Udc 327 the Cherkessk Issue in the South Russia: Inner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches. -

Combatting and Preventing Corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How Anti-Corruption Measures Can Promote Democracy and the Rule of Law

Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Silvia Stöber Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 4 Contents Contents 1. Instead of a preface: Why (read) this study? 9 2. Introduction 11 2.1 Methodology 11 2.2 Corruption 11 2.2.1 Consequences of corruption 12 2.2.2 Forms of corruption 13 2.3 Combatting corruption 13 2.4 References 14 3. Executive Summaries 15 3.1 Armenia – A promising change of power 15 3.2 Azerbaijan – Retaining power and preventing petty corruption 16 3.3 Georgia – An anti-corruption role model with dents 18 4. Armenia 22 4.1 Introduction to the current situation 22 4.2 Historical background 24 4.2.1 Consolidation of the oligarchic system 25 4.2.2 Lack of trust in the government 25 4.3 The Pashinyan government’s anti-corruption measures 27 4.3.1 Background conditions 27 4.3.2 Measures to combat grand corruption 28 4.3.3 Judiciary 30 4.3.4 Monopoly structures in the economy 31 4.4 Petty corruption 33 4.4.1 Higher education 33 4.4.2 Health-care sector 34 4.4.3 Law enforcement 35 4.5 International implications 36 4.5.1 Organized crime and money laundering 36 4.5.2 Migration and asylum 36 4.6 References 37 5 Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 5. -

Caucasus Maps

^ ^ ") Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Stavropol' Russian ") ^ ^ Armavir RUSSIA Lak Languages of the Avar ") ") Nevinnomyssk Dargwa Caucasus Region ^Maykop Adyghe Adyghe Russian Avar Lak KAZAKHSTAN Abaza ^Cherkessk Chechen ") Pyatigorsk Kislovodsk") Avar ^") Adyghe Nogai Aktau Sochi Kabardian ") Ingush ") Lak Karachay-Balkar ^ Russian Avar Nal'chik ^ Dargwa ") Abkhaz Nazran'^ Groznyy Khasav'yurt Dargwa ") Caspian Georgian Vladikavkaz^ Chechen ^Makhachkala ^ Sea Svan Botlikh Andi Kumyk Sokhumi Ghodoberi ² Karata Hinukh Avar Chechen Tabassaran Abkhaz Georgian Chamalal Archi Mingrelian Osetin Bagvalal Dargwa Osetin Tindi Akhvakh ") K'ut'aisi Bats Dido Khvarshi ") Derbent Black Hunzib Lak Aghul Sea GEORGIA Northern Bezhta Kurdish Tsakhur North Georgian Avar Azerbaijani Osetin ^ Tsakhur Lezgi Bat'umi T'bilisi Georgian Budukh ^ Laz ")Rust'avi Rutul Source of Language Area Boundaries: North Lezgi Note: Grey areas are Global Mapping International -- World Judeo-Tat areas for which there is Azerbaijani Tsakhur Language Mapping System Armenian Budukh no language information. ^ Khinalugh Kryts ^ Abkhaz Muslim Tat Laz Rutul ^ ^ Artvin North Lezgi ^ Rize ") Azerbaijani Udi ^ Trabzon (Coruh) ") Georgian Vanadzor Ganca ") ") Kars Gyumri Sumqayit ^ ARMENIA North Azerbaijani ^ Gumushane Baku^ ^ Turkish Armenian South Armenian AZERBAIJAN ^ ^ Azerbaijani ^Yerevan TURKEY North Northern Kurdish Erzurum South Azerbaijani ^ Azerbaijani ") Erzincan Agri^ North Azerbaijani ^ ^ Turkmen Parsabad AZERBAIJAN Northern Kurdish South Northern Kurdish ^Naxcivan Azerbaijani Tunceli -

Chechnya's Status Within the Russian

SWP Research Paper Uwe Halbach Chechnya’s Status within the Russian Federation Ramzan Kadyrov’s Private State and Vladimir Putin’s Federal “Power Vertical” Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs SWP Research Paper 2 May 2018 In the run-up to the Russian presidential elections on 18 March 2018, the Kremlin further tightened the federal “vertical of power” that Vladimir Putin has developed since 2000. In the North Caucasus, this above all concerns the republic of Dagestan. Moscow intervened with a powerful purge, replacing the entire political leadership. The situation in Chechnya, which has been ruled by Ramzan Kadyrov since 2007, is conspicuously different. From the early 2000s onwards, President Putin conducted a policy of “Chechenisation” there, delegating the fight against the armed revolt to local security forces. Under Putin’s protection, the republic gained a leadership which is now publicly referred to by Russians as the “Chechen Khanate”, among other similar expressions. Kadyrov’s breadth of power encompasses an independ- ent foreign policy, which is primarily orientated towards the Middle East. Kadyrov emphatically professes that his republic is part of Russia and presents himself as “Putin’s foot soldier”. Yet he has also transformed the federal subject of Chechnya into a private state. The ambiguous relationship between this republic and the central power fundamentally rests on the loyalty pact between Putin and Kadyrov. However, criticism of this arrange- ment can now occasionally be heard even in the Russian president’s inner circles. With regard to Putin’s fourth term, the question arises just how long the pact will last. -

Church – Consolidating the Georgian Regions

Church – Consolidating the Georgian Regions Metropolitan Ananya Japaridze Saint Ilia the Righteous said from the very establishment of the holy Church of Georgia, that it presented a strong power consolidating the whole population of the state. It was not locked within the narrow ethnic borders but was the belonging of different ethnos residing in the state. According to Holy Writ, it never differentiated Hellenist from Jew, Georgian from non-Georgian, as its flocks were children of Georgia with mutual responsibility to the country and citizenship. Even Saint Nino, founder of the Georgian Church, came from Kapadokia. Saint of Georgian Church, martyr Razhden, and Saint Evstati Mtskheteli were Persian. Famous 12 fathers struggling against fire-worship and Monophysitism were Assyrian (Syrian). Neopyth Urbani Episcope was Arabian. The famous Saint Abo Tbileli came from Arabia too. The Saint Queen Shushanik was Armenian etc. The above list shows that Georgian church unified all citizens of the country in spite of their ethnic origin. At the same time, the Georgian church always used to create a united cultural space. The Georgian Church was consolidating regions and different ethnic groups of Georgia. The Georgian language was the key factor of Georgian Christian culture. Initially, Georgian language and based on it Georgian Christian culture embraced whole Georgia, all its regions. Divine services, all church acts, in mountains and lowlands from the Black Sea to Armenia and Albania were implemented only in Georgian language. Georgian language and Georgian culture dominated all over the Georgian territory. And just this differentiates old Georgia from the present one. It’s evident that the main flocks of Georgian Church were Georgians of West, South and East Georgia. -

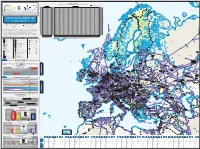

System Development Map 2019 / 2020 Presents Existing Infrastructure & Capacity from the Perspective of the Year 2020

7125/1-1 7124/3-1 SNØHVIT ASKELADD ALBATROSS 7122/6-1 7125/4-1 ALBATROSS S ASKELADD W GOLIAT 7128/4-1 Novaya Import & Transmission Capacity Zemlya 17 December 2020 (GWh/d) ALKE JAN MAYEN (Values submitted by TSO from Transparency Platform-the lowest value between the values submitted by cross border TSOs) Key DEg market area GASPOOL Den market area Net Connect Germany Barents Sea Import Capacities Cross-Border Capacities Hammerfest AZ DZ LNG LY NO RU TR AT BE BG CH CZ DEg DEn DK EE ES FI FR GR HR HU IE IT LT LU LV MD MK NL PL PT RO RS RU SE SI SK SM TR UA UK AT 0 AT 350 194 1.570 2.114 AT KILDIN N BE 477 488 965 BE 131 189 270 1.437 652 2.679 BE BG 577 577 BG 65 806 21 892 BG CH 0 CH 349 258 444 1.051 CH Pechora Sea CZ 0 CZ 2.306 400 2.706 CZ MURMAN DEg 511 2.973 3.484 DEg 129 335 34 330 932 1.760 DEg DEn 729 729 DEn 390 268 164 896 593 4 1.116 3.431 DEn MURMANSK DK 0 DK 101 23 124 DK GULYAYEV N PESCHANO-OZER EE 27 27 EE 10 168 10 EE PIRAZLOM Kolguyev POMOR ES 732 1.911 2.642 ES 165 80 245 ES Island Murmansk FI 220 220 FI 40 - FI FR 809 590 1.399 FR 850 100 609 224 1.783 FR GR 350 205 49 604 GR 118 118 GR BELUZEY HR 77 77 HR 77 54 131 HR Pomoriy SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT MAP HU 517 517 HU 153 49 50 129 517 381 HU Strait IE 0 IE 385 385 IE Kanin Peninsula IT 1.138 601 420 2.159 IT 1.150 640 291 22 2.103 IT TO TO LT 122 325 447 LT 65 65 LT 2019 / 2020 LU 0 LU 49 24 73 LU Kola Peninsula LV 63 63 LV 68 68 LV MD 0 MD 16 16 MD AASTA HANSTEEN Kandalaksha Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 MK 0 MK 20 20 MK 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM NL 418 963 1.381 NL 393 348 245 168 1.154 NL T +32 2 894 51 00 T +32 2 209 05 00 PL 158 1.336 1.494 PL 28 234 262 PL Twitter @ENTSOG Twitter @GIEBrussels PT 200 200 PT 144 144 PT [email protected] [email protected] RO 1.114 RO 148 77 RO www.entsog.eu www.gie.eu 1.114 225 RS 0 RS 174 142 316 RS The System Development Map 2019 / 2020 presents existing infrastructure & capacity from the perspective of the year 2020. -

The Security of the Caspian Sea Region

17. The glitter and poverty of Chechen Islam Aleksei Malashenko I. Introduction Originally the separatist movement in Chechnya was unrelated to Islam. Its ideology was ethnic nationalism and its goal was the establishment of an inde- pendent national state. The Chechen separatists’ social base was limited: far from all members of Chechen society supported the idea of independence. Nor, it seems, did the leaders of the Chechen insurgents seriously believe that it was possible for Chechnya to attain true independence. The future president of the self-proclaimed Chechen Republic of Ichkeriya, Soviet Air Force Major- General Dzhokhar Dudayev, used to say that after Chechnya gained inde- pendence it would join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and preserve its close economic and political ties with Russia. Before the beginning of the armed struggle for independence the Chechens aimed at maximum autonomy within the Russian Federation. The strategic tasks which the Chechen leaders set themselves were largely similar to those pursued, and realized for a period of time, by the ethno-political elite of Tatar- stan.1 In Chechnya, for a number of reasons (which are not the subject of the present study), the conflict between the centre and Grozny followed a different path—that of military–political confrontation, in which Islam became one of the main ideological and political vectors. In the Russian scholarly literature and other publications much has been written about the important role of Islam in the events of the 1990s in Chechnya. The more convincing work is that of Vakhid Akaev (a Chechen researcher),2 Alexei Kudryavtsev and Vladimir Bobrovnikov (two orientalists based in Moscow), and the journalist experts Ilya Maksakov and Igor Rotar.3 1 In 1993 only 2 republics—Tatarstan and Chechnya—refused to sign the Federation Treaty. -

Effects of Torture Among Chechen Refugees in Norway

Effects of torture among Chechen refugees in Norway Report by Amnesty International Danish Medical Group 2006 Effects of torture among Chechen refugees in Norway REPORT BY AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL DANISH MEDICAL GROUP 2006 THE DOCTORS BEHIND THE REPORT ARE: Tania Nicole Masmas MD Claes Kjær MD Lise Worm MD Morten Ekstrøm MD © Amnesty International, Danish section Quoting the text is permitted when mentioning Amnesty International as the source GRAPHIC DESIGN OG PHOTO: Michala Clante Bendixen PRINT: Scanprint, November 2006 ISBN: 87-88252-16-7 Amnesty International Gammeltorv 8, 5. sal DK-1457 København K Denmark e-mail: [email protected] www.amnesty.dk CONTENTS Introduction 5 Ethical Aspects 6 Material 6 Methods 6 Results 6 Medical examination 8 Discussion 8 Conclusion 9 Table 1: Background characteristics of Chechen examinees 10 Table II: Interview chart 11 Table III: Circumstances surrounding arrest and imprisonment 12 Table IV: Types of torture and other cruel inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment 14 Table V: Physical and psychological symptoms 15 Table VI: Physical findings of objective examination 16 Table VII: Anatomical distribution of all scars 16 Photos 17 Cases 18 References 25 Northern Caucasus and Georgia GIMU / PGDS Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of March 2004 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected] Shpakovskoye Termirgoyevskaya Blagodarnoyy R Novokubansk O W . StavropoStavropolll C StavropoStavropolll L 3 A _ A I G R O E Kurganinsk G Giaginskaya S Kalinovskoye U S A Levokumskoye C -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 374 International Conference on Man-Power-Law-Governance: Interdisciplinary Approaches (MPLG-IA 2019) Figurative structure of the Avar proverbs Magomed Magomedov Suleihat Mallaeva Zainab Omarova Doctor of Philology, Professor, Chief Doctor of Philology, Professor, Chief Candidate of Philological Sciences, Researcher at the G. Tsadasa Researcher at the G. Tsadasa Associate Professor, Dean of the Institute of Language, Literature and Institute of Language, Literature and Faculty of Dagestan Philology Art Art Dagestan State Pedagogical Dagestan Scientific Center of the Dagestan Scientific Center of the University Russian Academy of Sciences Russian Academy of Sciences Makhachkala, Russia Makhachkala, Russia Makhachkala, Russia Daniyal Magomedov Scientist G. Tsadasa Institute of Language, Literature and Art Dagestan Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences Makhachkala, Russia [email protected] Abstract–The article considers the artistic means used feature of a separate idiom, didactic meaning can be in the Avar language for the enhancing of the considered to be their integral characteristics [1]. S.I. expressiveness of proverbs: brevity, rhythm, alliteration, Ozhegov characterizes a proverb as a short folk rhyme, paired use of words, parallelism. Brevity is aphorism with didactic meaning; a folk aphorism [2]. characterized as the most important stylistic law of the proverb which gives it nativeness and distinguishes it Wide use of special stylistic means promotes from the maxim which is a literary version of the proverb. expressive function of proverbs. These means are: Imagery is also inherent in the Avar paremia, although it brevity, figurativeness, rhythm, rhyme, parallelism. is not obligatory. Imaginative transfer can be both metonymic and metaphorical. -

List of English and Native Language Names

LIST OF ENGLISH AND NATIVE LANGUAGE NAMES ALBANIA ALGERIA (continued) Name in English Native language name Name in English Native language name University of Arts Universiteti i Arteve Abdelhamid Mehri University Université Abdelhamid Mehri University of New York at Universiteti i New York-ut në of Constantine 2 Constantine 2 Tirana Tiranë Abdellah Arbaoui National Ecole nationale supérieure Aldent University Universiteti Aldent School of Hydraulic d’Hydraulique Abdellah Arbaoui Aleksandër Moisiu University Universiteti Aleksandër Moisiu i Engineering of Durres Durrësit Abderahmane Mira University Université Abderrahmane Mira de Aleksandër Xhuvani University Universiteti i Elbasanit of Béjaïa Béjaïa of Elbasan Aleksandër Xhuvani Abou Elkacem Sa^adallah Université Abou Elkacem ^ ’ Agricultural University of Universiteti Bujqësor i Tiranës University of Algiers 2 Saadallah d Alger 2 Tirana Advanced School of Commerce Ecole supérieure de Commerce Epoka University Universiteti Epoka Ahmed Ben Bella University of Université Ahmed Ben Bella ’ European University in Tirana Universiteti Europian i Tiranës Oran 1 d Oran 1 “Luigj Gurakuqi” University of Universiteti i Shkodrës ‘Luigj Ahmed Ben Yahia El Centre Universitaire Ahmed Ben Shkodra Gurakuqi’ Wancharissi University Centre Yahia El Wancharissi de of Tissemsilt Tissemsilt Tirana University of Sport Universiteti i Sporteve të Tiranës Ahmed Draya University of Université Ahmed Draïa d’Adrar University of Tirana Universiteti i Tiranës Adrar University of Vlora ‘Ismail Universiteti i Vlorës ‘Ismail -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1 Overview ................................................................................................................................................ 9 1.1 Version Comparison ....................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................17 2 System Architecture ..............................................................................................................................18 2.1 Controller Selection .......................................................................................................................19 3 Installation .............................................................................................................................................21 3.1 Standalone .....................................................................................................................................21 3.1.1 Windows PC Host .................................................................................................................21 3.2 Homeseer .......................................................................................................................................22 3.3 Registration ....................................................................................................................................23 3.3.1 Standalone .............................................................................................................................23 -

Victor Shnirelman

FOSTERED P RIMORDIALISM FFOSTEREDPPRIMORDIALISM:: TTHE IIDENTITY ANDAANCESTRYOF THE NN ORTH CC AUCASIAN TT URKS IN THE SS OVIET AND PP OST-S-SOVIET MM ILIEU Victor Shnirelman INTRODUCTION This paper focuses on the crucial issue in the continuing disagreement between modernists and traditionalists as to wheth- er it is correct to emphasize the “invention of tradition” and so- cial engineering in respect to nationalism, or whether one has to pay more attention to the cultural background of the emerging nationalist discourse. I will restrict my discussion to questions concerning the politics of the past, the contribution of which to the development of nationalism is difficult to overstate:1 Why is it that the most remote past and ethnic roots are mostly appre- ciated by many ethnic nationalists? What was there at the very beginning which makes them dig so tirelessly into the past? Why do some views of the past seem to be more persuasive than oth- ers, and under what conditions? Is it possible to appropriate the past of an alien community? Why do people apply to the past at all, particularly if a historical continuity has been broken? While discussing all these issues, I will test the well-known theories of Ernest Gellner,2 Eric Hobsbawm3 and Benedict Anderson4 on 1 Philip Kohl, Clare Fawcett, eds., Nationalism, Politics and the Practice of Archaeology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Phil- ip L. Kohl, “Nationalism and Archaeology: On the Constructions of Nations and the Reconstructions of the Remote Past,” Annual Review of Anthropology 27 (1998), pp. 223-246; Margarita Diaz-Andreu, Timo- thy C.