Introduction and General Framework Aims and Methodology One of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. the Secession of Biafra, 1967–1970

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2020-06 Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa Thomas, Charles G.; Falola, Toyin University of Calgary Press Thomas, C. G., & Falola, T. (2020). Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/112216 book https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca SECESSION AND SEPARATIST CONFLICTS IN POSTCOLONIAL AFRICA By Charles G. Thomas and Toyin Falola ISBN 978-1-77385-127-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission. -

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747 University Of Namibia NEPAL 001252 Tribhuvan University NETHERLANDS 004215 A T College 002311 Acad Voor Gezondheidszorg 004215 Atc 004510 Baarns Lyceum 000109 Catholic University Tilburg 000107 Catholic University, Nijmegan 000101 Delft University Of Technology 002272 Dordrecht Polytech 004266 Eindhoven Sec Schl 000102 Eindhoven Univ Technology 002452 Enschede College 000108 Erasmus Univ Rotterdam 000100 Free Univ Amsterdam 002984 Haarlem Business School 000112 Institute Of Social Studies 000113 Int Inst Aero Survey& Space Sc 004751 Katholieke Scholengemeenschap 002461 Netherlands School Of Business 000114 Philips Int Inst Tech Studies 046294 Rijksuniversiteit Leiden 000115 Royal Tropical Institute 004152 Schola Europaea Bergensis 000104 State Univ Groningen 000105 State Univ Leiden 000106 State Univ Limburg 000110 State Univ Utrecht 002430 State University Of Utrecht 004276 Stedelijk Gymnasium 002543 Technische Hogeschool Rijswijk 003615 The British Sch /netherlands 002452 Twentse Academie Voor Fysiothe 000099 Univ Amsterdam 000103 University Of Twente 002430 University Of Utrecht 000111 Wageningen Agricultural Univ 002242 Wageningen Agricultural Univ NETHERLANDS ANTILLES 002476 Univ Netherlands Antilles NEW ZEALAND 000758 Lincoln Col Canterbury 000759 Massey Univ Palmerston 000756 The University Of Auckland 000757 Univ Canterbury 000760 Univ Otago 000762 Univ Waikato International Schools 000761 Victoria Univ Wellington NICARAGUA 000210 Univ Centroamericana 000209 Univ Na Auto Nicaragua -

Federalism and Political Problems in Nigeria Thes Is

/V4/0 FEDERALISM AND POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN NIGERIA THES IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Olayiwola Abegunrin, B. S, Denton, Texas August, 1975 Abegunrin, Olayiwola, Federalism and PoliticalProblems in Nigeria. Master of Arts (Political Science), August, 1975, 147 pp., 4 tables, 5 figures, bibliography, 75 titles. The purpose of this thesis is to examine and re-evaluate the questions involved in federalism and political problems in Nigeria. The strategy adopted in this study is historical, The study examines past, recent, and current literature on federalism and political problems in Nigeria. Basically, the first two chapters outline the historical background and basis of Nigerian federalism and political problems. Chapters three and four consider the evolution of federal- ism, political problems, prospects of federalism, self-govern- ment, and attainment of complete independence on October 1, 1960. Chapters five and six deal with the activities of many groups, crises, military coups, and civil war. The conclusions and recommendations candidly argue that a decentralized federal system remains the safest way for keeping Nigeria together stably. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES0.0.0........................iv LIST OF FIGURES . ..... 8.............v Chapter I. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .1....... Geography History The People Background to Modern Government II. THE BASIS OF NIGERIAN POLITICS......32 The Nature of Politics Cultural Factors The Emergence of Political Parties Organization of Political Parties III. THE RISE OF FEDERALISM AND POLITICAL PROBLEMS IN NIGERIA. ....... 50 Towards a Federation Constitutional Developments The North Against the South IV. -

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: a Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: A Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi by Akinyemi Yetunde Blessing [email protected] Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria Abstract In this paper an attempt is made to examine the mythic narratives and ritual performances in olojo festival and to discuss the traditional involvement of the Ooni of Ife during the festivals, making reference to the late Ọợni Adesoji Adėrėmí. This paper also investigates the implication of local, national and international politics on the traditional festival in Ile-Ife. The importance of the study arrives as a result of the significance of the Ile-Ife amidst the Yoruba towns. More so, festivals have cultural significance that makes some unique turning point in the history of most Yoruba society. Ǫlợjợ festival serves as the worship of deities and a bridge between the society and the spiritual world. It is also a day to celebrate the re-enactment of time. Ǫlợjợ festival demands the full participation of the reigning Ọợni of Ife. The result of the field investigation revealed that the myth of Ǫlợjợ festival remains, but several changes have crept into the ritual process and performances during the reign of the late Adesoji Adėrėmí. The changes vary from the ritual time, space, actions and amidst the ritual specialists. It is found out that some factors which influence these changes include religious contestation, ritual modernization, economics and political change not at the neglect of the king’s involvement in the local, national and international politics which has given space for questioning the Yoruba kingship institution. -

When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire Under Historial Review

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo1 1) Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission, Nigeria Date of publication: November 30th, 2014 Edition period: November 2014 – March 2015 To cite this article: Ojo, M.O.D. (2014). When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 248-267. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 No.3 November 2014 pp. 248-267 When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historical Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission Abstract Using historical events research approach and qualitative key informant interview, this study examined how religion failed to stop political crisis that happened in the old Western region of Nigeria. Ikire, in the present Osun State of Nigeria was used as a case study. The study investigated the incidences of killing, arson and exile that characterized the crisis in the town which served as the case study. It argued that the two prominent political figures which started the crisis failed to apply the religious doctrines of love, peace and brotherhood which would have solved the crisis before it spread to all parts of the Old Western Region of Nigeria and the entire nation. -

South – East Zone

South – East Zone Abia State Contact Number/Enquires ‐08036725051 S/N City / Town Street Address 1 Aba Abia State Polytechnic, Aba 2 Aba Aba Main Park (Asa Road) 3 Aba Ogbor Hill (Opobo Junction) 4 Aba Iheoji Market (Ohanku, Aba) 5 Aba Osisioma By Express 6 Aba Eziama Aba North (Pz) 7 Aba 222 Clifford Road (Agm Church) 8 Aba Aba Town Hall, L.G Hqr, Aba South 9 Aba A.G.C. 39 Osusu Rd, Aba North 10 Aba A.G.C. 22 Ikonne Street, Aba North 11 Aba A.G.C. 252 Faulks Road, Aba North 12 Aba A.G.C. 84 Ohanku Road, Aba South 13 Aba A.G.C. Ukaegbu Ogbor Hill, Aba North 14 Aba A.G.C. Ozuitem, Aba South 15 Aba A.G.C. 55 Ogbonna Rd, Aba North 16 Aba Sda, 1 School Rd, Aba South 17 Aba Our Lady Of Rose Cath. Ngwa Rd, Aba South 18 Aba Abia State University Teaching Hospital – Hospital Road, Aba 19 Aba Ama Ogbonna/Osusu, Aba 20 Aba Ahia Ohuru, Aba 21 Aba Abayi Ariaria, Aba 22 Aba Seven ‐ Up Ogbor Hill, Aba 23 Aba Asa Nnetu – Spair Parts Market, Aba 24 Aba Zonal Board/Afor Une, Aba 25 Aba Obohia ‐ Our Lady Of Fatima, Aba 26 Aba Mr Bigs – Factory Road, Aba 27 Aba Ph Rd ‐ Udenwanyi, Aba 28 Aba Tony‐ Mas Becoz Fast Food‐ Umuode By Express, Aba 29 Aba Okpu Umuobo – By Aba Owerri Road, Aba 30 Aba Obikabia Junction – Ogbor Hill, Aba 31 Aba Ihemelandu – Evina, Aba 32 Aba East Street By Azikiwe – New Era Hospital, Aba 33 Aba Owerri – Aba Primary School, Aba 34 Aba Nigeria Breweries – Industrial Road, Aba 35 Aba Orie Ohabiam Market, Aba 36 Aba Jubilee By Asa Road, Aba 37 Aba St. -

The Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics - An Open Access International Journal Vol.1 2013 The Literary Artist as a Mediator: the Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry Ade Adejumo (Ph.D) Department of General Studies, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology P.M.B. 4000, Ogbomoso,Oyo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper contends that there exists a paradoxical relationship between violence and conflictual situations on one hand, and the literary art on the other. While conflictual violence exerts tremendous strains on human relations, literary artists have often had their creative sensibilities fired by such conflicts. The above accounts for the emergence of the war-sired creative enterprise collectively referred to as war literature. These writers have used their art either as mere chronicles of the unfolding drama of blood and death or as interventionist art to preach peace and restoration of human values. Using the Nigerian experience, this paper does an examination of select corpus of poetry, which emanated from the Nigerian civil war experience. It isolates the messages of peace, which went a long way in not only pointing out the evils occasioned by war and conflict but also in suturing the broken ties of humanity while the war lasted. As our societies are becoming increasingly conflictual, our literary endeavours should also assume more social responsibilities in terms of conflict mitigation, prevention and promotion of global peace. This paper therefore envisions a new literary movement i.e. -

Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board

JOINT ADMISSIONS AND MATRICULATION BOARD APPLICATION STATISTICS BY INTITUTION AND GENDER (AGE LESS THAN 16) S/NO INSTITUTION F M TOTAL 1 ABUBAKAR TAFAWA BALEWA UNIVERSITY, BAUCHI, BAUCHI STATE 78 89 167 2 ACHIEVERS UNIVERSITY, OWO, ONDO STATE 3 0 3 3 ADAMAWA STATE UNIVERSITY, MUBI, ADAMAWA STATE 8 5 13 4 ADEKUNLE AJASIN UNIVERSITY, AKUNGBA-AKOKO, ONDO STATE 169 68 237 5 ADELEKE UNIVERSITY, EDE, OSUN STATE 6 4 10 6 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO STATE. (AFFL TO OAU, ILE-IFE) 8 4 12 7 ADEYEMI COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, ONDO, ONDO STATE 1 0 1 8 AFE BABALOLA UNIVERSITY, ADO-EKITI, EKITI STATE 92 71 163 9 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY TEACHING HOSPITAL, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 2 0 2 10 AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA, KADUNA STATE 826 483 1309 11 AIR FORCE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, KADUNA, KADUNA STATE 2 1 3 12 AJAYI CROWTHER UNIVERSITY, OYO, OYO STATE 6 1 7 13 AKANU IBIAM FEDERAL POLYTECHNIC, UNWANA, AFIKPO, EBONYI STATE 5 3 8 14 AKWA IBOM STATE UNIVERSITY, IKOT-AKPADEN, AKWA IBOM STATE 39 28 67 15 AKWA-IBOM STATE POLYTECHNIC, IKOT-OSURUA, AKWA IBOM STATE 7 3 10 16 ALEX EKWUEME FEDERAL UNIVERSITY, NDUFU-ALIKE, EBONYI STATE 55 33 88 17 AL-HIKMAH UNIVERSITY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE 3 1 4 18 AL-QALAM UNIVERSITY, KATSINA, KATSINA STATE 6 1 7 19 ALVAN IKOKU COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, IMO STATE, (AFFL TO UNIV OF NIGERA, NSUKKA) 3 1 4 20 AMBROSE ALLI UNIVERSITY, EKPOMA, EDO STATE 208 117 325 21 AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, YOLA, ADAMAWA STATE 4 8 12 22 AMINU DABO COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KANO, KANO STATE 1 0 1 23 ANCHOR UNIVERSITY, AYOBO, LAGOS STATE -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT FEBRUARY 13, 2019 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Nkwor Market Square, Adazi- Enu, Anaocha Local Govt, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 16 Adazi-Nnukwu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Near Eke Market, Adazi Nnukwu, Adazi, Anambra State ANAMBRA 17 Addosser Microfinance Bank Limited State 32, Lewis Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State LAGOS 18 Adeyemi College Staff Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Adeyemi College of Education Staff Ni 1, CMS Ltd Secretariat, Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo ONDO 19 Afekhafe Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit No. -

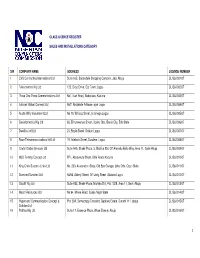

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics

NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS VOLUME 4 NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY, 2014 CONTENTS PAGE Onu, J.O., J.N. Nmadu and L. Tanko: Determinants of Awareness of Credit Procurement Procedures and Farmers Income In Minna Metropolis, Nigeria 1-11 Adeolu B. Ayanwale and Christianah A. Amusan: Gender Analysis of Rice Production Efficiency in Osun State: Implication for the Transformation Agenda 12-24 Obayelu A. E. and Obayelu, O. A.: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis of the Nigeria Agricultural Transformation Agenda 25-43 Kareem, R.O, Ayinde, I.A, Bakare H.A, and Bashir, N.O: Determinants of Aggregate Agricultural Supply Response in Nigeria (1960-2010) 44-57 Obayelu, A.E., Arowolo, A.O., Ibrahim S.B. and Croffie A.Q: Economics of Fresh Tomato Marketing in Kosofe Local Government Area Of Lagos State, Nigeria 58-67 Ayinde, O. E, Adewumi, M.O., Nmadu, J. N., Olatunji, G. B and Egbugo K.: Review of Marketing Board Policy: Comparative Analysis Cocoa of Pricing Eras In Nigeria 68-79 Ayinde, I. A., Kareem, R. O. and Lasisi, K.: Economic Assessment of the Effect of the Nigerian Technology Incubation Programme on Agro-Allied Small and Medium Scale Enterprises 80-92 Authors Guide: Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics 93-94 Published by the Nigerian Association of Agricultural Economists Editorial Board Editorial Policy Editor-in-Chief Prof. Foluso Okunmadewa, The Journal serves mainly as a medium for Sector Leader, Human Development the publication of scientific research outputs World Bank Africa Region in all fields of Agricultural Economics and Country Office, Abuja, Nigeria allied disciplines. It also publishes review articles and theoretical papers (research Assistant Editors-in-Chief papers, review articles) concerned with Prof Ben Hammed, agricultural development in the tropical Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria world and Nigeria in particular. -

The First Republic and the Interface of Ethnicity and Resource Allocation in Nigeria’S First Republic

Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences Volume 2, No. 2.2 Quarter II 2011 ISSN 2229 – 5313 THE FIRST REPUBLIC AND THE INTERFACE OF ETHNICITY AND RESOURCE ALLOCATION IN NIGERIA’S FIRST REPUBLIC Ekanade Olumide, Department of History and International Relations, Redeemer’s University, Nigeria Tinuola Ekanade, Doctoral Student, Department of Geography, University of Ibadan, Nigeria . ABSTRACT In 1960, Britain bequeathed to Nigeria an imperfect Federation, consisting of three uneven regions. This lopsided arrangement, paved the way for the domination of the federation by the biggest region- (Northern region) This paper adopts the instrumentalist view of federalism. It interrogates the impact of ethnicity on allocation of federal finance in Nigeria between 1960 and 1966. The paper explores the constitutional basis for revenue distribution and the process of subversion by the ruling party. It examines the various mechanisms employed by the North to appropriate federal patronage for its region at the expense of other regions in the period. The paper contends that the unequal access to and competition for scarce resources at the Centre made politics become a dangerous enterprise. The ruling elite (Northerners) seized this opportunity to institutionalize iniquitous fiscal policies which snowballed into political tribulations in the first republic. Till date the ethnic factor continues to play a pivotal role in the political economy of resource sharing in Nigeria. The paper concludes that Nigeria has not been able to manage the challenge of revenue allocation well because the ruling class has been sectional and corrupt. .Much more importantly the ability of the North through the instrumentality of the Central government to dominate its competitors engendered serious crisis in the Nigerian federation which eventually led to the political instability that engulfed the first republic and led to its demise in 1966.