The Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747 University Of Namibia NEPAL 001252 Tribhuvan University NETHERLANDS 004215 A T College 002311 Acad Voor Gezondheidszorg 004215 Atc 004510 Baarns Lyceum 000109 Catholic University Tilburg 000107 Catholic University, Nijmegan 000101 Delft University Of Technology 002272 Dordrecht Polytech 004266 Eindhoven Sec Schl 000102 Eindhoven Univ Technology 002452 Enschede College 000108 Erasmus Univ Rotterdam 000100 Free Univ Amsterdam 002984 Haarlem Business School 000112 Institute Of Social Studies 000113 Int Inst Aero Survey& Space Sc 004751 Katholieke Scholengemeenschap 002461 Netherlands School Of Business 000114 Philips Int Inst Tech Studies 046294 Rijksuniversiteit Leiden 000115 Royal Tropical Institute 004152 Schola Europaea Bergensis 000104 State Univ Groningen 000105 State Univ Leiden 000106 State Univ Limburg 000110 State Univ Utrecht 002430 State University Of Utrecht 004276 Stedelijk Gymnasium 002543 Technische Hogeschool Rijswijk 003615 The British Sch /netherlands 002452 Twentse Academie Voor Fysiothe 000099 Univ Amsterdam 000103 University Of Twente 002430 University Of Utrecht 000111 Wageningen Agricultural Univ 002242 Wageningen Agricultural Univ NETHERLANDS ANTILLES 002476 Univ Netherlands Antilles NEW ZEALAND 000758 Lincoln Col Canterbury 000759 Massey Univ Palmerston 000756 The University Of Auckland 000757 Univ Canterbury 000760 Univ Otago 000762 Univ Waikato International Schools 000761 Victoria Univ Wellington NICARAGUA 000210 Univ Centroamericana 000209 Univ Na Auto Nicaragua -

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: a Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: A Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi by Akinyemi Yetunde Blessing [email protected] Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria Abstract In this paper an attempt is made to examine the mythic narratives and ritual performances in olojo festival and to discuss the traditional involvement of the Ooni of Ife during the festivals, making reference to the late Ọợni Adesoji Adėrėmí. This paper also investigates the implication of local, national and international politics on the traditional festival in Ile-Ife. The importance of the study arrives as a result of the significance of the Ile-Ife amidst the Yoruba towns. More so, festivals have cultural significance that makes some unique turning point in the history of most Yoruba society. Ǫlợjợ festival serves as the worship of deities and a bridge between the society and the spiritual world. It is also a day to celebrate the re-enactment of time. Ǫlợjợ festival demands the full participation of the reigning Ọợni of Ife. The result of the field investigation revealed that the myth of Ǫlợjợ festival remains, but several changes have crept into the ritual process and performances during the reign of the late Adesoji Adėrėmí. The changes vary from the ritual time, space, actions and amidst the ritual specialists. It is found out that some factors which influence these changes include religious contestation, ritual modernization, economics and political change not at the neglect of the king’s involvement in the local, national and international politics which has given space for questioning the Yoruba kingship institution. -

When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire Under Historial Review

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo1 1) Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission, Nigeria Date of publication: November 30th, 2014 Edition period: November 2014 – March 2015 To cite this article: Ojo, M.O.D. (2014). When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 248-267. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 No.3 November 2014 pp. 248-267 When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historical Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission Abstract Using historical events research approach and qualitative key informant interview, this study examined how religion failed to stop political crisis that happened in the old Western region of Nigeria. Ikire, in the present Osun State of Nigeria was used as a case study. The study investigated the incidences of killing, arson and exile that characterized the crisis in the town which served as the case study. It argued that the two prominent political figures which started the crisis failed to apply the religious doctrines of love, peace and brotherhood which would have solved the crisis before it spread to all parts of the Old Western Region of Nigeria and the entire nation. -

Obumselu on African Literature

Obumselu on African Literature Obumselu on African Literature: The Intellectual Muse Edited by Isidore Diala Obumselu on African Literature: The Intellectual Muse Edited by Isidore Diala This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Ben Obumselu All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-2305-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-2305-0 For Professor Ben Obumselu: Master, mentor, model, and much more A solid academic, one of the pioneers of the distinctive University of Ibadan brand, and one whose personality helped to shape Nigeria’s collegial culture before its later debasement . This volume fills in a yawning gap in the compendium of African literary criticism, since Obumselu was such a reticent expositor of his own productivity. —Wole Soyinka Wherever Obumselu’s name was evoked, it was always with uncustomary reverence. The reverence was for his solid scholarship and perspicacious mind; his assured, limpid prose which lent to his pronouncements a kind of magisterial poise; his cool and classical power of exegesis. This compendium of Obumselu’s work is an invaluable contribution to the criticism of African literature. —Femi Osofisan This compendium is a welcome tribute to Ben Obumselu, one of the most widely read, liberally educated, and profoundly cerebral scholars Nigeria has ever produced. -

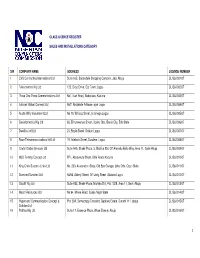

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics

NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS VOLUME 4 NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY, 2014 CONTENTS PAGE Onu, J.O., J.N. Nmadu and L. Tanko: Determinants of Awareness of Credit Procurement Procedures and Farmers Income In Minna Metropolis, Nigeria 1-11 Adeolu B. Ayanwale and Christianah A. Amusan: Gender Analysis of Rice Production Efficiency in Osun State: Implication for the Transformation Agenda 12-24 Obayelu A. E. and Obayelu, O. A.: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis of the Nigeria Agricultural Transformation Agenda 25-43 Kareem, R.O, Ayinde, I.A, Bakare H.A, and Bashir, N.O: Determinants of Aggregate Agricultural Supply Response in Nigeria (1960-2010) 44-57 Obayelu, A.E., Arowolo, A.O., Ibrahim S.B. and Croffie A.Q: Economics of Fresh Tomato Marketing in Kosofe Local Government Area Of Lagos State, Nigeria 58-67 Ayinde, O. E, Adewumi, M.O., Nmadu, J. N., Olatunji, G. B and Egbugo K.: Review of Marketing Board Policy: Comparative Analysis Cocoa of Pricing Eras In Nigeria 68-79 Ayinde, I. A., Kareem, R. O. and Lasisi, K.: Economic Assessment of the Effect of the Nigerian Technology Incubation Programme on Agro-Allied Small and Medium Scale Enterprises 80-92 Authors Guide: Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics 93-94 Published by the Nigerian Association of Agricultural Economists Editorial Board Editorial Policy Editor-in-Chief Prof. Foluso Okunmadewa, The Journal serves mainly as a medium for Sector Leader, Human Development the publication of scientific research outputs World Bank Africa Region in all fields of Agricultural Economics and Country Office, Abuja, Nigeria allied disciplines. It also publishes review articles and theoretical papers (research Assistant Editors-in-Chief papers, review articles) concerned with Prof Ben Hammed, agricultural development in the tropical Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria world and Nigeria in particular. -

A GOLDEN JUBILEE PUBLICATION, EDITED by CHINUA ACHEBE Terri Ochiagha

Africa 85 (2) 2015: 191–220 doi:10.1017/S0001972014000990 THERE WAS A COLLEGE: INTRODUCING THE UMUAHIAN: A GOLDEN JUBILEE PUBLICATION, EDITED BY CHINUA ACHEBE Terri Ochiagha Because colonialism was essentially a denial of human worth and dignity, its education programme could not be a model of perfection. And yet the great thing about being human is our ability to face adversity down by refusing to be defined by it, refusing to be no more than its agent or victim. (Achebe 1993) Government College, Umuahia, one of Nigeria’s three leading colonial secondary schools, is known among literary critics around the world for being the alma mater of eight important Nigerian writers: Chinua Achebe, Chike Momah, Elechi Amadi, Chukwuemeka Ike, Christopher Okigbo, Gabriel Okara, Ken Saro- Wiwa and I. N. C. Aniebo. Many are the illustrious Nigerian scientists, intellec- tuals and public leaders who passed through the Umuahia Government College in its prime, and in Nigeria – and to a lesser extent in the former British Cameroons – the name of the school evokes an astounding range of success stories. But Umuahia’s legend as ‘the Eton of the East’ and the primus inter pares of Nigeria’s elite colonial institutions obscures its present reality: nothing remains of its magnificent past but its extensive grounds, landmark buildings, and the glittering roll call of Nigerian dignitaries who once studied within its walls. Upon a cursory search, the inquisitive web surfer is greeted by alarming synopses of the school’s current state and status: ‘Government College, Umuahia in tatters’, ‘Government College, Umuahia still crying for redemption’. -

TIE NIGERIAN LIIEFMY 8Fillsi W H.Ls. ~IEIY* by R.N

- 59 - TIE NIGERIAN LIIEFMY 8fillSI W H.lS. ~IEIY* by R.N. EGUOU In a very significant sense, there has always been an uneasy relationship (with varying degrees of seriousness in different places and at different times) between the artist and his society; and it seems to me that the current argument on the proper role of the African artist is part of an age-old tradltion in which the artist is continual ly being required, by society, to justify the social relevance of his art. One might note that as early as Plato, the artist was viewed suspiciously as a sort of moral hazard, a poor imitator who, because his medium is several removes from reality, can impair the reason and harm the good with his 'inferior degree of truth.' In Plato's opinion, the artist has no business in the well-ordered Republic un l ess he can show that there is "a use in poetry as well as a delight. "1 It was because the artist-dramatist was thought to be doing a moral disservice to his society that playhouses in England were closed down in 1642, and ordinances made in 1647 and 1648 "ordering players to be whipped and hearers to be fined."2 The zealous Puritans of the time saw the players and playhouses as disseminating disease and ungodliness, and as dwelling •amid incest. horrors. and perversities." 3 By the Victorian era, the doctrine of 'moral aesthetic' had become the principal yardstick for assessing all literary works. To the traditional Victorians, art lies between religion and hygiene, and hygiene meant the health of the body politic. -

Introduction and General Framework Aims and Methodology One of The

1 Introduction and General Framework Aims and Methodology One of the aims of this academic work is to discuss the Niger Delta conflict, by analyzing the behavior of the actors and players involved in the conflict. The discussions in this paper, looks critically at the activities of the major actors in the conflict: The behavior of the Nigerian government, the unprecedented actions of the different militia groups in the region and the activities of the multi-national oil companies operating in the region. The thesis started by analyzing the history of the region and the process of human right activism, from its non-violent struggle, up to the stages of arm confrontation and the subsequence outbreak of full scale arm race. In particular, the study focuses on the Nigerian government and the militia groups in the region. Less emphasis are made on the activities of the Multi-national oil companies because the paper looks at the activities of oil companies as a complementary behavior with the Nigerian government hence the reciprocal actions of the militia groups are seen as counter behavioral attitude against, both the oil companies and the government. Second aim for this research thesis is aimed at identifying the existing problems regarding the Niger Delta conflict and to develop solution based arguments. Thirdly, this research thesis is aimed at internationalizing the Niger Delta conflict through broader based discussions, and if possibly third party involvement, such as the United Nations, the European Union, and the United States, in finding a comprehensive and lasting solutions to the over six decades long crisis. -

The First Republic and the Interface of Ethnicity and Resource Allocation in Nigeria’S First Republic

Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences Volume 2, No. 2.2 Quarter II 2011 ISSN 2229 – 5313 THE FIRST REPUBLIC AND THE INTERFACE OF ETHNICITY AND RESOURCE ALLOCATION IN NIGERIA’S FIRST REPUBLIC Ekanade Olumide, Department of History and International Relations, Redeemer’s University, Nigeria Tinuola Ekanade, Doctoral Student, Department of Geography, University of Ibadan, Nigeria . ABSTRACT In 1960, Britain bequeathed to Nigeria an imperfect Federation, consisting of three uneven regions. This lopsided arrangement, paved the way for the domination of the federation by the biggest region- (Northern region) This paper adopts the instrumentalist view of federalism. It interrogates the impact of ethnicity on allocation of federal finance in Nigeria between 1960 and 1966. The paper explores the constitutional basis for revenue distribution and the process of subversion by the ruling party. It examines the various mechanisms employed by the North to appropriate federal patronage for its region at the expense of other regions in the period. The paper contends that the unequal access to and competition for scarce resources at the Centre made politics become a dangerous enterprise. The ruling elite (Northerners) seized this opportunity to institutionalize iniquitous fiscal policies which snowballed into political tribulations in the first republic. Till date the ethnic factor continues to play a pivotal role in the political economy of resource sharing in Nigeria. The paper concludes that Nigeria has not been able to manage the challenge of revenue allocation well because the ruling class has been sectional and corrupt. .Much more importantly the ability of the North through the instrumentality of the Central government to dominate its competitors engendered serious crisis in the Nigerian federation which eventually led to the political instability that engulfed the first republic and led to its demise in 1966. -

Evaluation of Automated Cataloguing System in Academic Libraries in Oyo State Nigeria Oluwole A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln January 2019 Evaluation of Automated Cataloguing System in Academic Libraries in Oyo State Nigeria Oluwole A. Odunola Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, [email protected] A Tella University of Ilorin, Ilorin Nigeria, [email protected] O O. Oyewumi Ladoke Akintola University of Technology,Ogbomoso. Oyo State,Nigeria, [email protected] T A. Ogunmodede Ladoke Akintola University of Technology,Ogbomoso. Oyo State,Nigeria, [email protected] S O. Oyetola Ladoke Akintola University of Technology,Ogbomoso. Oyo State,Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Odunola, Oluwole A.; Tella, A; Oyewumi, O O.; Ogunmodede, T A.; and Oyetola, S O., "Evaluation of Automated Cataloguing System in Academic Libraries in Oyo State Nigeria" (2019). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 2152. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2152 EVALUATION OF AUTOMATED CATALOGUING SYSTEM IN ACADEMIC LIBRARIES IN OYO STATE NIGERIA Odunola, O. A. [email protected] Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Oyewumi, O. O. [email protected] Deputy Librarian Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Ogunmodede, T. A. [email protected] Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Oyetola, S. O. [email protected] Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Daniel, O. University of Ibadan, Ibadan Nigeria. Abstract This study investigated automated cataloguing system in academic libraries in selected higher institutions in Oyo State Nigeria. -

Local Institutions, Fetish Oaths and Blind Loyalties to Political Godfathers in South-Western Nigeria

Local Institutions, Fetish Oaths and Blind Loyalties to Political Godfathers in South-Western Nigeria Olusegun Afuape, Lagos State Polytechnic, Lagos, Nigeria The IAFOR North American Conference on the Social Sciences Official Conference Proceedings 2014 Abstract This paper examines the involvement of traditional rulers and other institutions such as Community Development Association (CDA) and Community Development Council (CDC) in the mobilization for both local and General Elections in south- western Nigeria. It argues that the upgrading of some village heads to the position of kings, together with the creation of the position where it was hitherto non-existent, as well as secret but fetish oaths of loyalty sworn to by political sons/daughters to guarantee their loyalty, is deliberately done with a view to using them as a veritable tool to mobilize for grassroots support during General Elections. Using interview and observation, the conceptual framework for this study is David Easton's system analysis and this is augmented with the theory of violence as espoused by Hannah Arendt and Jenny Pearce. The problems created by the politicization of these institutions are blind loyalty of traditional leaders, politicians and members of community associations to the political Godfathers, deification of these Godfathers, imposition of unpopular and incompetent candidates in political offices, misappropriation of public funds and all manner of corruption, among others. Hence, the required remedies to these factors are proffered after which this paper concludes that for violence to disappear, there is the need for political gladiators and electorate to desist and resist the politicization of local institutions and the installation of literate and non-violent candidates as either a village head or a king.