Governance and Human Security in Anambra State, 1999-2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obumselu on African Literature

Obumselu on African Literature Obumselu on African Literature: The Intellectual Muse Edited by Isidore Diala Obumselu on African Literature: The Intellectual Muse Edited by Isidore Diala This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Ben Obumselu All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2305-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2305-0 For Professor Ben Obumselu: Master, mentor, model, and much more A solid academic, one of the pioneers of the distinctive University of Ibadan brand, and one whose personality helped to shape Nigeria’s collegial culture before its later debasement . This volume fills in a yawning gap in the compendium of African literary criticism, since Obumselu was such a reticent expositor of his own productivity. —Wole Soyinka Wherever Obumselu’s name was evoked, it was always with uncustomary reverence. The reverence was for his solid scholarship and perspicacious mind; his assured, limpid prose which lent to his pronouncements a kind of magisterial poise; his cool and classical power of exegesis. This compendium of Obumselu’s work is an invaluable contribution to the criticism of African literature. —Femi Osofisan This compendium is a welcome tribute to Ben Obumselu, one of the most widely read, liberally educated, and profoundly cerebral scholars Nigeria has ever produced. -

The Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics - An Open Access International Journal Vol.1 2013 The Literary Artist as a Mediator: the Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry Ade Adejumo (Ph.D) Department of General Studies, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology P.M.B. 4000, Ogbomoso,Oyo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper contends that there exists a paradoxical relationship between violence and conflictual situations on one hand, and the literary art on the other. While conflictual violence exerts tremendous strains on human relations, literary artists have often had their creative sensibilities fired by such conflicts. The above accounts for the emergence of the war-sired creative enterprise collectively referred to as war literature. These writers have used their art either as mere chronicles of the unfolding drama of blood and death or as interventionist art to preach peace and restoration of human values. Using the Nigerian experience, this paper does an examination of select corpus of poetry, which emanated from the Nigerian civil war experience. It isolates the messages of peace, which went a long way in not only pointing out the evils occasioned by war and conflict but also in suturing the broken ties of humanity while the war lasted. As our societies are becoming increasingly conflictual, our literary endeavours should also assume more social responsibilities in terms of conflict mitigation, prevention and promotion of global peace. This paper therefore envisions a new literary movement i.e. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

A GOLDEN JUBILEE PUBLICATION, EDITED by CHINUA ACHEBE Terri Ochiagha

Africa 85 (2) 2015: 191–220 doi:10.1017/S0001972014000990 THERE WAS A COLLEGE: INTRODUCING THE UMUAHIAN: A GOLDEN JUBILEE PUBLICATION, EDITED BY CHINUA ACHEBE Terri Ochiagha Because colonialism was essentially a denial of human worth and dignity, its education programme could not be a model of perfection. And yet the great thing about being human is our ability to face adversity down by refusing to be defined by it, refusing to be no more than its agent or victim. (Achebe 1993) Government College, Umuahia, one of Nigeria’s three leading colonial secondary schools, is known among literary critics around the world for being the alma mater of eight important Nigerian writers: Chinua Achebe, Chike Momah, Elechi Amadi, Chukwuemeka Ike, Christopher Okigbo, Gabriel Okara, Ken Saro- Wiwa and I. N. C. Aniebo. Many are the illustrious Nigerian scientists, intellec- tuals and public leaders who passed through the Umuahia Government College in its prime, and in Nigeria – and to a lesser extent in the former British Cameroons – the name of the school evokes an astounding range of success stories. But Umuahia’s legend as ‘the Eton of the East’ and the primus inter pares of Nigeria’s elite colonial institutions obscures its present reality: nothing remains of its magnificent past but its extensive grounds, landmark buildings, and the glittering roll call of Nigerian dignitaries who once studied within its walls. Upon a cursory search, the inquisitive web surfer is greeted by alarming synopses of the school’s current state and status: ‘Government College, Umuahia in tatters’, ‘Government College, Umuahia still crying for redemption’. -

TIE NIGERIAN LIIEFMY 8Fillsi W H.Ls. ~IEIY* by R.N

- 59 - TIE NIGERIAN LIIEFMY 8fillSI W H.lS. ~IEIY* by R.N. EGUOU In a very significant sense, there has always been an uneasy relationship (with varying degrees of seriousness in different places and at different times) between the artist and his society; and it seems to me that the current argument on the proper role of the African artist is part of an age-old tradltion in which the artist is continual ly being required, by society, to justify the social relevance of his art. One might note that as early as Plato, the artist was viewed suspiciously as a sort of moral hazard, a poor imitator who, because his medium is several removes from reality, can impair the reason and harm the good with his 'inferior degree of truth.' In Plato's opinion, the artist has no business in the well-ordered Republic un l ess he can show that there is "a use in poetry as well as a delight. "1 It was because the artist-dramatist was thought to be doing a moral disservice to his society that playhouses in England were closed down in 1642, and ordinances made in 1647 and 1648 "ordering players to be whipped and hearers to be fined."2 The zealous Puritans of the time saw the players and playhouses as disseminating disease and ungodliness, and as dwelling •amid incest. horrors. and perversities." 3 By the Victorian era, the doctrine of 'moral aesthetic' had become the principal yardstick for assessing all literary works. To the traditional Victorians, art lies between religion and hygiene, and hygiene meant the health of the body politic. -

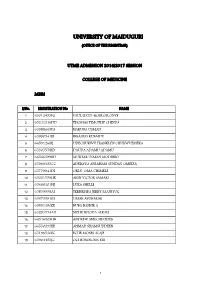

Unimaid Utme 2016 2017 First Batch

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION 2016/2017 SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICINE MBBS S/No. REGISTRATION No. NAME 1 65012453FG PAUL LIZZY-ROSE OILONYE 2 65241316DD THOMAS TIMOTHY CHINDA 3 65988663FA HARUNA USMAN 4 65880541EI IBRAHIM KUBAIDU 5 66531268IJ UDECHUKWU FRANKLYN CHUKWUEMEKA 6 65305578ID DAUDA ADAMU ADAMU 7 66546199BD MUKTAR USMAN MODIBBO 8 65989125CC ADEBAYO ABRAHAM SUNDAY OMEIZA 9 65759941DI ORLU-OMA CHIMELE 10 65021759HE AKIN VICTOR SAMARI 11 65488101HJ LUKA SHELLE 12 65859958AI TERHEMBA JERRY SAANIYOL 13 65875581IH UMAR ABUBAKAR 14 65891180EE BUBA BASHIR A 15 65295774AH NUHU RHODA ALKALI 16 66546503HB ANDREW MELCHIZEDEK 17 66550295EE AHMAD SHAMSUDDEEN 18 65198536EC ECHE MOSES ALAJE 19 65904453JC OCHE PRINCESS EHI 1 20 65299718AJ ABDULMUMIN ABUBAKAR 21 65459752FH OBI SOMTO 22 65780434FH JATTO ISA ENERO 23 66200732GG MICHAEL BLESSING 24 66299464BB MICHAEL KISLON SHITNAN 25 65903857DH USMAN ADAMA 26 66215998FC GWASKI ISAAC DIKA 27 66496897JB MOHAMMED ADAMU DUMBULWA 28 65243376GB TAHIR MUHAMMAD ARABO 29 66048182HA JERRY LEAH 30 65885079BE AHMED ABBA 31 65858960JC GAMBO LAWI 32 66246168ED SAMAILA BITRUS VISION 33 65919477CI OBI PETER CHIGOZIE 34 65548790IB GADZAMA JANADA YOHANNA 35 66193123AB MOSES MATTHEW TAIYE 36 65780170HD AERNAN SEDOO 37 65786350GA ZAKARIYYA ABDULMUMIN SANI 38 66324429JH OJIMADU CHIDINDU GODSWILL 39 65527190IF MBAYA ENOCH SAMUEL 40 65199053ED GAGA TERNGUNAN ERIC 41 65534793HB ROBERT RAKEAL 42 65305105EH YAK'OR TONGRIYANG DAWEET 43 65299765GC GONI AISHA UMAR 44 65136595BD AFOLABI ABDULWAHAB -

THE ROLE of JUDGES in the ELECTION PROCESS Abstract

MUNFOLLJ (3) 2021 THE ROLE OF JUDGES IN THE ELECTION PROCESS Abstract Election has been universally acclaimed as a process of choosing representatives by popular vote by the people in a democratic society. It is one of the attributes of democracy. Election in Nigeria is conducted by an independent Electoral body, Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) which is expected to carry out its statutory duties in compliance with the constitution and other enactments and, at the end of the Election process declare a winner in the Election. All contestants in the Election have the constitutional right to ventilate their grievance against the conduct of the Election in the Court or Election Tribunal and the judgment of the Court or Tribunal is binding on all the parties, including INEC. This Paper examines on the Role of Judges in the Election process and the numerous factors which obstruct the Judges in the discharge of their roles in Election matters. It is the findings that the Judges are not adequately discharging their roles in Election matters hence there is no justice and fairness with the resultant lack of confidence by the citizenry on the Courts / Election Tribunals handling Election matters. In conclusion the work recommends that Keywords: Democracy, Election Petition, INEC, Judge 1.0. INTRODUCTION Democracy which has been affirmed as the best form of government in the world, no doubt is a government made up of the generality or representatives of the people. It allows the people to participate in the government by choosing their leaders. Such leaders are chosen in regular and periodic Elections which is one of its attributes. -

File Download

Fashioning the Modern African Poet Nathan Suhr-Sytsma, Emory University Book Title: Poetry, Print, and the Making of Postcolonial Literature Publisher: Cambridge University Press Publication Place: New York, NY Publication Date: 2017-07-31 Type of Work: Chapter | Final Publisher PDF Permanent URL: https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/s9wnq Final published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/9781316711422 Copyright information: This material has been published in Poetry, Print, and the Making of Postcolonial Literature by Nathan Suhr-Sytsma. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. © Nathan Suhr-Sytsma 2017. Accessed September 25, 2021 6:50 PM EDT chapter 3 Fashioning the Modern African Poet DEAD: Christopher Okigbo, circa 37, member of Mbari and Black Orpheus Committees, publisher, poet ; killed in battle at Akwebe in September 1967 on the Nsukka sector of the war in Nigeria fighting on the secessionist side ...1 So began the first issue of Black Orpheus to appear after the departure of its founding editor, Ulli Beier, from Nigeria. Half a year had passed since the start of the civil war between Biafran and federal Nigerian forces, and this brief notice bears signs of the time’s polarized politics. The editors, J. P. Clark and Abiola Irele, proceed to announce “the poem opening on the opposite page”–more accurately, the sequence of poems, Path of Thunder – as “the ‘last testament’ known of this truly Nigerian character,” reclaiming Christopher Okigbo from Biafra for Nigeria at the same time as they honor his writing. -

Living the Myth: Revisiting Okigbo's Art and Commitment

Dan Izevbaye Living the myth: Revisiting Okigbo’s Dan Izevbaye is Dean of the Faculty of art and commitment Social and Management Sciences, Bowen University, Iwo, Nigeria; he was previously Professor of English at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. E-mail: [email protected] Living the myth: Revisiting Okigbo’s art and commitment This is a study of the nature and sources of the persona’s quest in Christopher Okigbo’s poetry. The protagonist in Okigbo’s writing explores the fluid borders between aesthetic and spiritual states, with language and social action as instruments of the self’s aspiration towards spiritual and aesthetic fulfillment. Although Okigbo’s narration is presented in the form of dramatic ritual, the distance or severance of the material from the poet’s own spiritual history is not total, for the historical content eventually intrudes into the writing and reestablishes the authentic autobiography of the poetic self. The historical context, the 1960s, is an age of transition. Okigbo’s characterisation of his persona as an actor in a state of personal transition reflects the poet’s sensitive immersion in the spirit of his times and establishes Okigbo the poet as perhaps its ideal representative. One of the issues raised in this study is that in spite of the protagonist’s recurrent return to the point of passage, there is a relentless drive towards death seen ambiguously as the ultimate goal and state of perfection as well as the perfect form of transition. The central question explored in this study is the roles of poetic diction, the tense politics of the 1960s and the poet’s own intense temperament in determining his peculiar choice of resolution to the dilemma at the centre of his poetry. -

The Center for Research Libraries Scans to Provide Digital Delivery of Its Holdings

The Center for Research Libraries scans to provide digital delivery of its holdings. In some cases problems with the quality of the original document or microfilm reproduction may result in a lower quality scan, but it will be legible. In some cases pages may be damaged or missing. Files include OCR (machine searchable text) when the quality of the scan and the language or format of the text allows. If preferred, you may request a loan by contacting Center for Research Libraries through your Interlibrary Loan Office. Rights and usage Materials digitized by the Center for Research Libraries are intended for the personal educational and research use of students, scholars, and other researchers of the CRL member community. Copyrighted images and texts may not to be reproduced, displayed, distributed, broadcast, or downloaded for other purposes without the expressed, written permission of the copyright owner. Center for Research Libraries Identifier: f-n-000001 Downloaded on: Jun 15, 2017 5:03:23 PM r:; • lifgSit ■ » Federal RepubUc of Nigeria Official Gazette No. 36 Lagos - 12th July, 1973 Vol. 60 CONTENTS Page Page Movements • e . 1018-26 Establishment of Denton StreetPostal Agency, Ebute Metta ■ 4 • • » ■ e 1029 Yaba College of Tec^ology—Appointment (States Representatives of Coun^) Notice 1072 «« «« «a •• a, aa lyin Postal Agency—^Introduction of Savings 1026 Bank Fadlities 1030 Yaba College of Technology—Appointment Loss of Local Purchase Orders .. 1030 (States Representatives of Coun^) Notice 1973 .. .. 1626 Loss of local Purchase Order Booklet .. 1030 Applications under Trade Unions Act Cap. Loss of Payable Orders .. 1030 200 Laws of the Federation of Nigeria and Federal Government Bursary Scheme for the Lagos 1958 • • . -

Sovereign-Trust-Insurance-2011-Annual-Report.Pdf

1 A N N U A L R E P O R T & A C C O U N T S 2 0 1 1 V I S I O N To be a leading brand providing insurance and financial services of global standards. M I S S I O N To enhance the every day life of our customers t h ro u g h i n n o v a t i v e insurance and financial services while creating exceptional value for our shareholders. CORE VALUES Superior Customer Service Innovation Professionalism Integrity Empathy Team Spirit. A N N U A L R E A C C O P O R T U N T S & 2 2 0 1 1 Notice of AGM 03 Corporate Information 05 Management Team 07 Financial Highlights 08 Chairman’s Statement 09 Board of Directors 14 Management Team 18 Directors’ Report 24 Statement of Directors' Responsibilities 31 Independent Auditor’s Report 32 C O N T E N T S Report of the Audit Committee 33 Statement of Significant Accounting Policies 34 Balance Sheet 40 Profit and Loss Account 41 Revenue Account 42 Statement of Cash Flow 43 Notes to the Financial Statements 45 Statement of Value Added 63 Five-Year Financial Summary 64 Share Capital History 65 Mandate Form 66 Proxy Form 67 Admission Form 68 Unclaimed Dividend Warrant List 69 3 A N N U A L R E P O R T & A C C O U N T S 2 0 1 1 1 7 T H A G M N O T I C E 4 A N N U A L R E P O R T & A C C O U N T S 2 0 1 1 N O T I C E O F T H E 1 7 T H A N N U A L G E N E R A L M E E T I N G TO ALL THE SHAREHOLDERS NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL NOTES CLOSURE OF REGISTER MEETING PROXIES The Register of members and Only a member of the Company Transfer Books of the Company shall NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN to you entitled to attend and vote at the be closed from 24th day of May that the 17th Annual General General Meeting is entitled to 2012 to 31st day of May 2012 (both Meeting of Sovereign Trust appoint a proxy in his/her stead. -

Governance and Insecurity in South East Nigeria.Pmd

GOVERNANCE AND INSECURITYYY IN SOUTH EAST NIGERIA Edited by: Ukoha Ukiwo and Innocent Chukwuma CLEEN Foundation First published in 2012 by: CLEEN Foundation Lagos Office: 21, Akinsanya Street Taiwo Bus-Stop Ojodu Ikeja, 100281 Ikeja, Lagos, Nigeria Tel: 234-1-7612479, 7395498 Abuja Office: 26, Bamenda Street, off Abidjan Street Wuse Zone 3, Abuja, Nigeria Tel: 234-9-7817025, 8708379 Owerri Office: Plot 10, Area M Road 3 World Bank Housing Estate Owerri, Imo State Tel: 083-823104, 08128002962, 08130278469 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.cleen.org ISBN: 978-978-51062-2-0 © Whole or part of this publication may be republished, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted through electronic, photocopying, mechanical, recording or otheriwe, with proper acknowledgement of the publishers. Typesetting: Blessing Aniche-Nwokolo Cover concept: Gabriel Akinremi The mission of CLEEN Foundation is to promote public safety, security and accessible justice through empirical research, legislative advocacy, demonstration programmes and publications, in partnership with government and civil society. Table of Content List of tables v Acknowledgement vi Preface viii Chapters: 1. Framework for Improving Security and Governance in the Southeast by Ukoha Ukiwo 1 2. Governance and Security in Abia State by Ukoha Ukiwo and Magdalene O Emole 24 3. Governance and Security in Anambra State by Chijoke K. Iwuamadi 58 4. Governance and Security in Ebonyi State by Smart E. Otu 83 5. Governance and Security in Enugu State by Nkwachukwu Orji 114 6. Governance and Security