Pulmonary Tb Among Myanmar Migrants in Samut Sakhon Province, Thailand: a Problem Or Not for the Tb Control Program?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation Due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No

(Unofficial Translation) Order of the Centre for the Administration of the Situation due to the Outbreak of the Communicable Disease Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) No. 1/2564 Re : COVID-19 Zoning Areas Categorised as Maximum COVID-19 Control Zones based on Regulations Issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005) ------------------------------------ Pursuant to the Declaration of an Emergency Situation in all areas of the Kingdom of Thailand as from 26 March B.E. 2563 (2020) and the subsequent 8th extension of the duration of the enforcement of the Declaration of an Emergency Situation until 15 January B.E. 2564 (2021); In order to efficiently manage and prepare the prevention of a new wave of outbreak of the communicable disease Coronavirus 2019 in accordance with guidelines for the COVID-19 zoning based on Regulations issued under Section 9 of the Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations B.E. 2548 (2005), by virtue of Clause 4 (2) of the Order of the Prime Minister No. 4/2563 on the Appointment of Supervisors, Chief Officials and Competent Officials Responsible for Remedying the Emergency Situation, issued on 25 March B.E. 2563 (2020), and its amendments, the Prime Minister, in the capacity of the Director of the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration, with the advice of the Emergency Operation Center for Medical and Public Health Issues and the Centre for COVID-19 Situation Administration of the Ministry of Interior, hereby orders Chief Officials responsible for remedying the emergency situation and competent officials to carry out functions in accordance with the measures under the Regulations, for the COVID-19 zoning areas categorised as maximum control zones according to the list of Provinces attached to this Order. -

The Technical Cooperation Project on Local Management Cooperation in Thailand

TERMINAL EVALUATION REPORT ON THE TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT ON LOCAL MANAGEMENT COOPERATION IN THAILAND FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT SEPTEMBER 2004 JICA Thailand Office TIO JR 04-017 KOKUSAI KOGYO (THAILAND) CO., LTD. TERMINAL EVALUATION REPORT ON THE TECHNICAL COOPERATION PROJECT ON LOCAL MANAGEMENT COOPERATION IN THAILAND FINAL REPORT MAIN REPORT SEPTEMBER 2004 JICA Thailand Office TIO JR 04-017 KOKUSAI KOGYO (THAILAND) CO., LTD. Terminal Evaluation Study for JICA Technical DLA-JICA Thailand Office Cooperation Project on Local Management Cooperation Color Plates Buri Ram Ayutthaya Songkhla Map of Thailand and Provinces at Workshop Sites i Terminal Evaluation Study for JICA Technical DLA-JICA Thailand Office Cooperation Project on Local Management Cooperation Color Plates 1 Courtesy visit to Ayutthaya Governor. 2 Visiting Arunyik Village, the most famous place for sword maker, in Ayutthaya province. The local authorities planned to cooperate for tourism promotion. 3 General condition at disposal site of Nakhon Luang Sub-district Municipality. 4 Visiting Silk factory in Buri Ram. The local authority planned to promote tourism for local cooperation. 5 Visiting homestay tourism in Buri Ram. 6 Local cooperation activity, tree plantation, in Buri Ram. 7 Closing workshop for the project. ii CONTENTS OF EVALUATION REPORT Page Location Map i Color Plates ii Abbreviations vi Chapter 1 Outline of Evaluation Study Z1-1 1.1 Objectives of Evaluation Study Z1-1 1.2 Members of Evaluation Study Team Z1-1 1.3 Period of Evaluation Study Z1-1 1.4 Methodology of Evaluation Study Z1-1 Chapter 2 Outline of Evaluation Project Z2-1 2.1 Background of Project Z2-1 2.2 Summary of Initial Plan of Project Z2-1 Chapter 3 Achievement of Project Z3-1 3.1 Implementation Framework of Project Z3-1 3.1.1 Project Purpose Z3-1 3.1.2 Overall Goal Z3-1 3.2 Achievement in Terms of Output Z3-2 3.3 Achievement in Terms of Activity Z3-2 3.4 Achievement in Terms of Input Z3-3 3.4.1 Japanese side Z3-3 a. -

Final Project Report English Pdf 463.15 KB

CEPF Final Project Completion Report Organization Legal Name Bird Conservation Society of Thailand Project Title Building a Network for Monitoring Important Bird Areas in Thailand CEPF GEM No. CEPF-032-2014 Date of Report Report Author Thattaya Bidayabha 221 Moo 2 Soi Ngamwongwan 27 Ngamwongwan Road, Bangkhen, Muang, Nonthaburi 11000 Thailand Author Contact Information Tel.: +66 2 588 2277 Fax: +66 2 588 2277 E-mail: [email protected] CEPF Region: Indo-Burma Strategic Direction: Strategic Direction 8: "Strengthen the capacity of civil society to work on biodiversity, communities and livelihoods at regional, national, local and grassroots levels" Grant Amount: $19,999 Project Dates: November 1st, 2014 to October 31st, 2015 1. Implementation Partners for this Project Department of National Parks, Wildlife, and Plant Conservation - the government agency that is responsible for the management of and law enforcement in protected areas. Universities - Kasetsart University, Chiang Mai University, Khon Kaen University, and Walailuck University hosted the IBA monitoring workshops. Local Conservation Clubs; - Khok Kham Conservation Club, Khok Kham district, Samut Sakhon province. They were involved in IBA monitoring in the Inner Gulf of Thailand - Lanna Bird Club, Chiang Mai province. They were involved in IBA monitoring in northern Thailand. - Nan Birding Club, Nan province. They were involved in IBA monitoring in northern Thailand. - Mae Moh Bird Conservation Club, Lampang province. They were involved in IBA monitoring in northern Thailand. - Chun Conservation Club, Phayao province. They were involved in IBA monitoring in northern Thailand. - Flyway Foundation, Chumphon province. They were involved in IBA monitoring in southern Thailand. - Khao Luang Bird Conservation Club, Nakhon Sri Thammarat province. -

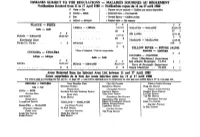

CHOLERA T — CHOLÉRA T Africa — Afrique

Wkly Epidern. Rec.: No. 38 - 19 Sept. 1980 296 — Relevé epidém. hebd,; N° 38 - 19 sept. 1980 PORTS DESIGNATED IN APPLICATION PORTS NOTIFIÉS EN APPLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL HEALTH REGULATIONS DU RÈGLEMENT SANITAIRE INTERNATIONAL Amendments to 1979 publication Amendements à la publication de 1979 D EX Insert — Insérer: Australia — Australie B ro o m e........................................... X Camavon ................................... X Port W alcot............................... X Turkey — Turquie M e r s in ......................................................... X S arm iin ....................... ' . X Trabzon ..... ................................ X United Kingdom — Royaume-Uni Ip sw ich ......................................................... N X (From 1 October 1980 — Dès le 1er octobre 1980) DISEASES SUBJECT TO THE REGULATIONS — MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 11 to 18 September 1980 — Notifications reçues du 11 an 18 septembre 1980 C Cases — Cas ... Figures not yet received — Chiffres aon encore disponibles D Deaths — Diets i Imported cases — Cas importés P Port r Revised figures — Chiffres révisés A Airport — Aéroport s Suspect cases — Cas suspects PLAGUE — PESTE C D C D America — Amérique MOZAMBIQUE ( contd — suite J 2 7 .v n -2 .v m INDIA — INDE 1 7 -2 3 .V U 1 134 1 C D 10 2 1 0 -1 6 .V U 1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 1.K ÉTATS-UNIS D’AMÉRIQUE TANZANIA, UNITED REP. OF 3 1 .v m -6 .ix 160 2 TANZANIE, REP.-UNIE DE New Mexico State 3 t9 .V 3 U Santa Fe County . , . l 1 0 30 2 114 2 24-30.VHI 24-30. vm SINGAPORE — SINGAPOUR 3I.VHI-6IX New Mexico State 95 10 1 0 Rio Arriba County . l 1 1 THAILAND — THAÏLANDE 2 4 - 3 0 . -

MALADIES SOUMISES AU RÈGLEMENT Notifications Received from 11 to 17 April 1980 — Notifications Reçues Dn 11 Au 17 Avril 1980 C Cases — C As

Wkly Epidem. Rec * No. 16 - 18 April 1980 — 118 — Relevé èpidém, hebd. * N° 16 - 18 avril 1980 investigate neonates who had normal eyes. At the last meeting in lement des yeux. La séné de cas étudiés a donc été triée sur le volet December 1979, it was decided that, as the investigation and follow et aucun effort n’a été fait, dans un stade initial, pour examiner les up system has worked well during 1979, a preliminary incidence nouveau-nés dont les yeux ne présentaient aucune anomalie. A la figure of the Eastern District of Glasgow might be released as soon dernière réunion, au mois de décembre 1979, il a été décidé que le as all 1979 cases had been examined, with a view to helping others système d’enquête et de visites de contrôle ultérieures ayant bien to see the problem in perspective, it was, of course, realized that fonctionné durant l’année 1979, il serait peut-être possible de the Eastern District of Glasgow might not be representative of the communiquer un chiffre préliminaire sur l’incidence de la maladie city, or the country as a whole and that further continuing work dans le quartier est de Glasgow dès que tous les cas notifiés en 1979 might be necessary to establish a long-term and overall incidence auraient été examinés, ce qui aiderait à bien situer le problème. On figure. avait bien entendu conscience que le quartier est de Glasgow n ’est peut-être pas représentatif de la ville, ou de l’ensemble du pays et qu’il pourrait être nécessaire de poursuivre les travaux pour établir le chiffre global et à long terme de l’incidence de ces infections. -

List of Ports for Foreign Fishing Vessels and Aquatic Animals Transporting Vessels 1 Annexed to CCCIF Notification No

List of Ports for Foreign Fishing Vessels and Aquatic Animals Transporting Vessels 1 Annexed to CCCIF Notification No. 4/2558 Port Location Bangkok 1. Port of Bangkok Tha Rua Road, Khlong Toei District, Bangkok 2. Port No. 27, Krung Thai Rat Burana Road, Rat Burana Subdistrict, Rat Burana Warehouse District, Bangkok 3. Port No. 27 A, Rat Burana Rat Burana Road, Rat Burana Subdistrict, Rat Burana Warehouse District, Bangkok 4. Port No. 33 Rat Burana Road, Rat Burana Subdistrict, Rat Burana District, Bangkok Samut Prakarn Province 1. BMTP Port Suk Sawat Road, Pak Khlong Bang Pla Kot Subdistrict, Phra Samut Chedi District, Samut Prakarn Province 2. BDS Terminal Port Suk Sawat Road, Bang Chak Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 3. Saha Thai Port Puchao Saming Phray Road, Bang Ya Phraek Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 4. PorThor.10 Port Puchao Saming Phray Road, Sam Rong Tai Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 5. Phra Pradaeng Port Sam Rong Tai Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 6. Port No. 23 Pet-hueng Road, Bang Yo Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 7. Sub Staporn Port No. 21 B Pet-hueng Road, Bang Yo Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 8. Port No. 21 D Pet-hueng Road, Bang Yo Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 9. Nanapan Enterprise Port No. 21 A Pet-hueng Road, Bang Yo Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province 10. Raj Pracha Port No. 11 A Suk Sawat Road, Bang Chak Subdistrict, Phra Pradaeng District, Samut Prakarn Province Chonburi Province 1. -

Trace Elements in Marine Sediment and Organisms in the Gulf of Thailand

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Trace Elements in Marine Sediment and Organisms in the Gulf of Thailand Suwalee Worakhunpiset Department of Social and Environmental Medicine, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, 420/6 Ratchavithi Rd, Bangkok 10400, Thailand; [email protected]; Tel.: +66-2-354-9100 Received: 13 March 2018; Accepted: 13 April 2018; Published: 20 April 2018 Abstract: This review summarizes the findings from studies of trace element levels in marine sediment and organisms in the Gulf of Thailand. Spatial and temporal variations in trace element concentrations were observed. Although trace element contamination levels were low, the increased urbanization and agricultural and industrial activities may adversely affect ecosystems and human health. The periodic monitoring of marine environments is recommended in order to minimize human health risks from the consumption of contaminated marine organisms. Keywords: trace element; environment; pollution; sediment; gulf of Thailand 1. Introduction Environmental pollution is an urgent concern worldwide [1]. Pollutant contamination can exert adverse effects on ecosystems and human health [2]. Trace elements are one type of pollutant released into the environment, and metal contamination levels are rising. The main sources of trace elements are natural activities such as volcanic eruptions and soil erosion, and human activities such as industrial production, waste disposal, the discharge of contaminated wastewater, the inappropriate management of electronic waste (e-waste), and the application of fertilizers in agriculture [3–7]. Once trace elements are released into the environment, they can be dispersed by the wind and deposited in soil and bodies of water, accumulating in marine sediments [8,9]. -

2018 9,115 4,865 2016 2017 2018

ANNUAL REPORT CK POWER2 PUBLIC0 COMPANY1 LIMITED8 ENDL ES S E N E R G Y “We Produce Energy, Energy Powers Our Lives” As a result of endless energy needs, the way we deal with such challenges from an ongoing increase in demands to a higher living standard requires significant effort. CKP is fully committed to using our knowledge and innovations to deliver reliable energy to all and ensure a sustainable development for all communities. “Attention, Care, Revive and Rehabilitate” To achieve energy reliability and sustainable business growth in the future, we thus give priority to the efficient use of natural resources. We meticulously control every single part of our production process to minimize potential negative impacts to ensure that the business, earth, water, sky, forests and all living things can coexist and grow together in a sustainable manner. Vision To be a leading power business company in Thailand and the ASEAN region, with efficient operation. Mission 1) To generate an optimal, stable and fair return for shareholders. 2) To be responsible to the environment, community and all stakeholders. 06 Financial Highlight CONTENTS 08 Message from Chairman of the Board of Directors 10 Board of Directors PART Business Operations 16 Business Policy and Overview 25 Nature of Business Operations 42 Risk Factors 47 Legal Disputes 49 General Information and Other 1 Significant Information PART Management and Corporate Governance 54 Information on Securities and Shareholders of the Company 62 Management Structure 86 Corporate Governance 115 Corporate -

Nadee Pilot Project, Samut Sakhon Province, THAILAND

ASSESSMENT ON SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIAL WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR A CIRCULAR AND INCLUSIVE ECONOMY Nadee Pilot Project, Samut Sakhon Province, THAILAND Prepared by Ecological Alert and Recovery-Thailand (EARTH), Submitted to Strategy and Programme Management Division, UN-ESCAP, July 31th, 2020 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS AN OVERALL ASSESSMENT ON SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIAL WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR A CIRCULAR AND INCLUSIVE ECONOMY A. INTRODUCTION 3 B. MULTI-STAKEHOLDER WORKING GROUP 4 C. PLANNED OUTPUTS 5 D. ASSESSMENT AREAS 5 E. FINDINGS 6 F. FINDINGS ON GENDER EQUALITY AND PRO-POOR AS CROSS-CUTTING ISSUES 9 G. FINDINGS ON RELEVANT SURM-RELATED SDGs ALIGNMENT 10 STUDY ON MATERIAL FLOW ANALYSIS OF INDUSTRIAL WASTE MANAGEMENT IN NADEE CITY A. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY 20 B. METHODOLOGY 20 C. ASSESSMENT FINDINGS 20 D. CURRENT PRACTICES OF WASTE MANAGEMENT ACCORDING TO 3R PRINCIPLES BY 14 INTERVIEWED FOOD, BEVERAGES, COLD STORAGE AND TEXTILES INDUSTRIALS IN JULY 2020 23 E. KEY RECOMMENDATIONS 26 STUDY ON ANALYSIS OF INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITY AND NEEDS OF PRIVATE SECTOR AND GOVERNMENT AGENCIES IN INDUSTRIAL WASTE MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING FOR CIRCULAR ECONOMY IN NADEE CITY A. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY 29 B. METHODOLOGY 29 C. ASSESSMENT FINDINGS 30 D. Key recommendations 35 STUDY ON POLICY ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS TO NADEE SUB-DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY A. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY 38 B. METHODOLOGY 38 C. ASSESSMENT FINDINGS 39 D. REVIEW OF GOOD PRACTICES 41 E. KEY PRELIMINARY RECOMMENDATIONS TO NADEE MUNCIPALITY 43 F. KEY RECOMMENDATIONS TO NATIONAL GOVERNMENT AGENCIES 44 AND RELATED DEPARTMENTS APPENDICES 46 2 AN OVERALL ASSESSMENT ON SUSTAINABLE INDUSTRIAL WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR A CIRCULAR AND INCLUSIVE ECONOMY A. -

Revisiting the Pandemic: Surveys on the Impact of COVID-19 on Small Businesses and Workers THAILAND

Revisiting the Pandemic: Surveys on the Impact of COVID-19 on Small Businesses and Workers THAILAND THAILAND Revisiting the Pandemic: Surveys on the Impact of COVID-19 on Small Businesses and Workers Thailand Report Three Rounds of Surveys (May 2020 - January 2021) Nalitra Thaiprasert Supanika Leurcharasmee Matthew Chatsuwan Woraphon Yamaka Thomas Parks MAY 2021 Copyright © The Asia Foundation 2021 Table of contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 2 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3 IMPACT ON THE THAI WORKFORCE 11 IMPACT ON MICRO AND SMALL BUSINESSES 25 CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS 41 ANNEX 44 Acknowledgements The Asia Foundation gratefully acknowledges the contributions that many individuals, organizations, and funders have made in carrying out this study on the impact of COVID-19 on small businesses and workers, which covers six countries in Southeast Asia: Cambodia, the Lao Peoples’ Democratic Republic (Lao P.D.R.), Malaysia, Myanmar, Thailand, and Timor-Leste. In most cases, the Foundation collaborated with local partners in designing and carrying out the country surveys, conducting interviews for the case studies, and analyzing the data. For this report, which presents research we conducted in Thailand, the Foundation would like to thank our Thai partners: the School of Development Economics of the National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA), and the survey firm, MI Advisory (Thailand). We would also like to thank our research assistant, Nathapong Tuntichiranon, who helped us to analyze the data, and produced the excellent figures; Jirakom Sirisrisakulchai and Paravee Maneejuk from Chiang Mai University’s Faculty of Economics, who reviewed the econometric models; Athima Bhukdeewuth, who prepared the cover design and the layout; and our technical editor, Ann Bishop. -

SWG Thailand TIP Report 2021 Submission SWG Publication Final

Comments Concerning the Ranking of Thailand by the United States Department of State in the 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report Comments submitted by Global Labor Justice- International Labor Rights Forum on behalf of the Seafood Working Group March 31, 2021 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1. METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................................. 2 2. OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................................. 3 2.1. PROMINENT CASES OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND EGREGIOUS LABOR RIGHTS ABUSE ............................................... 3 2.2. POLICY FAILURES AND CHALLENGES .......................................................................................................... 4 3. PROTECTION ........................................................................................................................................... 6 3.1. EXAMPLES OF FAILURE TO PROTECT .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. Rohingya wrongly identified as “illegal aliens” ........................................................................................................ 6 3.1.2. Document confiscation, wage withholding, inability to change employer, physical violence -

Thailand to Prepare the Inputs and Contributions of the Royal Thai Government to Inform the Regional Preparatory Meeting to Be Held in Bangkok in November 2017

Cumulative Outcomes from the National Consultations on the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration Workshop I: Mae Sot 14 August 2017 • Workshop II: Samut Sakhon 17 October 2017 The Royal Thai Government • Ministry of Foreign Affairs • IOM FINAL REPORT - 1 November 2017 - CONTENTS 3 Section I Introduction to the Global Compact for Migration- Background, Aims and Objectives 4 Section II Background to the National Stakeholder Workshops 5 Section III Thematic Cluster #1: Human Rights of all Migrants, Social Inclusion, Cohesion, and all Forms Of Discrimination, including Racism, Xenophobia and Intolerance 7 Section IV Thematic cluster #3: Governance of migration in all its dimensions, including at borders, on transit, entry, return, readmission, integration and reintegration Section V 8 Thematic cluster #4: Contributions of migrants and diasporas to all dimensions of sustainable development, including remittances and portability of earned benefits 9 Section VI Thematic cluster #5: Smuggling of migrants, trafficking in persons and contemporary forms of slavery, including identification, protection and assistance to victims 11 Section VII Thematic cluster #6: Irregular migration and regular pathways, including decent work, labor mobility, recognition of skills and qualifications, and other relevant measures 2 | P a g e (I) INTRODUCTION TO THE GLOBAL COMPACT FOR MIGRATION BACKGROUND, AIMS AND OBJECTIVES In an era characterized by environmental uncertainty, human-made crises, overpopulation and globalized economies, increasing trends in global migration have resulted in the necessity for strengthened migration governance. The international framework of the Sustainable Development Goals has recognized the positive contribution of migration and has brought to the attention of world leaders the need for countries and regions to engage in collaborative efforts to resolve shortcomings, share best practices and promote positive change in the way migration is perceived, managed and understood across the globe.