Rails to Carry Copper a History of the Magma Arizona

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Arizona History Index, M

Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 NOTE: the index includes two citation formats. The format for Volumes 1-5 is: volume (issue): page number(s) The format for Volumes 6 -54 is: volume: page number(s) M McAdams, Cliff, book by, reviewed 26:242 McAdoo, Ellen W. 43:225 McAdoo, W. C. 18:194 McAdoo, William 36:52; 39:225; 43:225 McAhren, Ben 19:353 McAlister, M. J. 26:430 McAllester, David E., book coedited by, reviewed 20:144-46 McAllester, David P., book coedited by, reviewed 45:120 McAllister, James P. 49:4-6 McAllister, R. Burnell 43:51 McAllister, R. S. 43:47 McAllister, S. W. 8:171 n. 2 McAlpine, Tom 10:190 McAndrew, John “Boots”, photo of 36:288 McAnich, Fred, book reviewed by 49:74-75 books reviewed by 43:95-97 1 Index to the Journal of Arizona History, M Arizona Historical Society, [email protected] 480-387-5355 McArtan, Neill, develops Pastime Park 31:20-22 death of 31:36-37 photo of 31:21 McArthur, Arthur 10:20 McArthur, Charles H. 21:171-72, 178; 33:277 photos 21:177, 180 McArthur, Douglas 38:278 McArthur, Lorraine (daughter), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Lorraine (mother), photo of 34:428 McArthur, Louise, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Perry 43:349 McArthur, Warren, photo of 34:428 McArthur, Warren, Jr. 33:276 article by and about 21:171-88 photos 21:174-75, 177, 180, 187 McAuley, (Mother Superior) Mary Catherine 39:264, 265, 285 McAuley, Skeet, book by, reviewed 31:438 McAuliffe, Helen W. -

Arizona State Rail Plan March 2011

Arizona State Rail Plan March 2011 Arizona Department of Transportation This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements The State Rail Plan was made possible by the cooperative efforts of the following individuals and organizations who contributed significantly to the successful completion of the project: Rail Technical Advisory Team Cathy Norris, BNSF Railway Chris Watson, Arizona Corporation Commission Bonnie Allin, Tucson Airport Authority Reuben Teran, Arizona Game and Fish Department Zoe Richmond, Union Pacific Railroad David Jacobs, Arizona State Historic Preservation Office Jane Morris, City of Phoenix – Sky Harbor Airport Gordon Taylor, Arizona State Land Department Patrick Loftus, TTX Company Cathy Norris, BNSF Railway Angela Mogel, Bureau of Land Management ADOT Project Team Jack Tomasik, Central Arizona Association of Governments Sara Allred, Project Manager Paul Johnson, City of Yuma Kristen Keener Busby, Sustainability Program Manager Jermaine Hannon, Federal Highway Administration John Halikowski, Director Katai Nakosha, Governor’s Office John McGee, Executive Director for Planning and Policy James Chessum, Greater Yuma Port Authority Mike Normand, Director of Transit Programs Kevin Wallace, Maricopa Association of Governments Shannon Scutari, Esq. Director, Rail & Sustainability Marc Pearsall, Maricopa Association of Governments Services Gabe Thum, Pima Association of Governments Jennifer Toth, Director, Multi-Modal Planning Division Robert Bohannan, RH Bohannan & Associates Robert Travis, State Railroad Liaison Jay -

PC*MILER Geocode Files Reference Guide | Page 1 File Usage Restrictions All Geocode Files Are Copyrighted Works of ALK Technologies, Inc

Reference Guide | Beta v10.3.0 | Revision 1 . 0 Copyrights You may print one (1) copy of this document for your personal use. Otherwise, no part of this document may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, magnetic, optical, or otherwise, without prior written permission from ALK Technologies, Inc. Copyright © 1986-2017 ALK Technologies, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ALK Data © 2017 – All Rights Reserved. ALK Technologies, Inc. reserves the right to make changes or improvements to its programs and documentation materials at any time and without prior notice. PC*MILER®, CoPilot® Truck™, ALK®, RouteSync®, and TripDirect® are registered trademarks of ALK Technologies, Inc. Microsoft and Windows are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and other countries. IBM is a registered trademark of International Business Machines Corporation. Xceed Toolkit and AvalonDock Libraries Copyright © 1994-2016 Xceed Software Inc., all rights reserved. The Software is protected by Canadian and United States copyright laws, international treaties and other applicable national or international laws. Satellite Imagery © DigitalGlobe, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Weather data provided by Environment Canada (EC), U.S. National Weather Service (NWS), U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and AerisWeather. © Copyright 2017. All Rights Reserved. Traffic information provided by INRIX © 2017. All rights reserved by INRIX, Inc. Standard Point Location Codes (SPLC) data used in PC*MILER products is owned, maintained and copyrighted by the National Motor Freight Traffic Association, Inc. Statistics Canada Postal Code™ Conversion File which is based on data licensed from Canada Post Corporation. -

Washington's New Mount Rainier Scenic RAILROAD Steam, Passengers and Sceneru SOUTHERN PACIFIC BAY AREA STEAM by HARRE W

PUBLISHED MID-MAY, 1982 CONTAINING EARLY MAY NEWS C'P' ISSUE NUMBER 237 $2.00 ALSO In THIS ISSUE: WEYERHAEUSER'S CHEHALIS WESTERn LOGGER, WESTERn STEAM AnD MUCH MORE! WASHinGTOn'S nEW mounT RAiniER SCEniC RAILROAD Steam, passengers and sceneru SOUTHERN PACIFIC BAY AREA STEAM BY HARRE W. DEMORO When Cab-Forwards Passed Niles Tower Once they seemed to be everywhere, wh istling through Port Costa in the shadow of the high bluffs along Carquinez Strait, rumbling over the steel bridge across Alameda Creek at Niles, barking through the girders of the Dumbarton Bridge, taking commuters home along Seventh Street in Oakland, and to Burlingame, Palo Alto and Sa n Jose, south from Sa n Francisco. The steam engine has now vanished, but its spirit continues on the pages of this volume about the aromatic days of smoki ng Southern Pacific locomotives in the San Francisco Bay Area of California. Here is a collection of vintage photographs, the work of some of the best rail cameramen of the era is represented: artists such as R. H. McFarland, D. S. Richter, Will Whittaker, Ralph W. Demoro, John C. IIlman, Waldemar Sievers and Ted G. Wurm . Huge cab-forward s, Daylight 4-8-4's, tank locomoti ves, switch engines and the sturdy • Hardbound with a full-color dust little Consolidations are covered along with just about every type of steam locomotive $22.50 jacket photograph at Oakland Pier Southern Pacific operated in the Bay Area Plus 6% Sales Tax In California by Stan Kistler. 144 big 8'hx11" from the 1860's until diesels conquered . -

THE ROYAL Hudson HEADS SOUTH, a Mopae ROSTER Summary and More

CJX MARCH,1977 $1.00 ALSO In THIS ISSUE: THE ROYAL HUDson HEADS SOUTH, A mOPAe ROSTER SUmMARY AnD mORE. ,_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_1_._._1_1_1_._. ! NEVER MISS ANOTHER PHOTOGRAPH! I i DON'T EVER MISS ANOTHER RAILROAD EVENT; I I LISTEN ON YOUR OWN SCANNER : : Railroad Radio Scanning At Its Very I Best i • I I -,, ,-, EARCAT® RADIOS • ,__ B I I I "_, � ,/<'- -JIll, I - I: E 1-"0 -(�1 I The Bearcaf® Hand-Held Is B ARCAT I the ideal portable scanner for HAND-HELD � - access to public service and all � I railroad broadcasts. Four frequ"ncies can I be monitored at a time, using crystals, with � . an eight channel/second scan rate. Light ill� I I emitting diodes show channels monitored. �.� , • - I Fou��£R!�'�te'?!tf�l!,:$J��;.�g$4. -; I The Wh ole Worlo OPTIONAL ITEMS FOR SCANNERS Of Scanning Af Your ;� HAND HELD: Battery charger, AC adaptor, $8.95 each. I_ I The model� 210 is a Fingertips. ���i �: Flexible rubber antenna, $7.50. Crystal certificates, $4.00. sophisticated scanning instrument with! �!I! 1 BEARCAT MODEL Mobile power supply kit, $29.95. 1 101: frequency versatility as well as the operational I - I_ ease that you've been dreaming about. Imagine selecting from all of the public service bands, local service frequencies and railroad Most scanning monitors use a frequencies by simply pushing a few buttons. You can forget both specific crystal to receive each I I ...rystals and programming forever. Pick the ten frequencies you frequency. The 101 does not. It want to scan and punch the numbers in on the keyboard. -

AZ Bibliography.Pdf (11.20Mb)

17 September 2000 Memorandum To: Mary Ochs, Mann Library, Cornell University Fr: Doug Jones, Science-Engineering Lib, Univ of Arizona Su: Final Arizona bibliography for tJSAININEH project Enclosed is a copy ofthe final bibliography with average rank values attached consisting of 1150 items. 1. Book 1908 directory of Phoenix and the Salt River Valley including Tempe and Mesa, territory of Arizona: embracing a directory of the residents of Phoenix and additions, Tempe and Mesa, rural free delivery routes, giving their names, residence and business addresses, and occupations, together with a classified business directory: it contains a guide to the streets, halls, churches, lodges, schools, city, county, and territorial governments, etc., also data concerning the history, advantages, and existing conditions of Phoenix, Tempe and Mesa, and the great Salt RiverValley .Directory oiPhoenix and the Salt River Valley. Genealogy and local history; LH11624. 371 pages. Phoenix, Ariz.Phoenix Directory Co.8. OCLCIRLIN #: 39506270 . Catalog: OCLC. Holdings: Primary Location: No Holdings. Preservation & Microfilming Notes: Microfiche. Ann Arbor, Mich. : OMI, 1998.5 microfiche; 11 x 15 cm. (Genealogy and local history; LHl1624). Call #: No Information. Phoenix (Ariz.) -- Directories/Tempe (Ariz.) -- Directories/Mesa (Ariz.) -- Directories. Salt River Valley (Ariz.) -- Directories. Average Rank: 3.5. 2. Book Salt River Valley Water Users' Association.Agreement by and between Salt River Valley Water Users' Association and Local Union B-226 of Phoenix ofInternational Brotherhood of Electrical Workers A pages. Phoenix, Arizona?41. OCLCIRLIN #: 24866743. Catalog: OCLC. Holdings: Primary Location: AZP. Call #: 331.881 S17. Labor Laws and legislation - ArizonalTrade Unions - Arizona. Average Rank: 2.75. 3. Book Central Arizona Project Association, Phoenix, Arizona.The amazing story of Colorado River water in the Imperial Valley of California. -

Epes Randolph Advocating Arrangement

THE THRIFTY BUYER THE HOME PAPER will read what El Centrh mer- Always in everything puts chants have to say each day. El Centro and the Imperial ' or INDUSTRIAL TRADE AT HOME Valley first. INDEPENDENT'n PQI.ITICSi V; PROOBESSjj OFFICIAL PAPER OF THE CITY OF EL CENTRO AUGUST, 190* NUMBER 265 ESD AY EVENING, MARCH 14, 1917 DAILY STANDARD FOUNDED VOLUME XII VALLEY PRESS FOUNDED MAY, 1901 EL CENTRO, CALIFORNI A , WEDN President to Urge GERMANS SINKSTEAMER Recalled Gerard Prompt Action for BELONGING TO AMERICA Arrives at Capital and Remains Mute Defense Measures BULLET BOUNCES ALTHOUGH ALGONQUIN PARKER MYSTERY SUGGESTS UNIVERSAL BULLDOG CLEW OFF TIPPIN’S IS UNARMED SHE IS HASNOTBEEN SCHOOL GIRLS HANDED HIEMORANDI SERVICE AGO LEASES TORPEDOED WITHOUT TO CONDUCT FROM lITEHOUSE AS OF MINERALRESERVES TO MISSING CRAM' WARNING BY TEUTONS CLEARED CAUTION FOR SILENCE (By United Press) Unwritten Law T May Not Suspected Husband Manag- (By United Press) Press) Lonfton March 14.—The Amer- VILLAGE 14.—Forme- (By United Washington, March MACHINE reports ican consul that the Amer- Washington, March 14.—President Avail in Riehardson Case, es to Convince Author- Ambassador Gerard and party we ican steamer Algonquin, which Congress I Wilson’s message to the next route of Camp Fire Girls Promise met by cheering crowds when they a •* Brawley Declare the Authorities. was unarmed and en here ities Innocence. will urge the immediate consideration Ford Car Stolen in with foodstuffs, was torpedoed Much at Kermiss to Be rived here this afternoon. and prompt action on definite defense Has Interesting Angle Monday by the Germans. -

Arizona Rail Safety and Security Guide

State of Arizona Rail Safety & Security Resource Guide November 2007 Disclaimer This guide is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be an all-inclusive resource. The guide is a compilation of information from many sources and entities. The information contained herein is subject to amendment and change without notice and therefore the accuracy of the contents cannot be guaranteed. Readers are cautioned not to rely solely on the guide and should do further research to ensure accuracy of the information. Legal advice should be sought as appropriate. i Acknowledgement of Participants Arizona Corporation Commission (ACC) Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) Arizona Operation Lifesaver (AZOL) BNSF Railway (BNSF) Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Federal Railroad Administration (FRA-USDOT) Federal Highway Administration (FHWA-USDOT) Federal Motors Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) Governor’s Office of Highway Safety (GOHS) METRO (Light Rail) Transportation Safety Administration (TSA-DHS) Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR) ii Preface This plan will focus on targeted areas of railroad safety with emphasis on data driven, state specific needs identified by the “USDOT Highway-Rail Crossing Safety and Trespass Prevention Action Plan” developed by the United States Department of Transportation. Initially, the plan was developed to help guide efforts by federal and state governments, rail industry and public rail safety organizations to reduce train- vehicle collisions and trespass incidents. While the action plan does highlight specific programs and activities, it is intended to provide flexibility to the railroads, highways, public transit and communities in responding effectively to real world conditions. The action plan emphasizes a multi-modal approach for improving safety at the nation’s 277,722 highway-rail crossings, and preventing trespassing along more than 145,000 miles of track and right of way. -

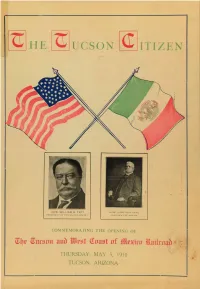

Ucson Itizei'p

z HE z UCSON ITIZEI‘P HON. PORFIRIO DIAZ PRESIDENT OF MEX•CO COMMEMORATING THE OPENING OF 0. ursi1fl an 1111 vit Toast of Moa n Naiirnab THURSDAY, MAY 5, 1910 TUCSON, ARIZONA CONSOLIDATED NATIONAL BANK TUCSON, ARIZONA United States Depositary. Depositary for all of the "Randolph Lines." Medium for the transfer of the funds of the Southern Pacific Company to the Treasurer. Special arrangement with the S. P. Company for th e cashing of any or all of their pay checks any place on the Tucson Division. Depositary for Wells Fargo Co . CONDENSED STATEMENT OF CONDITION MARCH 29, 1910 RESOURCES. LIABILITIES. Loans and Discounts ... ..$ .502,300.27 apital .. 50,000.00 United States Bonds 100,000.00 Stock $ ... 50,000.00 Bonds and Warrants 42,351.43 Surplus 22,657 31 Banking House ... 25,000.00 Cash in Vaults or With Circulation .. 50,000..00 Other Banks 610,052.18 Deposits . ..... 1,107,052.57 $1,279,709.88 $1,279,709.88 On March 15, 1890, under a charter from the Comptroller of the Currency, the Consolidated Bank of Tucson assumed its place among the National Banks RS The Consolidated National Bank.. Its deposits at that time were about $80,000. On the fifteenth ultimo, by reason of the expiration of its original charter, a new one extending its existence for another twenty years was received from the Comptroller. During the twenty years of its existence its line of deposits, as is shown by its last statement, has grown to over $1,100.000. A most flattering showing, in view of the fact that no interest is paid on deposits. -

Thirtieth Annual Report for the Year Ended June 30, 1919

Thirtieth Annual Report for the Year Ended June 30, 1919 Item Type text; Report Authors University of Arizona. Agricultural Experiment Station. Publisher College of Agriculture, University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Rights Public Domain: This material has been identified as being free of known restrictions under U.S. copyright law, including all related and neighboring rights. Download date 08/10/2021 12:04:10 Item License http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196596 University of Arizona College of Agriculture Agricultural Experiment Station Thirtieth Annual Report For the Year Ended June 30, 1919 (With subsequent Items) Consisting of reports relating to Administration Agricultiiral Chemistry, Agronomy, Animal Husbandry, Botany, Dairy Husbandry, Entomology, Horticulture, Irrigation Investigations, Plant Breeding, Poultry Husbandry Tucson, Arizona, December 31, 1919 REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY Ex-Officio His EXCELLENCY, THE GOVERNOR OF ARIZONA THE STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION Appointed by the Governor of the State EPES RANDOLPH President of the Board and Chancellor WILLIAM SCARLETT, A.B., B.D Regent JOHN H. CAMPBELL, LL.M Regent TIMOTHY A. RIORDAN Regent JAMES G. COMPTON Secretary WILLIAM JENNINGS BRYAN, JR., A.B Treasurer EDMUND W. WELLS • Regent Louis D. RICKETTS, SC.D., LL.D Regent AGRICULTURAL EXPERIMENT STATION STAFF *RUFUS B. VON KLEINSMID, A.M., SC.D. ... President of the University, Director **D. W. WORKING, B.SC, A.M Dean College of Agriculture, Director fROBERT H. FORBES, M.S., Ph.D Research Specialist JOHN J. THORNBER, A.M Botanist ALBERT. E. VINSON, Ph.D Chemist CLIFFORD N. CATLIN,* A.M Associate Chemist fHowARD W. -

Arizona T: Eastern;; Rai Troad Bridge HAER No

Arizona T: Eastern;; Rai Troad Bridge HAER No. HAER NO. AZ-18 (Southern7 P.aci fi c Ra.i 1 road Br.idge-) Spanning SattRiver lenipe ".- Marieopa County Arizona/. 2- PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA Historic American Engineering Record National Park Service Western Region Department of Interior San Francisco, California 94102 HISTORIC AMERICAN ENGINEERING RECORD Arizona Eastern Railroad Bridge (Southern Pacific Railroad Bridge) HAER No. AZ-18 Location Crossing Salt River at Tempe, Maricopa County, Arizona; Tempe Quadrangle 7.5': UTM coordinates X: 412,293; Y: 3,699,398, Arizona central zone. Date of Construction: 1905-1915. Present Owner: Southern Pacific Transp. Co. Southern Pacific Building One Market Plaza San Francisco, CA 94105 Present Use: Daily S,P. freight and Amtrak passenger use. Significance: Longest-standing railroad bridge at a location notorious for flood damage; last remaining railroad bridge in Tempe. Nine-span Pratt truss style illustrates evolution of bridge engineering of the era. Owned by two of Salt River Valley's most influential railroad companies. Historian: Barbara Behan, Research Archives, Salt River Project. Arizona Eastern R.R. Bridge (Southern Pacific R.R. Bridge) HAER No. AZ-18 2 The Southern Pacific Railroad has been an integral part of the history of Arizona as a territory and state. From the time of its original construction across southern Arizona in 1880, the company as well as its competitors have provided the transportation that enabled economic growth during the territorial and early statehood periods. It also was a major influence in the development of the state's most populous regions. The largest of these is the Salt River Valley, where irrigated agriculture flourished in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. -

Salton Sea California's Overlooked Treasure

The Salton Sea : California's Overlooked Treasure - Chapter 1 Page 1 of 14 Salton Sea: CA's Overlooked Basin-Delui \lothersite Salton Sea Home Page Treasure Laflin, P ., 1995 . 'the Salton Sea : California's overlooked treasure . The Periscope, Coachella Valley C Historical Society, Indio, California . 61 pp. (Reprinted in 1999) THE SALTON SEA CALIFORNIA'S OVERLOOKED TREASURE PART I BEFORE THE PRESENT SEA Chapter 1 THE SALTON SEA -- ITS BEGINNINGS The story of the Salton begins with the formation of a great shallow depression, or basin which modem explorers have called the Salton Sink. Several million years ago a long arm of the Pacific Ocean extended from the Gulf of California though the present Imperial and Coachella valleys, then northwesterly through the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys . Mountain ranges rose on either side of this great inland sea, and the whole area came up out of the water . Oyster beds in the San Felipe Mountains, on the west side of Imperial Valley are located many hundreds of feet above present sea level. Slowly the land in the central portion settled, and the area south of San Gorgonio Pass sloped gradually down to the Gulf. If it had not been affected by external forces, it would probably have kept its original contours, but it just so happened that on its eastern side there emptied one of the mightiest rivers of the North American continent the Colorado . The river built a delta across the upper part of the Gulf, turning that area into a great salt water lake . It covered almost 2100 square miles.