The First Republic and the Interface of Ethnicity and Resource Allocation in Nigeria’S First Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747

SUBSTR DESCR International Schools NAMIBIA 002747 University Of Namibia NEPAL 001252 Tribhuvan University NETHERLANDS 004215 A T College 002311 Acad Voor Gezondheidszorg 004215 Atc 004510 Baarns Lyceum 000109 Catholic University Tilburg 000107 Catholic University, Nijmegan 000101 Delft University Of Technology 002272 Dordrecht Polytech 004266 Eindhoven Sec Schl 000102 Eindhoven Univ Technology 002452 Enschede College 000108 Erasmus Univ Rotterdam 000100 Free Univ Amsterdam 002984 Haarlem Business School 000112 Institute Of Social Studies 000113 Int Inst Aero Survey& Space Sc 004751 Katholieke Scholengemeenschap 002461 Netherlands School Of Business 000114 Philips Int Inst Tech Studies 046294 Rijksuniversiteit Leiden 000115 Royal Tropical Institute 004152 Schola Europaea Bergensis 000104 State Univ Groningen 000105 State Univ Leiden 000106 State Univ Limburg 000110 State Univ Utrecht 002430 State University Of Utrecht 004276 Stedelijk Gymnasium 002543 Technische Hogeschool Rijswijk 003615 The British Sch /netherlands 002452 Twentse Academie Voor Fysiothe 000099 Univ Amsterdam 000103 University Of Twente 002430 University Of Utrecht 000111 Wageningen Agricultural Univ 002242 Wageningen Agricultural Univ NETHERLANDS ANTILLES 002476 Univ Netherlands Antilles NEW ZEALAND 000758 Lincoln Col Canterbury 000759 Massey Univ Palmerston 000756 The University Of Auckland 000757 Univ Canterbury 000760 Univ Otago 000762 Univ Waikato International Schools 000761 Victoria Univ Wellington NICARAGUA 000210 Univ Centroamericana 000209 Univ Na Auto Nicaragua -

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: a Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi

The Influence of the Kingship Institution on Olojo Festival in Ile-Ife: A Case Study of the Late Ooni Adesoji Aderemi by Akinyemi Yetunde Blessing [email protected] Institute of African Studies, University of Ibadan, Oyo state, Nigeria Abstract In this paper an attempt is made to examine the mythic narratives and ritual performances in olojo festival and to discuss the traditional involvement of the Ooni of Ife during the festivals, making reference to the late Ọợni Adesoji Adėrėmí. This paper also investigates the implication of local, national and international politics on the traditional festival in Ile-Ife. The importance of the study arrives as a result of the significance of the Ile-Ife amidst the Yoruba towns. More so, festivals have cultural significance that makes some unique turning point in the history of most Yoruba society. Ǫlợjợ festival serves as the worship of deities and a bridge between the society and the spiritual world. It is also a day to celebrate the re-enactment of time. Ǫlợjợ festival demands the full participation of the reigning Ọợni of Ife. The result of the field investigation revealed that the myth of Ǫlợjợ festival remains, but several changes have crept into the ritual process and performances during the reign of the late Adesoji Adėrėmí. The changes vary from the ritual time, space, actions and amidst the ritual specialists. It is found out that some factors which influence these changes include religious contestation, ritual modernization, economics and political change not at the neglect of the king’s involvement in the local, national and international politics which has given space for questioning the Yoruba kingship institution. -

When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire Under Historial Review

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://rimcis.hipatiapress.com When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo1 1) Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission, Nigeria Date of publication: November 30th, 2014 Edition period: November 2014 – March 2015 To cite this article: Ojo, M.O.D. (2014). When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historial Review. International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences, 3(3), 248-267. doi: 10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/rimcis.2014.39 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). RIMCIS – International and Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Sciences Vol. 3 No.3 November 2014 pp. 248-267 When Religion Cannot Stop Political Crisis in the Old Western Region of Nigeria: Ikire under Historical Review Matthias Olufemi Dada Ojo Crawford University of the Apostolic Faith Mission Abstract Using historical events research approach and qualitative key informant interview, this study examined how religion failed to stop political crisis that happened in the old Western region of Nigeria. Ikire, in the present Osun State of Nigeria was used as a case study. The study investigated the incidences of killing, arson and exile that characterized the crisis in the town which served as the case study. It argued that the two prominent political figures which started the crisis failed to apply the religious doctrines of love, peace and brotherhood which would have solved the crisis before it spread to all parts of the Old Western Region of Nigeria and the entire nation. -

The Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Literature, Languages and Linguistics - An Open Access International Journal Vol.1 2013 The Literary Artist as a Mediator: the Case of Nigerian Civil War Poetry Ade Adejumo (Ph.D) Department of General Studies, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology P.M.B. 4000, Ogbomoso,Oyo State, Nigeria. e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper contends that there exists a paradoxical relationship between violence and conflictual situations on one hand, and the literary art on the other. While conflictual violence exerts tremendous strains on human relations, literary artists have often had their creative sensibilities fired by such conflicts. The above accounts for the emergence of the war-sired creative enterprise collectively referred to as war literature. These writers have used their art either as mere chronicles of the unfolding drama of blood and death or as interventionist art to preach peace and restoration of human values. Using the Nigerian experience, this paper does an examination of select corpus of poetry, which emanated from the Nigerian civil war experience. It isolates the messages of peace, which went a long way in not only pointing out the evils occasioned by war and conflict but also in suturing the broken ties of humanity while the war lasted. As our societies are becoming increasingly conflictual, our literary endeavours should also assume more social responsibilities in terms of conflict mitigation, prevention and promotion of global peace. This paper therefore envisions a new literary movement i.e. -

Hospital Cash Approved Providers List

HOSPITAL CASH APPROVED PROVIDERS LIST S/N PROVIDER NAME ADDRESS REGION STATE 1 Life care clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street Aba, Aba Abia 2 New Era Hospital 213/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba Aba Abia 3 J-Medicare Hospital 73, Bonny Street, Umuahia By Enugu Road Umuahia Abia 4 New Era Hospital 90B Orji River Road, Umuahia Umuahia Abia 10,Mobolaji Johnson street,Apo Quarters,Zone Abuja Abuja 5 Rouz Hospital & Maternity D,2nd Gate,Gudu District 6 Sisters of Nativity Hospital Phase 1, Jikwoyi, abuja municipal Area Council Abuja Abuja 7 Royal Lords Hospital, Clinics & Maternity Ltd Plot 107, Zone 4, Dutse Alhaji, Abuja Dutse Alhaji Abuja 8 Adonai Hospital 3, Adonai Close, Mararaba, Garki Garki Abuja Plot 202, Bacita Close, Off Plateau Street, Area 2 , Garki Abuja 9 Dara Clinics Garki FHA Lugbe FHA Estate, Lugbe, Abuja Lugbe Abuja 10 PAAFAG Hospital & Medical Diagnosis Centre 11 Central Hospital, Masaka Masaka Masaka Abuja 12 Pan Raf Hospital Limited Nyanya Phase 4 Nyanya Abuja Ahoada Close, By Nta Headquarters, Besides Uba, Abuja Abuja 13 Kinetic Hospital Area 11 14 Lona City Care Hospital 48, Transport Abuja Abuja Plot 145, Kutunku, Near Radio House, Gwagwalada Abuja 15 Jerab Hospital Gwagwalada 16 Paakag Hospital & Medical Diagnosis Centre Fha Lugbe, Fha Estate, Lugbe, Abuja Lugbe Abuja 17 May Day Hospital 1, Mayday Hospital Street, Mararaba, Abuja Mararaba Abuja 18 Suzan Memorial Hospital Uphill Suleja, Near Suleja Club, Gra, Suleja Suleja Abuja 64, Moses Majekodunmi Crescent,Utako, Abuja Utako Abuja 19 Life Point Medical Centre 7, Sirasso Close, Off Sirasso Crescent, Zone 7, Wuse Abuja 20 Health Gate Hospital Wuse. -

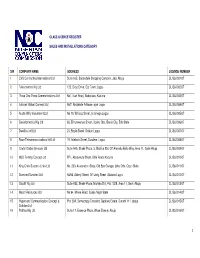

S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER SALES AND INSTALLATIONS CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/S&I/001/07 2 Telesciences Nig Ltd 123, Olojo Drive, Ojo Town, Lagos CL/S&I/002/07 3 Three One Three Communications Ltd No1, Isah Road, Badarawa, Kaduna CL/S&I/003/07 4 Latshak Global Concept Ltd No7, Abolakale Arikawe, ajah Lagos CL/S&I/004/07 5 Austin Willy Investment Ltd No 10, Willisco Street, Iju Ishaga Lagos CL/S&I/005/07 6 Geoinformatics Nig Ltd 65, Erhumwunse Street, Uzebu Qtrs, Benin City, Edo State CL/S&I/006/07 7 Dwellins Intl Ltd 21, Boyle Street, Onikan Lagos CL/S&I/007/07 8 Race Telecommunications Intl Ltd 19, Adebola Street, Surulere, Lagos CL/S&I/008/07 9 Clarfel Global Services Ltd Suite A45, Shakir Plaza, 3, Michika Strt, Off Ahmadu Bello Way, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/009/07 10 MLD Temmy Concept Ltd FF1, Abeoukuta Street, Bida Road, Kaduna CL/S&I/010/07 11 King Chris Success Links Ltd No, 230, Association Shop, Old Epe Garage, Ijebu Ode, Ogun State CL/S&I/011/07 12 Diamond Sundries Ltd 54/56, Adeniji Street, Off Unity Street, Alakuko Lagos CL/S&I/012/07 13 Olucliff Nig Ltd Suite A33, Shakir Plaza, Michika Strt, Plot 1029, Area 11, Garki Abuja CL/S&I/013/07 14 Mecof Resources Ltd No 94, Minna Road, Suleja Niger State CL/S&I/014/07 15 Hypersand Communication Concept & Plot 29A, Democracy Crescent, Gaduwa Estate, Durumi 111, abuja CL/S&I/015/07 Solution Ltd 16 Patittas Nig Ltd Suite 17, Essence Plaza, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja CL/S&I/016/07 1 17 T.J. -

Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics

NIGERIAN JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL ECONOMICS VOLUME 4 NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY, 2014 CONTENTS PAGE Onu, J.O., J.N. Nmadu and L. Tanko: Determinants of Awareness of Credit Procurement Procedures and Farmers Income In Minna Metropolis, Nigeria 1-11 Adeolu B. Ayanwale and Christianah A. Amusan: Gender Analysis of Rice Production Efficiency in Osun State: Implication for the Transformation Agenda 12-24 Obayelu A. E. and Obayelu, O. A.: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats (SWOT) Analysis of the Nigeria Agricultural Transformation Agenda 25-43 Kareem, R.O, Ayinde, I.A, Bakare H.A, and Bashir, N.O: Determinants of Aggregate Agricultural Supply Response in Nigeria (1960-2010) 44-57 Obayelu, A.E., Arowolo, A.O., Ibrahim S.B. and Croffie A.Q: Economics of Fresh Tomato Marketing in Kosofe Local Government Area Of Lagos State, Nigeria 58-67 Ayinde, O. E, Adewumi, M.O., Nmadu, J. N., Olatunji, G. B and Egbugo K.: Review of Marketing Board Policy: Comparative Analysis Cocoa of Pricing Eras In Nigeria 68-79 Ayinde, I. A., Kareem, R. O. and Lasisi, K.: Economic Assessment of the Effect of the Nigerian Technology Incubation Programme on Agro-Allied Small and Medium Scale Enterprises 80-92 Authors Guide: Nigerian Journal of Agricultural Economics 93-94 Published by the Nigerian Association of Agricultural Economists Editorial Board Editorial Policy Editor-in-Chief Prof. Foluso Okunmadewa, The Journal serves mainly as a medium for Sector Leader, Human Development the publication of scientific research outputs World Bank Africa Region in all fields of Agricultural Economics and Country Office, Abuja, Nigeria allied disciplines. It also publishes review articles and theoretical papers (research Assistant Editors-in-Chief papers, review articles) concerned with Prof Ben Hammed, agricultural development in the tropical Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria world and Nigeria in particular. -

4.11 Nigeria Additional Services Contact List

4.11 Nigeria Additional Services Contact List Type of Company Loca Street / Physical Address Name Title Email Phone Number (office) Website Description of Service tion Services (s) Provided Telecomm Airtel Natio Plot L2 Banana Island, https://www.airtel. +234 802 150 0111, +234 http://www. mobile network unications Nigeria nal Foreshore Estate, Ikoyi, Lagos com.ng/contact_us 802 150 0121 africa.airtel. facilities, internet- provider State, com/wps network provider airtelpremier@ng. /wcm/connect and airtel.com /africarevamp telecommunicatio /Nigeria/ n services. Telecomm 9Mobile Natio Ropp House [email protected]. 08090000200 https://9mobil mobile network unications (previously nal Plot 1774 Adetokunbo ng e.com.ng facilities, internet- provider Estilat) Ademola Crescent Wuse 2, /home/ network provider Abuja and , FCT, telecommunicatio n services. Telecomm MTN Natio Churchgate towers, 5th Floor, https://mtnonline.com +234 80310180, +234 http://www. mobile network unications Nigeria nal Plot 30, Afribank street, /about-mtn/contact- 80310188 mtnonline. facilities, internet- provider Victoria Island, Lagos Stat us com network provider 80310180 and telecommunicatio n services Banking United Natio UBA House 57 Marina. P O www.ubagroup.com +234 7002255822 cfc@ubagrou Currency and Bank for nal Box 2406 Lagos, Nigeria p.com exchange,wire Financial Africa transfers, loans services and all other banking services Banking Zenith Natio Plot 84, Ajose Adeogun Street, https://www. zenithdirect@z Currency and Bank nal Victoria Island, Lagos. Nigeria zenithbank.com/ enithbank.com exchange, wire Financial + 234-1-2787000 transfers, loans services and all other banking services Banking First Bank Natio Samual Asabia House, 35 https://www. +234 1 4485500 firstcontact@fir Currency and of Nigeria nal Marina Lagos, Nigeria firstbanknigeria. -

Introduction and General Framework Aims and Methodology One of The

1 Introduction and General Framework Aims and Methodology One of the aims of this academic work is to discuss the Niger Delta conflict, by analyzing the behavior of the actors and players involved in the conflict. The discussions in this paper, looks critically at the activities of the major actors in the conflict: The behavior of the Nigerian government, the unprecedented actions of the different militia groups in the region and the activities of the multi-national oil companies operating in the region. The thesis started by analyzing the history of the region and the process of human right activism, from its non-violent struggle, up to the stages of arm confrontation and the subsequence outbreak of full scale arm race. In particular, the study focuses on the Nigerian government and the militia groups in the region. Less emphasis are made on the activities of the Multi-national oil companies because the paper looks at the activities of oil companies as a complementary behavior with the Nigerian government hence the reciprocal actions of the militia groups are seen as counter behavioral attitude against, both the oil companies and the government. Second aim for this research thesis is aimed at identifying the existing problems regarding the Niger Delta conflict and to develop solution based arguments. Thirdly, this research thesis is aimed at internationalizing the Niger Delta conflict through broader based discussions, and if possibly third party involvement, such as the United Nations, the European Union, and the United States, in finding a comprehensive and lasting solutions to the over six decades long crisis. -

Evaluation of Automated Cataloguing System in Academic Libraries in Oyo State Nigeria Oluwole A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln January 2019 Evaluation of Automated Cataloguing System in Academic Libraries in Oyo State Nigeria Oluwole A. Odunola Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, [email protected] A Tella University of Ilorin, Ilorin Nigeria, [email protected] O O. Oyewumi Ladoke Akintola University of Technology,Ogbomoso. Oyo State,Nigeria, [email protected] T A. Ogunmodede Ladoke Akintola University of Technology,Ogbomoso. Oyo State,Nigeria, [email protected] S O. Oyetola Ladoke Akintola University of Technology,Ogbomoso. Oyo State,Nigeria, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Odunola, Oluwole A.; Tella, A; Oyewumi, O O.; Ogunmodede, T A.; and Oyetola, S O., "Evaluation of Automated Cataloguing System in Academic Libraries in Oyo State Nigeria" (2019). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 2152. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/2152 EVALUATION OF AUTOMATED CATALOGUING SYSTEM IN ACADEMIC LIBRARIES IN OYO STATE NIGERIA Odunola, O. A. [email protected] Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Oyewumi, O. O. [email protected] Deputy Librarian Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Ogunmodede, T. A. [email protected] Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Oyetola, S. O. [email protected] Olusegun Oke Library, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Ogbomoso, Nigeria Daniel, O. University of Ibadan, Ibadan Nigeria. Abstract This study investigated automated cataloguing system in academic libraries in selected higher institutions in Oyo State Nigeria. -

Local Institutions, Fetish Oaths and Blind Loyalties to Political Godfathers in South-Western Nigeria

Local Institutions, Fetish Oaths and Blind Loyalties to Political Godfathers in South-Western Nigeria Olusegun Afuape, Lagos State Polytechnic, Lagos, Nigeria The IAFOR North American Conference on the Social Sciences Official Conference Proceedings 2014 Abstract This paper examines the involvement of traditional rulers and other institutions such as Community Development Association (CDA) and Community Development Council (CDC) in the mobilization for both local and General Elections in south- western Nigeria. It argues that the upgrading of some village heads to the position of kings, together with the creation of the position where it was hitherto non-existent, as well as secret but fetish oaths of loyalty sworn to by political sons/daughters to guarantee their loyalty, is deliberately done with a view to using them as a veritable tool to mobilize for grassroots support during General Elections. Using interview and observation, the conceptual framework for this study is David Easton's system analysis and this is augmented with the theory of violence as espoused by Hannah Arendt and Jenny Pearce. The problems created by the politicization of these institutions are blind loyalty of traditional leaders, politicians and members of community associations to the political Godfathers, deification of these Godfathers, imposition of unpopular and incompetent candidates in political offices, misappropriation of public funds and all manner of corruption, among others. Hence, the required remedies to these factors are proffered after which this paper concludes that for violence to disappear, there is the need for political gladiators and electorate to desist and resist the politicization of local institutions and the installation of literate and non-violent candidates as either a village head or a king. -

About LAUTECH

About LAUTECH OVERVIEW OF LAUTECH Ladoke Akintola University of Technology is an autonomous public institution with the general function of providing liberal higher education and encouragement to the rapid advancement of learning throughoutNigeria. The legal basis of the University is the Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Act which transferred to the University, the property to the former Ogbomoso Girls High School, Ogbomoso, under the Act; - The University consists of Chancellor, pro-chancellor, Vice-Chancellor, Council Senate, Congregation, all Graduates and Undergraduates of the University in accordance with the provisions of the Ladoke Akintola University of Technology Edict No The university runs three academic programmes: pre-degree science programme, undergraduate programmes and post-graduate programmes. The university is jointly owned by two states in Nigeria:Oyo and Osun states. The entire student body population is presently about 20,000. For two consequtive seasons, 2003 and 2004, the university has been adjudged by the Nigerian Universities Commission (NUC) as the best state university in Nigeria. The university has two campuses: ogbomoso and osogbo campuses and is currently made up of six faculties and a college. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The conception of the University began in 1987 when Governor Adetunji Olurin, the then Military Governor of Oyo State, responding to a letter from the Governing Council of the Polytechnic Ibadan set up a seven member interministerial committee under the chairperson of Mrs. Oyinkan Ayoola. The Committee submitted its report in 1988 and recommended the establishment of a State University. In response to their submission, a 15-member committee of distinguished academicians under the chairmanship of Professor J.