Scientific Studies on Dry Tortugas National Park: an Annotated Bibliography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park Service Climate Change Action Plan 2012-2014 Letter from the Director

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Climate Change Response Program Climate Change Action Plan 2012–2014 Golden Gate National Recreation Area California, is one of many coastal parks experiencing rising sea level. NPS photo courtesy Will Elder. TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR .................................... 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................ 6 CONTEXT FOR ACTION ............................................ 8 National Directives ............................................. 9 A Servicewide Climate Change Response ...................... 9 1 The Role of the NPS in a Changing Climate ..................10 Flexible Planning ..............................................11 IDENTIFYING NEAR-TERM PRIORITIES ......................... 12 Criteria for Prioritization ......................................13 Eight Emphasis Areas for Action ...............................13 2 Table 1: NPS Commitments to High-Priority Actions ..........................................20 PREPARING FOR NEW CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES ........................................... 28 What to Expect in the Next Few Years ........................29 3 The Road Ahead ...............................................32 CONCLUSION ...................................................34 National Park Service Climate Change Action Plan 2012-2014 Letter from the Director lmost one hundred years ago – long before “the greenhouse effect” or “sea level rise” or even A“climate change” were common concepts – a -

Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School November 2017 Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Megan E. Hepner University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Other Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Hepner, Megan E., "Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary" (2017). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7408 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reef Fish Biodiversity in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary by Megan E. Hepner A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Marine Science with a concentration in Marine Resource Assessment College of Marine Science University of South Florida Major Professor: Frank Muller-Karger, Ph.D. Christopher Stallings, Ph.D. Steve Gittings, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 31st, 2017 Keywords: Species richness, biodiversity, functional diversity, species traits Copyright © 2017, Megan E. Hepner ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am indebted to my major advisor, Dr. Frank Muller-Karger, who provided opportunities for me to strengthen my skills as a researcher on research cruises, dive surveys, and in the laboratory, and as a communicator through oral and presentations at conferences, and for encouraging my participation as a full team member in various meetings of the Marine Biodiversity Observation Network (MBON) and other science meetings. -

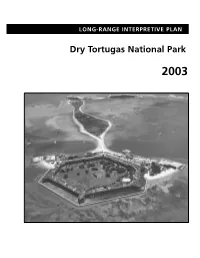

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Dry Tortugas National Park

LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Cover Photograph: Aerial view of Fort Jefferson on Garden Key (fore- ground) and Bush Key (background). COMPREHENSIVE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 LONG-RANGE INTERPRETIVE PLAN Dry Tortugas National Park 2003 Prepared by: Department of Interpretive Planning Harpers Ferry Design Center and the Interpretive Staff of Dry Tortugas National Park and Everglades National Park INTRODUCTION About 70 miles west of Key West, Florida, lies a string of seven islands called the Dry Tortugas. These sand and coral reef islands, or keys, along with 100 square miles of shallow waters and shoals that surround them, make up Dry Tortugas National Park. Here, clear views of water and sky extend to the horizon, broken only by an occasional island. Below and above the horizon line are natural and historical treasures that continue to beckon and amaze those visitors who venture here. Warm, clear, shallow, and well-lit waters around these tropical islands provide ideal conditions for coral reefs. Tiny, primitive animals called polyps live in colonies under these waters and form skeletons from cal- cium carbonate which, over centuries, create coral reefs. These reef ecosystems support a wealth of marine life such as sea anemones, sea fans, lobsters, and many other animal and plant species. Throughout these fragile habitats, colorful fishes swim, feed, court, and thrive. Sea turtles−−once so numerous they inspired Spanish explorer Ponce de León to name these islands “Las Tortugas” in 1513−−still live in these waters. Loggerhead and Green sea turtles crawl onto sand beaches here to lay hundreds of eggs. -

Scarica Il Notiziario S.I.M

NOTIZIARIOPubblicazione semestrale della Società Italiana di Malacologia - c/o Museo di ScienzeS.I.M. Planetarie, via Galcianese 20H - 59100 Prato Anno 31 · n. 2 · luglio-dicembre 2013 Supplemento del Bollettino Malacologico vol. 49 n. 2 Vita societaria a cura di Paolo Crovato e Maurizio Forli Sommario Vita sociale molluschi marini del Mediterraneo. Volume V. A cura di P. Crovato 2 In memoriam Mauro Pizzini (13 luglio 1946 - 4 novembre 2013) 16 Salemi M., 2013 Lumache tropicali- Tropical snail. A cura di M. Forli 4 Verbale della riunione del Consiglio Direttivo tenuta in Montesilvano (PE) il 14 settembre 2013 5 Convocazione dell’Assemblea ordinaria dei soci Eventi S.I.M., Napoli, 7.04.2014 17 San Felice Circeo (RM), 7° Convegno Malacologico 6 Elenco delle pubblicazioni S.I.M. disponibili 17 Prato, Mirabilia, Le Conchiglie - Mostra Mercato 7 Nota del Presidente 18 Cambridge 7-11 settembre 2014, 7° Congresso delle Società Europee di Malacologia 8 Segnalazioni bibliografiche 18 Cefalù-Castelbuono, 16-18 maggio 2014, Presentazione libri e recensioni 2° Congresso Internazionale 18 Mostre e Borse 2014 15 Cecalupo A. & Perugia I., 2013. The Cerithiopsidae (Caenogastropoda: Triphoroidea) of Espiritu Santo - Vanuatu (South Pacific Ocean). Varie A cura di P. Crovato 19 Aggiunte e correzioni all’elenco dei soci 15 Scaperrotta M., Bartolini S. & Bogi C., 2013. Accrescimenti. Stadi di accrescimento dei 20 Quote Sociali 2014 In memoriam Mauro Pizzini (13 luglio 1946 – 4 novembre 2013) Vita sociale Mauro Pizzini ci ha lasciato pochi giorni fa. Martedì 5 novembre è arrivata la notizia che in molti temevamo: un’e-mail di sua figlia Chiara annunciava che Mauro era morto il giorno prima. -

SA Wioresearchcompendium.Pdf

Compiling authors Dr Angus Paterson Prof. Juliet Hermes Dr Tommy Bornman Tracy Klarenbeek Dr Gilbert Siko Rose Palmer Report design: Rose Palmer Contributing authors Prof. Janine Adams Ms Maryke Musson Prof. Isabelle Ansorge Mr Mduduzi Mzimela Dr Björn Backeberg Mr Ashley Naidoo Prof. Paulette Bloomer Dr Larry Oellermann Dr Thomas Bornman Ryan Palmer Dr Hayley Cawthra Dr Angus Paterson Geremy Cliff Dr Brilliant Petja Prof. Rosemary Dorrington Nicole du Plessis Dr Thembinkosi Steven Dlaza Dr Anthony Ribbink Prof. Ken Findlay Prof. Chris Reason Prof. William Froneman Prof. Michael Roberts Dr Enrico Gennari Prof. Mathieu Rouault Dr Issufo Halo Prof. Ursula Scharler Dr. Jean Harris Dr Gilbert Siko Prof. Juliet Hermes Dr Kerry Sink Dr Jenny Huggett Dr Gavin Snow Tracy Klarenbeek Johan Stander Prof. Mandy Lombard Dr Neville Sweijd Neil Malan Prof. Peter Teske Benita Maritz Dr Niall Vine Meaghen McCord Prof. Sophie von der Heydem Tammy Morris SA RESEARCH IN THE WIO ContEnts INDEX of rEsEarCh topiCs ‑ 2 introDuCtion ‑ 3 thE WEstErn inDian oCEan ‑ 4 rEsEarCh ActivitiEs ‑ 6 govErnmEnt DEpartmEnts ‑ 7 Department of Science & Technology (DST) Department of Environmental Affairs (DEA) Department of Agriculture, Forestry & Fisheries (DAFF) sCiEnCE CounCils & rEsEarCh institutions ‑ 13 National Research Foundation (NRF) Council for Geoscience (CGS) Council for Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) Institute for Maritime Technology (IMT) KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board (KZNSB) South African Environmental Observation Network (SAEON) Egagasini node South African -

National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5/31/2012) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form Is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructil'.r!§ ~ ~ tloDpl lj~~r Bulletin How to Complete the Mulliple Property Doc11mentatlon Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the req lBtEa\oJcttti~ll/~ a@i~8CPace, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items X New Submission Amended Submission AUG 1 4 2015 ---- ----- Nat Register of Historie Places A. Name of Multiple Property Listing NatioAal Park Service National Park Service Mission 66 Era Resources B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Pre-Mission 66 era, 1945-1955; Mission 66 program, 1956-1966; Parkscape USA program, 1967-1972, National Park Service, nation-wide C. Form Prepared by name/title Ethan Carr (Historical Landscape Architect); Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Ph.D., (Historian, Architectural); Len Warner (Historian). The Collaborative Inc.'s 2012-2013 team comprised Rodd L. Wheaton (Architectural Historian and Supportive Research), Editor and Contributing Author; John D. Feinberg, Editor and Contributing Author; and Carly M. Piccarello, Editor. organization the Collaborative, inc. date March 2015 street & number ---------------------2080 Pearl Street telephone 303-442-3601 city or town _B_o_ul_d_er___________ __________st_a_te __ C_O _____ zi~p_c_o_d_e_8_0_30_2 __ _ e-mail [email protected] organization National Park Service Intermountain Regional Office date August 2015 street & number 1100 Old Santa Fe Trail telephone 505-988-6847 city or town Santa Fe state NM zip code 87505 e-mail sam [email protected] D. -

Contributions to the Knowledge of the Ovulidae. XVI. the Higher Systematics

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Spixiana, Zeitschrift für Zoologie Jahr/Year: 2007 Band/Volume: 030 Autor(en)/Author(s): Fehse Dirk Artikel/Article: Contributions to the knowledge of the Ovulidae. XVI. The higher systematics. (Mollusca: Gastropoda) 121-125 ©Zoologische Staatssammlung München/Verlag Friedrich Pfeil; download www.pfeil-verlag.de SPIXIANA 30 1 121–125 München, 1. Mai 2007 ISSN 0341–8391 Contributions to the knowledge of the Ovulidae. XVI. The higher systematics. (Mollusca: Gastropoda) Dirk Fehse Fehse, D. (2007): Contributions to the knowledge of the Ovulidae. XVI. The higher systematics. (Mollusca: Gastropoda). – Spixiana 30/1: 121-125 The higher systematics of the family Ovulidae is reorganised on the basis of re- cently published studies of the radulae, shell and animal morphology and the 16S rRNA gene. The family is divided into four subfamilies. Two new subfamilîes are introduced as Prionovolvinae nov. and Aclyvolvinae nov. The apomorphism and the result of the study of the 16S rRNA gene are contro- versally concerning the Pediculariidae. Therefore, the Pediculariidae are excluded as subfamily from the Ovulidae. Dirk Fehse, Nippeser Str. 3, D-12524 Berlin, Germany; e-mail: [email protected] Introduction funiculum. A greater surprise seemed to be the genetically similarity of Ovula ovum (Linneaus, 1758) In conclusion of the recently published studies on and Volva volva (Linneaus, 1758) in fi rst sight but a the shell morphology, radulae, anatomy and 16S closer examination of the shells indicates already rRNA gene (Fehse 2001, 2002, Simone 2004, Schia- that O. -

Assessment of Natural Resource Condition in and Adjacent to Dry

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Assessment of Natural Resource Condition in and Adjacent to the Dry Tortugas National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/DRTO/NRR—2012/558 ON THE COVER Sergeant majors (Abudefduf saxatilis) in Dry Tortugas National Park. Photograph by NOAA/NOS/NCCOS/CCMA Biogeography Branch Assessment of Natural Resource Conditions In and Adjacent to Dry Tortugas National Park Natural Resource Report NPS/DRTO/NRR—2012/558 Christopher F. G. Jeffrey1,2 ,Sarah D. Hile1,2, Christine Addison3, Jerald S. Ault4, Carolyn Currin3, Don Field3, Nicole Fogarty5, Jiangang Luo4, Vanessa McDonough6, Doug Morrison7, Greg Piniak1, Varis Ransibrahmanakul1, Steve G. Smith4, Shay Viehman3 Editor: Christopher F. G. Jeffrey1,2 1National Oceanic and Atmospheric 4University of Miami Administration Rosenstiel School of Marine and National Ocean Service, National Centers Atmospheric Science for Coastal Ocean Science 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway Center for Coastal Monitoring and Miami, FL 33149-1098 Assessment, Biogeography Branch 1305 East West Highway, SSMC4, N/SCI-1 5Nova Southeastern University Silver Spring, MD 20910 Oceanographic Center 8000 N. Ocean Drive 2Consolidated Safety Services, Inc. Dania Beach, Florida 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300 Fairfax, VA 22030 6National Park Service Biscayne National Park 3National Oceanic and Atmospheric 9700 SW 328 Street Administration Homestead, Florida 33033 National Ocean Service, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science 7National Park Service -

Guia Para Observação Das Aves Do Parque Nacional De Brasília

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234145690 Guia para observação das aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília Book · January 2011 CITATIONS READS 0 629 4 authors, including: Mieko Kanegae Fernando Lima Favaro Federal University of Rio de Janeiro Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Bi… 7 PUBLICATIONS 74 CITATIONS 17 PUBLICATIONS 69 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Fernando Lima Favaro on 28 May 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Brasília - 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA Aílton C. de Oliveira Mieko Ferreira Kanegae Marina Faria do Amaral Fernando de Lima Favaro Fotografia de Aves Marcelo Pontes Monteiro Nélio dos Santos Paulo André Lima Borges Brasília, 2011 GUIA PARA OBSERVAÇÃO DAS AVES DO APRESENTAÇÃO PARQUE NACIONAL DE BRASÍLIA É com grande satisfação que apresento o Guia para Observação REPÚblica FEDERATiva DO BRASIL das Aves do Parque Nacional de Brasília, o qual representa um importante instrumento auxiliar para os observadores de aves que frequentam ou que Presidente frequentarão o Parque, para fins de lazer (birdwatching), pesquisas científicas, Dilma Roussef treinamentos ou em atividades de educação ambiental. Este é mais um resultado do trabalho do Centro Nacional de Pesquisa e Vice-Presidente Conservação de Aves Silvestres - CEMAVE, unidade descentralizada do Instituto Michel Temer Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) e vinculada à Diretoria de Conservação da Biodiversidade. O Centro tem como missão Ministério do Meio Ambiente - MMA subsidiar a conservação das aves brasileiras e dos ambientes dos quais elas Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira dependem. -

Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure

Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 Cover picture shows the Flamingo visitor center on Florida Bay. Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections i Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY It is unequivocal that climate is warming, and since the 1950s many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen, and concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased. One of the most robust indicators of a warming climate is rising sea level driven by thermal expansion of ocean water and addition of land-based ice-melt to the ocean, however, sea level rise is not evenly distributed around the globe and the response of a coastline is highly dependent on local natural and human settings. This is particularly evident at the southern end of the Florida peninsula where low elevations and exceedingly flat topography provide an ideal setting for encroachment of the sea. Here, we illustrate projected impacts of sea level rise to infrastructure in Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Parks at four time horizons: 2025, 2050, 2075 and 2100, and under two sea level rise scenarios, a low projection and a high projection. -

FAU Institutional Repository

FAU Institutional Repository http://purl.fcla.edu/fau/fauir This paper was submitted by the faculty of FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute Notice: ©2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. This is the author’s version of a work accepted for publication by Elsevier. Changes resulting from the publishing process, including peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting and other quality control mechanisms, may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. The definitive version has been published at http://www.elsevier.com/locate/csr and may be cited as Lee, Thomas N., Ned Smith (2002) Volume transport variability through the Florida Keys tidal Channels, Continental Shelf Research 22(9):1361–1377 doi:10.1016/S0278‐4343(02)00003‐1 Continental Shelf Research 22 (2002) 1361–1377 Volume transport variability through the Florida Keys tidal channels Thomas N. Leea,*, Ned Smithb a Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, University of Miami, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, Miami, FL 33149, USA b Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution, 5600 US Highway 1, North, Ft. Pierce, FL 34946, USA Received 28 February 2001; received in revised form 13 July 2001; accepted 18 September 2001 Abstract Shipboard measurements of volume transports through the passages of the middle Florida Keys are used together with time series of moored transports, cross-Key sea level slopes and local wind records to investigate the mechanisms controllingtransport variability. Predicted tidal transport amplitudes rangedfrom 76000 m3/s in LongKey Channel to 71500 m3/s in Channel 2. Subtidal transport variations are primarily due to local wind driven cross-Key sea level slopes. -

Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets

Keys TravelerThe Magazine Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets fla-keys.com Decompresssing at Bahia Honda State Park near Big Pine Key in the Lower Florida Keys. ANDY NEWMAN MARIA NEWMAN Keys Traveler 12 The Magazine Editor Andy Newman Managing Editor 8 4 Carol Shaughnessy ROB O’NEAL ROB Copy Editor Buck Banks Writers Julie Botteri We do! Briana Ciraulo Chloe Lykes TIM GROLLIMUND “Keys Traveler” is published by the Monroe County Tourist Development Contents Council, the official visitor marketing agency for the Florida Keys & Key West. 4 Sanctuary Protects Keys Marine Resources Director 8 Outdoor Art Enriches the Florida Keys Harold Wheeler 9 Epic Keys: Kiteboarding and Wakeboarding Director of Sales Stacey Mitchell 10 That Florida Keys Sunset! Florida Keys & Key West 12 Keys National Parks Join Centennial Celebration Visitor Information www.fla-keys.com 14 Florida Bay is a Must-Do Angling Experience www.fla-keys.co.uk 16 Race Over Water During Key Largo Bridge Run www.fla-keys.de www.fla-keys.it 17 What’s in a Name? In Marathon, Plenty! www.fla-keys.ie 18 Visit Indian and Lignumvitae Keys Splash or Relax at Keys Beaches www.fla-keys.fr New Arts District Enlivens Key West ach of the Florida Keys’ regions, from Key Largo Bahia Honda State Park, located in the Lower Keys www.fla-keys.nl www.fla-keys.be Stroll Back in Time at Crane Point to Key West, features sandy beaches for relaxing, between MMs 36 and 37. The beaches of Bahia Honda Toll-Free in the U.S.