Page 1 TRANSPORT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION COMMISSION

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

Denmark, Sweden & Norway

Spring Term 2020 – An Exploration of Scandinavia Denmark, Sweden & Norway Things you will do/see: • Super cool CASTLES • Amazing VIKING SHIPS • Majestic MOUNTAINS • Fabulous FJORD CRUISES • Incredibly scenic TRAIN JOURNEYS • The park that inspired Walt Disney! TRAVEL DATES: MAY 14-24, 2020 PROGRAM FEE: $3350 Sign up now to reserve your spot!! Initial Deposit Due Date: 11/1/19 (Space is limited, first come first served!) Included: • All Flights/transportation • Hotel Accomodation • Several meals, inc. daily breakfast • Admission to sites • Train, ferry and boat rides QUESTIONS? WANT TO SIGN UP? Dr. George Ricco - [email protected] UNIVERSITY OF INDIANAPOLIS SPRING TERM TRIP TO SCANDINAVIA: DENMARK, SWEDEN & NORWAY MAY 14-24, 2020 Faculty Trip Leader: Dr. George Ricco – Asst. Professor of Engineering TRIP INFORMATION: Travel Dates: May 14-May 24, 2020 Trip organized by: MAVtravel LLC Program Fee: $3350* (includes international flights, accommodation, transportation while abroad, admission to sites/visits on the itinerary, several meals, locals guides and tour director service) PLEASE NOTE: Affordable travel insurance is available at an additional cost – Please contact MAVtravel LLC for more information and rates Course requirements: TBD – Dr. Ricco will keep you posted *Fees are based on 26 student participants, double occupancy, and are subject to change due to currency fluctuations and/or fee changes made by our partner suppliers prior to contracts being confirmed. As such, MAVtravel LLC, reserves the right to adjust the program itinerary -

Zhong Tie Bo Hai 1 Hao

new delivery Zhong Tie Bo Hai 1 Hao Since the beginning of November, Ferry Co Ltd, the ships are designed to serve – three million tonnes allocated to Dalian and the first in a series of diesel- a new train ferry line across the Bohai Strait three and a half million tonnes to Yantai. electric train ferries delivered from between Yantai and Dalian. The new ferry is owned by a joint venture the Tianjin Xingang Shipyard in The newbuildings have been designed by between Sinorail (50 per cent), Dalian Tanggou has served a new route Shanghai Merchant Ship & Research Institute, Construction & Investment Co (17.5 per cent), together with the shipyard. Zhong Tie Bo Yantai Power Investment Co (17.5 per cent) and 95° 100° 105° 110 115 across120 the° Bohai 125Strait° between130 ° 135° Yantai in east China and Dalian in Hai 1 Hao is designed to carry freight train Sinorail No 2 Bureau Ltd (15 per cent). In 2004, l X a wagons, trucks, cars and passengers. It has an the cost of the total project was initially estimated yk I Blagoveshchensk a A B the northeast Khabarovsk z. O O overall length of 182.6m, breadth of 24.8m and T A m E G H ZHONG TIE BO HAI 1 HAO Irkutsk E B u r R N I H N a draft of 5.8m. K I G Y L G Y Builder Tianjin Xingang Shipyard V A Currently, more than 18 million tonnes of Hovsgol O N N N O A L Nuur Kyakhta L I N a Owner/operator Sinorail Bohai Train Ferry Co Ltd. -

Options for Changes to Revenue Support Freight Grant Schemes

Options for changes to Revenue Support Freight Grant Schemes FINAL REPORT Options for Changes to Revenue Support Freight Grant Schemes CONTENTS Page List of abbreviations 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background to the study 9 1.2 The existing MSRS (Intermodal) scheme 10 1.3 Key definitions 11 1.4 Structure of this report 12 2 MARKET ANALYSIS 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 GB-Continent unitload freight market 13 2.3 Unitload coastal shipping services 18 2.4 Conclusions on market analysis 20 3 GENERIC COST MODELS 3.1 Introduction 22 3.2 Channel Tunnel Cost Model 22 3.3 Coastal Shipping Cost Model 32 3.4 Conclusions on cost modelling 38 4 RESULTS OF STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION 4.1 Introduction 39 4.2 Results 40 5 STATE AID GUIDELINES 5.1 Introduction 46 5.2 Review of maritime State aid guidelines 46 5.3 Conclusion on state aids 49 6 CONCLUSIONS 6.1 Channel Tunnel intermodal rail freight 50 6.2 MSRS (Coastal Shipping) scheme 51 APPENDICES Appendix 1: GB-Continent ferry services (excluding Dover Straits) 53 Appendix 2: Coastwise LOLO services 55 Appendix 3: MSRS Coastal Shipping Model 57 Appendix 4: Quality assurance report on the MSRS Coastal 62 Shipping Model 1 Options for changes to Revenue Support Freight Grant Schemes List of abbreviations 3PL Third party logistics provider C&D Collection and delivery DfT Department for Transport EC European Commission EU European Union HGV Heavy Goods Vehicle LOLO Load-on Load Off MDST MDS Transmodal Ltd MGO Marine Gas Oil MSRS Modal Shift Revenue Support RORO Roll-on Roll-off SECA Sulphur Emission Control Area TEU Twenty foot equivalent unit WFG Waterborne Freight Grant 2 Options for changes to Revenue Support Freight Grant Schemes EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Chapter 1: Introduction The Department for Transport (DfT) has commissioned Atkins, and through Atkins MDS Transmodal (MDST), to consider options for changes to Revenue Support Freight Grant Schemes. -

Navigation Report on New Zealand King Salmon's

NAVIGATION REPORT ON NEW ZEALAND KING SALMON’S PROPOSAL FOR NEW SALMON FARMS IN THE MARLBOROUGH SOUNDS 29 SEPTEMBER 2011 BY DAVID WALKER CONTENTS PAGE NO. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION 3 Current Position 3 History of involvement in Marlborough Sounds 3 Aquaculture 3 Maritime education and training 4 Qualifications 4 Experience on large vessels 5 Key references 5 SCOPE OF REPORT 7 THE MARLBOROUGH SOUNDS FROM A NAVIGATION PERSPECTIVE: 8 Navigation 8 Electronic Navigation 9 Weather 11 Visibility 11 Fog 11 Tides 12 Marine farms 13 NAVIGATION IN QUEEN CHARLOTTE SOUND 13 NAVIGATION IN TORY CHANNEL 14 PELORUS SOUND 16 PORT GORE 17 NAVIGATION AND SALMON FARMS 19 Commercial vessels over 500 gross tonnage within the designated Pilotage Area 19 Commercial small boats 21 Recreational small boats 22 Collisions between vessels and marine farms 23 INTERACTIONS BETWEEN VESSELS AND MARINE FARMS 25 Beneficial effects of the farms on navigational safety 26 NAVIGATIONAL ISSUES RELATING TO THE PROPOSED SITES 26 Waitata Reach 26 Papatua 28 Ngamahau 30 Ruaomoko and Kaitapeha 33 CONDITIONS TO BE IMPOSED 36 Notification to Mariners/Education 36 Buoyage 37 Restricted visibility 37 Lighting 38 Engineering 39 AIS 40 Emergency procedures 41 Executive summary 1. This report was commissioned by The New Zealand NZ King Salmon Company Ltd (NZ King Salmon) and assesses the effects of NZ King Salmon’s proposal for nine new marine farm sites on navigation in the Marlborough Sounds. In summary, my view as an experienced navigator, both within the Marlborough Sounds and elsewhere, is that provided the farms operate under an appropriate set of conditions the farms will have the following effect on navigation: a. -

Penguin Self-Guided Walk

WCC024 Penguin cover.pART 11/23/05 10:26 AM Page 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composite PENGUIN SELF GUIDED WALK KARORI CEMETERY HERITAGE TRAIL Thiswalk takes about togo minutes to two hours. Markers direct you round the walk, all the paths are sign posted and the graves are marked with the Penguinwreck marker. The walk startsat the Hale memorial and finishes at the second Penguin memorial in the Roman Catholic section of the cemetery. The WellingtonOty Coundl gratefullyacknowledges the assistance of BruteE Colllns,author of The WTedrO/thePfnguln,Steell! Roberts, Wellington and of RogerSteeleofsteele Roberts. Historical research:Delrdre TWogan, Karorl HistoricalSociety Author. DeirdreTWogan Wellington CityCouncil is a memberof the HeritageTrails Foundation Brochuresfor other Coundl walksare availableat theVIsitor InformationonJce lm Wakefleld Street. You can also visit the WellingtonCity Coundl on-line at www.wellington.gavt.nz (overimage: Penguinleaving Wellington (Zak PhDlDgraph, Hocken LibrillY) Wellington City Council Introduction The wreck of the Penguin on 12 February 1909 with a death toll of 72 was the greatest New Zealand maritime disaster of the 20th century. The ship went down in Cook Strait, only a few kilometres from where the Wahine was wrecked in April 1968, with the loss of 51 lives. Built of iron in 1864, on its Glasgow-Liverpool run the Penguin was reputed to be one of the fastest and most reliable steamers working in the Irish Sea. At the time of the wreck she had served the Union Steam Ship Company for 25 years, most recently on the Lyttelton and Cook Strait run. The Risso’s dolphin known to thousands as Pelorus Jack cavorted round the Penguin’s bows in the early years of the century, but after a collision in 1904 kept its distance — until January 1909 when it suddenly reappeared. -

12 Schedules Schedules 12 Schedules

12 Schedules 12 Schedules 12 Schedules 12 Schedules contents Schedule Page number Schedule A: Outstanding water bodies A1-A3 279 Schedule B: Ngā Taonga Nui a Kiwa B 281 Schedule C: Sites with significant mana whenua values C1-C5 294 Schedule D: Statutory Acknowledgements D1-D2 304 Schedule E: Sites with significant historic heritage values E1-E5 333 Schedule F: Ecosystems and habitats with significant indigenous biodiversity values F1-F5 352 Schedule G: Principles to be applied when proposing and considering mitigation and G 407 offsetting in relation to biodiversity Schedule H: Contact recreation and Māori customary use H1-H2 410 Schedule I: Important trout fishery rivers and spawning waters I 413 Schedule J: Significant geological features in the coastal marine area J 415 Schedule K: Significant surf breaks K 418 Schedule L: Air quality L1-L2 420 Schedule M: Community drinking water supply abstraction points M1-M2 428 Schedule N: Stormwater management strategy N 431 Schedule O: Plantation forestry harvest plan O 433 Schedule P: Classifying and managing groundwater and surface water connectivity P 434 Schedule Q: Reasonable and efficient use criteria Q 436 Schedule R: Guideline for stepdown allocations R 438 Schedule S: Guideline for measuring and reporting of water takes S 439 Schedule T: Pumping test T 440 Schedule U:Trigger levels for river and stream mouth cutting U 442 PROPOSED NATURAL RESOURCES PLAN FOR THE WELLINGTON REGION (31.07.2015) 278 Schedule A: Outstanding water bodies Schedule A1: Rivers with outstanding indigenous ecosystem -

Overseas Rail-Marine Bibliography

Filename: Dell/T43/bibovrmi.wpd Version: March 29, 2006 OVERSEAS RAIL-MARINE BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by John Teichmoeller With Assistance from: Ross McLeod, Phil Sims, Bob Parkinson, and Paul Lipiarski, editorial consultants. Introduction This installment is the next-to-last in our series of regional bibliographies that have covered the Great Lakes (Transfer No. 9), East Coast (Transfer No. 10 and 11), Rivers and Gulf (Transfer No. 18), Golden State [California] (Transfer No. 27) and Pacific Northwest (Transfer No. 36). The final installment, “Miscellaneous,” will be included with Transfer No. 44. It was originally our intention to begin the cycle again, reissuing and substantially upgrading the bibliographies with the additional material that has come to light. However, time and spent energy have taken their toll, so future updates will have to be in some other form, perhaps through the RMIG website. Given the global scope of this installment, I have the feeling that this is the least comprehensive of any sections compiled so far, especially with regard to global developments in the last thirty years. I have to believe there is a much more extensive literature, even in English, of rail-marine material overseas than is presented here. Knowing the “train ferry” (as they are called outside of North America) operations in Europe, Asia and South America, there must be an extensive body of non-English literature about these of which I am ignorant. However, as always, we publish what we have. Special thanks goes to Bob Parkinson for combing 80+ years of English technical journals. Moreover, I have included some entries here that may describe auto ferries and not car ferries, but since I have not seen some of the articles I am unsure; I have shared Bob’s judgements in places. -

Filing Port Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Next

Filing Port Call Sign Next Foreign Trade Official Vessel Type Total Dock Code Filing Port Name Manifest Number Filing Date Next Domestic Port Vessel Name Next Foreign Port Name Number IMO Number Country Code Number Agent Name Vessel Flag Code Operator Name Crew Owner Name Draft Tonnage Dock Name InTrans 4101 CLEVELAND, OH 4101-2021-00080 12/10/2020 - NACC CAPRI PORT COLBORNE, ONT - 9795244 CA 1 - WORLD SHIPPING, INC. MT 330 NOVAALGOMA CARRIERS SA 14 NACC CAPRI LTD 11'4" 0 LAFARGE CEMENT CORP., CLEVELAND TERMINAL WHARF N 5204 WEST PALM BEACH, FL 5204-2021-00248 12/10/2020 - TROPIC GEM PROVIDENCIALES J8QY2 9809930 TC 3 401067 TROPICAL SHIPPING CO. VC 310 TROPICAL SHIPPING COMPANY LTD. 13 TROPICAL SHIPPING COMPANY LTD. 11'6" 1140 PORT OF PALM BEACH BERTH NO. 7 (2012) DL 0102 BANGOR, ME 0102-2021-00016 12/10/2020 - LADY MARGARET FRMLY. ISLAND SPIRIT VERACRUZ 3FEO8 9499424 MX 2 44562-13 New England Shipping Co., Inc. PA 229 RAINBOW MARITIME CO., LTD. 19 GLOBAL QUARTZ S.A. 32'4" 10395 - - 1703 SAVANNAH, GA 1703-2021-00484 12/10/2020 SFI, SOUTHHAMPTON, UK NYK NEBULA - 3ENG6 9337640 - 6 33360-08-B NORTON LILLY PA 310 MTO MARITIME, S.A. 25 MTO MARITIME, S.A. 31'5" 23203 GARDEN CITY TERMINALS, BERTHS CB 1 - 5 D 4601 NEW YORK/NEWARK AREA 4601-2021-00775 12/10/2020 BALTIMORE, MD MSC Madeleine - 3DFR7 9305702 - 6 31866-06-A NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL PA 310 MSC MEDITERRANEAN SHIPPING COMPANY 21 COMPANIA NAVIEERA MADELEINE, PANAMA 42'7" 56046 NYCT #2 AND #3 DFL 4601 NEW YORK/NEWARK AREA 4601-2021-00774 12/10/2020 - SUNBELT SPIRIT TOYOHASHI V7DK4 9233246 JP 1 1657 NORTON LILLY INTERNATIONAL MH 325 GREAT AMERICAN LINES, INC. -

Are You Interested in Native Plants and Animals? Have Your Say on Our

Are you interested in native plants and animals? Have your say on Our Natural Capital InterestedWellington’s Draftin your Biodiversity local park? Strategy and Action Plan 2014 Consultation closed Friday 6 March 2015 51 submissions recieved No. Name Suburb Organisation Submission Source Page Number 1 allan probert wilton Online 1 2 Bronwen Shepherd Thorndon Online 4 3 Simon Adams Melrose Online 7 4 Suze Keith Kelburn Online 10 Makara Peak Mountain Bike 5 Jamie Stewart Karori Online Park Supporters Inc. 13 6 Jessi Morgan Courtenay Place Morgan Foundation Online 25 7 Wilbur Dovey Wilton Otari Wilton's Bush Trust Online 29 8 Bob Stephens Email 32 9 Paul Ward Newtown Online 38 10 Bill Hester Ngaio Email 44 11 Peter Henderson Khandallah Online 47 Creswick Valley Residents 12 Jennifer Boshier Northland Email Association 50 Greater Wellington Regional 13 Ali Caddy Email Council 56 14 Marc Slade Brooklyn Polhill Restoration Project Online 64 Wellington Mountain Bike 15 Russel Garlick Miramar Online Club Incorporated. 67 Friends of Taputeranga Marine 16 Murray Hosking Epuni Online Reserve Trust 71 17 Raewyn Empson Zealandia Email 78 18 Des Smith Ngaio Bell's track working group Online 82 Wellington Branch of Birds 19 Geoffrey de Lisle RD1 New Zealand (Ornithological Online Society of New Zealand) 85 20 Bev Abbott Wellington Botanical Society Email 90 21 Carol Comber Mt Cook Mobilised Email 117 22 Garth Baker Highbury Brooklyn Trail Builders Email 120 23 Alex James Hokowhitu Online 128 24 Craig Starnes Brooklyn Online 132 Aro Valley Restoration -

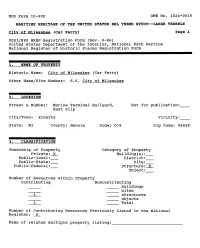

Car Ferry) Page 1 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev

NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 MARITIME HERITAGE OF THE UNITED STATES NHL THEME STUDY—LARGE VESSELS City of Milwaukee (Car Ferry) Page 1 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: City of Milwaukee (Car Ferry) Other Name/Site Number: S.S. City of Milwaukee 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Marine Terminal Railyard, Not for publication: East Slip City/Town: Elberta Vicinity: State: MI County: Benzie Code: 019 Zip Code: 49628 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s):__ Public-local: District: Public-State: Site: Public-Federal:__ Structure; X Obj ect:__ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ____ ____ buildings ____ ____ sites 1 ____ structures ____ ____ objects 1 ____ Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of related multiple property listing:_____________________ NFS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 City of Milwaukee (Car Perry) Page 2 USDI\NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

The Last Interglacial Sea-Level Record of Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa)

The last interglacial sea-level record of Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa) Deirdre D. Ryan1*, Alastair J.H. Clement2, Nathan R. Jankowski3,4, Paolo Stocchi5 1MARUM – Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany 5 2School of Agriculture and Environment, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand 3 Centre for Archeological Science, School of Earth, Atmospheric and Life Sciences, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia 4Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia 10 5NIOZ, Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, Coastal Systems Department, and Utrecht University, PO Box 59 1790 AB Den Burg (Texel), The Netherlands Correspondence to: Deirdre D. Ryan ([email protected]) Abstract: This paper presents the current state-of-knowledge of the Aotearoa New Zealand (Aotearoa) last interglacial (MIS 5 sensu lato) sea-level record compiled within the framework of the World Atlas of Last Interglacial Shorelines (WALIS) 15 database. Seventy-seven total relative sea-level (RSL) indicators (direct, marine-, and terrestrial-limiting points), commonly in association with marine terraces, were identified from over 120 studies reviewed. Extensive coastal deformation around New Zealand has prompted research focused on active tectonics, which requires less precision than sea-level reconstruction. The range of last interglacial paleo-shoreline elevations are resulted in a significant range of elevation measurements on both the North Island (276.8 ± 10.0 to -94.2 ± 10.6 m amsl) and South Island (173.1165.8 ± 2.0 to -70.0 ± 10.3 m amsl) and 20 prompted the use of RSL indicators tohave been used to estimate rates of vertical land movement; however, indicators in many instances lackk adequate description and age constraint for high-quality RSL indicators.