Hauntology Beyond the Cinema: the Technological Uncanny 66 Closings 78 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Read a PDF Version of This Media Release, Click Here

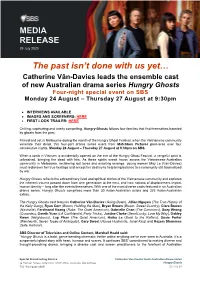

MEDIA RELEASE 29 July 2020 The past isn’t done with us yet… Catherine Văn-Davies leads the ensemble cast of new Australian drama series Hungry Ghosts Four-night special event on SBS Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm • INTERVIEWS AVAILABLE • IMAGES AND SCREENERS: HERE • FIRST LOOK TRAILER: HERE Chilling, captivating and utterly compelling, Hungry Ghosts follows four families that find themselves haunted by ghosts from the past. Filmed and set in Melbourne during the month of the Hungry Ghost Festival, when the Vietnamese community venerate their dead, this four-part drama series event from Matchbox Pictures premieres over four consecutive nights, Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm on SBS. When a tomb in Vietnam is accidentally opened on the eve of the Hungry Ghost Festival, a vengeful spirit is unleashed, bringing the dead with him. As these spirits wreak havoc across the Vietnamese-Australian community in Melbourne, reclaiming lost loves and exacting revenge, young woman May Le (Văn-Davies) must rediscover her true heritage and accept her destiny to help bring balance to a community still traumatised by war. Hungry Ghosts reflects the extraordinary lived and spiritual stories of the Vietnamese community and explores the inherent trauma passed down from one generation to the next, and how notions of displacement impact human identity – long after the events themselves. With one of the most diverse casts featured in an Australian drama series, Hungry Ghosts comprises more than 30 Asian-Australian actors and 325 -

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

Co-Produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the Vision

Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the vision. the voice. From LA to London and Martinique to Mali. We bring you the world ofBlack film. Ifyou're concerned about Black images in commercial film and tele vision, you already know that Hollywood does not reflect the multi- cultural nature 'ofcontemporary society. You know thatwhen Blacks are not absent they are confined to predictable, one-dimensional roles. You may argue that movies and television shape our reality or that they simply reflect that reality. In any case, no one can deny the need to take a closer look atwhat is COIning out of this powerful medium. Black Film Review is the forum you've been looking for. Four times a year, we bringyou film criticiSIn froIn a Black perspective. We look behind the surface and challenge ordinary assurnptiorls about the Black image. We feature actors all.d actresses th t go agaul.st the graill., all.d we fill you Ul. Oll. the rich history ofBlacks Ul. Arnericall. filrnrnakul.g - a history thatgoes back to 19101 And, Black Film Review is the only magazine that bringsyou news, reviews and in-deptll interviews frOtn tlle tnost vibrant tnovetnent in contelllporary film. You know about Spike Lee butwIlat about EuzIlan Palcy or lsaacJulien? Souletnayne Cisse or CIl.arles Burnette? Tllrougll out tIle African cliaspora, Black fi1rnInakers are giving us alternatives to tlle static itnages tIlat are proeluceel in Hollywood anel giving birtll to a wIlole new cinetna...be tIlere! Interview:- ----------- --- - - - - - - 4 VDL.G NO.2 by Pat Aufderheide Malian filmmaker Cheikh Oumar Sissoko discusses his latest film, Finzan, aself conscious experiment in storytelling 2 2 E e Street, NW as ing on, DC 20006 MO· BETTER BLUES 2 2 466-2753 The Music 6 o by Eugene Holley, Jr. -

Dead Season1

158 Dead Season1 Caroline Sy HAU Professor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University In Kyoto, the Obon festival in honor of the spirits of ancestors falls around the middle of August. The day of the festival varies according to region and the type of calendar (solar or lunar) used. The Kanto region, including Tokyo, observes Obon in mid-July, while northern Kanto, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Okinawa celebrate their Old Bon (Kyu Bon) on the 15th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar. For most Japanese, though, August, shimmering Nilotic August, is dead season. Children have their school break, Parliament is not in session, and as many who can afford it go abroad. Because Kyoto sits in a valley, daytime temperature can run up to the mid- and even upper 30s. Obon is not a public holiday, but people often take leave to return to their ancestral hometowns to visit and clean the family burial grounds. The Bon Odori dance is based on the story of the monk Mokuren, who on Buddha’s advice was able to ease the suffering of his dead mother and who was said to have danced for joy at her release. The festival culminates in paper lanterns being floated across rivers and in dazzling displays of fireworks. An added attraction in Kyoto is the Daimonji festival held on August 16. Between 8:00 and 8:20 p.m., fires in the shape of the characters “great” (dai, ) and “wondrous dharma” (myo/ho ) and in the shapes of a boat and a torii gate are lit in succession on five mountains encircling the city. -

Cinema and New Technologies: the Development of Digital

CINEMA AND NEW TECHNOLOGIES: THE DEVELOPMENT OF DIGITAL VIDEO FILMMAKING IN WEST AFRICA S. BENAGR Ph.D 2012 UNIVERSITY OF BEDFORDSHIRE CINEMA AND NEW TECHNOLOGIES: THE DEVELOPMENT OF DIGITAL VIDEO FILMMAKING IN WEST AFRICA by S. BENAGR A thesis submitted to the University of Bedfordshire in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2012 2 Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................. 5 LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................ 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ...................................................................................... 7 DEDICATION: ....................................................................................................... 8 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ................................................ 9 ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................... 13 Chapter One: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Key Questions of the Research ................................................................... 14 1.2 Methodologies ............................................................................................. 21 1.3 Context: Ghana and Burkina Faso .............................................................. 28 1.4 Context: Development of Film Cultures .................................................... -

Lacrimosa Dr

Juli / August 14 AusgAbe 37 - JAhrgAng 7 Deine Lakaien LacrimoSa Dr. mark benecke Letzte inStanz opeth grA mitnehmen entombeD a.D. tis zum otto Dix SubStaat 2 eDitoriaL inhaLt Hoherlehmer Straße 5 – 15738 Zeuthen Tel. 03376/2462946 www.negatief.de Nach zweijähriger Absenz wagten wir mit der letz- 31 Ankh ten Ausgabe den Sprung ins kalte Wasser und be- 8 Astari Nite Herausgeber, Vertrieb & V.i.S.d.P.: lebten das NEGAtief neu. Viel Arbeit und Idealismus 5 CD-Tipps Bruno Kramm ([email protected]) sind in das Heft geflossen und umso erfreuter waren 6 Deine Lakaien Chefredaktion & Redaktionsleitung: wir über die positiven Resonanzen, die wir auf Face- Sascha Blach ([email protected]) book, in den Clubs, von Labels und Bands und vor 15 Digitalis Purpurea Marketing: Johannes Thon ([email protected]) allem beim Wave Gotik Treffen in Leipzig bekommen 24 Entombed A.D. Marketing Multimedia: Yvonne Brasseur 10 Lacrimosa ([email protected]) haben. Vier Tage lang stand unser eifriges Team dort Layout: Miriam Barth ([email protected]) in der Agra-Halle am NEGAtief-Stand und sorgte da- 7 Letzte Instanz Internet: Sandro Griesbach für, dass es jeder, der ohne das Heft nach Hause ge- 19 Löwenhertz Redaktion: Sascha Blach, Daniel Dreßler, Gert hen wollte, schwer hatte. Unseren WGT-Nachbericht 16 Mark Benecke Drexl, Peter Istuk, Bruno Kramm, Jennifer Laux, lest ihr ebenso in der euch nun vorliegenden Juli/ Sigmar Ost, Stephanie Riechelmann, Peter Sailer, Lea 9 Multimedia August-Ausgabe wie spannende Storys über Lacri- 14 No:Carrier Sommerhäuser, Laura Thon, Frank „Otti“ van Düren, mosa, Opeth, Letzte Instanz, Substaat oder Deine Kerstin Vielguth, Paul Winterfeld 26 Opeth Lakaien. -

Divx Na Cd Strona 1

Divx na cd 0000 0000 Original title/Tytul oryginalny 0000 Polish CD//Subt/Nap title/Tytul polski isy 10ThingsIHateAboutYou(1999) Zakochana zlosnica 1/pl 1492: Conquest of Paradise (AKA 1492: Odkrycie raju / 1492: Christophe1492:Wyprawa Colomb do / raju1492: La conquête du paradis / 1492: La conquista del paraíso) (1992) 2 Fast 2 Furious (2003) Za szybcy za wsciekli 1/pl 2046(2004) 2046 . 2/pl 21Grams (2003) 21 Gram 2/pl 25th Hour(2002) 25 godzina 2/pl 3000Miles toGraceland(2001) 3000 mil do Graceland 1/pl 50FirstDates(2004) 50 pierwszych randek 1/pl 54(1998) Klub 54 AboutSchmidt(2002) About Schmidt 2/pl Abrelosojos(AKA Open Your Eyes) (1997) Otworz oczy 1/pl Adaptation (2002) Adaptacja 2/pl Alfie(2004) Alfie 2/pl Ali(2001) Ali Alien3 (1992) Obcy 3 AlienResurrection (1997) 4 Obcy 4 – Przebudzenie Obcy 2 – Decydujace Aliens (1986) 2 starcie Alienvs. Predator(AKA Alienversus Predator/ AvP) (2004) Obcy Kontra Predator Amelia/ Fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulain, Le (AKA Amelie from AmeliaMontmartre / Amelie of Montmartre / Fabelhafte Welt der Amelie, Die / Fabulous Destiny of Amelie Poulain / Amelie) (2001) AmericanBeauty(1999) American Beauty AmericanPsycho(2000) American Psycho Anaconda(1997) Anakonda AngelHeart (1987) Harry Angel AngerManagement(2003) Dwoch gniewnych ludzi Animal Farm (1999) Folwark zwierzecy Animatrix, The(2003) Animatrix AntwoneFisher(2002) Antwone Fisher Apocalypse Now(AKA Apocalypse Now: Redux(2001)) (1979) DirApokalipsa cut Aragami(2003) Aragami Atame(AKA Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!) (1990) Zwiaz mnie Avalanche(AKA Nature -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin J

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2015 Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement Justin J. Grandinetti James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Rhetoric Commons, and the Visual Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grandinetti, Justin J., "Occupy the future: A rhetorical analysis of dystopian film and the Occupy movement" (2015). Masters Theses. 43. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/43 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Occupy the Future: A Rhetorical Analysis of Dystopian Film and the Occupy Movement Justin Grandinetti A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Writing, Rhetoric, and Technical Communication May 2015 Dedication Page This thesis is dedicated to the world’s revolutionaries and all the individuals working to make the planet a better place for future generations. ii Acknowledgements I’d like to thank a number of people for their assistance and support with this thesis project. First, a heartfelt thank you to my thesis chair, Dr. Jim Zimmerman, for always being there to make suggestions about my drafts, talk about ideas, and keep me on schedule. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Narratives, Cultural

DORISEA-Workshop Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and beyond. Narratives, cultural contexts, audiences October 3-6, 2012 University of Goettingen, Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology Convenor: Peter J. Braeunlein Abstracts Post-war Thai Cinema and the Supernatural: Style and Reception Context Mary Ainslie (Kuala Lumpur) Film studies of the last decade can be characterised by escalating scholarly interest in the diverse film forms of Far East Asian nations. In particular, such focus often turns to the ways in which the horror film can provide a culturally specific picture of a nation that offers insight into the internal conflicts and traumas faced by its citizens. Considering such research, the proposed paper will explore the lower-class ‘16mm era’ film form of 1950s and 60s Thailand, a series of mass-produced live-dubbed films that drew heavily upon the supernatural animist belief systems that organised Thai rural village life and deployed a film style appropriate to this context. Through textual analysis combined with anthropological and historical research, this essay will explore the ways in which films such as Mae-Nak-Prakanong (1959 dir. Rangsir Tasanapayak), Nguu-Phii (1966 dir. Rat Saet-Thaa-Phak-Dee), Phii-Saht-Sen-Haa (1969 dir. Pan-Kam) and Nang-Prai-Taa-Nii (1967 dir. Nakarin) deploy such discourses in relation to a dramatic wider context of social upheaval and the changes enacted upon rural lower-class viewers during this era, much of which was specifically connected to the post-war influx of American culture into Thailand. Finally it will indicate that the influence of this lower-class film style is still evident in the contemporary New Thai industry, illustrating that even in this global era of multiplex blockbusters such audiences and their beliefs and practices are still prominent and remain relevant within Thai society. -

The Monster-Child in Japanese Horror Film of the Lost Decade, Jessica

The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan “Our Fear Has Taken on a Life of its Own”: The Monster-Child in Japanese Horror Film of The Lost Decade, Jessica Balanzategui University of Melbourne, Australia 0168 The Asian Conference on Film and Documentary 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract The monstrous child of Japanese horror film has become perhaps the most transnationally recognisable and influential horror trope of the past decade following the release of “Ring” (Hideo Nakata, 1999), Japan’s most commercially successful horror film. Through an analysis of “Ring”, “The Grudge” (Takashi Shimizu, 2002), “Dark Water” (Nakata, 2002), and “One Missed Call” (Takashi Miike, 2003), I argue that the monstrous children central to J-horror film of the millenial transition function as anomalies within the symbolic framework of Japan’s national identity. These films were released in the aftermath of the collapse of Japan’s bubble economy in the early 1990s — a period known in Japan as ‘The Lost Decade’— and also at the liminal juncture represented by the turn of the millennium. At this cultural moment when the unity of national meaning seems to waver, the monstrous child embodies the threat of symbolic collapse. In alignment with Noël Carroll’s definition of the monster, these children are categorically interstitial and formless: Sadako, Toshio, Mitsuko and Mimiko invoke the wholesale destruction of the boundaries which separate victim/villain, past/present and corporeal/spectral. Through their disturbance to ontological categories, these children function as monstrous incarnations of the Lacanian gaze. As opposed to allowing the viewer a sense of illusory mastery, the J- horror monster-child figures a disruption to the spectator’s sense of power over the films’ diegetic worlds.