by civil protection operators. -

N. 305 Del 30 Luglio 2020

DECRETO DEL DIRIGENTE DELLA P.F. TUTELA DEL TERRITORIO DI PESARO-URBINO ##numero_data## Oggetto: D.Lgs. 152/2006 - R.D. 1775/1933 - L.R. 5/2006. Limitazione dei prelievi dai corsi d’acqua insistenti nel bacino idrografico del Fiume Metauro per il periodo 5 agosto - 30 settembre 2020. VISTO il documento istruttorio e ritenuto, per le motivazioni nello stesso indicate, di adottare il presente decreto. VISTO l’articolo 16 bis della legge regionale 15 ottobre 2001, n. 20 (Norme in materia di organizzazione e di personale della Regione). VISTA la DGR n. 597 del 18/05/2020 ad oggetto “Articolo 28 della Legge Regionale 20/2001. Conferimento incarico dirigenziale della P.F. Tutela del Territorio di Pesaro e Urbino nell’ambito del Servizio tutela, gestione e assetto del territorio della Giunta Regionale”. VISTA la DGR n. 1333/2018 ad oggetto “L.R. n. 20/2001. Parziale modifica delle deliberazioni di organizzazione n. 1536/2016, n. 31/2017 e ss.mm.ii. e delle deliberazioni n. 279/2017 e n. 879/2018 della Giunta regionale”. VISTA la L.R. del 9 giugno 2006 n. 5 “Disciplina delle derivazioni di acqua pubblica e delle occupazioni del demanio idrico. DECRETA 1) Di disporre, a far data dal 5 agosto 2020 e fino al 30 settembre 2020, le seguenti limitazioni dei prelievi dai corsi d’acqua insistenti nel bacino idrografico del fiume Metauro: a) sospensione di tutti i prelievi di acqua pubblica dai corsi d’acqua ubicati nel tratto compreso tra l’invaso del Furlo e la foce del Fiume Metauro (Fiume Candigliano, Fiume Metauro e relativi affluenti); b) riduzione del 50% della portata dei prelievi di acqua pubblica rispetto a quella prevista nei disciplinari di concessione o nelle licenze annuali di attingimento, da tutti i corsi d’acqua presenti a monte del bacino del Furlo (Fiume Candigliano, Fiume Metauro, Fiume Burano, Fiume Biscubio, Fiume Bosso, Torrente Bevano, Torrente Certano e relativi affluenti). -

Tour 1 Ciclotur.EN

[email protected] of San Vincenzo al Furlo al Vincenzo San of Provincia di Pesaro e Urbino e Pesaro di Provincia 3. Acqualagna. Crypt at the Abbey Abbey the at Crypt Acqualagna. 3. www.turismo.pesarourbino.it 2. View of Fossombrone sul Metauro sul Fossombrone of View 2. 1. The River Candigliano at Gola del Furlo del Gola at Candigliano River The 1. Cover: Gola del Furlo with lake lake with Furlo del Gola Cover: 3. Urbino (max. alt. 588 m). m). 588 alt. (max. Urbino An easy uphill stretch leads to the town of town the to leads stretch uphill easy An easier and rather picturesque valley roads. valley picturesque rather and easier number of steep sections alternating with alternating sections steep of number (Cesana and Passo di S.Gregorio) include a include S.Gregorio) di Passo and (Cesana spectacular landscape. The two main climbs main two The landscape. spectacular and Cesane mountain chains through a through chains mountain Cesane and The itinerary winds its way around the Furlo the around way its winds itinerary The 2. Follow road signs for Furlo for signs road Follow Superstrada Grossetto-Fano, Acqualagna Exit • Exit Acqualagna Grossetto-Fano, Superstrada Inland: From Superstrada for Rome. Furlo Exit Exit Furlo Rome. for Superstrada Autostrada A14, Fano Exit • • Exit Fano A14, Autostrada Coast: the From How to reach Furlo: reach to How amateur cyclists amateur Intended for: for: Intended asphalt Type of road: road: of Type Level of difficulty: difficulty: of Level m. 961 961 m. FERMIGNANO Total ascent/descent: Total MONTI DELLE CESANE DELLE MONTI 4 h / 4:30 h 4:30 / h 4 Estimated time: Estimated FOSSOMBRONE km. -

X Tavolo Nazionale Contratti Di Fiume 2015

X TAVOLO NAZIONALE CONTRATTI DI FIUME 2015 “UN TUFFO DOVE L’ACQUA È PIÙ BLÙ …. NIENTE DI PIÙ”: Partecipando con emozione verso il contratto di fiume BBBC (Biscubio, Bosso, Burano e Candigliano – Alto F. Metauro). SESSIONE 2 Tema A : Qualità dei Processi Autori: Enrico Gennari*, Fabrizio Ioiò** Società Italiana di Geologia Ambientale, Sezione Marche *Docente di Progettazione Geologico-Ambientale, Università Carlo Bo di Urbino, ** Geologo, Libero Professionista *[email protected] , **[email protected] ABSTACT Riuscire a costruire un processo partecipativo dal basso, capace di identificare problemi e definire azioni fondamentali per conseguire risultati concreti in territori fluviali periferici come quelli dei Comuni dell’ Area Interna del Basso Appennino Pesarese Anconetano dove ricadono i Fiumi Biscubio, Bosso, Burano e Candigliano, non è stata “impresa semplice”. Intanto il primo problema da risolvere è stato quello di superare la poca conoscenza o disinformazione sui CdF, esaltando i punti di forza e le opportunità che in altre realtà tali strumenti hanno creato. Cercheremo di raccontare come si sia arrivati …. dal nulla.. a far germogliare, crescere e infine a far assumere all’ idea progetto “Contratto di Fiume per il Biscubio, Bosso Burano e Candigliano” il ruolo di azione portante, innovativa e creativa, dell’ Idea guida della Strategia SNAI in questa porzione di territorio Appenninico, in un crescendo di partecipazione emotiva e creativa. Tutto è cominciato dal Concorso fotografico intitolato “E…STATE AL FIUME” …. promosso nel 2014 dall’ Associazione “Davanti alle Quinte”, proseguito con la Conferenza Dibattito di SigeaMarche del Novembre 2914 “CON … TRATTI di FIUME”, per confluire nella STRATEGIA PRELIMINARE SNAI di quel territorio. -

Exploring Inland Marche Region Italy

GB EXPLORING INLAND • MARCHE REGION ITALY THE MARCHE, ITALY IN ONE REGION “If one had to decide which Italian landscape was the most typical, you’d have to choose the Marche… Italy, with its range of landscapes, is a distillation of the world; the Marche is a distillation of Italy.” G. Piovene, Viaggio in Italia, 1957 ANCO 180 km of coastline, stunningly beautiful beaches, 26 cities facing the Adriatic Sea that are ideal sites for a relaxing holiday , the port of Ancona and 9 tourist harbours. 500 piazzas, 1000 important monuments, over a hundred cities boasting great works of art, thousands of churches (200 of which are Romanesque), 183 religious shrines, 34 archeological sites, 72 historic theatres. The largest number of museums and galleries in Italy: 342 out of STELFIDA 239 boroughs. 315 libraries housing over 4 million volumes. Several protected areas: 2 national parks (Monti Sibillini, Gran O Sasso and Monti della Laga), 4 regional parks (Monte Conero, Sasso Simone and Simoncello, Monte San Bartolo, Gola della ASSIANO .S. 77 Rossa and di Frasassi), 5 nature reserves (Abbadia di Fiastra, Gola del Furlo, Montagna di Torricchio, Ripa Bianca and Sentina), more than 100 floristic areas and 15 state woods. ACERAT ETRIOLO ANO M O NE NTANO ANO ENANO COORDINATION Department of Promotion, MON APPE Internationalization, Tourism and Trade Sandro Abelardi NZA TEXT PAL MIA Tourism Service Laura Capozucca VIONE PHOTOGRAPHS BY Tourism Service Archives-Region Marche GRAPHICS Tourism Service Stefano Gregori FREE DISTRIBUTION Edition 2009 MARCHE REGION TOURISM DEPARTMENT ITALY IN ONE REGION THE MARCHE Charcoal pile: an ancient method of preparing charcoal 3 Sheep farming is still an important part of the economy in mountain areas The Marche is a Region of Italy where countryside, covering 69% of the history, culture and countryside have Marche region, blends well with the helped to create a unique and transformations wrought by man over extraordinary world that is worth the course of time through agriculture, discovering.