Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Segantin Kg Tcc Arafcl.Pdf (202.1Kb)

UNESP UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” Faculdade de Ciências e Letras Campus de Araraquara – SP KARINA GOMES SEGANTIN A TRADUÇÃO DO CONTO “LANGE SCHATTEN” DE MARIE LUISE KASCHNITZ Araraquara – SP 2010 UNESP UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL PAULISTA “JÚLIO DE MESQUITA FILHO” Faculdade de Ciências e Letras Campus de Araraquara – SP KARINA GOMES SEGANTIN A TRADUÇÃO DO CONTO “LANGE SCHATTEN” DE MARIE LUISE KASCHNITZ Monografia apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras – Unesp/Araraquara como requisito para obtenção do título de Bacharel em Letras, realizada sob orientação da Profª Drª Maria Cristina Reckziegel Guedes Evangelista. Araraquara – SP 2010 Segantin, Karina Gomes A tradução do conto “Lange Schatten” de Marie Luise Kaschnitz / Karina Gomes Segantin. – 2010 31 f. ; 30 cm Trabalho de conclusão de curso (Graduação em Letras) – Universidade Estadual Paulista, Faculdade de Ciências e Letras, Campus de Araraquara Orientador: Maria Cristina Reckziegel Guedes Evangelista 1. Conto alemão – Tradução para o português. 2. Kaschnitz, Marie Luise. I. Título. KARINA GOMES SEGANTIN Monografia apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras – Unesp/Araraquara como requisito para obtenção do título de Bacharel em Letras, realizada sob orientação da Profª Drª Maria Cristina Reckziegel Guedes Evangelista. Banca Examinadora: _______________________________________ Profª Drª Maria Cristina Reckziegel Guedes Evangelista Orientadora – UNESP - Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Araraquara _______________________________________ Profª Drª Karin Volobuef UNESP – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Araraquara _______________________________________ Profª Drª Wilma Patrícia M. Dinardo Maas UNESP – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Araraquara Araraquara, ___ de ____________ de 2010 AGRADECIMENTOS A minha família e ao Felipe, meu namorado, pelo amor e pelo apoio de sempre. -

SWR2 Essay Extra Die Große Kulturmaschine Funk 60 Jahre Radio-Essay

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT ESSAYS FEATURES KOMMENTARE VORTRÄGE SWR2 Essay extra Die Große Kulturmaschine Funk 60 Jahre Radio-Essay Teil 1 „Die große Kulturmaschine Funk“. 60 Jahre Radio-Essay Von Stephan Krass Teil 2 Ein Radiohörer mit runden Ohren, der Arno Schmidt und Wolfgang Koeppen hört. Von Sibylle Lewitscharoff Sendung: Montag, 14.09. 2015 Redaktion: Stephan Krass Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers Service: SWR2 Essay können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de oder als Podcast nachhören: http://www1.swr.de/podcast/xml/swr2/essay.xml Mitschnitte aller Sendungen der Redaktion SWR2 Essay sind auf CD erhältlich beim SWR Mitschnittdienst in Baden-Baden zum Preis von 12,50 Euro. Bestellungen über Telefon: 07221/929-26030 Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de 1 Teil 1 Die große Kulturmaschine Funk – 60 Jahre Radio-Essay Von Stephan Krass Am 12. Juli 1955 – vor 60 Jahren - ging beim SDR in Stuttgart ein Programm auf Sendung, das auf den Namen Radio-Essay getauft wurde. Aus diesem Anlass veranstaltete SWR2 am 25. Juni 2015 im Literaturhaus Stuttgart ein Symposion, auf dem der runde Geburtstag gefeiert wurde. SWR2 extra sendet die Vorträge dieser Jubiläumsveranstaltung bis kommenden Freitag jeden Abend um 22:03 Uhr. -

Readingsample

insel taschenbuch 3275 Herrlich wie am ersten Tag 125 Gedichte und ihre Interpretationen Bearbeitet von Johann Wolfgang Goethe, Marcel Reich-Ranicki 1. Auflage 2008. Taschenbuch. 566 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 458 34975 4 Format (B x L): 10,6 x 17,5 cm Gewicht: 280 g schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Insel Verlag Leseprobe Goethe, Johann Wolfgang »Herrlich wie am ersten Tag« 125 Gedichte und ihre Interpretationen Ausgewählt von Marcel Reich-Ranicki © Insel Verlag insel taschenbuch 3275 978-3-458-34975-4 Goethes Lyrik ist immer noch und heute erst recht: eine Fund- grube, in der sich mehr verbirgt, als wir uns vorstellen können. Aus seinem riesigen und einzigartigen Werk werden 125 Ge- dichte vorgelegt und von ihren Kennern kommentiert, berühmte ebenso wie wenig bekannte, wenn nicht gar vergessene. Mit ihren persönlichen Deutungen zeigen uns die Interpreten, wie man diese Gedichte begreifen kann, nicht, wie man sie begreifen muß – und regen uns damit an, sie aufmerksam zu lesen und auf unsere Weise zu verstehen. Es äußern sich Lyriker wie Hilde Domin, Karl Krolow, Elisabeth Borchers und Ernst Jandl, Günter Kunert und Ulla Hahn, Schriftsteller wie Wolfgang Koeppen, Golo Mann und Siegfried Lenz, Literaturhistoriker wie Benno von Wiese, Peter Demetz und Peter Wapnewski, Kritiker wie Hilde Spiel, Günter Blöcker und Joachim Kaiser sowie Siegfried Unseld. -

Auf Der Suche Nach Dem Verlorenen Ich Wolfgang Koeppens Spätwerk

Auf der Suche nach dem verlorenen Ich Wolfgang Koeppens Spätwerk Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE (Dr. phil.) von der Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Karlsruhe angenommene DISSERTATION von Matthias Kußmann aus Karlsruhe Dekan: Prof. Dr. Bernd Thum 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Hansgeorg Schmidt-Bergmann 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jan Knopf Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 8. November 2000 Inhalt 1 Einleitung 1 2 Übergang − Der Weg zum Spätwerk 17 3 "Wir sind von Anbeginn verurteilt" − Jugend (1976) 39 3.1 Zeitgeschichte, Gesellschaft und Architektur als Kulissen 41 3.2 Anfang und Ende: Mutterbindung, Verurteilung, Schuld 46 3.2.1 Der Anfang von Jugend 46 3.2.2 Der letzte Abschnitt von Jugend 55 3.3 Zur Chronologie der Lebensgeschichte 65 3.3.1 Genesis und Apokalypsis als formaler Rahmen 65 3.3.2 Stationen des Scheiterns 67 3.4 Der Ich-Erzähler als Fremder 88 4 "... ein düsteres Selbstgespräch" − Erzählungen, Prosa, Fragmente 94 4.1 "... meine Landschaft": Ein Kaffeehaus (1965) 96 4.2 "Keine Engel. Keine Teufel. Nichts": An mich selbst (1967) 104 4.3 Homo homini lupus: Angst (1974) 112 4.4 "Eine neue Auferstehung des alten Odysseus": Morgenrot (1976) 127 4.5 Korrektur der eigenen Biographie: Ein Anfang ein Ende (1978) 144 4.6 "... und ich schrieb eine Geschichte, die Frieda hieß": 152 Taugte Frieda wirklich nichts? (1982) 5 Eine "Bruderschaft" errichten − Literarische Essays 159 6 Idylle und Melancholie − Die späte Reiseprosa 170 6.1 Rückkehr ins Märchenland: Es war einmal in Masuren -

Deutsche Gedichte Und Ihre Interpretationen

1000 Deutsche Gedichte und ihre Interpretationen Herausgegeben von Marcel Reich-Ranicki Dritter Band Von Friedrich von Schiller bis Joseph von Eichendorff Insel Verlag Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz: An die Sonne (Gert Ueding) Willkommen (Peter von Matt) Wo bist du itzt? (Ludwig Harig) Friedrich von Schiller: Das Mädchen aus der Fremde (Gert Ueding) Das Mädchen aus Orleans (Benno von Wiese) Der Pilgrim (Helmut Koopmann) Die Teilung der Erde (Peter von Matt) Die Worte des Wahns (Walter Hinderer) Dithyrambe (Wolfgang Koeppen) Nänie (Joachim C. Fest) Punschlied (Peter von Matt) Spruch des Confucius (Eckhard Heftrich) Johann Peter Hebel: Wie heißt des Kaisers Töchterlein? (Peter von Matt) Friedrich Hölderlin: Abbitte (Gerhard Schulz) An Zimmern (Cyrus Atabay) Das Angenehme dieser Welt hab' ich genossen (Hans Christoph Buch) Der Frühling (Walter Jens) Der Spaziergang (Renate Schostack) Der Tod für's Vaterland (Wolf Biermann) Der Winkel von Hardt (Peter Härtling) Ganymed (Samuel Bäcbli) Hälfte des Lebens (Ernst Jandl) Lebenslauf (Elisabeth Borchers) Natur und Kunst (Dieter Borchmeyer) Sokrates und Alkibiades (Walter Hinderer) Wenn aus dem Himmel... (Friedrich Wilhelm Korff) Wie Meeresküsten... (Ludwig Harig) An die Parzen (Marcel Reich-Ranicki) Novalis: Ich sehe dich in tausend Bildern (Iring Fetscher) Wenn nicht mehr Zahlen und Figuren (Hans Maier) Wilhelm H. Wackenroder: Siehe wie ich trostlos weine (Hans Rudolf Vaget) Heinrich von Kleist: An den König von Preußen (Günter de Bruyn) An die Königin Luise von Preußen (Hermann Kurzke) Katharina -

Ernst Jandl Und Die Internationale Avantgarde

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts “EIN BEITRAG ZUR MODERNEN WELTDICHTUNG“ ERNST JANDL UND DIE INTERNATIONALE AVANTGARDE A Dissertation in German by Katja Stuckatz © 2014 Katja Stuckatz Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 ii The dissertation of Katja Stuckatz was reviewed and approved* by the following: Martina Kolb Assistant Professor of German and Comparative Literature Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Thomas O. Beebee Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Comparative Literature and German Stefan Matuschek Professor of German and Comparative Literature Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena (Germany) Special Signatory Daniel L. Purdy Professor of German Adrian J. Wanner Professor of Russian and Comparative Literature B. Richard Page Associate Professor of German and Linguistics Head of the Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT (ENGLISH) “A Contribution to Modern World Poetry” Ernst Jandl and the International Avant-Garde My dissertation uses close textual analysis and unpublished archival material to explore the poetic internationalism of the Austrian experimental poet Ernst Jandl (1925-2000). When Jandl died thirteen years ago, four of the world’s biggest newspapers (The Independent, The Times, The Daily Telegraph, and The New York Times) published obituaries to honor a poet whose œuvre marks one of the most influential contributions to German speaking poetry since World War II. This fact testifies not only to the international significance of Jandl’s lyric œuvre, but also to the relations of mutual aesthetic influence between the German and English speaking worlds after the catastrophe of World War II. -

Authority and Obedience in Bernhard Schlink's Der Vorleser and Die

Authority and Obedience in Bernhard Schlink’s Der Vorleser and Die Heimkehr by Margit Assmann Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts University of Tasmania September 2010 i Statements This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma at the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Margit Assmann Date: 21 September 2010 ii Abstract In presenting the crimes of SS-guards through the medium of an illiterate woman, Schlink’s novel Der Vorleser (1995) attracted a mainly stern critical response. The much-criticised one-sided portrayal of destructive obedience seems to be addressed by his next novel Die Heimkehr (2006), where submission to malevolent authority is transferred to an intellectual platform set in America in the years following World War II. Although Schlink maintains he did not intend Die Heimkehr as a sequel to Der Vorleser, there are several thematic aspects linking the two novels. Both have a male German narrator, who was born around the end of World War II and has close links with a former Nazi collaborator. At the centre of both novels is Schlink’s portrayal of the nature of obedience to authority, uncovering the reality of man’s divided nature that consists in both good and evil. -

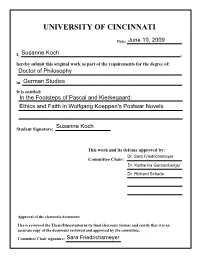

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: June 10, 2009 I, Susanne Koch , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in German Studies It is entitled: In the Footsteps of Pascal and Kierkegaard: Ethics and Faith in Wolfgang Koeppen's Postwar Novels Susanne Koch Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Dr. Sara Friedrichsmeyer Committee Chair: Dr. Katharina Gerstenberger Dr. Richard Schade Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Sara Friedrichsmeyer In the Footsteps of Pascal and Kierkegaard: Ethics and Faith in Wolfgang Koeppen’s Postwar Novels A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies at the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Doctorate of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of German Studies of the College of Arts and Sciences 2009 by Susanne Koch Master of Arts, University of Cincinnati, 2003 Bachelor of Arts, University of Cincinnati, 2001 Committee Chair: Professor Sara Friedrichsmeyer Abstract In focus of this dissertation are the philosophical and Christian dimensions of Wolfgang Koeppen’s postwar novels, Tauben im Gras (1951), Das Treibhaus (1953), and Der Tod in Rom (1954). The author claimed to be neither a philosophical nor a religious writer. Nevertheless, Koeppen raised in his postwar novels fundamental -

Book Factsheet Alfred Andersch Flight to Afar

Book factsheet Alfred Andersch General Fiction, Compulsory Reading Flight to Afar 192 pages 11.3 × 18 cm October 2006 Published by Diogenes as Sansibar oder der letzte Grund Original title: Sansibar oder der letzte Grund World rights are handled by Diogenes Rights currently sold: Chinese/CN (FLTRP) Movie adaptations 1993: Tochter Cast: Rudin Denise, Förnbacher Helmut 1988: Die Kirschen der Freiheit Director: Stephan Reinhardt 1987: Sansibar oder der letzte Grund Director: Bernhard Wicki Screenplay: Karin Hagen Cast: Peter Kremer, Cornelia Schmaus, Gisela Stein 1985: Vater eines Mörders Director: Carl-Heinz Caspari 1977: Winterspelt 1944 Director: Eberhard Fechner Cast: Ulrich von Dobschütz, Katharina Thalbach, Hans-Christian Blech 1965: Haakons Hosentaschen Director: Martin Bosboom Cast: Filmessay/Dokumentation (HR) von Alfred Andersch, aus der das Buch »Hohe Breitengrade« entstand. 1962: La rossa Director: Helmut Käutner Cast: Ruth Leuwerik, Rossanzo Brazzi, Gert Fröbe 1961: Sansibar oder der letzte Grund A boy dreaming of Huckleberry Finn, a mortally ill Pastor, a Director: Rainer Wolffhardt Cast: Robert Graf, Beatrice Schweizer, Paul disillusioned Communist, a young Jewish girl running for her life - Dahlke meet in a half-derelict Baltic fishing village and are drawn into a daring plan of escape from Nazi Germany. At the center of their plan is a small statue in the Pastor's church, a statue which is to be Praise confiscated because it is politically dangerous, a statue so beautiful and powerful that it welds together the strangely assorted band of Flight to Afar refugees. »A wonderful book.« – Wolfgang Koeppen This unusual novel - unusual in both form and content - is a masterpiece of condensed dramatic writing. -

Die Gesellschaft in Der Kritik Der Deutschen Literatur Stuttgart

HANS WAGENER, ED. of thousands of copies in the Germany of Zeitkritische Romane des 20. the 1920ies), we see how "tame," imprac tical, and hopelessly "weltfremd" those Jahrhunderts: Die Gesellschaft in der German novelists were. Many seem to have Kritik der deutschen Literatur had no contact with the masses what Stuttgart: Reclam, 1975. Pp. 392. ever; they wrote their books without giving a thought to the intellectual (or even stylistic) level of the people who—they In his preface, Wagener says that, in thought—should be influenced by their the case of most authors, it would not be works. Frank, Fallada, and Anna Seghers wise to differentiate between "Zeitkritik" could—potentially—be understood by the on the one hand and "Gesellschaftskritik" masses; all others had little chance of on the other. The epoch covered in reaching a large readership. Kästner began Wagener's book is subdivided into the fol to produce popular literature only when it lowing periods: 1. The Society of the was too late. "Kaiserreich," 2. The Weimar Republic, 3. The Third Reich, 4. The Immediate Things changed after 1945. There is no Postwar Period, 5. The Affluent Society doubt about the popularity and integrity since about 1965. Sixteen authors are of Frisch, Walser, Böll, and Grass; they considered: Heinrich Mann, Alfred Dublin, are, in every respect, more sensitive and Leonhard Frank, Hermann Broch, Hans much more influential than their prewar Fallada, Erich Kästner, Hermann Kesten, colleagues; no wonder, they seem to survive Anna Seghers, Ernst Glaeser, Stefan the concerted attacks launched against Andres, Wolfgang Koeppen, Max Frisch, them from the political right. -

Rundfunkarbeiten Brita Steinwendtners

Rundfunkarbeiten Brita Steinwendtners Die im Folgenden angeführte Liste wurde im Zuge der Digitalisierung der Tondokumente von Rundfunkarbeiten Brita Steinwendtners auf MP3-Format durch die Österreichische Mediathek als Kooperationsprojekt mit dem LAS von der Österreichischen Mediathek erstellt und für die Benutzung im LAS geringfügig adaptiert. Inhalt: Unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen, Radiosendung-Sendematerialien, Radiosendung-Mitschnitte von Brita Steinwendtner Die Audio-Dateien wurden alle auf MP3 migriert. 243 Audio-Kompaktkassetten: Signaturen 6-44501 bis 6-44665, 6-44690 bis 6-44698, 6-52599 bis 6-52646, 6-56585 bis 6-56589, 6-56735 bis 6-56737, 6-57769 bis 6-57781 12 CDs: Signaturen 8-38214, 8-49099 bis 8-49108, 8-49222 776 Tonbänder: Signaturen 9-22602 bis 9-23231, 9-23752, 9-26949 bis 9-27020, 9-27584 bis 9-27656 137 Tonbänder klein: Signaturen 10-19219 bis 10-19329, 10-19438, 10-22209 bis 10-22225, 10-24740 bis 10-24747 112 DAT-Kassetten: Signaturen 11-02504 bis 11-02572, 11-02940 bis 11-02978, 11-03906 bis 11-03919 8 Audiodateien: Signaturen e12-01703 bis e12-01710 3 Filme (mpg-Dateien) 1 Signatur 6 - Audio-Kompaktkassetten Hauptsachtitel 30. April 1938; Kassette 1 Titelzusatz Der 50. Tag nach dem Einmarsch Verfasser/Beteiligte Kos, Wolfgang [Gestaltung]; Wischenbart, Rüdiger [Gestaltung]; Botz, Gerhard [Sprecher] Ausführ.Körp./Veranstalter ORF Gesamtwerk / Reihe Diagonal - Radio für Zeitgenossen Gesamtwerk / Reihe „Ein Tag unter dem Radio-Mikroskop“ gesendet am 30. April 1988 Laufzeit Stück 87 min 18 s Datum (jjjj.mm.dd) 1988.04.30 [Sendedatum] Angaben zu Träger/MEX Sign.: 6-00248_a * Techn.Bes.: Kompaktkassette Angaben zu Träger/MEX Sign.: 6-00248_b * Techn.Bes.: Kompaktkassette Hauptsachtitel 30. -

Michael Hofmann/1

Michael Hofmann/1 MICHAEL HOFMANN Department of English University of Florida Gainesville, Florida 32611 352-392-6650 Education Cambridge University, BA, 1979 Cambridge University, MA, 1984 Teaching Visiting Lecturer, University of Florida, 1990 Distinguished Visiting Lecturer, University of Florida, 1994- Visiting Associate Professor, University of Michigan, 1994 Craig-Kade Visiting Writer, German Department, Rutgers University, New Jersey, 2003 Visiting Associate Professor, Barnard College, Columbia University, New York, 2005 Visiting Associate Professor, The New School University, New York, 2005 Professor and Co-Director of Creative Writing, University of Florida, 2013- Term Professor, University of Florida, 2017- Books Poetry Introduction 5 (Faber & Faber, 1982) [one of seven poets] Nights in the Iron Hotel (Faber & Faber, 1983) Acrimony (Faber & Faber, 1986) K.S. in Lakeland: New and Selected Poems (Hopewell, New Jersey: Ecco, 1990) Corona, Corona (Faber & Faber, 1993) Penguin Modern Poets 13 (Penguin, 1998) [one of a trio with Robin Robertson and Michael Longley] Approximately Nowhere (Faber & Faber, 1999) Behind the Lines: Pieces on Writing and Pictures (Faber & Faber, 2001) Arturo Di Stefano (London, Merrell, 2001) [with John Berger and Christopher Lloyd] Selected Poems (Faber & Faber, 2008; FSG, 2009) Where Have You Been: Selected Essays (FSG, 2014, Faber 2015) One Lark, One Horse (Faber, 2018) foreign editions Nachten in het ijzeren hotel [Nights in the Iron Hotel] translated by Adrienne Michael Hofmann/2 van Heteren and Remco