• the Seven Mile Bridge (Knight Key Bridge HAER FL-2 Moser Channel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repurposing the East Coast Railway: Florida Keys Extension a Design Study in Sustainable Practices a Terminal Thesis Project by Jacqueline Bayliss

REPURPOSING THE EAST COAST RAILWAY: FLORIDA KEYS EXTENSION A DESIGN STUDY IN SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES A terminal thesis project by Jacqueline Bayliss College of Design Construction and Planning University of Florida Spring 2016 University of Florida Spring 2016 Terminal Thesis Project College of Design Construction & Planning Department of Landscape Architecture A special thanks to Marie Portela Joan Portela Michael Volk Robert Holmes Jen Day Shaw Kay Williams REPURPOSING THE EAST COAST RAILWAY: FLORIDA KEYS EXTENSION A DESIGN STUDY IN SUSTAINABLE PRACTICES A terminal thesis project by Jacqueline Bayliss College of Design Construction and Planning University of Florida Spring 2016 Table of Contents Project Abstract ................................. 6 Introduction ........................................ 7 Problem Statement ............................. 9 History of the East Coast Railway ...... 10 Research Methods .............................. 12 Site Selection ............................... 14 Site Inventory ............................... 16 Site Analysis.................................. 19 Case Study Projects ..................... 26 Limitations ................................... 28 Design Goals and Objectives .................... 29 Design Proposal ............................ 30 Design Conclusions ...................... 40 Appendices ......................................... 43 Works Cited ........................................ 48 Figure 1. The decommissioned East Coast Railroad, shown on the left, runs alongside the Overseas -

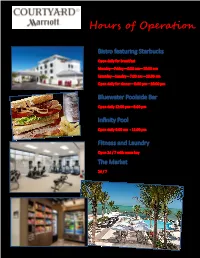

Hours of Operation

Hours of Operation Bistro featuring Starbucks Open daily for breakfast Monday—Friday—6:30 am—10:30 am Saturday—Sunday—7:00 am—10:30 am Open daily for dinner—5:00 pm—10:00 pm Bluewater Poolside Bar Open daily 12:00 pm—8:00 pm Infinity Pool Open daily 6:00 am - 11:00 pm Fitness and Laundry Open 24 / 7 with room key The Market 24 / 7 Airports Marathon Jet Center About 5 minutes away 3.5 Miles Www.marathonjetcenter.com Getting Marathon General Aviation About 6 minutes away Around in the 6 Miles Www.marathonga.com Florida Keys Miami International Airport About 2 hours and 15 minutes away 115 Miles Www.miami-airport.com Fort Lauderdale Airport About 2 hours and 45 minutes away 140 Miles Www.fortlauderdaleinternationalairport.com ******************** Complimentary Shuttle Service Contact the front desk for assistance Taxi and Shuttle Dave’s Island Taxi—305.289.8656 Keys Shuttle—305.289.9997 ******************** Car Rental Enterprise — 305.289.7630 Avis — 305.743.5428 Budget — 305.743.3998 ********************* Marathon Chamber of Commerce 12222 Overseas Highway, Marathon, Florida 33050 305-743-5417 Don’t Miss It in the Florida Keys Key Largo Marathon John Pennekamp State Park Turtle Hospital 102601 Overseas Highway 2396 Overseas Highway 305. 451. 6300 305. 743. 2552 African Queen and Glass Boat Dolphin Research Center U.S. 1 and Mile Marker 100 58901 Overseas Highway 305. 451. 4655 305. 289. 1121 Florida Keys Aquarium Encounters Islamorada 11710 Overseas Highway 305. 407. 3262 Theatre of the Sea 84721 Oversea Highway Sombrero Beach 305.664.2431 Mile Marker 50 305. -

A Good Foundation

A Good Foundation All Aboard: History, Culture, and Innovation on the Florida East Coast Railway Curriculum Connections: Grade Level: Math, Art, Science, Social Studies, Florida History th 4 Grade Objectives: Materials: Students will be introduced to the Florida East Coast Railway and engineering Book: methods for building a bridge foundation under water. They will construct a • Bridges! Amazing Structures cofferdam. to Design, Build and Test by Carol A. Johmann and Standards: Elizabeth J. Rieth Photos: MAFS.4.MD: Measurement and Data • Henry M. Flagler SS.4.G.1: Geography – The World in Spatial Terms • Trains on the Florida East SC.4.P: Physical Science Coast Railway Map of: Corresponding Map Hot Spot: • FEC Railway Showing Extension to Key West Jewfish Creek, FL • FEC Railway Extension to Key West Lesson Procedure Additional Supplies: • Two Medium Sized Bowls Introduction: • Popsicle Sticks • Masking Tape Introduce the theme of the lesson, the bridges of the Overseas Railway. Show • Sand or Dirt the students the pictures of the railroad and the map. • Plastic Wrap • Water Discuss how Henry Flagler was determined to build a railroad connecting the • Turkey Baster or Eye Keys all the way to Key West. Ask the students what they think life may have Droppers been like before the bridges. 1 | All Aboard: History, Culture, and Innovation on the Florida East Coast Railway Discuss the benefits to building a railroad connecting the Florida Keys to mainland Florida (a new way for people to travel, a new way for supplies to get in, etc.) and ask the students what the challenges to building something like this would have been (nothing like this had ever been done before, when the Key West Extension opened it was called the 8th Wonder of the World). -

The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: from Inception To

THE PORTUGUESE EXPEDITIONARY CORPS IN WORLD WAR I: FROM INCEPTION TO COMBAT DESTRUCTION, 1914-1918 Jesse Pyles, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Robert Citino, Committee Member Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Pyles, Jesse, The Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in World War I: From Inception to Destruction, 1914-1918. Master of Arts (History), May 2012, 130 pp., references, 86. The Portuguese Expeditionary Force fought in the trenches of northern France from April 1917 to April 1918. On 9 April 1918 the sledgehammer blow of Operation Georgette fell upon the exhausted Portuguese troops. British accounts of the Portuguese Corps’ participation in combat on the Western Front are terse. Many are dismissive. In fact, Portuguese units experienced heavy combat and successfully held their ground against all attacks. Regarding Georgette, the standard British narrative holds that most of the Portuguese soldiers threw their weapons aside and ran. The account is incontrovertibly false. Most of the Portuguese combat troops held their ground against the German assault. This thesis details the history of the Portuguese Expeditionary Force. Copyright 2012 by Jesse Pyles ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The love of my life, my wife Izabella, encouraged me to pursue graduate education in history. This thesis would not have been possible without her support. Professor Geoffrey Wawro directed my thesis. He provided helpful feedback regarding content and structure. Professor Robert Citino offered equal measures of instruction and encouragement. -

Sea Level Rise Impacts in the Florida Keys

Past and future impacts of sea level rise on terrestrial ecosystems of the Florida Keys Sugarloaf Key, Spring 2006 Mike Ross Florida International University Department of Earth & Environment/Southeast Environmental Research Center Tidal wetlands Fresh water- dependent ecosystems (restricted to the lower Keys, due to its peculiar geology) Tropical hardwood hammocks White-crowned pigeon returning to its Florida Bay nest after feeding in an Upper Keys hammock Elevation: Low --------------------------------------------------------------------------High GW Salinity: l-------Saline-----l-----Brackish--------l----Fresh----l----Brackish----l Species/Site: l—5---5-----5-----13-----15------14---16---29----35---29---24---23---23-l Keys habitat mosaic Within-island habitat mosaic is relatively simple, determined by elevation and salinity. Lower Keys islands have fresher ground water, lower elevations, and a drier climate. Keys ecosystems differ spatially in vulnerability to sea level rise; risk depends greatly on rate of SLR high e.g., Upper Keys hammocks vulnerable e.g., protected shorelines vulnerable e.g., Lower Keys hammocks vulnerable Pine forests & freshwater wetlands Hardwood low hammocks e.g., exposed shorelines vulnerable Mangroves & coastal wetlands 1 ft per 1-2 m per Probability of ecosystem (%) ecosystem loss of Probability century century Rate of sea level rise Pine Forests – doubly vulnerable due to dependence on both fire and fresh groundwater Evidence of environmental change on Sugarloaf Key– pine snags in Ross et al. buttonwood woodland 1994 Recession of Sugarloaf pine forest (toward the interior of the island, toward higher elevations) Projected habitat change with sea level rise on Sugarloaf Key Ross et al. 2009 Hurricane Wilma, October 24th, 2005 Storm Surge in the lower Keys Wilma-related mortality: Sugarloaf Key, 70-100%; Big Pine Key Big Pine Key, 10-90%; Sugarloaf Key - North Sugarloaf Key - South concentrated at elevations < 1m Ross et al. -

Key West Attractions Association Committed to Excellence We Are Truly One the World’S Most Popular Vacation Destinations

Welcome to KEY WEST Key West Attractions Association Committed to Excellence We are truly one the world’s most popular vacation destinations. Key West vacations offer a unique The Key West Attractions Association makes Key West combination of fun and sun, land and sea, as well as vacations great. In a commitment to excellence in family excitement day and night. entertainment, the members of the Key West Attractions Come and take a stroll through historic Old Town and must meet and maintain quality standards of cleanliness, see hundreds of examples of 19th century architecture. safety, truth in advertising, hospitality and proper complaint Sail just seven miles offshore and experience North resolution. What’s your attraction to Key West? The island America’s only living coral reef. Tour the homes of lifestyle, laid-back and relaxed? Ocean views, swaying Hemingway and Harry Truman. Enjoy deep-sea and flats palms, the flavors of the sea? The excitement of watersports sports fishing, boating, diving, snorkeling and jet skiing. by day and wild life by night? The step back in time to a Join the sunset party on a pier or the water. Visit some of swashbuckling era of pirates and treasure-laden shipwrecks? the most unique museums in the U.S. And, experience Or is it the local color? The oranges and purples of our famous our heritage in art galleries, shops, hotels and restaurants sunsets, the green of banana leaves, palm designed to suit every style and taste. fronds and sea turtles, the blue According to legend, once Key West sand gets in and turquoise of the water your shoes, you’ll return again and again. -

Florida Keys Destination Guide

s y e .k a l f . The Florida Keys & Key West: 0 80 . come as you are 1 m o .c s y ke - la f fla-keys.com 1.800.fla.keys THE FLORIDA KEYS Most people know the Florida Keys and Key West as a great getaway. One of the most unique places on earth. Calm. Serene. Laid back. Just the right setting to recharge your batteries and rejuvenate your spirits. But a getaway to the Florida Keys and Key West is much more than peace and quiet. And not just because of the legendary fishing and the world’s most spectacular dive sites. The Keys mean history. Art. Theater. Museums. Shopping. Fine dining. Entertainment. And much more. All told, 120 miles of perfect balance between natural beauty and extra-ordinary excitement. Between relaxation and activities. Between the quaint and the classic. And you’ll find our accommodations just as diverse as our pleasures. From some of the best camping spots in the country to luxurious hotels. From charming bed-and-breakfasts to rustic, family-owned lodgings. In other words, we’ve got something for everyone. In the next few pages you’ll get to know what your Florida Keys vacation can and will be like. What you’d expect. And what will surprise you. Our fame and our secrets. We figured we owed it to you. After all, we wouldn’t want you to get here and wish you had booked just a few more days. For the latest on health & safety protocols in The Florida Keys, please visit our website. -

Executive Summary

Coco Palms 21585 Old State Road 4A Cudjoe Key, Florida TRAFFIC STUDY prepared for: Smith Hawks KBP CONSULTING, INC. January 2018 Revised July 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................................... 1 INVENTORY ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Existing Land Use and Access ......................................................................................................... 3 Proposed Land Use and Access ........................................................................................................ 3 EXISTING CONDITIONS ........................................................................................................................... 4 Existing Roadway Network .............................................................................................................. 4 Existing Traffic Conditions .............................................................................................................. 4 TRIP GENERATION ................................................................................................................................... 5 TRIP DISTRIBUTION ................................................................................................................................. 6 TRAFFIC IMPACT ANALYSES ............................................................................................................... -

Appendix C - Monroe County

2016 Supplemental Summary Statewide Regional Evacuation Study APPENDIX C - MONROE COUNTY This document contains summaries (updated in 2016) of the following chapters of the 2010 Volume 1-11 Technical Data Report: Chapter 1: Regional Demographics Chapter 2: Regional Hazards Analysis Chapter 4: Regional Vulnerability and Population Analysis Funding provided by the Florida Work completed by the Division of Emergency Management South Florida Regional Council STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY This page intentionally left blank. STATEWIDE REGIONAL EVACUATION STUDY – SOUTH FLORIDA APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX C – MONROE COUNTY Page A. Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 B. Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 C. Demographic Trends ...................................................................................... 4 D. Census Maps .................................................................................................. 9 E. Hazard Maps .................................................................................................15 F. Critical Facilities Vulnerability Analysis .............................................................23 List of Tables Table 1 Small Area Data ............................................................................................. 1 Table 2 Health Care Facilities Vulnerability -

NCEF a Connector of Resources Within Collier County During COVID-19

A8 NEWS WEEK OF MAY 7-13, 2020 www.FloridaWeekly.com NAPLES FLORIDA WEEKLY Owner of cinema group building at Coastland Center files for bankruptcy FLORIDA WEEKLY Certain news outlets including the Wall Street Journal reported this week that the owner of CMX Cinemas has filed for bankruptcy protection. As pre- viously reported in Florida Weekly, a state-of-the-art CMX Cinébistro movie theater is currently being built on the footprint of the former Sears store at Coastland Center mall in Naples. According to an April 27 article about the bankruptcy filing from The Real Deal, which reports on real estate news, Miami-based Cinemex Holdings USA filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in Miami. The company is owned by Mexico-based Grupo Cinemex SA de CV, which controls CMX Cinemas with 41 locations in the Midwest, Northeast and the South, Real Deal reported. CMX Cinemas had planned to open new locations at Wrigleyville in Chi- cago; American Dream Mall in East Rutherford, New Jersey; and Coastland Center in Naples this year, according to its website. The Wall Street Journal reported that the owner of CMX Cinemas filed for bankruptcy protection saying it needs breathing room from movie studios and landlords because of the economic cri- ERIC STRACHAN / FLORIDA WEEKLY sis triggered by the coronavirus pan- Workmen were on the jobsite Tuesday where the CMX Cinébistro movie theater is under construction at Coastland Center mall. demic. In a statement, CMX Cin- thet country, the Miami Herald As reported by Real Deal’s Keith er, Scotia Bank, HSBC Mexico, and SAB- emas said it had experienced a reported. -

Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure

Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 Cover picture shows the Flamingo visitor center on Florida Bay. Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 South Florida Natural Resources Center Everglades National Park Homestead, Florida National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections i Sea Level Rise and Inundation Projections for Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Park Infrastructure November 21, 2016 Technical Report SFNRC 2016:11-21 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY It is unequivocal that climate is warming, and since the 1950s many of the observed changes are unprecedented over decades to millennia. The atmosphere and ocean have warmed, snow and ice have diminished, sea level has risen, and concentrations of greenhouse gases have increased. One of the most robust indicators of a warming climate is rising sea level driven by thermal expansion of ocean water and addition of land-based ice-melt to the ocean, however, sea level rise is not evenly distributed around the globe and the response of a coastline is highly dependent on local natural and human settings. This is particularly evident at the southern end of the Florida peninsula where low elevations and exceedingly flat topography provide an ideal setting for encroachment of the sea. Here, we illustrate projected impacts of sea level rise to infrastructure in Everglades, Biscayne and Dry Tortugas National Parks at four time horizons: 2025, 2050, 2075 and 2100, and under two sea level rise scenarios, a low projection and a high projection. -

Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets

Keys TravelerThe Magazine Keys Sanctuary 25 Years of Marine Preservation National Parks Turn 100 Offbeat Keys Names Florida Keys Sunsets fla-keys.com Decompresssing at Bahia Honda State Park near Big Pine Key in the Lower Florida Keys. ANDY NEWMAN MARIA NEWMAN Keys Traveler 12 The Magazine Editor Andy Newman Managing Editor 8 4 Carol Shaughnessy ROB O’NEAL ROB Copy Editor Buck Banks Writers Julie Botteri We do! Briana Ciraulo Chloe Lykes TIM GROLLIMUND “Keys Traveler” is published by the Monroe County Tourist Development Contents Council, the official visitor marketing agency for the Florida Keys & Key West. 4 Sanctuary Protects Keys Marine Resources Director 8 Outdoor Art Enriches the Florida Keys Harold Wheeler 9 Epic Keys: Kiteboarding and Wakeboarding Director of Sales Stacey Mitchell 10 That Florida Keys Sunset! Florida Keys & Key West 12 Keys National Parks Join Centennial Celebration Visitor Information www.fla-keys.com 14 Florida Bay is a Must-Do Angling Experience www.fla-keys.co.uk 16 Race Over Water During Key Largo Bridge Run www.fla-keys.de www.fla-keys.it 17 What’s in a Name? In Marathon, Plenty! www.fla-keys.ie 18 Visit Indian and Lignumvitae Keys Splash or Relax at Keys Beaches www.fla-keys.fr New Arts District Enlivens Key West ach of the Florida Keys’ regions, from Key Largo Bahia Honda State Park, located in the Lower Keys www.fla-keys.nl www.fla-keys.be Stroll Back in Time at Crane Point to Key West, features sandy beaches for relaxing, between MMs 36 and 37. The beaches of Bahia Honda Toll-Free in the U.S.