Cinema and New Technologies: the Development of Digital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Producer's Handbook

DEVELOPMENT AND OTHER CHALLENGES A PRODUCER’S HANDBOOK by Kathy Avrich-Johnson Edited by Daphne Park Rehdner Summer 2002 Introduction and Disclaimer This handbook addresses business issues and considerations related to certain aspects of the production process, namely development and the acquisition of rights, producer relationships and low budget production. There is no neat title that encompasses these topics but what ties them together is that they are all areas that present particular challenges to emerging producers. In the course of researching this book, the issues that came up repeatedly are those that arise at the earlier stages of the production process or at the earlier stages of the producer’s career. If not properly addressed these will be certain to bite you in the end. There is more discussion of various considerations than in Canadian Production Finance: A Producer’s Handbook due to the nature of the topics. I have sought not to replicate any of the material covered in that book. What I have sought to provide is practical guidance through some tricky territory. There are often as many different agreements and approaches to many of the topics discussed as there are producers and no two productions are the same. The content of this handbook is designed for informational purposes only. It is by no means a comprehensive statement of available options, information, resources or alternatives related to Canadian development and production. The content does not purport to provide legal or accounting advice and must not be construed as doing so. The information contained in this handbook is not intended to substitute for informed, specific professional advice. -

Co-Produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the Vision

Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia the vision. the voice. From LA to London and Martinique to Mali. We bring you the world ofBlack film. Ifyou're concerned about Black images in commercial film and tele vision, you already know that Hollywood does not reflect the multi- cultural nature 'ofcontemporary society. You know thatwhen Blacks are not absent they are confined to predictable, one-dimensional roles. You may argue that movies and television shape our reality or that they simply reflect that reality. In any case, no one can deny the need to take a closer look atwhat is COIning out of this powerful medium. Black Film Review is the forum you've been looking for. Four times a year, we bringyou film criticiSIn froIn a Black perspective. We look behind the surface and challenge ordinary assurnptiorls about the Black image. We feature actors all.d actresses th t go agaul.st the graill., all.d we fill you Ul. Oll. the rich history ofBlacks Ul. Arnericall. filrnrnakul.g - a history thatgoes back to 19101 And, Black Film Review is the only magazine that bringsyou news, reviews and in-deptll interviews frOtn tlle tnost vibrant tnovetnent in contelllporary film. You know about Spike Lee butwIlat about EuzIlan Palcy or lsaacJulien? Souletnayne Cisse or CIl.arles Burnette? Tllrougll out tIle African cliaspora, Black fi1rnInakers are giving us alternatives to tlle static itnages tIlat are proeluceel in Hollywood anel giving birtll to a wIlole new cinetna...be tIlere! Interview:- ----------- --- - - - - - - 4 VDL.G NO.2 by Pat Aufderheide Malian filmmaker Cheikh Oumar Sissoko discusses his latest film, Finzan, aself conscious experiment in storytelling 2 2 E e Street, NW as ing on, DC 20006 MO· BETTER BLUES 2 2 466-2753 The Music 6 o by Eugene Holley, Jr. -

BULLETIN for FILM and VIDEO INFORMATION Vol. 1,No.1

EXHIBITION AND PROGRAMMING in New York : BULLETIN FOR FILM AND VIDEO INFORMATION Independent Film Showcases Film Archives, 80 Wooster st. N.Y.,N.Y.10012 Vol. 1,No .1,January 1974 Anthology (212)758-6327 Collective for the Living Cinema, 108 E 64St . N.Y.,NY.10021 Forum, 256 W 88 St . N.Y .,N .Y.10024 (212)362-0503 Editor : Hollis Melton ; Publisher : Anthology Film Archives ; Film Millennium, 46 Great Jones St. N.Y .,N.Y.10003, (212) 228-9998 Address: 80 Wooster st., New York, N .Y. 10012; Yearly subscription : $2 Museum of Modern Art, 11 W 53 St . N.Y.,N.Y.10019 (212) 956-7078 U-P Screen, 814 Broadway at E 11th St . N.Y. N.Y. 10003 Whitney Museum, 945 Madison Ave . at 75St . N.Y.,N.Y.10021 (212) 861-5322 needs of independent The purpose of this bulletin is to serve the information San :Francisco : their users. The bulletin is organized around five film and video-makers and Canyon Cinematheque,San Francisco Art Institute, 800 Chestnut St., film and video-making ; distribution ; exhibition aspects of film and video: San Francisco, Ca . (415) 332-1514 ; study; and preservation . There is very little in this iddue and programming Film Archive, University Art Museum, Berkeley, Ca. 94720 due to a lack of response from video-makers . Your suggetions and Pacific on video (415) 642-1412 comments will be welcomed . San Francisco Museum of Art, Van Ness & McAllister Streets, San Francisco Ca. (415) 863-8800 DISTRIBUTION that Include Screening Work by A brief note on non-exclusive distribution Regional Centers with Film Programs Independent Film-makers. -

A Filmmakers' Guide to Distribution and Exhibition

A Filmmakers’ Guide to Distribution and Exhibition A Filmmakers’ Guide to Distribution and Exhibition Written by Jane Giles ABOUT THIS GUIDE 2 Jane Giles is a film programmer and writer INTRODUCTION 3 Edited by Pippa Eldridge and Julia Voss SALES AGENTS 10 Exhibition Development Unit, bfi FESTIVALS 13 THEATRIC RELEASING: SHORTS 18 We would like to thank the following people for their THEATRIC RELEASING: FEATURES 27 contribution to this guide: PLANNING A CINEMA RELEASE 32 NON-THEATRIC RELEASING 40 Newton Aduaka, Karen Alexander/bfi, Clare Binns/Zoo VIDEO Cinemas, Marc Boothe/Nubian Tales, Paul Brett/bfi, 42 Stephen Brown/Steam, Pamela Casey/Atom Films, Chris TELEVISION 44 Chandler/Film Council, Ben Cook/Lux Distribution, INTERNET 47 Emma Davie, Douglas Davis/Atom Films, CASE STUDIES 52 Jim Dempster/bfi, Catharine Des Forges/bfi, Alnoor GLOSSARY 60 Dewshi, Simon Duffy/bfi, Gavin Emerson, Alexandra FESTIVAL & EVENTS CALENDAR 62 Finlay/Channel 4, John Flahive/bfi, Nicki Foster/ CONTACTS 64 McDonald & Rutter, Satwant Gill/British Council, INDEX 76 Gwydion Griffiths/S4C, Liz Harkman/Film Council, Tony Jones/City Screen, Tinge Krishnan/Disruptive Element Films, Luned Moredis/Sgrîn, Méabh O’Donovan/Short CONTENTS Circuit, Kate Ogborn, Nicola Pierson/Edinburgh BOXED INFORMATION: HOW TO APPROACH THE INDUSTRY 4 International Film Festival, Lisa Marie Russo, Erich BEST ADVICE FROM INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS 5 Sargeant/bfi, Cary Sawney/bfi, Rita Smith, Heather MATERIAL REQUIREMENTS 5 Stewart/bfi, John Stewart/Oil Factory, Gary DEALS & CONTRACTS 8 Thomas/Arts Council of England, Peter Todd/bfi, Zoë SHORT FILM BUREAU 11 Walton, Laurel Warbrick-Keay/bfi, Sheila Whitaker/ LONDON & EDINBURGH 16 article27, Christine Whitehouse/bfi BLACK & ASIAN FILMS 17 SHORT CIRCUIT 19 Z00 CINEMAS 20 The editors have made every endeavour to ensure the BRITISH BOARD OF FILM CLASSIFICATION 21 information in this guide is correct at the time of GOOD FILMS GOOD PROGRAMMING 22 going to press. -

Entertainment

ENTERTAINMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2011 PROFILE Village Roadshow was founded by Roc Kirby and first commenced business in 1954 in Melbourne, Australia and has been listed on the Australian Securities Exchange since 1988. Still based in Melbourne, Village Roadshow Limited (‘VRL’) is a leading international entertainment company with core businesses in Theme Parks, Cinema Exhibition, Film Distribution and Film Production and Music. All of these businesses are well recognised retail brands and strong cash flow generators - together they create a diversified portfolio of entertainment assets. Theme Parks Village Roadshow has been involved in theme and Sea World Helicopters; parks since 1989 and is Australia’s largest • Australian Outback Spectacular; and theme park owner and operator. • Paradise Country and Village Roadshow On Queensland’s Gold Coast VRL has: Studios. • Warner Bros. Movie World, the popular VRL is moving forward with plans to build movie themed park; Australia’s newest water theme park, • Sea World, Australia’s premier marine Wet‘n’Wild Sydney, with site development theme park; to begin in the 2012 calendar year. • Wet‘n’Wild Water World, one of the world’s VRL’s overseas theme parks are: largest and most successful water parks; • Wet’n’Wild Hawaii, USA; and • Sea World Resort and Water Park, • Wet’n’Wild Phoenix, Arizona USA. Cinema Exhibition Showing movies has a long tradition with at 8 sites in the United States and 12 screens Village Roadshow, having started in 1954 in the UK. VRL continues to lead the world with the first of its drive–in cinemas. Today with industry trends including stadium Village Cinemas jointly owns and operates seating, digital projection, 3D blockbuster 506 screens across 50 sites in Australia, 73 movies and the growth category of premium screens at 9 sites in Singapore, 59 screens cinemas including Gold Class. -

African Studies Association 59Th Annual Meeting

AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION 59TH ANNUAL MEETING IMAGINING AFRICA AT THE CENTER: BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP, POLICY, AND REPRESENTATION IN AFRICAN STUDIES December 1 - 3, 2016 Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C. PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Benjamin N. Lawrance, Rochester Institute of Technology William G. Moseley, Macalester College LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Eve Ferguson, Library of Congress Alem Hailu, Howard University Carl LeVan, American University 1 ASA OFFICERS President: Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University Vice President: Anne Pitcher, University of Michigan Past President: Toyin Falola, University of Texas-Austin Treasurer: Kathleen Sheldon, University of California, Los Angeles BOARD OF DIRECTORS Aderonke Adesola Adesanya, James Madison University Ousseina Alidou, Rutgers University Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Columbia University Brenda Chalfin, University of Florida Mary Jane Deeb, Library of Congress Peter Lewis, Johns Hopkins University Peter Little, Emory University Timothy Longman, Boston University Jennifer Yanco, Boston University ASA SECRETARIAT Suzanne Baazet, Executive Director Kathryn Salucka, Program Manager Renée DeLancey, Program Manager Mark Fiala, Financial Manager Sonja Madison, Executive Assistant EDITORS OF ASA PUBLICATIONS African Studies Review: Elliot Fratkin, Smith College Sean Redding, Amherst College John Lemly, Mount Holyoke College Richard Waller, Bucknell University Kenneth Harrow, Michigan State University Cajetan Iheka, University of Alabama History in Africa: Jan Jansen, Institute of Cultural -

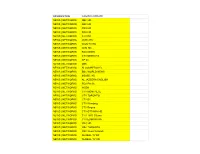

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Catalogue2007.Pdf

Sommaire / Contents Comité National d'Organisation / The National Organising Committee 6 Mot du Ministre de la Culture des Arts et du Tourisme / Speech of the Minister of Culture, Arts and Tourism 7 Mot du président d'honneur / Speech of honorary chairperson 8 Mot du Président du Comité d'Organisation / Speech of the President of the Organising Committee 9 Mot du Président du Conseil d’Administration / / Speech of the President of Chaireperson of the Board of Adminsitration 11 Mot du Maire de la ville de Ouagadougou / Speech of the Mayor of the City of Ouagadougou 12 Mot du Délégué Général du Fespaco / Speech of the General Delegate of Fespaco 13 Regard sur Manu Dibango, président d'honneur du 20è festival / Focus on Manu Dibango, Chair of Honor 15 Film d'Ouverture / Opening film 19 Jury longs métrages / Feature film jury 22 Liste compétition longs métrages / Competing feature films 24 Compétition longs métrages / Feature film competition 25 Jury courts métrages et films documentaires / Short and documentary film jury 37 Liste compétition courts métrages / Competing short films 38 Compétition courts métrages / Short films competition 39 Liste compétition films documentaires / Competing documentary films 49 Compétition films documentaires / Documentary films competition 50 3 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 59 Panorama des cinémas d'Afrique longs métrages / Panorama of cinema from Africa - Feature films 60 Liste panorama des cinémas d'Afrique courts métrages / Panorama -

The Reimagined Paradise: African Immigrants in the United States, Nollywood Film, and the Digital Remediation of 'Home'

THE REIMAGINED PARADISE: AFRICAN IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES, NOLLYWOOD FILM, AND THE DIGITAL REMEDIATION OF 'HOME' Tori O. Arthur A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2016 Committee: Radhika Gajjala, Advisor Patricia Sharp Graduate Faculty Representative Vibha Bhalla Lara Lengel © 2016 Tori O. Arthur All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Radhika Gajjala, Advisor This dissertation analyzes how African immigrants from nations south of the Sahara become affective citizens of a universal Africa through the consumption of Nigerian cinema, known as Nollywood, in digital spaces. Employing a phenomenological approach to examine lived experience, this study explores: 1) how American media aids African pre-migrants in constructing the United States as a paradise rooted in the American Dream; 2) immigrants’ responses when the ‘imagined paradise’ does not match their American realities; 3) the ways Nigerian films articulate a distinctly African cultural experience that enables immigrants from various nations to identify with the stories reflected on screen; and, 4) how viewing Nollywood films in social media platforms creates a digital sub-diaspora that enables a reconnection with African culture when life in the United States causes intellectual and emotional dissonance. Using voices of members from the African immigrant communities currently living in the United States and analysis of their online media consumption, this study ultimately argues that the Nigerian film industry, a transnational cinema with consumers across the African diaspora, continuously creates a fantastical affective world that offers immigrants tools to connect with their African cultural values. -

Channels List

INFORMATION COVID19 UPDATE NEWS | NETWORKS NBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBS HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS WGN TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CNN HD NEWS | NETWORKS FOX NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS CTV NEWS HD NEWS | NETWORKS CP 24 NEWS | NETWORKS BNN NEWS | NETWORKS BLOOMBERG HD NEWS | NETWORKS BBC WORLD NEWS NEWS | NETWORKS MSNBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS AL JAZEERA ENGLISH NEWS | NETWORKS FOX Pacific NEWS | NETWORKS WSBK NEWS | NETWORKS CTV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CTV BC NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Winnipeg NEWS | NETWORKS CTV Regina NEWS | NETWORKS CTV OTTAWA HD NEWS | NETWORKS CTV TWO Ottawa NEWS | NETWORKS CTV EDMONTON NEWS | NETWORKS CBC HD NEWS | NETWORKS CBC TORONTO NEWS | NETWORKS CBC News Network NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV BC NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV CALGARY NEWS | NETWORKS GLOBAL TV MONTREAL NEWS | NETWORKS CITY TV HD NEWS | NETWORKS CITY VANCOUVER NEWS | NETWORKS WBTS NEWS | NETWORKS WFXT NEWS | NETWORKS WEATHER CHANNEL USA NEWS | NETWORKS MY 9 HD NEWS | NETWORKS WNET HD NEWS | NETWORKS WLIW HD NEWS | NETWORKS CHCH NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 1 NEWS | NETWORKS OMNI 2 NEWS | NETWORKS THE WEATHER NETWORK NEWS | NETWORKS FOX BUSINESS NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 Miami NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 10 San Diego NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 12 San Antonio NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 13 HOUSTON NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 2 ATLANTA NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 4 SEATTLE NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 5 CLEVELAND NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 9 ORANDO HD NEWS | NETWORKS ABC 6 INDIANAPOLIS HD NEWS | NETWORKS -

Festivalteilnahmen Deutscher Filme Auf Internationalen Filmfestivals 2018

FESTIVALTEILNAHMEN DEUTSCHER FILME AUF INTERNATIONALEN FILMFESTIVALS 2018 KOPRODUKTIONSLÄNDER DATUM BEGINN FESTIVAL DATUM ENDE FESTIVALS SEKTION FILMTITEL REGIE (bei rein deutschen Produktionen FESTIVAL kein Eintrag) Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Special Presentation AUS DEM NICHTS Fatih Akin DE/FR New Voices/New Visions Competition for Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 DREI ZINNEN Jan Zabeil DE/IT Directorial Debut Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film A FANTASTIC WOMAN Sebastián Lelio CL/US/DE/ES Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film FÉLICITÉ Alain Gomis FR/SN/BE/DE/LB Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film FOXTROT Samuel Maoz DE/IL/FR/CH Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film LOVELESS Andrey Zvyagintsev RU/BE/DE/FR Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film MEN DON'T CRY Alen Drljevic BH/SL/HR/DE Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film THE WOUND John Trengove ZA/DE Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film TOM OF FINLAND Dome Karukoski FI/SE/DK/DE Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. Januar 2018 15. Januar 2018 Awards Buzz: Best Foreign Language Film UNDER THE TREE Hafsteinn Gunnar Sigurdsson IS/PL/DK/DE Palm Springs International Film Festival 2. -

2016 Ghana Social Media Rankings Report

2017 The 2016 Annual Ghana Social Media Report A RANKINGS REPORT ON THE MOST INFLUENTIAL BRANDS AND PERSONALITIES ON SOCIAL MEDIA IN GHANA A RESEARCH PROJECT BY CLIQAFRICA LIMITED AND AVANCE MEDIA WWW.CLIQAFRICA.COM/GSMR GSMR 2016 CLIQAFRICA |AVANCE MEDIA FOREWORD With the growing dynamism in the global digital space, digital trends in 2016 show an increased sophistication of our social world and increased connectivity of human online activities specifically on social media. The year 2016 also witnessed several online controversies and events both globally and locally such as the #Brexit trend to various elections conversations, notable among them were the 2016 US Election, the 2016 Ghana elections and the Gambian Elections which occurrences happened almost concurrently and sparked an unending social revolution and brand advocacy. Social Media shaped how these controversies spurred generally with more online or digital platforms as well as brands focusing on media sharing on social media communities for traffic generation rather than employing any other network to reach out to audience. We also saw a global changing trend in content delivery and consumption as well as changing behavioral patterns of users and audience on these social networks. Social media measurement and monitoring thus became one of the most important features for most brands, organizations and businesses in their urge to guide their implementation of social campaigns and shape their online brand voice. In Ghana, various forecast and predictions were made notably by brands, personalities, organizations and civil society groups which spiraled these controversies to the extent of a proposed censorship of social media during the 2016 general elections as seen in other countries during periods of escalated controversies.