Cialis Discount

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWAR ARCHITECTURE the Typology of the Malla Period Monuments of the Kathmandu Valley

BBarbaraarbara Gmińska-NowakGmińska-Nowak Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Polish Institute of World Art Studies NEWAR ARCHITECTURE The typology of the Malla period monuments of the Kathmandu Valley INTRODUCTION: NEPAL AND THE KATHMANDU VALLEY epal is a country with an old culture steeped in deeply ingrained tradi- tion. Political, trade and dynastic relations with both neighbours – NIndia and Tibet, have been intense for hundreds of years. The most important of the smaller states existing in the current territorial borders of Nepal is that of the Kathmandu Valley. This valley has been one of the most important points on the main trade route between India and Tibet. Until the late 18t century, the wealth of the Kathmandu Valley reflected in the golden roofs of numerous temples and the monastic structures adorned by artistic bronze and stone sculptures, woodcarving and paintings was mainly gained from commerce. Being the point of intersection of significant trans-Himalaya trade routes, the Kathmandu Valley was a centre for cultural exchange and a place often frequented by Hindu and Buddhist teachers, scientists, poets, architects and sculptors.1) The Kathmandu Valley with its main cities of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhak- tapur is situated in the northeast of Nepal at an average height of 1350 metres above sea level. Today it is still the administrative, cultural and historical centre of Nepal. South of the valley lies a mountain range of moderate height whereas the lofty peaks of the Himalayas are visible in the North. 1) Dębicki (1981: 11 – 14). 10 Barbara Gmińska-Nowak The main group of inhabitants of the Kathmandu Valley are the Newars, an ancient and high organised ethnic group very conscious of its identity. -

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: a Newar Perspective

Language Politics and State Policy in Nepal: A Newar Perspective A Dissertation Submitted to the University of Tsukuba In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Public Policy Suwarn VAJRACHARYA 2014 To my mother, who taught me the value in a mother tongue and my father, who shared the virtue of empathy. ii Map-1: Original Nepal (Constituted of 12 districts) and Present Nepal iii Map-2: Nepal Mandala (Original Nepal demarcated by Mandalas) iv Map-3: Gorkha Nepal Expansion (1795-1816) v Map-4: Present Nepal by Ecological Zones (Mountain, Hill and Tarai zones) vi Map-5: Nepal by Language Families vii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents viii List of Maps and Tables xiv Acknowledgements xv Acronyms and Abbreviations xix INTRODUCTION Research Objectives 1 Research Background 2 Research Questions 5 Research Methodology 5 Significance of the Study 6 Organization of Study 7 PART I NATIONALISM AND LANGUAGE POLITICS: VICTIMS OF HISTORY 10 CHAPTER ONE NEPAL: A REFLECTION OF UNITY IN DIVERSITY 1.1. Topography: A Unique Variety 11 1.2. Cultural Pluralism 13 1.3. Religiousness of People and the State 16 1.4. Linguistic Reality, ‘Official’ and ‘National’ Languages 17 CHAPTER TWO THE NEWAR: AN ACCOUNT OF AUTHORS & VICTIMS OF THEIR HISTORY 2.1. The Newar as Authors of their history 24 2.1.1. Definition of Nepal and Newar 25 2.1.2. Nepal Mandala and Nepal 27 Territory of Nepal Mandala 28 viii 2.1.3. The Newar as a Nation: Conglomeration of Diverse People 29 2.1.4. -

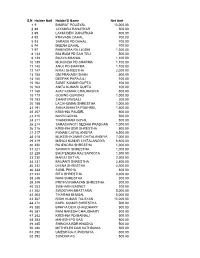

Unclaimed Dividend List Upto Ashad 2077

S.N Holder No# Holder'S Name Net Amt 1 9 BHARAT POUDYAL 10,000.00 2 88 JAYAMBU RANJITKAR 500.00 3 89 LAXMI DEVI RANJITKAR 500.00 4 92 PRAVASH DAHAL 700.00 5 93 SARADA PD DAHAL 700.00 6 94 MEENA DAHAL 700.00 7 97 RABINDRA RAJ JOSHI 1,300.00 8 133 BALIRAM PD SAH TELI 500.00 9 138 BIJAYA KHANAL 1,100.00 10 139 MUKUNDA PD SHARMA 1,100.00 11 140 ANUJ PD SHARMA 1,100.00 12 147 NIRAJ SHRESTHA 2,000.00 13 155 OM PRAKASH SHAH 500.00 14 160 DEEPAK PARAJULI 100.00 15 162 SUMIT KUMAR GUPTA 100.00 16 163 ANITA KUMARI GUPTA 100.00 17 165 AJAY KUMAR CHAURASIYA 500.00 18 173 GOBIND GURUNG 1,000.00 19 183 SHANTI RASAILI 200.00 20 188 LACHHUMAN SHRESTHA 1,000.00 21 191 SHIVA BHAKTA POKHREL 1,500.00 22 207 KRISHNA PAUDEL 500.00 23 210 NAVIN GOYAL 500.00 24 211 THANDIRAM GOYAL 500.00 25 214 SARASHWOTI SEDHAI PRADHAN 1,000.00 26 216 KRISHNA BDR SHRESTHA 500.00 27 217 PUNAM CHITALANGIYA 6,500.00 28 218 MUKESH KUMAR CHITALANGIYA 7,000.00 29 219 MANOJ KUMAR CHITALANGIYA 6,500.00 30 220 RAJENDRA SHRESTHA 1,000.00 31 221 SWIKRITI SHRESTHA 1,000.00 32 229 BHUPENDRA RAJ SAPKOTA 1,500.00 33 230 MANJU SATYAL 2,000.00 34 231 BAIJANTI SHRESTHA 2,800.00 35 232 LEENA SHRESTHA 3,300.00 36 233 SUNIL PIKHA 600.00 37 234 RITA SHRESTHA 3,300.00 38 248 NANI SHRESTHA 300.00 39 249 PRITHVI NARAYAN SHRESTHA 300.00 40 253 SUBHASH BASNET 100.00 41 262 SWOGYAN BHATTARAI 5,000.00 42 263 TIKARAM BHUSAL 5,000.00 43 267 RISHI KUMAR TULSYAN 10,000.00 44 272 KAPIL KUMAR SHRESTHA 500.00 45 280 BINAYA DEVI CHAUDHARY 500.00 46 281 RAM NARESH CHAUDHARY 500.00 47 282 KRISHNA PD MAINALI 500.00 -

Sculptures of Kamakhya Temple: an Aesthetic View

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 3, Issue 10, October 2013 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Sculptures of Kamakhya Temple: An Aesthetic View Mousumi Deka Research Scholar, Department of Visual Arts, Assam University, Silchar Abstract- The Kamakhya temple is one of the world known religious centre. Though, the temple is regarded as the great religious Tantriccentre but, it lays great emphasis on the sculptural art. The temple exits at the Nilachal hill of Assam. The myth, religion and art are amalgamated in the Kamakhya temple. The reconstructed temple shows the sculptural art of different times. Numerous sculptural images are very similar to the Gupta art style. The study focuses upon the characteristics of the stone images and traces the myth behind the temple. The stone images are analyzed according to the subject matter. Index Terms- Aesthetic, Kamakhya temple, Myth, Sculptures I. Section I he Kamakhya temple is one of the main pithas (sacred place) among fifty oneSaktipithas and the temple is dedicated to Mother T Goddess Kamakhya. Kamakhya is another form of Goddess Parvati. The Kamakhya temple is located on the Nilachal hill in western part of Guwahati city in Assam. There is an incomplete stone staircase known as the Mekhalaujua path along with the Kamakhya temple. Mother Goddess Kamakhya is worshiped here in the „Yoni’ (genitalia)form. The most celebrated festival is the Ambubachi festival. It is widely believed that during the period of festival of each summer, Devi Kamakhya goes through her menstrual cycle. The history was silent that when the temple was originally built. But, it was estimated that the temple was built around the 4th -5th century A D. -

Community Based Participatory Approach in Cultural Heritage Reconstruction: a Case Study of Kasthamandap

Community based participatory approach in Cultural Heritage Reconstruction: A case study of Kasthamandap Rija Joshi1, Alina Tamrakar2, Binita Magaiya3 Abstract Kasthamandap, a centrally located monument in the old settlement of Kathmandu, is the 7th century structure, from which the name of Kathmandu valley originated. Kasthamandap was originally a public rest house and holds social, cultural and religious significance. The 25th April Gorkha earthquake completely collapsed the monument and it took a year before the government disclosed its reconstruction plan. However, the preparations were not satisfactory. The proposed plans severely contradicted with the traditional construction system. The introduction of modern materials such as steel and concrete made the aesthetic and artistic values of the monument to lose its original identity. The general public couldn’t accommodate with the idea of our national heritage being rebuilt with considerably newer materialistic ideas and a large public outcry against the proposal was seen. The necessity of reconstruction using traditional methods and materials with equal involvement of the community was realised to maintain identity, increase community belongingness and to connect new generation with the heritage. Therefore, a community initiative to rebuild Kasthamandap started with the involvement of diverse groups from the community. This paper discusses the observations, learning and achievements of community participation of the Kasthamandap rebuilding process. Further, the paper includes exploration of both tangible and intangible aspect and its benefits for overall heritage knowledge of Kathmandu valley. This paper presents an exemplary participatory heritage-making concept, which can be a learning for heritage reconstructions in future. Key words: Cultural Heritage, Community participation, Reconstruction, Conservation 1. -

Ritual Movement in the City of Lalitpur

RITUAL MOVEMENT IN THE CITY OF LALITPUR Mark A. Pickett This article intends to explore the ways that the symbolic organization of space in the Newar city of Lalitpur (J;'atan) is renewed through ritualized movement in the many processions that take place throughout the year. Niels GUlschow (1982: 190-3) has done much 10 delineate the various processions and has constructed a typology of fOUf different forms, I In my analysis I build on this work and propose a somewhat morc sophisticated typology of processions that differentiates the lypes still further. Sets of Deities Space is defined by reference to several sels of deities that are positioned at significant locations in and around the city. Gutschow (ibid.: 165, Map [82) shows a set of four Bhimsen shrines and four Narayana shrines which are all located within the city. 80th sets of four ~hrines encircle the central palace area. Gutschow (ibid.: 65, Map 183) also shows the locations of eight Ganesh shrines that are divided into two sets of four. One of these groups describes a polygon that like those of the shrines of Bhimsen and Narayana, encircles the palace area. It is not clear what significance, if any, that these particular sets of deities have for the life of the city. They do not givc risc to any specific festival, nor are they visited, as far as I am aware in any consecutive manncr. Other sets of deities have very clear meaning, however, and it is to thesc that I shall now turn to first morc on the boundaries which give the city much of its character. -

MAHALAXMI 2056/2057DIVIDEND SN S.HOLDER Name of Share Holder Cash 1 24 Kanti Devi Nunia 168 2 70 Bharat Pd Khanal 56 3 114 Hari

MAHALAXMI 2056/2057DIVIDEND SN S.HOLDER Name Of Share Holder Cash 1 24 kanti devi nunia 168 2 70 bharat pd khanal 56 3 114 hari pd paudel 56 4 204 bhagya narayan misra 56 5 205 awaadh kishor pd rauniyar 112 6 237 ramesh k agrawal 112 7 247 janaki shrestha rawal 56 8 256 sandip man sakya 56 9 275 ramesh pd shah 140 10 276 roshan k shah 140 11 303 tilak lal shrestha 140 12 310 laxmi devi shrestha 140 13 326 sarita devi rauniyar 168 14 482 sarba jit lal pd kalwar 140 15 483 ishwari lal pd 140 16 507 bimala devi 140 17 514 prem lata kumari 140 18 521 binod kumar agrawal 168 19 522 ramesh k agrawal 196 20 523 paban kaagrawal 28 21 537 jwala pd raghubansi 56 22 547 krishna lal sah teli 56 23 555 naresh k paudel 56 24 609 govenda man dandol 56 25 704 ram ayodya pd 84 26 705 kamala kanta devi 84 27 706 arjun kumar abinas 56 28 708 nabin sharma 56 29 807 prava devi dangol 56 30 857 sanjay kumar shrestha 56 31 899 mahesh pd gupta 56 32 900 sudama devi 56 33 902 dipak k agawal 140 34 921 laxmi manandhar 84 35 933 raj kisor pd kalwar 56 36 969 aakash kumar rauniyar 168 37 970 aasish kumar rauniyar 168 38 971 dinesh pd rauniyar 168 39 972 atul kumar rauniyar 168 40 973 sobha devi 56 41 991 kamarudin miya 56 42 1021 purna chandra bhattarai 56 43 1044 ganesh kumari ranjitkar 56 44 1055 nati kaji shakya 56 45 1137 bhai ram ranjit 112 46 1159 suryaman maharjan kulai 140 47 1161 tanka raj pokhrel 28 48 1235 bidhya maharjan 56 49 1236 bibek maharjan 56 50 1237 rakshya maharjan 56 51 1238 chiri babu maharjan 140 52 1239 misri maharjan 140 53 1240 babu kaji -

State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 (MRG)

State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 Events of 2015 Focus on culture and heritage State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 20161 Events of 2015 Front cover: Cholitas, indigenous Bolivian Focus on culture and heritage women, dancing on the streets of La Paz as part of a fiesta celebrating Mother’s Day. REUTERS/ David Mercado. Inside front cover: Street theatre performance in the Dominican Republic. From 2013 to 2016 MRG ran a street theatre programme to challenge discrimination against Dominicans of Haitian Descent in the Acknowledgements Dominican Republic. MUDHA. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) Inside back cover: Maasai community members in gratefully acknowledges the support of all Kenya. MRG. organizations and individuals who gave financial and other assistance to this publication, including the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. © Minority Rights Group International, July 2016. All rights reserved. Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non-commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for Support our work commercial purposes without the prior express Donate at www.minorityrights.org/donate permission of the copyright holders. MRG relies on the generous support of institutions and individuals to help us secure the rights of For further information please contact MRG. A CIP minorities and indigenous peoples around the catalogue record of this publication is available from world. All donations received contribute directly to the British Library. our projects with minorities and indigenous peoples. ISBN 978-1-907919-80-0 Subscribe to our publications at State of www.minorityrights.org/publications Published: July 2016 Another valuable way to support us is to subscribe Lead reviewer: Carl Soderbergh to our publications, which offer a compelling Production: Jasmin Qureshi analysis of minority and indigenous issues and theWorld’s Copy editing: Sophie Richmond original research. -

Sapta Matrikas in Indian Art and Their Significance in Indian Sculpture and Ethos: a Critical Study

Anistoriton, vol. 9, March 2005, section A051 1 SAPTA MATRIKAS IN INDIAN ART AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE IN INDIAN SCULPTURE AND ETHOS: A CRITICAL STUDY Meghali Goswami, Dr.Ila Gupta, Dr.P.Jha Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee, INDIA This paper focuses on the study of ancient Indian sculptures of seven mother goddesses called Sapta Matrikas, and brings out their distinctive features as conceived by the master sculptures of different periods. It also explains their importance in Indian art and cultural ethos. Introduction The seven mother goddesses are: Brahamani, Vaishnavi, Maheshwari, Kaumari, Varahi, Indrani and Chamunda.Their description in ancient Puranas, such as Varaha Purana, Matsya Purana, Markandeya Purana etc refers to their antiquity. Each of the mother goddesses (except for Chamunda) had come to take her name from a particular God: Brahamani form Brahma, Vaishnavi from Vishnu, Maheswari from Shiva, Kaumari from Skanda, Varahi from Varaha and Indrani from Indra1.They are armed with the same weapons,wears the same ornaments and rides the same vahanas and also carries the same banners like their corresponding male Gods do. The earliest reference of Sapta Matrika is found in Markandeya Purana and V.S Agarwalla dates it to 400 A.D to 600 A.D Mythology There are different Puranic versions related to the origin of Matrikas. According to Puranic myths Matrikas are Shakti of Shiva,Indra and other gods and they are goddesses of the battlefield. But in the sculptural portrayals, they are depicted differently as benevolent, compassionate and aristocratic mothers. It is said that the Sapta-Matrikas are connected with Shiva. -

Early Medieval Representation of Human Anatomy: a Case Study of Chamunda Stone Image from Dharamsala, Odisha

Early Medieval Representation of Human Anatomy: A Case Study of Chamunda Stone Image from Dharamsala, Odisha Rushal Unkule1, Gopal Joge1 and Veena Mushrif‐Tripathy1 1. Department of Ancient Indian History, Culture and Archaeology, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Deemed to be University, Pune – 411 006, Maharashtra, India (Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) Received: 17October 2017; Revised: 10November 2017; Accepted: 13 December 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 191‐200 Abstract: The understanding of the human anatomy was a subject of an investigation of various civilizations for the purpose of varied reasons. However, in Indian tradition, it is often seen and discussed taking into consideration its religious background, and to some extent, it was a subject of magico‐ medicinal studies. Whereas, this traditional understanding of human anatomy is seen in various types of visuals since Early Historic period. In which most fascinating portrayal of human anatomy is noticed on stone sculptures. Especially, the Early Medieval depictions of some Brahmanical deities began to show with its anatomical details, in which the representation of goddess Chamunda took an important place where her skeletal features developed had become an identical norm. While making an image of Chamunda with all its anatomical details the sculptor requires the basic knowledge of the human anatomy. This knowledge may have been gained by these sculptors through the observation of actual human anatomy to achieve the certain perfection. This artistic perfection can be seen resulted in some of the sculptures found different parts of the country. However, such types of several stone images of Chamunda with its micro anatomical details are often noticed in the state of Odisha, which once was the primecenter of Shaktism. -

Essence of Hindu Festivals & Austerities

ESSENCE OF HINDU FESTIVALS AND AUSTERITIES Edited and translated by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager of India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi now at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:- Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras* Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana*- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra Essence Neeti Chandrika* [Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. Kamakoti. Org/news as also on Google by the respective references. The one with * is under process] 2 PREFACE Dharma and Adharma are the two wheels of Life‟s Chariot pulling against each other. -

No Justice, No Peace: Conflict, Socio-Economic Rights, and the New Constitution in Nepal

WICKERI_FINAL_051710_KPF (DO NOT DELETE) 5/21/2010 1:20:10 AM NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE: CONFLICT, SOCIO-ECONOMIC RIGHTS, AND THE NEW CONSTITUTION IN NEPAL Elisabeth Wickeri* I. INTRODUCTION One day after the signing of the November 21, 2006 Com- prehensive Peace Accord (CPA) between the Nepali govern- ment1 and the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), Kath- mandu’s The Himalayan Times editorial board declared, “Nepal has entered into a new era of peace, democracy and govern- ance.”2 The CPA formally ended the more than ten-year con- flict waged by Maoist insurgents since 1996.3 Over the next * Executive Director, Leitner Center for International Law and Justice at Fordham Law School, 2009–Present; Fellow, Joseph R. Crowley Program in International Human Rights, Leitner Center for International Law and Justice, 2008–2010; J.D., New York University School of Law, 2004; B.A., Smith College, 2000. Empirical research for this Article is drawn in part on field- work the author led in Nepal in March and May 2009 as part of the Fordham Law School Crowley Program in International Human Rights. The 2009 program focused on land rights in rural, southwestern Nepal. Participants conducted interviews with more than four hundred people in fifteen communities in southern Nepal, as well as local and national government representatives, activists, civil society workers, and international actors. Additional inter- views were conducted in March 2010. This documentation of the impact of landlessness on the rights of rural Nepalis forms the basis of the author’s analysis of the state of socio- economic rights guarantees in Nepal today.