Dead Season1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Read a PDF Version of This Media Release, Click Here

MEDIA RELEASE 29 July 2020 The past isn’t done with us yet… Catherine Văn-Davies leads the ensemble cast of new Australian drama series Hungry Ghosts Four-night special event on SBS Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm • INTERVIEWS AVAILABLE • IMAGES AND SCREENERS: HERE • FIRST LOOK TRAILER: HERE Chilling, captivating and utterly compelling, Hungry Ghosts follows four families that find themselves haunted by ghosts from the past. Filmed and set in Melbourne during the month of the Hungry Ghost Festival, when the Vietnamese community venerate their dead, this four-part drama series event from Matchbox Pictures premieres over four consecutive nights, Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm on SBS. When a tomb in Vietnam is accidentally opened on the eve of the Hungry Ghost Festival, a vengeful spirit is unleashed, bringing the dead with him. As these spirits wreak havoc across the Vietnamese-Australian community in Melbourne, reclaiming lost loves and exacting revenge, young woman May Le (Văn-Davies) must rediscover her true heritage and accept her destiny to help bring balance to a community still traumatised by war. Hungry Ghosts reflects the extraordinary lived and spiritual stories of the Vietnamese community and explores the inherent trauma passed down from one generation to the next, and how notions of displacement impact human identity – long after the events themselves. With one of the most diverse casts featured in an Australian drama series, Hungry Ghosts comprises more than 30 Asian-Australian actors and 325 -

Lifelong Faith Formation Update for Parish Council 3/17/2021

Lifelong Faith Formation Update for Parish Council 3/17/2021 Last LFFC meeting 2/22/2021, next meeting 3/29/2021 LFFC will be updating Parish Council on the commission at the next Parish Council meeting, April 21, 2021 at 6:30 We continue to have Mary Dondlinger as Acting Chair of LFFC if Paul DeBruyne is unable to attend the LFFC meetings or fulfill his role as Chairperson. Faith Formation ‐Evaluating how to move forward next year (virtual, family, in‐person, etc.) Challenges when trying to do in‐person and virtual at the same time. ‐ First Communion: Retreat on March 20. First Communion Mass May 1/2 and May 15/16. ‐ MS/HS: Remaining retreat options are Archdiocesan Lenten Mission and the Easter Vigil Encounter. High School unit on Racial Justice has prompted conversations with families and the larger parish community. In general, systemic racism and social sin are areas of Catholic Social Teaching that most people are unfamiliar with. High School students plan to go to MacCanon Brown Homeless Sanctuary (MBHS) for a day of service and fellowship in April. ‐ National Catholic Youth Conference: QOA hopes to send a few youths to this conference in Indianapolis this November. Ticket fee is $585.00 and needs to be purchased by May 1. Participants will do fundraising and each participant from QOA has to pay $250.00 on their own. In the past, Queen of Apostles participated in the Positively Pewaukee Cars and Cookout Event and raised $1000 from brat sales in June 2019 for this trip. ‐ Adult Bible Study: Jesus: the Way, the Truth, and the Life, 10 session class continues through April 21/22. -

Holiday Sales Calendar China

Important Marketing Holidays of the China JANUARY 01 FEBRUARY 02 MARCH 03 01 New Year’s Day 05 Chinese Lunar New Year's Day 08 International Women's Day 24-25 Spring Festival 08 Lantern Festival 14 White Day 25 Chinese New Year 14 Valentine’s Day 15 Consumer Rights Day 28 Earth hour day APRIL 04 MAY 05 JUNE 06 01 April Fool’s Day 01 Labor Day 01 Children’s Day 04 Qingming Festival 10 Mother’s Day 25 Dragon Boat Festival 17 517 Festival 10-12 CES Asia 20 Online Valentine’s Day 18 618 Shopping Festival 21 Father’s Day JULY 07 AUGUST 08 SEPTEMBER 09 24 Tokyo Olympics will Begin 03 Men’s Day 10 Teacher’s Day 30 International Day of Friendship 08 Closing of the Tokyo Olympics 15 Harvest Celebration 25 Qixi / Chinese Valentine's Day Back to School Sales (Whole Month) OCTOBER 10 NOVEMBER 11 DECEMBER 12 01 Mid-autumn Festival 11 Single’s Day / Double Eleven 12 Double Twelve 01-07 National Day Golden Week 27 Black Friday 21 Winter Solstice 24 China Programmer Day 26 Thanksgiving Day 25 Christmas Day 25 Double Ninth Festival 30 Cyber Monday 31 Halloween https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/holiday-sales/ https://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-2-extensions https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/holiday-sales/ https://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-2-extensions Holidayhttps://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/holiday-sales/ Sales Tips Magento Extensions https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/trends-and-statistics/ https://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-developers-for-hire https://www.mconnectmedia.com/blog/category/trends-and-statistics/Latest eCommerce Trends Hirehttps://www.mconnectmedia.com/magento-developers-for-hire Magento Developer For more information visit - www.mconnectmedia.com https://www.mconnectmedia.com https://www.mconnectmedia.com. -

Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Narratives, Cultural

DORISEA-Workshop Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and beyond. Narratives, cultural contexts, audiences October 3-6, 2012 University of Goettingen, Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology Convenor: Peter J. Braeunlein Abstracts Post-war Thai Cinema and the Supernatural: Style and Reception Context Mary Ainslie (Kuala Lumpur) Film studies of the last decade can be characterised by escalating scholarly interest in the diverse film forms of Far East Asian nations. In particular, such focus often turns to the ways in which the horror film can provide a culturally specific picture of a nation that offers insight into the internal conflicts and traumas faced by its citizens. Considering such research, the proposed paper will explore the lower-class ‘16mm era’ film form of 1950s and 60s Thailand, a series of mass-produced live-dubbed films that drew heavily upon the supernatural animist belief systems that organised Thai rural village life and deployed a film style appropriate to this context. Through textual analysis combined with anthropological and historical research, this essay will explore the ways in which films such as Mae-Nak-Prakanong (1959 dir. Rangsir Tasanapayak), Nguu-Phii (1966 dir. Rat Saet-Thaa-Phak-Dee), Phii-Saht-Sen-Haa (1969 dir. Pan-Kam) and Nang-Prai-Taa-Nii (1967 dir. Nakarin) deploy such discourses in relation to a dramatic wider context of social upheaval and the changes enacted upon rural lower-class viewers during this era, much of which was specifically connected to the post-war influx of American culture into Thailand. Finally it will indicate that the influence of this lower-class film style is still evident in the contemporary New Thai industry, illustrating that even in this global era of multiplex blockbusters such audiences and their beliefs and practices are still prominent and remain relevant within Thai society. -

Hauntology Beyond the Cinema: the Technological Uncanny 66 Closings 78 5

Information manycinemas 03: dread, ghost, specter and possession ISSN 2192-9181 Impressum manycinemas editor(s): Michael Christopher, Helen Christopher contact: Matt. Kreuz Str. 10, 56626 Andernach [email protected] on web: www.manycinemas.org Copyright Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. The authors are free to re - publish their text elsewhere, but they should mention manycinemas as the first me- dia which has published their article. According to §51 Nr. 2 UrhG, (BGH, Urt. v. 20.12.2007, Aktz.: I ZR 42/05 – TV Total) German law, the quotation of pictures in academic works are allowed if text and screenshot are in connectivity and remain unchanged. Open Access manycinemas provides open access to its content on the principle that mak - ing research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge. Front: Screenshot The cabinet of Caligari Contents Editorial 4 Helen Staufer and Michael Christopher Magical thrilling spooky moments in cinema. An Introduction 6 Brenda S. Gardenour Left Behind. Child Ghosts, The Dreaded Past, and Reconciliation in Rinne, Dek Hor, and El Orfanato 10 Cen Cheng No Dread for Disasters. Aftershock and the Plasticity of Chinese Life 26 Swantje Buddensiek When the Shit Starts Flying: Literary ghosts in Michael Raeburn's film Triomf 40 Carmela Garritano Blood Money, Big Men and Zombies: Understanding Africa’s Occult Narratives in the Context of Neoliberal Capitalism 50 Carrie Clanton Hauntology Beyond the Cinema: The Technological Uncanny 66 Closings 78 5 Editorial Sorry Sorry Sorry! We apologize for the late publishing of our third issue. -

Religious Holidays

10 22 Religious Waqf al Arafa/Hajj Day | Ganesh Chaturthi | Hindu Muslim Festival honoring the god of (until 8/11) prosperity, prudence, and success Holidays Observance during Hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, when pilgrims pray for forgiveness and 29 mercy Beheading of St. John the Baptist | Christian Provided by Krishna Janmashtani | Hindu Remembrance of the death of Commemoration of the birth of John the Baptist The President's Krishna Committee on September 15 Religious, Assumption of the Blessed 1 Virgin Mary | Catholic Christian Religious year begins | Spiritual and Commemorating the assumption of Orthodox Christian Mary, mother of Jesus, into Start of the religious calendar year Nonreligious heaven Diversity Dormition of the Virgin Mary | 2 Orthodox Christian Obon/Ulambana | Buddhist, Observance of the death, burial, Shinto and transfer to heaven of the Also known as Ancestor Day, a Virgin Mary time to relieve the suffering of ghosts by making offerings to deceased ancestors 2020 16 Paryushana Parva | Jain Chinese Ghost Festival | August Festival signifying human Taoist, Buddhist emergence into a new world of Celebration in which the deceased spiritual and moral refinement, and are believed to visit the living 1 a celebration of the natural Lammas | Wiccan/Pagan qualities of the soul Celebration of the early harvest 8 Nativity of the Blessed Virgin 17 Fast in Honor of Holy Mother Mary | Orthodox Christian Marcus Garvey’s Birthday | of Jesus | Orthodox Christian Celebration of the birth of Mary, Beginning of the 14-day period -

Inheritance Path of Traditional Festival Culture from the Perspective of Ghost Festival in Luju Town

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 7, Ver. IV (July. 2014), PP 43-47 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Inheritance Path of Traditional Festival Culture from the Perspective of Ghost Festival in Luju Town Jiayi Lu, Jianghua Luo 1,2Key Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences at University, Center for Studies Education and Psychology of Ethnic Minorities in Southwestern China, Southwest University, Beibei , Chongqing 400715 Abstract: By participating in a series of activities of Ghost Festival on July 15th, teenagers naturally accept the ethical education of filial piety and benevolence. However, under the background of urbanization of villages, teenagers are away from their local families, and family controlling power and influence have been weakened. All these problems become prominent increasingly. As a result, the cultural connotations of Ghost Festival have been misinterpreted, and its survival and inheritance are facing a crisis. Therefore, we must grasp the essence in the inheritance of traditional cultures and make families and schools play their roles on the basis of combination of modern lives. Keywords: Ghost Festival, local villages, inheritance of culture, teenagers Fund Project: Comparative Study of the Status Quo of Educational Development of Cross-border Ethnic Groups in Southwestern China — major project of humanities and social science key research base which belongs to the Ministry of Education. (Project Number: 11JJD880028) About the Author: Lu Jiayi, student of Southwestern Ethnic Education and Psychology Research Center of Southwest University, Luo Jianghua, associate professor of Southwestern Ethnic Education and Psychology Research Center of Southwest University, PhD,Chongqing 400715. -

Student Worksheet a A) 烧香 Shāoxiāng B) 做灯笼 Zuò Dēnglóng

Student Worksheet A Look at the images below- what can you see? What do you think connects them all? What is happening? 1 2 3 4 Match the vocabulary with the correct photograph (you will need a dictionary or an online dictionary): a) 烧香 shāoxiāng b) 做灯笼 zuò dēnglóng c) 烧纸钱 shāo qián zhǐ d) 给食物 gěi shíwù Now read this website to find the answers. Tell your partner what you have found out, and teach them the new Chinese you have learned. Write four sentences in Chinese to tell your partner about Hungry Ghost Festival, using the vocabulary above, for example: 1. 在鬼节你烧纸钱 2. 3. 4. Student Worksheet B Look at the images below- what is happening? What do you think connects them all? 1 2 3 4 Match the vocabulary with the correct photograph (you will need a dictionary or an online dictionary): a) 吹口哨 chuīkǒushào b) 回头 huítóu c) 穿高跟鞋 chuān gāogēnxié d) 游泳 yóuyǒng Now go to this website and find out the answer… Tell your partner what you have found out, and teach them the new Chinese you have learned. Write four sentences in Chinese to tell your partner about Hungry Ghost Festival, using the vocabulary above, for example: 1. 在鬼节你不能吹口哨 2. 3. 4. More Vocabulary (Hungry) Ghost Month 鬼月 Guǐ yuè Hungry Ghost Festival: 盂兰盆 Yúlánpén, 中元节 Zhōngyuán Jié, 鬼节 Guǐ Jié Buddhism 佛教 Fójiào Taoism 道教 Dàojiào With your partner, read about the Hungry Ghost Festival: Hungry Ghost Festival The Hungry Ghost Festival is one of several important festival days of Ghost Month (鬼月 Guǐ yuè) — the seventh month of the Chinese lunar calendar. -

China Treasure Hunt! Check Your Answers Below

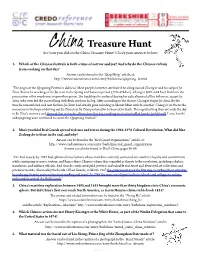

Treasure Hunt See how you did on the China Treasure Hunt! Check your answers below: 1. Which of the Chinese festivals is both a time of sorrow and joy? And why do the Chinese refrain from cooking on that day? Answer can be found in the “Qing Ming” article, at: http://www.credoreference.com/entry/berkchina/qingming_festival “The origin of the Qingming Festival is dubious. Most people, however, attribute it to a king named Chong’er and his subject Jie Zitui. Before he was king of the Jin state in the Spring and Autumn period (770–476 bce), Chong’er (697–628 bce) fled from the persecution of his murderous stepmother queen. The hardships he endured during his exile alienated all his followers, except Jie Zitui, who even fed the starved king with flesh cut from his leg. After ascending to the throne, Chong’er forgot Jie Zitui. By the time he remembered and sent for him, Jie Zitui had already gone in hiding to Mount Mian with his mother. Chong’er set fire to the mountain in the hope of driving out Jie Zitui; but Jie Zitui preferred to be burned to death. The regretful king then set aside the day in Jie Zitui’s memory and decreed that no fire be allowed on that day, resulting in a festival called hanshi (cold food). Later, hanshi and qingming were combined to create the Qingming Festival.” 2. Mao’s youthful Red Guards spread violence and terror during the 1966-1976 Cultural Revolution. What did Mao Zedong do to them in the end, and why? Answer can be found in the “Red Guard Organizations” article, at: http://www.credoreference.com/entry/berkchina/red_guard_organizations ChinaAnswer can also be found in This Is China, pages 98-99. -

Ancient China Review

Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? Ancient China Question 1 This river in China is the second longest in the world? A Huang He B He Huang C Hang He D Hang Ha A Huang He B He Huang C Hang He D Hang Ha Question 2 What does Huang He mean? A Golden River B Yellow Flower C Yellow River D Golden Ribbon A Golden River B Yellow Flower C Yellow River D Golden Ribbon Question 3 The name of the 2nd major river in China? A Yanger B Yangzer C Yangly D Yangtze A Yanger B Yangzer C Yangly D Yangtze Question 4 What did the people build about fourteen hundred years ago to connect the two rivers? A Canal B Trench C Highway D Candy land path A Canal B Trench C Highway D Candy land path Question 5 How did they continue to honor their ancestors? A Continuing to set a place for them at the table. B Continuing to keep their clothes hung up in the closet. C Continuing to talk to them, bring small gifts and carve their names on little wooden blocks. D Continuing to talk to them and keep their things in their closet. A Continuing to set a place for them at the table. B Continuing to keep their clothes hung up in the closet. C Continuing to talk to them, bring small gifts and carve their names on little wooden blocks. D Continuing to talk to them and keep their things in their closet. Question 6 These festivals are two ancient celebrations held in honor of all ancestors? A Qingmen Festival and Hungry Crane Festival B Qingming Festival and Hungry Ghost Festival C Qingmeng Festival and Hungry Crow Festival D Qingming Festival and Hungry Gnat Festival A Qingmen Festival -

Holidays Top Famous Numbers Chinese – – – – – Day3 Day4 Day5 Day1 Day2 Week1 Week2 Week3 Week4 Agenda Holidays in China Useful Words for Mandarin Entry Day 3 Holidays

知 行 Gee Sing Mandarin 汉 语 Agenda Week1 Phonetic Transcription Week2 Tones and rules Week3 Strokes and writing Week4 Useful words Day1 – Numbers Day2 – Chinese Zodiac Day3 – Holidays in China Day4 – Top cities Day5 – Famous attractions Holidays in China Useful words for Mandarin Entry Day 3 Holidays jié rì 节日 The traditional Chinese holidays are an essential part of harvests or prayer offerings. The most important Chinese holiday is the Chinese New Year (Spring Festival), which is also celebrated in Taiwan and overseas ethnic Chinese communities. All traditional holidays are scheduled according to the Chinese calendar. Day 3 Holidays chú xī 除夕 dà nián sān shí 大年三十 Chinese New Year Eve, Last day of lunar year Family get together and celebrate the end of the year. Usually, we stay up to midnight to embrace the lunar new year. The elderly will give lucky money(红hóng包bāo) to the young generations. Day 3 Holidays chūn jié 春节 dà nián chū yī 大年初一 Chinese New Year (Spring Festival), The first day of January (lunar calendar) Set off fireworks after midnight; visit family members; Many ceremonies and celebration activities. Day 3 Holidays yuán xiāo jié 元宵节 zhēng yuè shí wǔ 正月十五 Lantern Festival , Fifteenth day of January (lunar calendar) Lantern parade and lion dance celebrating the first full moon. Eating 汤圆(tāngyuán). This day is also the last day of new year celebration. Day 3 Holidays qīng míng jié 清明节 sì yuè wǔ rì 四月五日 Qingming Festival (Tomb Sweeping Festival, Tomb Sweeping Day, Clear and Bright Festival) Visit, clean, and make offerings at ancestral gravesites, spring outing Day 3 Holidays duān wǔ jié 端午节 wǔ yuè chū wǔ 五月初五 Duanwu Festival (Dragon Boat Festival), Fifth day of May (lunar calendar) Dragon boat race, eat sticky rice wrapped in lotus leaves 粽子(zòngzǐ). -

Download the Schedule for the Celebrations

religions Article Live Streaming and Digital Stages for the Hungry Ghosts and Deities Alvin Eng Hui Lim Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore, Block AS5, 7 Arts Link, Singapore 117570, Singapore; [email protected] Received: 25 May 2020; Accepted: 10 July 2020; Published: 17 July 2020 Abstract: Many Chinese temples in Singapore provide live streaming of getai (English: a stage for songs) during the Hungry Ghost Month as well as deities’ birthday celebrations and spirit possessions—a recent phenomenon. For instance, Sheng Hong Temple launched its own app in 2018, as part of a digital turn that culminated in a series of live streaming events during the temple’s 100-year anniversary celebrations. Deities’ visits to the temple from mainland China and Taiwan were also live-streamed, a feature that was already a part of the Taichung Mazu Festival in Taiwan. Initially streamed on RINGS.TV, an app available on Android and Apple iOS, live videos of getai performances can now be found on the more sustainable platform of Facebook Live. These videos are hosted on Facebook Pages, such as “Singapore Getai Supporter” (which is listed as a “secret” group), “Singapore Getai Fans Page”, “Lixin Fan Page”, and “LEX-S Watch Live Channel”. These pages are mainly initiated and supported by LEX(S) Entertainment Productions, one of the largest entertainment companies running and organising getai performances in Singapore. This paper critically examines this digital turn and the use of digital technology, where both deities and spirits are made available to digital transmissions, performing to the digital camera in ways that alter the performative aspects of religious festivals and processions.