ALBANIAN 50P . Ll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bashkia F I E R Fondacioni Kulturor “H a R P A” Panairi Kombëtar I Librit “F I E R I 2 0 1 5” Programi I Aktivitete

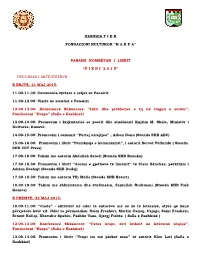

BASHKIA F I E R FONDACIONI KULTUROR “H A R P A” PANAIRI KOMBËTAR I LIBRIT “F I E R I 2 0 1 5” PROGRAMI I AKTIVITETEVE: E ENJTE, 21 MAJ 2015: 11.00-11.30: Ceremonia zyrtare e çeljes së Panairit 11.30-12.00: Vizitë ne stendat e Panairit 12.00-13.00: Konferencë Shkencore: “Libri dhe problemet e tij në tregun e sotëm”, Fondacioni „‟Harpa‟‟ (Salla e Bashkisë) 13.00-14.00: Promovim i krijimtarise se poetit dhe studiuesit Kujtim M. Shala, Ministër i Kulturës, Kosovë. 14.00-15.00: Promovim i romanit „‟Përtej urrejtjes‟‟ , Arben Dano (Stenda SHB ABC) 15.00-16.00: Promovim i librit “Përmbysja e komunizmit”, i autorit Servet Pëllumbi ( Stenda SHB UET Press) 17.00-18.00: Takim me autorin Abdullah Zeneli (Stenda SHB Buzuku) 17.30-18.30: Promovim i librit „‟Aroma e gjetheve të limonit‟‟ të Clara Sánchez, përkthim i Adrian Beshajt (Stenda SHB Dudaj) 17.30-18.30: Takim me autorin Ylli Molla (Stenda SHB Botart) 18.30-19.30: Takim me shkrimtarin dhe studiuesin, Zejnullah Rrahmani (Stenda SHB Faik Konica) E PREMTE, 22 MAJ 2015: 10.00-11.00: “Caste” - aktivitet në nder të autorëve më në zë të letërsisë, atyre që kanë përvjetore këtë vit. Ndër ta përmendim: Naim Frashëri, Martin Camaj, Cajupi, Sami Frashëri, Ernest Koliqi, Xhevahir Spahiu, Pashko Vasa, Gjergj Fishta ( Salla e Bashkisë ) 12.00-13.00: Konferencë Shkencore: “Fatos Arapi, zëri brilant në letërsinë shqipe”, Fondacioni „‟Harpa‟‟ (Salla e Bashkisë) 13.00-14.00: Promovim i librit „‟Trupi im më përket mua‟‟ të autorit Kleo Lati (Salla e Bashkisë) 13.00-14.00: Promovim i librit “Mallkimi i priftëreshave të Ilirisë‟‟, Mira Meksi (Stenda SHB Toena). -

A1993literature.Pdf

ALBANIAN LITERATURE Robert Elsie (1993) 1. The historical background - II. Attributes of modern Albanian literature - III. Literature of the post-war period - IV. Literature of the sixties, seventies and eighties - V. Albanian literature in Kosovo - VI. Perspectives for the future - VII. Chronology of modern Albanian literature 1. The historical background Being at the crossroads between various spheres of culture has never been a gain to the Albanians as one might have expected. An Albanian national culture and literature1 was late to develop and had enormous difficulty asserting itself between the Catholic Latin civilization of the Adriatic coast, the venerable Orthodox traditions of the Greeks, Serbs and Bulgarians and the sophisticated Islamic culture of the Ottoman Empire. First non-literary traces of written Albanian are known from the 15th century, e. g. Bishop Paulus ’ baptismal formula of November 8, 1462. Beginning with the Missal (Meshari) of Gjon Buzuku2 in 1555, the early Albanian literature of the 16th and 17th century with its primarily religious focus might have provided a foundation for literary creativity in the age of the Counter- Reformation under the somewhat ambiguous patronage of the Catholic Church, had not the banners of Islam soon been unfurled on the eastern horizons. The Ottoman colonization of Albania, which had begun as early as 1385, was to split the Albanians definitively into three spheres of culture, all virtually independent of one another: 1) the cosmopolitan traditions of the Islamic Orient using initially -

DRITARJA NGA SHOHIM BOTËN LETËRSIA 6 Për Klasën E Gjashtë Të Shkollës Fillore LIBRI I MËSUESIT

Rrok Gjolaj ● Vjollca Osja DRITARJA NGA SHOHIM BOTËN LETËRSIA 6 Për klasën e gjashtë të shkollës fillore LIBRI I MËSUESIT Enti i Teksteve dhe i Mjeteve Mësimore PODGORICË, 2020 Rrok Gjolaj Vjollca Osja DRITARJA NGA SHOHIM BOTËN LETËRSIA 6 PËR KLASËN E GJASHTË TË SHKOLLËS FILLORE LIBRI I MËSUESIT PROZOR ZA GLEDANJE SVIJETA KNJIŽEVNOST 6 PRIRUČNIK ZA ŠESTI RAZRED OSNOVNE ŠKOLE Botuesi: Enti i Teksteve dhe i Mjeteve Mësimore; Podgoricë Për botuesin: Pavle Goranoviq Kryeredaktor: Radulle Novoviq Redaktor përgjegjës: Llazo Lekoviq Redaktor i librit: Dimitrov Popoviq Recensues: Dr. Marko Camaj Prof. dr. Alfred Çapaliku Aishe Resulbegoviq Prof. dr. Gëzim Dibra Prof.as.dr.Mithat Hoxha Dizajni dhe faqosja: studio ZUNS Korrektor: Dimitrov Popoviq Redaktore teknike: Dajana Vukçeviq CIP – Каталогизација у публикацији Национална библиотека Црне Горе, Цетиње ISBN 978-86-303-2382-9 COBISS.CG-ID 17037060 Këshilli Kombëtar i Arsimit, me vendimin nr. 10903-119/20-3335/14 të datës 24. 07. 2020 e miratoi këtë komplet të Тekstit mësimor për përdorim në shkollat fillore. Copyright © Enti i Teksteve dhe i Mjeteve Mësimore, Podgoricë, 2020 PËRMBAJTJA PARATHËNIE ............................................ 4 KAPITULLI I ............................................. 5 Gjergj Fishta: GJUHA SHQIPE. .........................................................6 Andon Z. Çajupit: FSHATI IM ..........................................................8 Lasgush Poradeci: KROI I FSHATIT TONË ...............................................10 Aleksa Shantiq: RRINI KËTU ...!” -

Download This PDF File

July 2020 e-ISSN: 1857-8187 p-ISSN: 1857-8179 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4149017 Case Study Linguistics ERROR ANALYSIS OF PASSIVE IN THE WRITINGS OF ALBANIAN Keywords: Be, modal, transitive, non-transitive, by, passive voice, contrastive analysis, error analysis, LEARNERS OF ENGLISH data analyzing. Përparim Skuka University of Tetova “Fadil Sulejmani”. North Macedonia. Abstract The aim of this thesis is the analysis of errors commonly madein the 9-th grade students in urban and rural Albanian schools in the academic year 2018-2019 in using the passive voice. A quantitative approach is applied in conducting the research. The samples of the research are24 students in both schools, 12 students in each school. The descriptive analysis method is going to beused in this research to find the errors of the students and to analyze the data. “The major focus of this study is the Contrastive Analysis between the English passive forms through their Albanian correspondents; contribute to the theoretical linguistics, to the general theory of contrastive linguistics, to the development of contrastive studies in Albanian, to the development of Albanian prescriptive grammars.”1 They are the theories of English grammar, Error analysis, and Language Teaching and Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis. Theory of English grammar was used to know and understand the structure of English passive voice.While, the theory of error analysis was used to analyze the student’ errors based on the Linguistic Category Taxonomy particularly for the English passive voice, and Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis was used to find out the similarity and the difference between English and Albanian passive voice. -

E 17 Exile and N 750'Den Bug Ostalgia in Güne Arnav Albanian L Vut Lirik

Mediterranean Journal of Humanities mjh.akdeniz.edu.tr I /1, 2011, 123-139 Exile and Nostalgia in Albanian LyL ric Poetryr since 1750 1750’den Bugüne Arnavut Lirik Şiirinde Sürgün ve Nosttalji Addam GOLDWYN* Abstrraact: Albanian literature in general – and poetry in particular – has received little scholarly attention outside the Balkans, and yet this literature haas much to offer reader and critic alike. Robert Elsie, one of the few Albanologists working in English, has brought attention to Albanian literaturre by way of several books of translation as well as critical works on politics, culture, history and individual authors. There is as yet no significant body of literary criticism which analyzes broad thematic trends and poetic memes in texts from a variety of periods and places. This essay seeks to serve as a foundatiion for this kind of synthetic scholarship. Through close readings of poems from the beginnings of Albanian literature to today on the inter-related themes of exile and nostalgia, this work emphasizes the evolution of Albanian attitudes about colonization and independence as they are viewed from at home and inn the diaspora. Keywoords: : Albania, exile, poetics, diaspora Özet: Genelde Arnavut edebiyatı ve özelde de Arnavut şiiri Balkan’ların dışına taşan bir akademik ilgiye sahip olmuştur; ancak halen okuyucu ve eleştirmenlere bu edebiyatın sunacakları çoktur. İngilizce yazan Arnavutbilimcilerden Robert Elsie yapmış olduğu çeviriler ve politik, kültürel, tarihseel ve bireysel yazan bir çok yazar hakkındaki eleştirileriyle Arnavvuut edebiyatını çalışan bir kaç kişiden birridir. Ancak, bir çok tarihsel dönem ve coğrafi bölgeden gelen edebi metinlerin konularını ve şiirsel özelliiklerini konu edinen çalışma halen çok azdır. -

Contrasting the Polysemy of Prepositions in English and Albanian

UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Contrasting the Polysemy of Prepositions in English and Albanian P.h. D. Dissertation presented by: Ardian Fera Supervised by: Professor Titular. Ignasi Navarro i Ferrando Castelló de la Plana, November, 2019 Doctoral Program in Applied Languages, Literature and Translation University Jaume I Doctoral School Contrasting the Polysemy of Prepositions in English and Albanian Report submitted by Ardian Fera in order to be eligible for a doctoral degree awarded by the Universitat Jaume I Doctoral Student Supervisor Ardian Fera Ignasi Navarro i Ferrando Castelló de la Plana, November, 2019 This is a Self-Funding Doctorate Thesis DEDICATION TO MY BELOVED PARENTS RESTING IN PEACE AND TO MY TWO LITTLE DAUGHTERS, ESTREA AND NEJMIA WHOM I LOVE SO MUCH This paper intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been possible without the prodigious, incomparable, heuristic and great help of my supervisor, Professor Titular. Ignasi Navarro i Ferrando, who stood close to me every step, whenever I needed, and provided everything necessary for the progress of my thesis. Many thanks go, too, to Renata Geld, Head of the English Department at the Faculty of Foreign Languages, Zagreb, Croatia, who, very conventionally conduced promising facilities during my Research Stay, there. Certainly, there’s also a place here to thank the head of the English Department and many of my colleagues at the Faculty of Foreign Languages, Tirana, Albania, who willingly shared with me very useful scientific knowledge throughout the days while at work. I would also like to thank the representatives of the University departments of Jaume I, who were always ready in fulfilling and replying many of my queries while working on my dissertation. -

4 Studime 21 Komplet

400 AShAK: Studime 21 - 2014 BIBLIOGRAFIA E BOTIMEVE TË PROFESOR SHABAN DEMIRAJT1 I. Vepra shkencore a) Pa ndonjë bashkëpunim 1. Çështje të sistemit emëror të gjuhës shqipe. Botim i Universitetit të Tiranës. Tiranë 1972, f. 296 (me një përmbledhje frëngjisht). 2. Sistemi i lakimit në gjuhën shqipe. Botim i Universitetit të Tiranës. Tiranë 1975, f 275 (me një përmbledhje frëngjisht). 3. Gramatikë historike e gjuhës shqipe. Botim i Universitetit të Tiranës. Shtëpia Botuese 8 Nëntori. Tiranë 1986, f. l167 (me një përmbledhje anglisht); Shtëpia Botuese Rilindja. Prishtinë 1988 2, f. 1047. 4. Gjuha shqipe dhe historia e saj. Botim i Universitetit të Tiranës. Tiranë 1988, f. 321 (me një përmbledhje anglisht); Rilindja. Prishtinë 19892, f. 290. 5. Eqrem Çabej – një jetë kushtuar shkencës. Shtëpia Botuese 8 Nëntori. Tiranë 1990, f. 272; Akademia e Shkencave të Shqipërisë. Tiranë 2008 2, f. 322. 6. Historische Grammatik der albanischen Sprache (kurze Fassung). Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften; Philosophisch – historische Klasse. Schriften der Balkan-Kommission. Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. Wien 1993, f. 366. 7. Gjuhësi ballkanike. Shtëpia Botuese Logos-A, në bashkëpunim me Katedrën e Gjuhës dhe të Letërsisë Shqiptare të Universitetit të Shkupit. Shkup 1994, f. 277 (me një përmbledhje anglisht). 8. Balkanska lingvistika = Gjuhësi ballkanike. Shtëpia botuese Logos A. Shkup 1994, f. 294 (me një përmbledhje anglisht). 9. Fonologjia historike e gjuhës shqipe. Botim i Akademisë së Shkencave të Shqipërisë. Shtëpia Botuese Toena. Tiranë 1996, f. 332 (me një permbledhje anglisht). 10. La lingua albanese – origine, storia, strutture. Centro Editoriale e Librario – Università degli Studi della Calabria. Rende – Italia 1997, f. -

Liber Leximi 7 FINAL Ver7:Layout 1.Qxd

FJALA Fjala t’urren – zhgënjen T’mallkon – qorton Ajo të shkel – përkëdhel Të zhduk – të shpik Fjala është ujë që freskon Zjarr që shkrumon O, ajo është kamxhik Që stuhitë i ndërsen i mund! Fjala është e thellë sa toka E lartë – sa qielli mbi koka E hidhët – sa mëkati Që në vete ndryn Fjala të zhvesh të ngjesh Të fryn e shfryn – E bukur është kur sjell lulzim në tokë. Abdylazis Islami Fjalë dhe shprehje zhgënjen – dëshpëron mëkat – gjynah, shkelje e rregullave fetare Bisedë rreth vjershës Ç’mendoni ju, për çfarë fjale mendon e flet poeti? Çfarë fuqie ka fjala? Me çka krahason poeti fuqinë e fjalës? Pse thotë poeti “fjala është ujë që freskon”? GJUHA SHQIPE DHE LEXIMI PËR KLASËN VII 7 Abdylazis Islami i lindur në f. Gajre të Tetovës, (1930 - 2005) është njëri prej shkrimtarëve më të njohur bashkëkohorë shqiptarë, i cili krijoi në gjuhën shqipe në R Maqedonisë. Me shkrime letrare filloi të merret herët (më 1954) dhe ka botuar më shumë përmbledhje me poezi dhe prozë. Shkroi për fëmijë dhe për të rritur. Për fëmijë ka botuar këto vepra: “Mëngjesi në fshat”, “Korrieri Artan Arta”, “Kujtime dhe ëndërrime” etj. Abdylazis Islami MËSUESI IM I PARË E kujtoj shumë herë mësuesin tim të parë. E kujtoj dhe mallëngjehem. Ne e donim dhe e respektonim shumë. Ai ishte një burrë me trup mesatar, i hequr në fytyrë. Nuk ish plak, po flokët i qenë zbardhur. Mbante një palë syze me xham të trashë. Ishte i ngadalshëm në të ecur dhe shumë i kujdesshëm në çdo punë. -

Historia E Letërsisë Shqipe

AKADEMIA E SHKENCAVE DHE E ARTEVE E KOSOVËS AKADEMIA E SHKENCAVE E SHQIPËRISË HISTORIA E LETËRSISË SHQIPE Materialet e Konferencës shkencore, 30-31 tetor 2009, në Prishtinë PRISHTINË 2010 KOSOVAACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF ALBANIA THE HISTORY OF ALBANIAN LITERATURE The Materials from the Scientific Conference, 30-31 October 2009, Prishtina Editorial board: Academician Ali Aliu, Academician Sabri Hamiti, Academician Mehmet Kraja Editor: Academician Mehmet Kraja, Secretary of the Section of Language and Literature PRISHTINË 2010 AKADEMIA E SHKENCAVE DHE E ARTEVE E KOSOVËS AKADEMIA E SHKENCAVE E SHQIPËRISË HISTORIA E LETËRSISË SHQIPE Materialet e Konferencës shkencore, 30-31 tetor 2009, në Prishtinë Këshilli redaktues: akademik Ali Aliu, akademik Sabri Hamiti, akademik Mehmet Kraja Redaktor: akademik Mehmet Kraja, sekretar i Seksionit të Gjuhësisë dhe të Letërsisë PRISHTINË 2010 Konferenca shkencore: Historia e Letërsisë Shqipe 5 PËRMBAJTJA PËRMBAJTJA ........................................................................................................... 5 Sabri HAMITI: HISTORI E LETËRSI (Referat hyrës) ............................................. 7 Ardian MARASHI: PSE, SI DHE KUSH DUHET TA RISHKRUAJË HISTORINË E LETËRSISË SHQIPE: TEZA PUNE ........................................ 23 Rusana HRISTOVA-BEJLERI: ASPEKTE TË SHKENCËS LETRARE KRAHASUESE NË STUDIMIN E HISTORISË SË LETËRSISË SHQIPE ..... 31 Sadri FETIU: VENDI I LETËRSISË POPULLORE NË HISTORINË E LETËRSISË SHQIPE ........................................................................................ -

The Education and Albanian Schools in Albania, During the Years 1905

8-10 September 2014- Istanbul, Turkey 971 Proceedings of SOCIOINT14- International Conference on Social Sciences and Humanities THE EDUCATION AND ALBANIAN SCHOOLS IN ALBANIA DURING THE YEARS 1905- 1908 Fatjon Kica1 1Phd student, third year, Tirana University, Albania, [email protected] Abstract The Cultural National Movement gave a great contribution for opening the Albanian schools and learning the Albanian Language during the years 1905-1908.This was a hard work due to the unfavorable conditions at this period. The members of the Cultural National Clubs were determined to reach their purposes. Clubs were broad democratic organizations which consisted on intellectuals, officers of the state apparatus teachers, representatives of civil bourgeoisie, the small producers and traders of the city and the village, the landowners, the officers and the people who were associated with the Ottoman rulers. Keywords: Cultural Club, Albanian Schools, the declaration of the constitution 1. INTRODUCTION The efforts of learning the Albanian Language with a single and common Albanian alphabet for all Albanians were not separated from the war for the rising of the Albanian people through the spread of knowledge in their native language, by opening of the Albanian schools. By opening and establishing of the Albanian schools, the spread of the national education, the rising of national Albanians and the country's progress that faced to many difficulties were impossible. By the time that was prevented the spread of learning the Albanian language, the government of the Sultan, allowed the opening of the foreign schools in Albania, especially Italian and Austrian Catholic schools. At the end of the XIX century and at the beginning of XX century, Austria-Hungary established schools in some cities of Albania such as in Tirana Shkoder, Durres, Milot, etc. -

3 Studime 21 Komplet

AShAK: Studime 21 - 2014 383 Shaban DEMIRAJ 1 DISA TË DHËNA NGA JETA IME Kam lindur në Vlorë, sipas dëshmisë së nënës sime, në mars të vitit 1921, por sipas regjistrimit zyrtar më 1 janar 1920, në Mëhallën e Re, (sot Lagjja Partizani). Babai im quhej Sulejman Demiraj, por në popull thirrej Mulla Sulo, sepse shërbente si imam në ish-xhaminë e Tabakëve, e cila u shkatërrua gjatë Luftës Antifashiste Nacionalçlirimtare. Familja jonë ka qenë e lidhur me atë luftë. Prandaj dy vëllezërit e mi të mëdhenj, Aliu dhe Shyqyriu u internuan dhe u vranë nga nazistët gjermanë. Pas Çlirimit ata janë shpallur dëshmorë. Babai më çoi në shkollën plotore të vetme të Vlorës pa mbushur gjashtë vjeç. Shkolla ndodhej në lagjen Muradije, afër sheshit të Flamurit, pra mjaft larg shtëpisë sonë në Lagjen e Re. Në shkollë shkoja bashkë me dy nipërit e mi, Mus- tafanë dhe Mynyrin, që ishin ndonjë vit më të mëdhenj se unë. Por më kujtohet se në shkollë veja me qejf, sepse babai më kishte abonuar te një furrxhi afër xhamisë së Tabakëve për të marrë një simite çerek-lekëshe, të cilën e haja thatë me dëshirë aq të madhe. Mësuesi i klasës së parë mbante llagapin Stringa dhe ka shumë të ngjarë që të ketë qenë nga fisi Stringa prej Elbasani. Në klasën e parë, në të dytën dhe në të tretën, me sa më kujtohet, nuk shkoja aq mirë me mësime, kurse në klasën e katërt nuk kalova dot, sepse vija edhe i imët me shëndet dhe bëja shumë mungesa dhe mësimet më dukeshin të vështira. -

Aspects of Narrative in the Prose of Writer Petro Marko

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF APPLIED LANGUAGE AND CULTURAL STUDIE (IJALSC) Vol. 2, No. 2, 2019. ASPECTS OF NARRATIVE IN THE PROSE OF WRITER PETRO MARKO Antela Voulis PhDc Center for Albanian Studies, Tirana E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Petro Marko is considered by critics as one of the founders of modern Albanian prose. Scientific assessments of Petro Markos’s creativity are mainly based on long and short prose, in the form of genuine critical studies, short predictions, comments and analyzes. There are papers of this nature written by scholars such as: Floresha Dado, Adriatik Kallulli, Bashkim Kuçuku, Ali Aliu, Robert Elsie and many others. The subject matter of these articles varies from simple information to moments of writer’s life, to genuine studies and analysis regarding interpretation and explanation of different elements of the structure of his literary works. In this case, we would like to highlight an article written by the author Bashkim Kuçuku, namely the novel “A name on four streets”. In this particular paper, Kucuku discusses the symbolism of the novel’s title, that even in its metaphorical form didn’t escape the punishment of dictatorship censure, closely connected with the tragic fate that followed Petro Marko. And by doing so the researcher gives us a detailed insight of the connection between his work and a broader background of Marco’s biography. In this context together with the detailed analysis of the novel’s title we will find the key point that paves the way for penetrating the original metaphor and symbolism of the story. According to Kuçuku, Petro Marko is a dignified, idealist, as well a stoic writer for justice and social equality.