The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China Charles Horner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Major-General Jennie Carignan Enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986

MAJOR-GENERAL M.A.J. CARIGNAN, OMM, MSM, CD COMMANDING OFFICER OF NATO MISSION IRAQ Major-General Jennie Carignan enlisted in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) in 1986. In 1990, she graduated in Fuel and Materials Engineering from the Royal Military College of Canada and became a member of Canadian Military Engineers. Major-General Carignan commanded the 5th Combat Engineer Regiment, the Royal Military College in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, and the 2nd Canadian Division/Joint Task Force East. During her career, Major-General Carignan held various staff Positions, including that of Chief Engineer of the Multinational Division (Southwest) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and that of the instructor at the Canadian Land Forces Command and Staff College. Most recently, she served as Chief of Staff of the 4th Canadian Division and Chief of Staff of Army OPerations at the Canadian Special OPerations Forces Command Headquarters. She has ParticiPated in missions abroad in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Golan Heights, and Afghanistan. Major-General Carignan received her master’s degree in Military Arts and Sciences from the United States Army Command and General Staff College and the School of Advanced Military Studies. In 2016, she comPleted the National Security Program and was awarded the Generalissimo José-María Morelos Award as the first in her class. In addition, she was selected by her peers for her exemPlary qualities as an officer and was awarded the Kanwal Sethi Inukshuk Award. Major-General Carignan has a master’s degree in Business Administration from Université Laval. She is a reciPient of the Order of Military Merit and the Meritorious Service Medal from the Governor General of Canada. -

Language Loss Phenomenon in Taiwan: a Narrative Inquiry—Autobiography and Phenomenological Study

Language Loss Phenomenon in Taiwan: A Narrative Inquiry—Autobiography and Phenomenological Study By Wan-Hua Lai A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF EDUCATION Department of Curriculum, Teaching, and Learning University of Manitoba, Faculty of Education Winnipeg Copyright © 2012 by Wan-Hua Lai ii Table of Content Table of Content…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……ii List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………………………………..……...viii List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………………………………ix Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...xi Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………………………………………..…xii Dedication………………………………………………………………………………………………………………xiv Chapter One: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………….….1 Mandarin Research Project……………………………………………………………………………………2 Confusion about My Mother Tongue……………………………………………………….……………2 From Mandarin to Taigi………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Taiwan, a Colonial Land………………………………………………………………………………………..3 Study on the Language Loss in Taiwan………………………………………………………………….4 Archival Research………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Chapter Two: My Discovery- A Different History of Taiwan……………………………………….6 Geography…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….7 Population……………………………………………….…………………………………………………….……9 Culture…………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..9 Society………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………10 Education…………………………………………………………………………………………………….………11 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………….…………….………11 -

Soldiers and Statesmen

, SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number008-070-00335-0 Catalog Number D 301.78:970 The Military History Symposium is sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy 1970 Military History Symposium Steering Committee: Colonel Alfred F. Hurley, Chairman Lt. Colonel Elliott L. Johnson Major David MacIsaac, Executive Director Captain Donald W. Nelson, Deputy Director Captain Frederick L. Metcalf SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN The Proceedings of the 4th Military History Symposium United States Air Force Academy 22-23 October 1970 Edited by Monte D. Wright, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy and Lawrence J. Paszek, Office of Air Force History Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy Washington: 1973 The Military History Symposia of the USAF Academy 1. May 1967. Current Concepts in Military History. Proceedings not published. 2. May 1968. Command and Commanders in Modem Warfare. Proceedings published: Colorado Springs: USAF Academy, 1269; 2d ed., enlarged, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972. 3. May 1969. Science, Technology, and Warfare. Proceedings published: Washington, b.C.: Government Printing Office, 197 1. 4. October 1970. Soldiers and Statesmen. Present volume. 5. October 1972. The Military and Society. Proceedings to be published. Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy. -

The Generalissimo

the generalissimo ګ The Generalissimo Chiang Kai- shek and the Struggle for Modern China Jay Taylor the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, En gland 2009 .is Chiang Kai- shek’s surname ګ The character Copyright © 2009 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taylor, Jay, 1931– The generalissimo : Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China / Jay Taylor.—1st. ed. â p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 0- 674- 03338- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Chiang, Kai- shek, 1887–1975. 2. Presidents—China— Biography. 3. Presidents—Taiwan—Biography. 4. China—History—Republic, 1912–1949. 5. Taiwan—History—1945– I. Title. II. Title: Chiang Kai- shek and the struggle for modern China. DS777.488.C5T39 2009 951.04′2092—dc22 [B]â 2008040492 To John Taylor, my son, editor, and best friend Contents List of Mapsâ ix Acknowledgmentsâ xi Note on Romanizationâ xiii Prologueâ 1 I Revolution 1. A Neo- Confucian Youthâ 7 2. The Northern Expedition and Civil Warâ 49 3. The Nanking Decadeâ 97 II War of Resistance 4. The Long War Beginsâ 141 5. Chiang and His American Alliesâ 194 6. The China Theaterâ 245 7. Yalta, Manchuria, and Postwar Strategyâ 296 III Civil War 8. Chimera of Victoryâ 339 9. The Great Failureâ 378 viii Contents IV The Island 10. Streams in the Desertâ 411 11. Managing the Protectorâ 454 12. Shifting Dynamicsâ 503 13. Nixon and the Last Yearsâ 547 Epilogueâ 589 Notesâ 597 Indexâ 699 Maps Republican China, 1928â 80–81 China, 1929â 87 Allied Retreat, First Burma Campaign, April–May 1942â 206 China, 1944â 293 Acknowledgments Extensive travel, interviews, and research in Taiwan and China over five years made this book possible. -

On the Commander-In-Chief Power

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2008 On the Commander-In-Chief Power David Luban Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 1026302 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/598 http://ssrn.com/abstract=1026302 81 S. Cal. L. Rev. 477-571 (2008) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons ON THE COMMANDER IN CHIEF POWER ∗ DAVID LUBAN BRADBURY: Obviously, the Hamdan decision, Senator, does implicitly recognize that we’re in a war, that the President’s war powers were triggered by the attacks on the country, and that [the] law of war paradigm applies. That’s what the whole case was about. LEAHY: Was the President right or was he wrong? BRADBURY: It’s under the law of war that we . LEAHY: Was the President right or was he wrong? BRADBURY: . hold the President is always right, Senator. —exchange between a U.S. Senator and a Justice Department 1 lawyer ∗ University Professor and Professor of Law and Philosophy, Georgetown University. I owe thanks to John Partridge and Sebastian Kaplan-Sears for excellent research assistance; to Greg Reichberg, Bill Mengel, and Tim Sellers for clarifying several points of American, Roman, and military history; to Marty Lederman for innumerable helpful and critical conversations; and to Vicki Jackson, Paul Kahn, Larry Solum, and Amy Sepinwall for helpful comments on an earlier draft. -

Chiang Kai-Shek Introduction General Overviews Primary Sources

Chiang Kai-Shek Introduction General Overviews Primary Sources Archives Collected Works and Books Other Primary Sources Collections of Visual Sources Journals Historiographical Overviews Biographies Upbringing and Early Career Rise to Power and the “Chinese Revolution” Nanjing Decade Relationship with Japan Second Sino-Japanese War Civil War and “Loss” of the Mainland Chiang Kai-shek on Taiwan Cold War Personality Cult, Commemoration, and Legacy Introduction Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi 蔣介石)—also referred to as Chiang Chung-cheng (Jiang Zhongzheng 蔣 中正)—is one of the most controversial figures in modern Chinese history. He is also one of the most studied. He has been the focus of a vast array of historiography, biography, hagiography, and demonization. For early critics, Chiang was seen, from his purging of the Communists in 1927, as a “betrayer” of the Chinese Revolution. This assessment is now a point of considerable contention among historians. His creation of a unified yet authoritarian Chinese state during the Nanjing Decade (1927–1937) is also a prominent focus of scholarship, as is his role as China’s leader during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945). Earlier assessments often ended their study of Chiang with his defeat by the communists in the Chinese Civil War and his subsequent flight to Taiwan in 1949. However, more recent scholarship has explored both the controversies and achievements of the quarter of a century that Chiang spent on Taiwan, and his legacy on that island in the period since 1975. There remain major differences in approaches to the study of Chiang along political, methodological, and national lines, but the deposition of Chiang’s diaries at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University, in 2004 has ensured that a steady flow of scholarly reassessments has been published since then. -

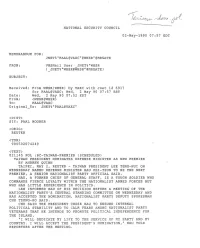

"PAAL@VAXC"@WHSR"@MRGATE FROM: Vmsmail User JNET%"WHSR ( JNET%"WHSR@WHSR"@MRGATE) SUBJECT

NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL 02-May-1990 07:57 EDT MEMORANDUM FOR: JNET%"PAAL@VAXC"@WHSR"@MRGATE FROM: VMSMail User _JNET%"WHSR (_JNET%"WHSR@WHSR"@MRGATE) SUBJECT: Received: From WHSR(WHSR) by VAXC with Jnet id 6917 for PAAL@VAXC; Wed, 2 May 90 07:57 EST Date: Wed, 2 May 90 07:52 EST From: <WHSR@WHSR> To: PAAL@VAXC Original To: JNET%"PAAL@VAXC" <DIST> SIT: PAAL MOORER <ORIG> REUTER <TOR> 900502074249 <TEXT> 021145 POL :BC-TAIWAN-PREMIER (SCHEDULED) TAIWAN PRESIDENT NOMINATES DEFENSE MINISTER AS NEW PREMIER BY ANDREW QUINN TAIPEI, MAY 2, REUTER - TAIWAN PRESIDENT LEE TENG-HUI ON WEDNESDAY NAMED DEFENSE MINISTER HAU PEI-TSUN TO BE THE NEXT PREMIER, A SENIOR NATIONALIST PARTY OFFICIAL SAID. HAU, A FORMER CHIEF OF GENERAL STAFF, IS A TOUGH SOLDIER WHO COMMANDS FIERCE LOYALTY WITHIN THE NATIONALIST ARMED FORCES BUT WHO HAS LITTLE EXPERIENCE IN POLITICS. LEE INFORMED HAU OF HIS DECISION BEFORE A MEETING OF THE NATIONALIST PARTY'S CENTRAL STANDING COMMITTEE ON WEDNESDAY AND HAU ACCEPTED THE NOMINATION, NATIONALIST PARTY DEPUTY SPOKESMAN CHU TZONG-KO SAID. CHU SAID THE PRESIDENT CHOSE HAU TO ENSURE INTERNAL POLITICAL STABILITY AND TO CALM FEARS AMONG NATIONALIST PARTY VETERANS THAT HE INTENDS TO PROMOTE POLITICAL INDEPENDENCE FOR THE ISLAND. "I WILL DEDICATE MY LIFE TO THE SERVICE OF MY PARTY AND MY COUNTRY. I WILL ACCEPT THE PRESIDENT'S NOMINATION," HAU TOLD REPORTERS AFTER THE MEETING. A FOUR-STAR GENERAL, HAU WAS THE MUSCLE BEHIND THE CHIANG FAMILY DYNASTY, BEGUN BY THE LATE GENERALISSIMO CHIANG KAI-SHEK, WHICH RULED TAIWAN FOR ALMOST FOUR DECADES. -

Africa to the Alps the Army Air Forces in the Mediterranean Theater

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II Africa to the Alps The Army Air Forces in the Mediterranean Theater Edward T. Russell and Robert M. Johnson AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM 1999 Africa to the Alps The Army Air Forces in the Mediterranean Theater By the time the United States declared war on Germany and Italy on December 11, 1941, most of Europe had fallen under the domination of Adolf Hitler, dictator of Germany’s Third Reich. In the west, only Great Britain, her armies expelled from the European continent, re- mained defiant; in the east, Hitler faced an implacable foe—the Sovi- et Union.While the Soviets tried to stave off a relentless German at- tack that had reached Moscow, Britain and her Commonwealth allies fought a series of crucial battles with Axis forces in North Africa. Initially, America’s entry into the war changed nothing. The Unit- ed States continued to supply the Allies with the tools of war, as it had since the passage of the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941. U.S. military forces, however, had to be expanded, trained, equipped, and deployed, all of which would take time. With the United States in the war, the Allies faced the question of where American forces could best be used. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston S. Churchill had al- ready agreed that defeating first Germany and then Japan would be their policy, but that decision raised further questions. Roosevelt wanted U.S. troops in combat against German troops as soon as possible. -

American-Educated Chinese Students and Their Impact on U.S.-China Relations" (2009)

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2009 American-educated Chinese Students and Their Impact on U.S.- China Relations Joshua A. Litten College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Litten, Joshua A., "American-educated Chinese Students and Their Impact on U.S.-China Relations" (2009). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 256. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/256 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN-EDUCATED CHINESE STUDENTS AND THEIR IMPACT ON U.S.-CHINA RELATIONS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors in History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Joshua A. Litten Accepted for __________________ Craig Canning___ Director Eric Han________ T.J. Cheng_______ Williamsburg, Virginia May 2009 1 Table of Contents Introduction…………………………………………………………………………....................... 3 Chapter 1: The Forerunners…………………………………………………………...................... 7 Yung Wing and the Chinese Educational Mission, 1847 – 1900 Chapter 2: “Unofficial Envoys”…………………………………………………………………… 29 The Boxer Indemnity Scholarships, 1900 – 1949 Chapter -

Planet China

1 Talking Point 6 Week in 60 Seconds 7 Telecoms Week in China 8 Banking and Finance 9 Economy 11 China and the World 13 Shipping 14 Society and Culture 27 November 2015 19 And Finally Issue 305 20 The Back Page www.weekinchina.com Clash of the internet kingdoms m o c . n i e t s p e a t i n e b . w w w In a flurry of recent dealmaking Baidu’s Robin Li looks to make up ground on bigger rivals Brought to you by Week in China Talking Point 27 November 2015 Searching for answers A new era as Baidu enters banking with Citic and insurance with Allianz? In the spotlight: Baidu’s founder Robin Li is looking to catch up with rivals Alibaba and Tencent hen Forbes ranked China’s The rivalry between the BAT trio – acquisitions and dealmaking. But Wrichest tycoons a year ago, which are seeking to dominate after its unexpected coup last the top three slots were taken by China’s internet – is frequently com - week – in linking itself to a major the founders of Baidu, Alibaba and pared to a period in the third cen - state-run bank – might Baidu re - Tencent – the internet giants tury when the states of Wei, Shu and gain the upper hand in its battles known locally by the acronym BAT. Wu battled for supremacy. The era, with Alibaba and Tencent? At that time Baidu’s chief executive known as the Three Kingdoms, was Robin Li was the second richest a particularly bloody chapter in his - A more eventful year for Baidu? man, just behind Jack Ma of Alibaba tory, characterised by battles for ter - Baidu started 2015 with a bang, in - but ahead of Tencent’s Pony Ma. -

Education, Fascism, and the Catholic Church in Franco's Spain

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 Education, Fascism, and the Catholic Church in Franco's Spain Joan Domke Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Educational Administration and Supervision Commons Recommended Citation Domke, Joan, "Education, Fascism, and the Catholic Church in Franco's Spain" (2011). Dissertations. 104. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/104 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Joan Domke LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO EDUCATION, FASCISM, AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH IN FRANCO‟S SPAIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL POLICY STUDIES BY JOAN CICERO DOMKE CHICAGO, IL MAY 2011 Copyright by Joan Domke, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Sr. Salvador Vergara, of the Instituto Cervantes in Chicago, for his untiring assistance in providing the most current and pertinent sources for this study. Also, Mrs. Nicia Irwin, of Team Expansion in Granada, Spain, made it possible, through her network of contacts, for present-day Spaniards to be an integral part in this research. Dr. Katherine Carroll gave me invaluable advice in the writing of the manuscript and Dr. John Cicero helped in the area of data analysis. -

The Murder of Henry Liu

Published by: International Committee for Human Rights in Taiwan Europe : P.O. Box 91542, 2509 EC THE HAGUE, The Netherlands U.S.A. : P.O. Box 45205, SEATTLE, Washington 98105-0205 European edition, April 1985 Published 6 times a year 19 ISSN number: 1027-3999 The murder of Henry Liu On 15 October 1984, Mr. Henry Liu, a prominent Chinese-American journalist, was murdered at his home in Daly City, a suburb of San Francisco. The case has received wide international attention because of the subsequent revelations that the murder was committed by three underworld figures from Taiwan on the order of top-officials of the Military Intelligence Bureau of the Ministry of Defense. Furthermore, there are allegations that a link existed between the leader of the underworld gang, Mr. Chen Chi-li, and the second son of President Chiang Ching-kuo, Mr. Chiang Hsiao-wu. Below, we first present a chronological overview of the developments, which have taken place since our previous report on this case (see Taiwan Communiqué no. 18): Chronological overview a. On 7 February 1985, the Subcommittee on Asian and Pacific Affairs of the U.S. House of Representatives held a hearing in Washington D. C. At this hearing a number of persons -- including Mr. Liu’s courageous widow Helen Liu -- presented testimony, in particular regarding the possible motives for the murder. b. On 24 February 1985, the San Francisco Examiner reported that the person accused of masterminding the murder, Bamboo Union gangleader Chen Chi-li, had admitted to planning the killing with three top-officials of the Military Intelligence Bureau of the Ministry of Defense.