Total Transport: Feasibility Report & Pilot Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13/2136C Rectory Farm, Knutsford Road, Church Lawton, Stoke-On

Application No: 13/2136C Location: Rectory Farm, Knutsford Road, Church Lawton, Stoke-on-Trent, ST7 3EQ Proposal: Outline application for demolition of house, garage, barns and outbuildings, removal of hardstanding and construction of housing development Applicant: Northwest Heritage Expiry Date: 27-Aug-2013 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATION Approve with conditions MAIN ISSUES • Principle of Development • Sustainability • Character and Appearance • Landscape Impact • Ecology • Highway Safety and Traffic Generation. • Affordable Housing • Drainage and Flooding • Open Space • Residential Amenity • Other Considerations REFERRAL The application has been referred to the Southern Planning Committee because the site area is just over 0.5 hectares in size and is therefore a small scale major development. 1. SITE DESCRIPTION This application relates to the former Rectory Farm situated to the northwest of Church Lawton and to the east of the Town of Alsager. The site lies wholly within the Infill Boundary Line for Lawton Gate, which is a small settlement washed over by Green Belt. The site accommodates the main rectory farm dormer bungalow, a detached dormer ancillary outbuilding and some detached barns / stables towards. To the north and the east, the site is bound by field and paddocks. Beyond the northern boundary of the site, the levels drop away significantly where the curtilage of Rectory Farm ceases. The land slopes downwards towards a brook beyond which there is the Trent and Mersey Canal which occupies an elevated position relative to the northern end of the site. The site can be viewed from the adjacent canal towpath. There are residential properties further to the east and residential properties bounding the southern boundary of the site which form part of the Lawton Gate settlement. -

Borough Profile 2020 Warrington

Borough profile 2020 Warrington 6 4 3 117 122 118 115 9 5 19 120 7 Warrington Wards 2 13 1 1. Appleton 12. Latchford West 110 11 12 2. Bewsey & Whitecross 13. Lymm North & Thelwall 1 14 3. Birchwood 14. Lymm South 4. Burtonwood & Winwick 15. Orford 116 21 5. Chapelford & Old Hall 16. Penketh & Cuerdley 8 6. Culcheth, Glazebury & Croft 17. Poplars & Hulme 7. Fairfield & Howley 18. Poulton North 8. Grappenhall 19. Poulton South 1 9. Great Sankey North & Whittle Hall 20. Rixton & Woolston 10. Great Sankey South 21. Stockton Heath 11. Latchford East 22. Westbrook Produced by Business Intelligence Service Back to top Contents 1. Population of Warrington 2. Deprivation 3. Education - Free School Meals (FSM) 4. Education - Special Educational Needs (SEN) 5. Education - Black Minority Ethnic (BME) 6. Education - English as an Additional Language (EAL) 7. Education - (Early Years aged 4/5) - Early Years Foundation Stage: Good Level of Development (GLD) 8. Education - (End of primary school aged 10/11) – Key Stage 2: Reading, Writing and Maths 9. Education (end of secondary school aged 15/16) – Key Stage 4: Progress 8 10. Education (end of secondary school aged 15/16) – Key Stage 4: Attainment 8 11. Health - Life expectancy 12. Health - Low Birthweight 13. Health - Smoking at time of delivery 14. Health - Overweight and obese reception children 15. Health - Overweight and obese Year 6 children 16. Children’s Social Care – Children in Need 17. Adult Social Care – Request for Support from new clients 18. Adult Social Care – Sequel to the Requests for Support 19. Adult Social Care – Number of clients accessing Long Term Support 20. -

Cheshire and Warrington

Children and Young People Health and Wellbeing Profile: Cheshire and Warrington Public Health Institute, Faculty of Education, Health and Community, Liverpool John Moores University, Henry Cotton Campus, 15-21 Webster Street, Liverpool, L3 2ET | 0151 231 4452 | [email protected] | www.cph.org.uk | ISBN: 978-1-910725-80-1 (web) Contents Acknowledgements 1 Introduction 2 Child to young person life course infographic 3 1 Children and young people in Cheshire and Warrington 4 2 Pre-birth and early years 5 3 Primary school 6 4 Secondary school to young adults 7 Interpretation guide 9 Data sources 9 Acknowledgements The Public Health Institute, Liverpool John Moores University was commissioned to undertake this work by the Cheshire and Merseyside Directors of Public Health through the Cheshire and Merseyside Public Health Intelligence Network and Champs Public Health Collaborative (Cheshire and Merseyside). It was developed in collaboration with Melisa Campbell, Research Fellow in Public Health, University of Liverpool. For more information & data sources please contact: Janet Ubido, Champs Researcher, Public Health Institute, Liverpool John Moores University. Email: [email protected] 1 Foreword The health and wellbeing of children and young people in our region is a key public health priority. This report presents profiles for children and young people in Cheshire and Warrington to help identify the actions that can support and improve outcomes for this population. The profiles cover a wide range of indicators which all impact upon health and social wellbeing. The first 1000 days from conception and the early years are key stages which impact on children’s health, readiness to grow, learn and succeed. -

87 York Road Brigg North Lincolnshire DN20 8DX Asking Price

The Largest Independent Auction, Estate & Letting Agency in the Region 87 York Road Brigg North Lincolnshire DN20 8DX . Good sized family home in popular location . Lounge with sun room off . Breakfast kitchen & utility . Four bedrooms & bathroom . Off road parking & garage . EPC RATING : D Asking Price: £159,000 Further information and viewings: DDM Residential - Brigg Office - 01652 653666 DESCRIPTION A four bedroom detached family home situated in a popular residential area of Brigg with easy access to the town centre and local schools. The property is decorated to a high standard throughout and briefly comprises entrance hall, lounge with sun room off, breakfast kitchen, utility and cloakroom. To the first floor there are four bedrooms and a family bathroom. Having off road parking, garage and gardens to the front and rear. A good sized family home in excellent location. ACCOMMODATION ENTRANCE HALL uPVC double glazed entrance door, cornice to ceiling, uPVC double glazed window to the front aspect, radiator, stairs to first floor. SITTING ROOM 15' 1'' x 11' 5'' (4.59m x 3.49m) Cornice to ceiling, uPVC double glazed bay window to the front aspect, traditional style painted fire surround with tiled inset and hearth to flame effect electric fire, radiator. SUN ROOM/DINING AREA 14' 0'' x 8' 3'' (4.26m x 2.51m) Cornice to ceiling, uPVC double glazed windows and roof, combination heater/air conditioning unit, tiled floor and uPVC double glazed French doors to the rear garden. BREAKFAST KITCHEN 15' 0'' x 11' 5'' (4.58m x 3.48m) Inset ceiling spot lights, uPVC double glazed windows to the front and rear aspects, range of base and wall mounted units with contrasting beech effect work surfaces, inset one and a half bowl composite sink and drainer with mixer tap, integrated dishwasher and fridge freezer, tiled splashback, black ash effect flooring, archway to: REAR LOBBY Understairs storage cupboard, radiator, black ash effect flooring. -

Cheshire & Warrington

Access to the countryside without the car One issue to which the Forum has not given much attention hitherto is ensuring that the Cheshire countryside is accessible to all residents and visitors irrespective of their means of travel. With increasing attention rightly being given to climate change and the need to cut greenhouse gas emissions, the need for people to be able to reach the countryside easily in a more sustainable way CHESHIRE & than by car perhaps merits being placed higher up the Forum’s agenda. The Forum has a duty to improve public access, and this should extend equally to those who are socially excluded, or who WARRINGTON suffer disability, or who for various reasons either cannot or do not drive a car, as well as car owners who might decide not to drive if The Forum might equally lobby for the introduction of new they are made aware of the other options available. multi-modal tickets, along the lines of the one-time Sunday LOCAL ACCESS FORUM Adventurer Ticket which was valid on buses throughout Cheshire, The two new unitary authorities are responsible for co-ordinating or for the extension of the area of validity of some existing leisure public transport, thus relevant aspects the Forum might press for tickets such as the Wayfarer Ticket, which for almost 30 years has the Councils to consider could include the existence and viability provided a cheap and flexible means of access by bus and rail to of local bus services which provide access to key countryside sites the northern part of the Forum’s area. -

Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England

National Census 2001 and 2011 Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England between 2001 and 2011 East Midlands Region Council for Christian Unity 2014 CONTENTS Foreword from the Chair of the Council for Christian Unity Page 1 Summary and Headlines Page 2 Introduction Page 2 Christian Ethnicity - Comparison of 2001 and 2011 Census Data Page 5 In England Page 5 By region Page 8 Overall trends Page 24 Analysis of Regional data by local authority Page 27 Introduction Page 27 Tables and Figures Page 28 Annex 2 Muslim Ethnicity in England Page 52 Census 2001/2011 East Midlands CCU(14)C3 Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England between 2001 and 2011 Foreword from the Chair of the Council for Christian Unity There are great ecumenical, evangelistic, pastoral and missional challenges presented to all the Churches by the increasing diversity of Christianity in England. The comparison of Census data from 2001 and 2011about the ethnic diversity of the Christian population, which is set out in this report, is one element of the work the Council for Christian Unity is doing with a variety of partners in this area. We are very pleased to be working with the Research and Statistics Department and the Committee for Minority Ethnic Anglican Affairs at Church House, and with Churches Together in England on a number of fronts. We hope that the set of eight reports, for each of the eight regions of England, will be a helpful resource for Church Leaders, Dioceses, Districts and Synods, Intermediate Ecumenical Bodies and local churches. -

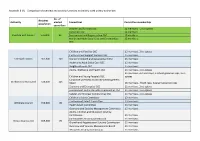

Comparison of Overview and Scrutiny Functions at Similarly Sized Unitary Authorities

Appendix B (4) – Comparison of overview and scrutiny functions at similarly sized unitary authorities No. of Resident Authority elected Committees Committee membership population councillors Children and Families OSC 12 members + 2 co-optees Corporate OSC 12 members Cheshire East Council 378,800 82 Environment and Regeneration OSC 12 members Health and Adult Social Care and Communities 15 members OSC Children and Families OSC 15 members, 2 co-optees Customer and Support Services OSC 15 members Cornwall Council 561,300 123 Economic Growth and Development OSC 15 members Health and Adult Social Care OSC 15 members Neighbourhoods OSC 15 members Adults, Wellbeing and Health OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees 21 members, 4 church reps, 3 school governor reps, 2 co- Children and Young People's OSC optees Corporate Overview and Scrutiny Management Durham County Council 523,000 126 Board 26 members, 4 faith reps, 3 parent governor reps Economy and Enterprise OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Environment and Sustainable Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Safeter and Stronger Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Children's Select Committee 13 members Environment Select Committee 13 members Wiltshere Council 496,000 98 Health Select Committee 13 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee 15 members Adults, Children and Education Scrutiny Commission 11 members Communities Scrutiny Commission 11 members Bristol City Council 459,300 70 Growth and Regeneration Scrutiny Commission 11 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Board 11 members Resources -

NHS North Lincolnshire Clinical Commissioning Group 2014-15

NHS North Lincolnshire Clinical Commissioning Group 2014-15 Annual Report Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…… 1 2. Welcome from the CCG Chair and Chief Officer ………………………………………………………….….. 3 3. Member Practices Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 4. Strategic Report 4.1 About the CCG and its community ……………………………………………………………………….….. 9 4.2 The CCG business model ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 4.3 The CCG strategy ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 4.4 Achievements this year ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 15 4.5 Risks facing the CCG …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 18 4.6 CCG performance …………………………………………………………………………………….…………..….. 19 4.7 The wider context in which the CCG operates …………………………………………………….……. 20 4.8 The CCG’s year-end financial position ………………………………………………………………………. 21 4.9 Going concern ………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….... 22 4.10 Assurance Framework ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 4.11 Sustainability Report ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 27 4.12 Equality and Diversity Report …………………………………………………………………………………. 32 4.13 Key Performance indicators ……………………………………………………………………………………. 36 4.14 Accountable Officer Declaration……………………………………………………………………………… 36 5. The Members’ Report 5.1 The Governing Body ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 37 5.2 Member practices of the CCG ……………………………………………………………………………..…. 38 5.3 Audit Group …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 41 5.4 Committee and Sub-committee membership and Declarations of interest -

Lancashire Dtoc Nov-17

Lancashire DToC Nov-17 Delayed Transfers of Care (DToC) Analysis Lancashire DToC Nov-17 v02 Data Sources Used in this Report DToC All figures relating to the number of delayed days or the number of DToC bed days have been taken from the CSV Format Monthly Delayed Transfers of Care files as published on the NHS website on the second Thursday of each month at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/delayed-transfers-of- care/ Population Rates per 100,000 population for each local authority use the appropriate mid-year estimates for the population aged 18+ as produced by the Office for National Statistics each year. Version Control Document name: Lancashire DToC Nov-17 Version: 02 Date: 12 January 2018 Document control / revision history Version Revision date Summary of changes 01 11/01/2018 02 12/01/2018 Addition of data sources note on page 1 Andrew MacLeod Performance Officer Business Intelligence Lancashire County Council For further information on the work of Business Intelligence, please contact us at: Business Intelligence Lancashire County Council 2nd floor Christ Church Precinct County Hall Fishergate Hill Preston PR1 8XJ E: [email protected] W: www.lancashire.gov.uk/lancashire-insight • 1 • Lancashire DToC Nov-17 v02 Contents 1 Lancashire Overview ..................................................................................... 3 1.1 Lancashire Detail Nov-17 ...................................................................... 3 1.2 Proportions attributable to NHS and social -

STP: Latest Position Developing and Delivering the Humber, Coast and Vale Sustainability and Transformation Plan July 2016 Who’S Involved?

STP: Latest position Developing and delivering the Humber, Coast and Vale Sustainability and Transformation Plan July 2016 Who’s involved? NHS Commissioners Providers Local Authorities East Riding of Yorkshire CCG Humber NHS Foundation Trust City of York Council Hull CCG North Lincolnshire and Goole East Riding of Yorkshire Council NHS Foundation Trust Hull City Council North Lincolnshire CCG Tees, Esk and Wear Valleys North East Lincolnshire CCG NHS Foundation Trust North Lincolnshire Council City Health Care Partnerships North East Lincolnshire Council Scarborough and Ryedale CCG CIC Vale of York CCG Hull and East Yorkshire North Yorkshire County Council Hospitals NHS Trust Navigo Rotherham, Doncaster and South Humber NHS Foundation Trust York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Our footprint Population characteristics 1.4 million population 23% live in the most deprived areas of England Diverse rural, urban and coastal communities Huge variation in health outcomes Three main acute providers Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust North Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Drivers for change • Financial pressures across the system – significant and growing financial deficit across the system, doing nothing is not an option • Average life expectancies across the footprint range widely • Smoking, child and adult obesity rates and excessive alcohol consumption are above (some significantly) national averages • Stroke – our premature mortality rates from stroke are higher than average -

Children and Young People Health and Wellbeing Profile: Cheshire & Warrington Update 2020

Children and Young People Health and Wellbeing Profile: Cheshire & Warrington Update 2020 Public Health Institute, Faculty of Health, Liverpool John Moores University, 3rd Floor Exchange Station Tithebarn Street | Liverpool L2 2QP| [email protected] | www.ljmu.ac.uk/phi IT Y Contents Contents ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Infographic summary ................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Children and young people in Cheshire & Warrington ................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Pre-birth and early years ............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Primary school ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

02/07/2018 – 30/06/2022 Document 1 of 2 Version 4 – May 2019

02/07/2018 – 30/06/2022 Document 1 of 2 Version 4 – May 2019 1 Provider Page ABC Counselling, Play Therapy & Family Solutions C.I.C. 3 ‐ 6 A Time 4 You Child and Family Psychological Services Ltd 7 – 10 Alliance Psychological Services Limited 11 – 14 Barnardo’s 15 – 17 Brook 18 – 21 Children North East 22 – 24 Doorways 25 – 27 MATRIX Neurological 28 – 31 Rainbows End Coaching 32 – 34 Redcar and Cleveland Mind 35 – 37 Tees Valley Therapies 38 – 39 The Junction 40 – 42 The Link CIC 43 – 46 The Wellbeing Centre (Saltburn) CIC 47 – 48 Volunteering Matters 49 – 52 Intervention costs are outlined in a separate document, Schools and RCBC staff can obtain a copy of this by emailing: becky.dale@redcar‐cleveland.gov.uk 2 Name of organisation: ABC Counselling, Play Therapy & Family Solutions C.I.C. Contact name for Peter Lowe MBE or Karen Lowe referrals/enquiries: Email [email protected] ‐ [email protected] Contact Details: Tel 01642 913060 mobile : 07971072789 ‐ 07939922194 Website: www.abccounsellingservices.com Overview of Partnership working services/interventions: ABC Counselling, Play Therapy & Family Solutions and A Time 4 You Psychological Service partnered together to expand reach and share professional expertise and have provided professional counselling and play therapy across over 60 schools in the Tees valley area. We have built up excellent working relationships with key staff, children and importantly Parents to support children and young people to build resilience and use coping strategies through a range of therapeutic interventions, both short and long term, including group work. What we provide Support can be offered to any child or young person with emotional, behavioural or mild to moderate mental health concerns.