Special Journals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A73 Cash Basis Accounting

World A73 Cash Basis Accounting Net Change with new Cash Basis Accounting program: The following table lists the enhancements that have been made to the Cash Basis Accounting program as of A7.3 cum 15 and A8.1 cum 6. CHANGE EXPLANATION AND BENEFIT Batch Type Previously cash basis batches were assigned a batch type of ‘G’. Now cash basis batches have a batch type of ‘CB’, making it easier to distinguish cash basis batches from general ledger batches. Batch Creation Previously, if creating cash basis entries for all eligible transactions, all cash basis entries would be created in one batch. Now cash basis entries will be in separate batches based on a one-to-one batch ratio with the originating AA ledger batch. For example, if cash basis entries were created from 5 separate AA ledger batches, there will be 5 resulting AZ ledger batches. This will make it simpler to track posting issues as well as alleviate problems inquiring on cash basis entries where there were potential duplicate document numbers/types within the same batch. Batch Number Previously cash basis batch numbers were unique in relation to the AA ledger batch that corresponded to the cash basis entries. Now the cash basis batch number will match the original AA ledger batch, making it easier to track and audit cash basis entries in relation to the originating transactions. Credit Note Prior to A7.3 cum 14/A8.1 cum 4, the option to assign a document type Reimbursement other than PA to the voucher generated for reimbursement did not exist. -

Accounting I

Accounting I Course Text Wild, John J., Kermit D. Larson, and Barbara Chiapetta. Fundamental Accounting Principles, Volume 1, 18th edition. McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2007. ISBN 0-07-328661-3 Course Description This course focuses on ways in which accounting principles are used in business operations. Students learn to identify and use Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), ledgers and journals throughout the steps of the accounting cycle. This course introduces bank reconciliation methods, balance sheets, assets, and liabilities. Students also learn about financial statements including assets, liabilities, and equity. Business ethics are also discussed. Course Objectives After completing this course, students will be able to: • Identify and apply Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). • Apply the steps of the accounting cycle. • Post and analyze transactions using ledgers and journals. • Record adjusting entries for prepaid expenses and unearned revenue. • Complete an adjusted trial balance. • Perform a bank reconciliation. • Explain the purpose of the sales journal and the Accounts Receivable ledger and post entries to both. • Record the costs associated with the acquisition of property, plant, and equipment. • Explain the purpose of and prepare entries for the purchase order journal and accounts payable (A/P) ledger. • Identify the fundamental principles of an accounting information system. Course Prerequisites There are no prerequisites to take Accounting I. Course Evaluation Criteria StraighterLine does not apply letter grades. Students earn a score as a percentage of 100%. A passing percentage is 70% or higher. If you have chosen a Partner College to award credit for this course, your final grade will be based upon that college's grading scale. -

Consolidation-Date of Acquisition

Consolidation-Date of Acquisition Chapter 4 • Consolidated statements bring together the operating results and financial position of two or more separate legal entities into a single set of Consolidation As statements for the economic entity as a whole. Of The Date Of Acquisition • To accomplish this, the consolidation process includes procedures that eliminate all effects of intercorporate ownership and intercompany transactions. McGraw-Hill/Irwin Copyright © 2005 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 4-2 Consolidation-Date of Acquisition Consolidation-GAAP • The procedures used in accounting for intercorporate investments were discussed in Chapter 2. • These procedures are important for the preparation of consolidated statements because • Consolidated and unconsolidated financial the specific consolidation procedures depend on statements are prepared using the same the way in which the parent accounts for its generally accepted accounting principles. investment in a subsidiary. • The consolidated statements, however, are the same regardless of the method used by the parent company to account for the investment. 4-3 4-4 Roadmap—Chapter 4 Roadmap—Chapters 5 to 10 • After introducing the consolidation workpaper, • Chapter 5 includes the preparation of a full set of this chapter provides the foundation for an consolidated financial statements in subsequent understanding of the preparation of consolidated periods, that is, after the date of acquisition. financial statements by discussing the preparation of a consolidated balance sheet immediately following the establishment of a • Chapters 6 through 10 deal with intercorporate parent-subsidiary relationship. transfers and other more complex topics. 4-5 4-6 1 Consolidation Workpapers Consolidation Workpapers • The consolidation workpaper provides a • The parent and its subsidiaries, as separate mechanism for efficiently combining the legal and accounting entities, each maintain accounts of the separate companies involved in their own books. -

Workflow and Process Control – Charles Hoffman, Cpa

MASTERING XBRL-BASED DIGITAL FINANCIAL REPORTING – PART 3: WORKING WITH DIGITAL FINANCIAL REPORTS – WORKFLOW AND PROCESS CONTROL – CHARLES HOFFMAN, CPA 1. Workflow and Process Control The purpose of this section is to discuss the workflow and process control related to the creation of XBRL-based digital financial reports. A financial report is the end of a process from the perspective of a reporting entity. That is exactly correct from the perspective of a reporting entity. But, from the perspective of a financial analyst that is making use of the reported information, the financial report is the beginning of a process. Perspective matters. What we are working with here is not a “silo”, rather it is more of a “chain”. This section shows you how you create an XBRL-based digital financial report. Many times, reports will be automatically generated from an accounting system. 1.1. Workflow Basics Per Wikipedia, workflow is defined as, “A workflow consists of an orchestrated and repeatable pattern of activity, enabled by the systematic organization of resources into processes that transform materials, provide services, or process information.1” From a computer science perspective, workflow is “The computerised facilitation or automation of a business process, in whole or part2”. From a computer science perspective, workflow is concerned with the automation of procedures where documents, information or tasks are passed between participants according to a defined set of rules to achieve, or contribute to, an overall business goal.” Workflow is often associated with Business Process Management, which is concerned with the assessment, analysis, modelling, definition and subsequent operational implementation of the core business processes of an organisation (or other business entity). -

Accounting for a Service Business Organized As a Proprietorship (Chapters 2 – 10)

Unit 1: Accounting for a Service Business Organized as a Proprietorship (Chapters 2 – 10) I. Analyzing Business Transactions A. Effect of business transactions on the fundamental accounting equation B. Principles of debit and credit C. Recording balances in the account (opening entry) D. Recording changes in asset liability and owner’s equity accounts II. Journalizing (Chapter 5) A. General Journal (book of original entry) B. Source documents C. Journalizing Procedures 1. Date 2. Titles of the accounts to be debited and credited 3. Amounts of the debits and credits 4. Source Document (cross- reference for auditing) D. Error Correction (Chapter 8 - pp.183-187) III. Posting (Chapter 6) A. Chart of Accounts B. General Ledger C. Ledger account format (four amount columns) 1. Account Title 2. Account Number 3. Date Accounting – Unit 1 – p. 1 4. Item 5. Posting Reference 6. Debit 7. Credit 8. Debit Balance 9. Credit Balance D. Opening an account E. Journal to general ledger posting 1. Recording Date 2. Amount of the debit or credit 3. Amount of the debit or credit balance 4. Posting References (In general ledger AND general journal) IV. Cash Control Systems (Banking and Petty Cash) (Chapter 7 & Checking Account Simulation Packet Provided By Rome Savings Bank) A. Checking Accounts 1. Opening an account - Authorizing Signatures 2. Preparing Checks a) Parts of a check b) Preparing Check Stubs/Check Register c) Voiding a check 3. Depositing Cash 4. Endorsing Checks a) Blank endorsement Accounting – Unit 1 – p. 2 b) Special endorsement c) Restrictive endorsement B. Bank Statements 1. Verifying a Bank Statement 2. -

Basic Accounting Terminology: • Event: a Happening Or Consequence

GOVERNMENTAL ACCOUNTING All those involved in the oversight or management of government operations, and those whose livelihood and interest rely on the finances of local governments, need to have a clear understanding of governmental accounting, auditing, and financial reporting which are based on a sound set of principles and interrelated practices and procedures. Accounting, financial reporting, and the financial statement audit provide the informational infrastructure of public finance. Accountability: Term used by GASB to describe a government’s duty to justify the raising and spending of public resources. The GASB has identified accountability as the “paramount objective” of financial reporting “from which all other objectives must flow”. Accounting and financial reporting (primarily the responsibility of management) are complementary rather than identical. Accounting: The process of assembling, analyzing, classifying, and recording data relevant to a government’s finances. Financial reporting: “Accounting” and “financial reporting” are similar but distinctly different terms that are often used together. The process of taking the information thus assembled, analyzed, classified, and recorded and providing it in usable form to those who need it. Financial reporting can take one of three forms: internal financial reporting (management reports), special purpose financial reporting (outside parties), and general purpose external financial reporting (GPEFR). The nationally recognized standards that govern GPEFR are known as generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). 1 Display: The display method of communication provides that items are reported as dollar amounts on the face of the financial statements if they both 1) meet the definition of one of the seven financial statement elements and 2) can be reliably measured. -

Experiential Learning Portfolio for 10101101 Financial Accounting 1

Experiential Learning Portfolio for 10101101 Financial Accounting 1 Student Contact Information: Name: _________________________________________Student ID#____________________ Email: _________________________________________Phone:________________________ It is required that you speak with the Academic Dean or instructor who teaches this course prior to completing a portfolio. Directions Consider your prior work, military, volunteer, education, training and/or other life experiences as they relate to each competency and its learning objectives. Courses with competencies that include speeches, oral presentations, or skill demonstrations may require scheduling face-to- face sessions. You can complete all of your work within this document using the same font, following the template format. 1. Complete the Student Contact Information at the top of this page. 2. Write an Introduction to the portfolio. Briefly introduce yourself to the reviewer summarizing your experiences related to this course and your future goals. 3. Complete each “Describe your learning and experience with this competency” section in the space below each competency and its criteria and learning objectives. Focus on the following: • What did you learn? • How did you learn through your experience? • How has that learning impacted your work and/or life? 4. Compile all required and any suggested artifacts (documents and other products that demonstrate learning). • Label artifacts as noted in the competency • Scan paper artifacts • Provide links to video artifacts • Attach all artifacts to the end of the portfolio 5. Write a Conclusion for your portfolio. Briefly summarize how you have met the competencies. 6. Proofread. Overall appearance, organization, spelling, and grammar will be considered in the review of the portfolio. 7. Complete the Learning Source Table. -

Solutions to Questions for Chap 6

CHAPTER 6 Accounting Information Systems ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS 01. (a) An accounting information system involves collecting and processing data and disseminating financial information. (b) Disagree. An accounting information system applies regardless of whether manual or com- puterized procedures are used to process the transaction data. 02. There are three principles for developing an accounting information system: Cost awareness. The system must be cost-effective; that is, the benefits obtained from the infor- mation disseminated must outweigh the cost of providing it. Useful output. To be useful, information must be understandable, relevant, reliable, timely, and accurate. Flexibility. The system should be able to accommodate a variety of users and changing informa- tion needs. 03. Cost awareness—The system must be cost-effective; that is, the benefits obtained from the infor- mation disseminated must outweigh the cost of providing it. In this case, the cost appears to out- weigh the benefits. 04. The phases of an accounting system are: Analysis, which involves planning and identifying information needs and sources. Design, which includes creating forms, documents, procedures, job descriptions, and reports. Implementation, which consists of installing the system, training personnel, and making the system wholly operational. Follow-up, which involves evaluating and monitoring effectiveness and efficiency and correcting any weaknesses. 05. A subsidiary ledger is a group of accounts with a common characteristic. The accounts are as- sembled together to facilitate the accounting process by freeing the general ledger from details concerning individual balances. The advantages of using subsidiary ledgers are that they: < Permit transactions affecting a single customer or single creditor to be shown in a single account, thus providing necessary up-to-date information on specific account balances. -

Growing Pains at Groupon

ISSUES IN ACCOUNTING EDUCATION American Accounting Association Vol. 29, No. 1 DOI: 10.2308/iace-50595 2014 pp. 229–245 Growing Pains at Groupon Saurav K. Dutta, Dennis H. Caplan, and David J. Marcinko ABSTRACT: On November 4, 2011, Groupon Inc. went public with an initial market capitalization of $13 billion. The business was formed a couple of years earlier as an offshoot of ‘‘The Point.’’ The business grew rapidly and increased its reported revenue from $14.5 million in 2009 to $1.6 billion in 2011. Soon after going public, prior to its announcement of its first-quarter results, the company’s auditors required Groupon to disclose a material weakness in its internal controls over financial reporting that impacted its disclosures on revenue and its estimation of returns. This case uses Groupon to motivate discussion of financial reporting issues in e- commerce businesses. Specifically, the case focuses on (1) revenue recognition practices for ‘‘agency’’ type e-commerce businesses, (2) accounting for sales with a right of return for new products, and (3) use of alternative financial metrics to better convey the intrinsic value of a business. The case requires students to critically read, analyze, and apply authoritative accounting guidance, and to read and analyze communications between the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the registrant. Keywords: Groupon; revenue recognition; allowance for sales returns; e-commerce; non-GAAP metrics. GROWING PAINS AT GROUPON s an undergraduate music major at Northwestern University, Andrew Mason eagerly sought a version of rock music that would fuse punk with the Beatles and Cat Stevens. -

Business Accounting Records .Dennis E

THE EVALUATION OF MODERN BUSINESS ACCOUNTING RECORDS .DENNIS E. MEISSNER Evaluation of record series for the purpose of bulk reduction is one of the more salient professional responsibilities facing archi- vists today. Problems imposed by bulk become especially vexatious in the cases of large modern business organizations, in great part due to the many series of accounting records created to control and monitor the financial workings of a company. How many of these records must we retain in order to preserve an accurate picture of the financial history of a business organization? Among some sixty articles and book chapters published over the• past forty years relating to business archives and business records, fewer than one-fourth offered any practical appraisal guidelines, and only one-third of that fraction were concerned to any extent with accounting records.' Most appraisal recommendations per- tained instead to narrative format business records such as the sundry levels of corporate correspondence and memoranda; the various series of minutes, annual reports, corporate periodicals, and other publications; publicity releases and news clippings; and other largely textual records. Those pertaining to accounting records tended to make specific retention prescriptions without providing any rationale for so doing. Furthermore, not all writers agree on what particular records should be preserved. As a beginning attempt to fill the apparent void, this paper will describe accounting records common to business in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries and will suggest ways to define their archival value. There are a few general principles for evaluating accounting records. The first principle is that a sufficient combination of ac- counting records should be kept so as to document completely the revenues, expenses, and net financial picture of the business at any point in its existence, and also to document the accounting methods 76 THE MIDWESTERN ARCHIVIST Vol. -

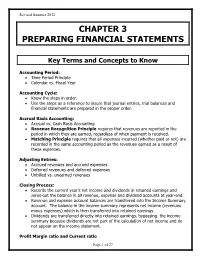

Chapter 3 Preparing Financial Statements

Revised Summer 2012 CHAPTER 3 PREPARING FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Key Terms and Concepts to Know Accounting Period: Time Period Principle Calendar vs. Fiscal Year Accounting Cycle: Know the steps in order. Use the steps as a reference to insure that journal entries, trial balances and financial statements are prepared in the proper order. Accrual Basis Accounting: Accrual vs. Cash Basis Accounting Revenue Recognition Principle requires that revenues are reported in the period in which they are earned, regardless of when payment is received. Matching Principle requires that all expenses incurred (whether paid or not) are recorded in the same accounting period as the revenues earned as a result of these expenses. Adjusting Entries: Accrued revenues and accrued expenses Deferred revenues and deferred expenses Unbilled vs. unearned revenues Closing Process: Records the current year’s net income and dividends in retained earnings and zeros-out the balance in all revenue, expense and dividend accounts at year-end. Revenue and expense account balances are transferred into the Income Summary account. The balance in the income summary represents net income (revenues minus expenses) which is then transferred into retained earnings. Dividends are transferred directly into retained earnings, bypassing the income summary because dividends are not part of the calculation of net income and do not appear on the income statement. Profit Margin ratio and Current ratio Page 1 of 27 Revised Summer 2012 Key Topics to Know Adjusting Entries Adjusting entries are required to record internal transactions and to bring assets and liability accounts to their proper balances and record expenses or revenues in the proper accounting period. -

General Ledger Vs General Journal: What Is the Difference?

What’s The Difference Between General Ledger and General Journal? General Ledger Vs General Journal: What Is The Difference? When it comes to business finances, using a double-entry system that makes use of both a general ledger and a general journal is the best method for checking overall statistics and keeping things running smoothly and profitably. But to understand how a double-entry accounting system, or double-entry bookkeeping works, it is first necessary to understand the different functions associated with the general ledger and the general journal. https://planergy.com/blog/general-ledger-vs-general-journal/ 1 / 6 The General Ledger The general ledger, also known as the book of second entry. It is used to track assets, liabilities, owner capital, revenues, and expenses. It is a book or file used to record all relevant accounts. Each account is a two-columns in a T shaped table where the book taper typically places the account title at the top of the T while recording that debit entries on the left side and credit entries on the right. Sometimes, you’ll find that the general ledger displays additional columns for particulars such as a description of the transaction, serial number, and date. Transactions from general journals are posted in the general ledger accounts and then balances are calculated and transferred from the general ledger to a trial balance. You also use it to create the chart of accounts, or the list of all the accounts used in the organization’s general ledger. The act of recording a transaction in the ledger is called posting.