Ritual Movement in the City of Lalitpur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Body As Theatre in Bode Jatra

Body as Theatre in Bode Jatra A Dissertation Presented to the Central Department of English, Tribhuvan University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy By Hukum Thapa Central Department of English Tribhuvan University January, 2010 DISSERTATION APPROVAL We hereby recommend that the dissertation entitled “ Body as Theatre in Bode Jatra ” by Hukum Thapa be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the Master of Philosophy in English degree. ---------------------------------------------------- Supervisor ---------------------------------------------------- External Examiner Date: ---------------------------- Table of Contents Pages Dissertation Approval Acknowledgements Abstracts Chapter 1. Body and Ritual 1 2. Locating body in Newari Cultural Performance 24 3. Body as Theatre in Bode Jatra 38 4. Conclusion 62 5. Works Cited 6. Appendix I: Questionnaires Acknowledgements This dissertation owes much to the encouragement and shared knowledge offered by my advisor Prof.Dr.Abhi Subedi and my colleague cum teacher Dr.Shiv Rijal.Their brainwaves inspired me to delve into the performance study and to engross in the research of pioneering field of relation between body –theatre and theatre-ritual. Their association with the theatre for a long time whipped up support to lay bare snooping in the theatricality. I am grateful to Sajib Shrestha, Juju Bhai Bas Shrestha and Dil Krishna Prajapati of Bode for communicating copious facets of Bode Jatra , whose descriptions on Bode Jatra lent me a hand to bring it in such a silhouette. I would also like to thank the locals of Bode for their hold up to amass the information and cross the threshold of their cultural heritage that grew to be a foundation to put the last touches on my mission. -

The Journey of Nepal Bhasa from Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018

Center for Sami Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization — Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies May 2018 The Journey of Nepal Bhasa From Decline to Revitalization A thesis submitted by Resha Maharjan Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies The Centre of Sami Studies (SESAM) Faculty of Humanities, Social Science and Education UIT The Arctic University of Norway May 2018 Dedicated to My grandma, Nani Maya Dangol & My children, Prathamesh and Pranavi मा車भाय् झीगु म्हसिका ख: (Ma Bhay Jhigu Mhasika Kha) ‘MOTHER TONGUE IS OUR IDENTITY’ Cover Photo: A boy trying to spin the prayer wheels behind the Harati temple, Swoyambhu. The mantra Om Mane Padme Hum in these prayer wheels are written in Ranjana lipi. The boy in the photo is wearing the traditional Newari dress. Model: Master Prathamesh Prakash Shrestha Photo courtesy: Er. Rashil Maharjan I ABSTRACT Nepal Bhasa is a rich and highly developed language with a vast literature in both ancient and modern times. It is the language of Newar, mostly local inhabitant of Kathmandu. The once administrative language, Nepal Bhasa has been replaced by Nepali (Khas) language and has a limited area where it can be used. The language has faced almost 100 years of suppression and now is listed in the definitely endangered language list of UNESCO. Various revitalization programs have been brought up, but with limited success. This main goal of this thesis on Nepal Bhasa is to find the actual reason behind the fall of this language and hesitation of the people who know Nepal Bhasa to use it. -

E-Magazine 209-20

केन्द्रीय वि饍यालय भारतीय राजदतू ािास काठमा赍डू KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU Vidyalaya Patrika 2019-20 Kendriya Vidyalaya EOI Kathmandu, Nepal VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 1 ) KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU PATRON H.E. Manjeev Singh Puri, Ambassador, Embassy of India CHAIRMAN, VMC Dr. Ajay Kumar, DCM EOI NOMINEE CHAIRMAN, VMC Sh. Abhishek Dubey, First Secretary (PIC), EOI Editorial Board Mr. R.K.G Pandey PGT Hindi Mr. Pinaki Bandyopadhyaya PGT English Mrs. D. Lakshmi Rao TGT English Mr. Sadagopan TGT Sanskrit Mr. Kamal Jit, PRT Mr. A Venkata Ramana, SSA Students Member BHUWAN RATHI XII-A PRASHASTI ARYAL XII-B ADITYA KUSHWAHA XI-A ANSHITA NAHATA XI-B VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 2 ) KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 3 ) KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 4 ) KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 5 ) KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 6 ) KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 7 ) KENDRIYAFrom VIDYALAYA the Principal’s EOI, DeskKATHMANDU “Excellence is an art won by training and habituation”-Aristotle VIDYALAYA PATRIKA 2019-20 ( 8 ) KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA EOI, KATHMANDU Editorial... If your world looks gloomy and you are feeling grin and glum, Make a rainbow for yourself, Don't wait for one to come, Don't sit watching at the window for the clouds to part There'll soon be a rainbow if you start one in your heart. We are really proud and exuberant to acclaim that we are ready with all new hopes and hues to bring out this E-magazine, which will surely unfold the unravelled world of the most unforgettable and precious moments of the vidyalaya. -

Samaj Laghubitta Bittiya Sanstha Ltd. Demat Shareholder List S.N

SAMAJ LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA SANSTHA LTD. DEMAT SHAREHOLDER LIST S.N. BOID Name Father Name Grandfather Name Total Kitta Signature 1 1301010000002317 SHYAM KRISHNA NAPIT BHUYU LAL NAPIT BHU LAL NAPIT / LAXMI SHAKYA NAPIT 10 2 1301010000004732 TIKA BAHADUR SANJEL LILA NATHA SANJEL DUKU PD SANJEL / BIMALA SANJEL 10 3 1301010000006058 BINDU POKHAREL WASTI MOHAN POKHAREL PURUSOTTAM POKHAREL/YADAB PRASAD WASTI 10 4 1301010000006818 REJIKA SHAKYA DAMODAR SHAKYA CHANDRA BAHADUR SHAKYA 10 5 1301010000006856 NIRMALA SHRESTHA KHADGA BAHADUR SHRESTHA LAL BAHADUR SHRESTHA 10 6 1301010000007300 SARSWATI SHRESTHA DHUNDI BHAKTA RAJLAWAT HARI PRASAD RAJLAWAT/SAROJ SHRESTHA 10 7 1301010000010476 GITA UPADHAYA SHOVA KANTA GNAWALI NANDA RAM GNAWALI 10 8 1301010000011636 SHUBHASINNI DONGOL SURYAMAN CHAKRADHAR SABIN DONGOL/RUDRAMAN CHAKRADHAR 10 9 1301010000011898 HARI PRASAD ADHIKARI JANAKI DATTA ADHIKARI SOBITA ADHIKARI/SHREELAL ADHIKARI 10 10 1301010000014850 BISHAL CHANDRA GAUTAM ISHWAR CHANDRA GAUTAM SAMJHANA GAUTAM/ GOVINDA CHANDRA GAUTAM 10 11 1301010000018120 KOPILA DHUNGANA GHIMIRE LILAM BAHADUR DHUNGANA BADRI KUMAR GHIMIRE/ JAGAT BAHADUR DHUNGANA10 12 1301010000019274 PUNESHWORI CHAU PRADHAN RAM KRISHNA CHAU PRADHAN JAYA JANMA NAKARMI 10 13 1301010000020431 SARASWATI THAPA CHITRA BAHADUR THAPA BIRKHA BAHADUR THAPA 10 14 1301010000022650 RAJMAN SHRESTHA LAXMI RAJ SHRESTHA RINA SHRESTHA/ DHARMA RAJ SHRESTHA 10 15 1301010000022967 USHA PANDEY BHAWANI PANDEY SHYAM PRASAD PANDEY 10 16 1301010000023956 JANUKA ADHIKARI DEVI PRASAD NEPAL SUDARSHANA ADHIKARI -

The Guthi System of Nepal

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 The Guthi System of Nepal Tucker Scott SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, Civic and Community Engagement Commons, East Asian Languages and Societies Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Scott, Tucker, "The Guthi System of Nepal" (2019). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 3182. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/3182 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Guthi System of Nepal Tucker Scott Academic Director: Suman Pant Advisors: Suman Pant, Manohari Upadhyaya Vanderbilt University Public Policy Studies South Asia, Nepal, Kathmandu Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Nepal: Development and Social Change, SIT Study Abroad Spring 2019 and in fulfillment of the Capstone requirement for the Vanderbilt Public Policy Studies Major Abstract The purpose of this research is to understand the role of the guthi system in Nepali society, the relationship of the guthi land tenure system with Newari guthi, and the effect of modern society and technology on the ability of the guthi system to maintain and preserve tangible and intangible cultural heritage in Nepal. -

NEWAR ARCHITECTURE the Typology of the Malla Period Monuments of the Kathmandu Valley

BBarbaraarbara Gmińska-NowakGmińska-Nowak Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Polish Institute of World Art Studies NEWAR ARCHITECTURE The typology of the Malla period monuments of the Kathmandu Valley INTRODUCTION: NEPAL AND THE KATHMANDU VALLEY epal is a country with an old culture steeped in deeply ingrained tradi- tion. Political, trade and dynastic relations with both neighbours – NIndia and Tibet, have been intense for hundreds of years. The most important of the smaller states existing in the current territorial borders of Nepal is that of the Kathmandu Valley. This valley has been one of the most important points on the main trade route between India and Tibet. Until the late 18t century, the wealth of the Kathmandu Valley reflected in the golden roofs of numerous temples and the monastic structures adorned by artistic bronze and stone sculptures, woodcarving and paintings was mainly gained from commerce. Being the point of intersection of significant trans-Himalaya trade routes, the Kathmandu Valley was a centre for cultural exchange and a place often frequented by Hindu and Buddhist teachers, scientists, poets, architects and sculptors.1) The Kathmandu Valley with its main cities of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhak- tapur is situated in the northeast of Nepal at an average height of 1350 metres above sea level. Today it is still the administrative, cultural and historical centre of Nepal. South of the valley lies a mountain range of moderate height whereas the lofty peaks of the Himalayas are visible in the North. 1) Dębicki (1981: 11 – 14). 10 Barbara Gmińska-Nowak The main group of inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley are the Newars, an ancient and high organised ethnic group very conscious of its identity. -

Swarthmore College Bal Gopal Shrestha. 2015. the Newars of Sikkim

BOOK REVIEWS | 439 of engrossing quality that listening to your grandfather fondly reminisce about his life does. Students and acquaintances of Baral will definitely find a great deal to appreciate in his autobiography, and for other people, it is a sometimes exhausting but ultimately rewarding read. Abha Lal Swarthmore College Bal Gopal Shrestha. 2015. The Newars of Sikkim: Reinventing Language, Culture, and Identity in the Diaspora. Kathmandu: Vajra Books. This ethnographical work is by far the most comprehensive account of the Newars in the diaspora. Based on the fieldwork among the Newars in Sikkim, it argues that power politics compels the subjects to expand the networks of relation and power to adjust in the alien culture. Then they seek to connect to their home tradition and language. Shrestha has published widely on the Nepali religious rituals, Hinduism, Buddhism, ethnic nationalism, and the Maoist movement. His previous book The Sacred Town of Sankhu: The Anthropology of Newar Ritual, Religion and Sankhu in Nepal (2012) was an ethnographic account of the Newars in their homeland. In this book, Shrestha studies the restructuring of the ethnic identity in the diaspora. He considers ritual practice – for the Newars, the guñhãs (especially the traditional funeral association, si: guthi:) – as a marker of such identity. Based on the finding that this practice has been abandoned by the Newars in Sikkim, he raises the following questions: How do ritual traditions function in a new historical and social context? How are rituals invented under altered circumstances? What is identity constructed through transnational linkages over long distances? On the theoretical level, Shrestha attempts to satisfy nine major features of Diaspora proposed in Robin Cohen’s Global Diaspora: An Introduction (1997: 180) by taking the legendary Laxmi Das Kasaju, who left Nepal (feature a) to save his life after the rise of Jangabahadur Rana in 1846. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

SANA GUTHI and the NEWARS: Impacts Of

SANA GUTHI AND THE NEWARS: Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Social Organizations Niraj Dangol Thesis Submitted for the Degree: Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education University of Tromsø Norway Autumn 2010 SANA GUTHI AND THE NEWARS: Impacts of Modernization on Traditional Social Organizations By Niraj Dangol Thesis Submitted for the Degree: Master of Philosophy in Indigenous Studies Faculty of Social Science, University of Tromsø Norway Autumn 2010 Supervised By Associate Professor Bjørn Bjerkli i DEDICATED TO ALL THE NEWARS “Newa: Jhi Newa: he Jui” We Newars, will always be Newars ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I regard myself fortunate for getting an opportunity to involve myself as a student of University of Tromsø. Special Thanks goes to the Sami Center for introducing the MIS program which enables the students to gain knowledge on the issues of Indigeneity and the Indigenous Peoples. I would like to express my grateful appreciation to my Supervisor, Associate Prof. Bjørn Bjerkli , for his valuable supervision and advisory role during the study. His remarkable comments and recommendations proved to be supportive for the improvisation of this study. I shall be thankful to my Father, Mr. Jitlal Dangol , for his continuous support and help throughout my thesis period. He was the one who, despite of his busy schedules, collected the supplementary materials in Kathmandu while I was writing this thesis in Tromsø. I shall be thankful to my entire family, my mother and my sisters as well, for their continuous moral support. Additionally, I thank my fiancé, Neeta Maharjan , who spent hours on internet for making valuable comments on the texts and all the suggestions and corrections on the chapters. -

Unclaimed Dividend List Upto Ashad 2077

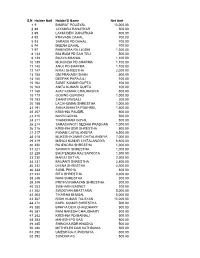

S.N Holder No# Holder'S Name Net Amt 1 9 BHARAT POUDYAL 10,000.00 2 88 JAYAMBU RANJITKAR 500.00 3 89 LAXMI DEVI RANJITKAR 500.00 4 92 PRAVASH DAHAL 700.00 5 93 SARADA PD DAHAL 700.00 6 94 MEENA DAHAL 700.00 7 97 RABINDRA RAJ JOSHI 1,300.00 8 133 BALIRAM PD SAH TELI 500.00 9 138 BIJAYA KHANAL 1,100.00 10 139 MUKUNDA PD SHARMA 1,100.00 11 140 ANUJ PD SHARMA 1,100.00 12 147 NIRAJ SHRESTHA 2,000.00 13 155 OM PRAKASH SHAH 500.00 14 160 DEEPAK PARAJULI 100.00 15 162 SUMIT KUMAR GUPTA 100.00 16 163 ANITA KUMARI GUPTA 100.00 17 165 AJAY KUMAR CHAURASIYA 500.00 18 173 GOBIND GURUNG 1,000.00 19 183 SHANTI RASAILI 200.00 20 188 LACHHUMAN SHRESTHA 1,000.00 21 191 SHIVA BHAKTA POKHREL 1,500.00 22 207 KRISHNA PAUDEL 500.00 23 210 NAVIN GOYAL 500.00 24 211 THANDIRAM GOYAL 500.00 25 214 SARASHWOTI SEDHAI PRADHAN 1,000.00 26 216 KRISHNA BDR SHRESTHA 500.00 27 217 PUNAM CHITALANGIYA 6,500.00 28 218 MUKESH KUMAR CHITALANGIYA 7,000.00 29 219 MANOJ KUMAR CHITALANGIYA 6,500.00 30 220 RAJENDRA SHRESTHA 1,000.00 31 221 SWIKRITI SHRESTHA 1,000.00 32 229 BHUPENDRA RAJ SAPKOTA 1,500.00 33 230 MANJU SATYAL 2,000.00 34 231 BAIJANTI SHRESTHA 2,800.00 35 232 LEENA SHRESTHA 3,300.00 36 233 SUNIL PIKHA 600.00 37 234 RITA SHRESTHA 3,300.00 38 248 NANI SHRESTHA 300.00 39 249 PRITHVI NARAYAN SHRESTHA 300.00 40 253 SUBHASH BASNET 100.00 41 262 SWOGYAN BHATTARAI 5,000.00 42 263 TIKARAM BHUSAL 5,000.00 43 267 RISHI KUMAR TULSYAN 10,000.00 44 272 KAPIL KUMAR SHRESTHA 500.00 45 280 BINAYA DEVI CHAUDHARY 500.00 46 281 RAM NARESH CHAUDHARY 500.00 47 282 KRISHNA PD MAINALI 500.00 -

Bhaktapur, Nepal's Cow Procession and the Improvisation of Tradition

FORGING SPACE: BHAKTAPUR, NEPAL’S COW PROCESSION AND THE IMPROVISATION OF TRADITION By: GREGORY PRICE GRIEVE Grieve, Gregory P. ―Forging a Mandalic Space: Bhaktapur, Nepal‘s Cow Procession and the Improvisation of Tradition,‖ Numen 51 (2004): 468-512. Made available courtesy of Brill Academic Publishers: http://www.brill.nl/nu ***Note: Figures may be missing from this format of the document Abstract: In 1995, as part of Bhaktapur, Nepal‘s Cow Procession, the new suburban neighborhood of Suryavinayak celebrated a ―forged‖ goat sacrifice. Forged religious practices seem enigmatic if one assumes that traditional practice consists only of the blind imitation of timeless structure. Yet, the sacrifice was not mechanical repetition; it could not be, because it was the first and only time it was celebrated. Rather, the religious performance was a conscious manipulation of available ―traditional‖ cultural logics that were strategically utilized during the Cow Procession‘s loose carnivalesque atmosphere to solve a contemporary problem—what can one do when one lives beyond the borders of religiously organized cities such as Bhaktapur? This paper argues that the ―forged‖ sacrifice was a means for this new neighborhood to operate together and improvise new mandalic space beyond the city‘s traditional cultic territory. Article: [E]very field anthropologist knows that no performance of a rite, however rigidly prescribed, is exactly the same as another performance.... Variable components make flexible the basic core of most rituals. ~Tambiah 1979:115 In Bhaktapur, Nepal around 5.30 P.M. on August 19, 1995, a castrated male goat was sacrificed to Suryavinayak, the local form of the god Ganesha.1 As part of the city‘s Cow Procession (nb.