Operant/Classical Conditioning: Comparisons, Intersections and Interactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arthur Monrad Johnson Colletion of Botanical Drawings

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7489r5rb No online items Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Processed by Pat L. Walter. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division History and Special Collections Division UCLA 12-077 Center for Health Sciences Box 951798 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1798 Phone: 310/825-6940 Fax: 310/825-0465 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/biomed/his/ ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion 48 1 of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Descriptive Summary Title: Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings, Date (inclusive): 1914-1941 Collection number: 48 Creator: Johnson, Arthur Monrad 1878-1943 Extent: 3 boxes (2.5 linear feet) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Approximately 1000 botanical drawings, most in pen and black ink on paper, of the structural parts of angiosperms and some gymnosperms, by Arthur Monrad Johnson. Many of the illustrations have been published in the author's scientific publications, such as his "Taxonomy of the Flowering Plants" and articles on the genus Saxifraga. Dr. Johnson was both a respected botanist and an accomplished artist beyond his botanical subjects. Physical location: Collection stored off-site (Southern Regional Library Facility): Advance notice required for access. Language of Material: Collection materials in English Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings (Manuscript collection 48). Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division, University of California, Los Angeles. -

Full of Beans: a Study on the Alignment of Two Flowering Plants Classification Systems

Full of beans: a study on the alignment of two flowering plants classification systems Yi-Yun Cheng and Bertram Ludäscher School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA {yiyunyc2,ludaesch}@illinois.edu Abstract. Advancements in technologies such as DNA analysis have given rise to new ways in organizing organisms in biodiversity classification systems. In this paper, we examine the feasibility of aligning two classification systems for flowering plants using a logic-based, Region Connection Calculus (RCC-5) ap- proach. The older “Cronquist system” (1981) classifies plants using their mor- phological features, while the more recent Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV (APG IV) (2016) system classifies based on many new methods including ge- nome-level analysis. In our approach, we align pairwise concepts X and Y from two taxonomies using five basic set relations: congruence (X=Y), inclusion (X>Y), inverse inclusion (X<Y), overlap (X><Y), and disjointness (X!Y). With some of the RCC-5 relationships among the Fabaceae family (beans family) and the Sapindaceae family (maple family) uncertain, we anticipate that the merging of the two classification systems will lead to numerous merged solutions, so- called possible worlds. Our research demonstrates how logic-based alignment with ambiguities can lead to multiple merged solutions, which would not have been feasible when aligning taxonomies, classifications, or other knowledge or- ganization systems (KOS) manually. We believe that this work can introduce a novel approach for aligning KOS, where merged possible worlds can serve as a minimum viable product for engaging domain experts in the loop. Keywords: taxonomy alignment, KOS alignment, interoperability 1 Introduction With the advent of large-scale technologies and datasets, it has become increasingly difficult to organize information using a stable unitary classification scheme over time. -

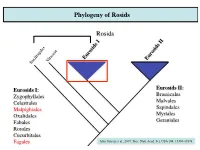

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

List of Plants for Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve Plant Checklist DRAFT as of 29 November 2005 FERNS AND FERN ALLIES Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family) Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum arvense Present in Park Rare Native Field horsetail Vascular Plant Equisetales Equisetaceae Equisetum laevigatum Present in Park Unknown Native Scouring-rush Polypodiaceae (Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Cystopteris fragilis Present in Park Uncommon Native Brittle bladderfern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Dryopteridaceae Woodsia oregana Present in Park Uncommon Native Oregon woodsia Pteridaceae (Maidenhair Fern Family) Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Argyrochosma fendleri Present in Park Unknown Native Zigzag fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cheilanthes feei Present in Park Uncommon Native Slender lip fern Vascular Plant Polypodiales Pteridaceae Cryptogramma acrostichoides Present in Park Unknown Native American rockbrake Selaginellaceae (Spikemoss Family) Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella densa Present in Park Rare Native Lesser spikemoss Vascular Plant Selaginellales Selaginellaceae Selaginella weatherbiana Present in Park Unknown Native Weatherby's clubmoss CONIFERS Cupressaceae (Cypress family) Vascular Plant Pinales Cupressaceae Juniperus scopulorum Present in Park Unknown Native Rocky Mountain juniper Pinaceae (Pine Family) Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies concolor var. concolor Present in Park Rare Native White fir Vascular Plant Pinales Pinaceae Abies lasiocarpa Present -

BM CC EB What Can We Learn from a Tree?

Introduction to Comparative Methods BM CC EB What can we learn from a tree? Net diversification (r) Relative extinction (ε) Peridiscaceae Peridiscaceae yllaceae yllaceae h h atop atop Proteaceae Proteaceae r r Ce Ce Tr oc T ho r M M o de c y y H H C C h r r e e a D D a o o nd o e e G G a a m m t t a a d r P r P h h e e u u c c p A p A r e a a e e a a a c a c n n a i B i B h h n d m d l m a l a m m e a e a e e t t n n c u u n n i i d i i e e e e o n o n p n p n a e a S e e S e e n n x x i i r c c a a n o n o p p h g e h g ae e l r a l r a a a a a a i i a a a e a e i b i b h y d c h d c i y i c a a c x c x c c G I a G I a n c n c c c y l y l t a a t a a e e e e e i l c i l c m l m l e c e c f a e a a f a e a a l r r l c c a i i r l e t e t a a r l a a e e u u u u o a o a a a c a c a a l a l e e e b b a a a a e e c e e c a a s c s c c e l c e l e e g e g e a a a a e e n n s e e s e e e e a a a P a P e e N N u u u S u S a e a e a a e e c c l n a l n e e a e e a e a e a e a e r a r a c c C i C i R R a e a e a e a e r c r c A A a d a a d a e i e i phanopetalaceae s r e ph s r e a a s e c s e c e e u u b a a b a e e P P r r l l e n e a a a a m m entho e e e Ha a H o a c r e c r e nt B B e p e e e c e e c a c c h e a p a a p a lo lo l l a a e s o t e s i a r a i a r r r r r a n e a n e a b a l b t a t gaceae e g e ceae a c a s c s a z e z M i a e M i a c a d e a d e ae e ae r e r a e a e a a a c c ce r e r L L i i ac a Vitaceae Vi r r C C e e ta v e v e a a c a a e ea p e ap c a c a e a P P e e l l e Ge G e e ae a t t e e p p r r ce c an u an -

Supplementary Information

Supporting Information for Cornwell et al. 2014. Functional distinctiveness of major 1 plant lineages. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12208. SUPPORTING INFORMATION Summary In this Supporting Information, we report additional methods details with respect to the trait data, the climate data, and the analysis. In addition, to more fully explain the method, we include several additional figures. We show the top-five lineages, including the population of lineages from which they were selected, for five important traits (Figure S1 on five separate pages); the bivariate distribution of three selected clades with respect to SLA and leaf N, components of the leaf economic spectrum (Figure S2), the geographic distribution of the clades where this proved useful for interpretation (Figure S3); the procedure for selecting the top six nodes in the leaf N trait, to illustrate the internal behavior of our new comparative method, especially the relative contribution of components of extremeness and the sample size weighting to the results (Figure S4). Finally, we provide references for data used in analyses. SUPPORTING METHODS TRAITS DATABASE We compiled a database for five plant functional traits. Each of these traits is the result of a separate research initiative in which data were gathered directly from researchers leading those efforts and/or the literature; in most, but not all cases, these data have been published elsewhere. Detailed methods for data collection and assembly for each trait are available in the original publications; further data were added for some traits from the primary literature (for references see description of individual traits and Supporting References below). For our compilation, all data were brought to common units for a given trait and thoroughly error checked. -

Field Identification of the 50 Most Common Plant Families in Temperate Regions

Field identification of the 50 most common plant families in temperate regions (including agricultural, horticultural, and wild species) by Lena Struwe [email protected] © 2016, All rights reserved. Note: Listed characteristics are the most common characteristics; there might be exceptions in rare or tropical species. This compendium is available for free download without cost for non- commercial uses at http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~struwe/. The author welcomes updates and corrections. 1 Overall phylogeny – living land plants Bryophytes Mosses, liverworts, hornworts Lycophytes Clubmosses, etc. Ferns and Fern Allies Ferns, horsetails, moonworts, etc. Gymnosperms Conifers, pines, cycads and cedars, etc. Magnoliids Monocots Fabids Ranunculales Rosids Malvids Caryophyllales Ericales Lamiids The treatment for flowering plants follows the APG IV (2016) Campanulids classification. Not all branches are shown. © Lena Struwe 2016, All rights reserved. 2 Included families (alphabetical list): Amaranthaceae Geraniaceae Amaryllidaceae Iridaceae Anacardiaceae Juglandaceae Apiaceae Juncaceae Apocynaceae Lamiaceae Araceae Lauraceae Araliaceae Liliaceae Asphodelaceae Magnoliaceae Asteraceae Malvaceae Betulaceae Moraceae Boraginaceae Myrtaceae Brassicaceae Oleaceae Bromeliaceae Orchidaceae Cactaceae Orobanchaceae Campanulaceae Pinaceae Caprifoliaceae Plantaginaceae Caryophyllaceae Poaceae Convolvulaceae Polygonaceae Cucurbitaceae Ranunculaceae Cupressaceae Rosaceae Cyperaceae Rubiaceae Equisetaceae Rutaceae Ericaceae Salicaceae Euphorbiaceae Scrophulariaceae -

Hydrangea Quercifolia Order

Common Name: Oakleaf Hydrangea Scientific Name: Hydrangea quercifolia Order: Rosales Family: Hydrangeaceae Description Oakleaf hydrangea is a deciduous plant. Typically, it loses its leaves in the winter. During the winter season, oakleaf hydrangea will lose all of its leaves and flowers and remain bare until spring. The usual bloom time for oakleaf hydrangea is May-July. When blooming, the flowers are usually white but will change to a purplish-pink color. When describing the plant one must break down into foliage, flower, fruit, and trunk and branches. Oakleaf hydrangea has a simple, ovate shaped leaf with pinnate venation. The oak-like leaves are arranged in opposite pattern. Usual length of the blade is 8-12 inches long. During the fall, the leaves turn purple, but normally the leaves are green. Oakleaf hydrangea has a summer and spring flower with a natural pink coloring. The plant produces flowers in a pyramidal panicle form. The fruit is described as a small, brown oval with a dry, hard covering. Oakleaf hydrangea’s fruit has a diameter less than a half of an inch. Its branches grow in an upright position and have a thick, brown, and multi-stemmed structure. Growth Habit The average height of oakleaf hydrangea is 6-8 feet. The spread in diameter is 6-8 feet. Since it is a multiple stemmed plant, there are several stems that originate from the ground. Oakleaf hydrangea has a fast growth rate of 7 months. Oakleaf hydrangea is a perennial plant, meaning that this plant will be able to grow continuously for many years. -

2 ANGIOSPERM PHYLOGENY GROUP (APG) SYSTEM History Of

ANGIOSPERM PHYLOGENY GROUP (APG) SYSTEM The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, or APG, refers to an informal international group of systematic botanists who came together to try to establish a consensus view of the taxonomy of flowering plants (angiosperms) that would reflect new knowledge about their relationships based upon phylogenetic studies. As of 2010, three incremental versions of a classification system have resulted from this collaboration (published in 1998, 2003 and 2009). An important motivation for the group was what they viewed as deficiencies in prior angiosperm classifications, which were not based on monophyletic groups (i.e. groups consisting of all the descendants of a common ancestor). APG publications are increasingly influential, with a number of major herbaria changing the arrangement of their collections to match the latest APG system. Angiosperm classification and the APG Until detailed genetic evidence became available, the classification of flowering plants (also known as angiosperms, Angiospermae, Anthophyta or Magnoliophyta) was based on their morphology (particularly that of the flower) and their biochemistry (what kinds of chemical compound they contained or produced). Classification systems were typically produced by an individual botanist or by a small group. The result was a large number of such systems (see List of systems of plant taxonomy). Different systems and their updates tended to be favoured in different countries; e.g. the Engler system in continental Europe; the Bentham & Hooker system in Britain (particularly influential because it was used by Kew); the Takhtajan system in the former Soviet Union and countries within its sphere of influence; and the Cronquist system in the United States. -

Appendix 1. Uses and Destination of Species and Landraces Found in the Chagras

Appendix 1. Uses and destination of species and landraces found in the chagras. Chagra Order Family Genus Scientific name Landraces common Uses† Destination‡ names F M N T F SC S N Chagra 1 Poales BROMELIACEAE Ananas Ananas comosus Yellow peel pineapple x x Poales BROMELIACEAE Ananas Ananas comosus Red peel pineapple x x x Poales BROMELIACEAE Ananas Ananas comosus Green peel pineapple x x x Arecales ARECACEAE Euterpe Euterpe precatoria Asaí x x Solanales CONVOLVULACEAE Ipomoea Ipomoea batatas Camote x x Malpighiales EUPHORBIACEAE Manihot Manihot esculenta Flor manioc (sweet) x x x Malpighiales EUPHORBIACEAE Manihot Manihot esculenta Lupuna manioc (bitter) x x x Malpighiales EUPHORBIACEAE Manihot Manihot esculenta Mandioca manioc (bitter) x x x Malpighiales EUPHORBIACEAE Manihot Manihot esculenta Tresmesina manioc x x x (bitter) Malpighiales EUPHORBIACEAE Manihot Manihot esculenta Vega manioc (sweet) x x x Zingiberales MUSACEAE Musa Musa paradisiaca Banana x x x Zingiberales MUSACEAE Musa Musa sp Bellaco plantain x x x Zingiberales MUSACEAE Musa Musa sp Manzana plantain x x x Zingiberales MUSACEAE Musa Musa sp Píldoro/guineo plantain x x x Zingiberales MUSACEAE Musa Musa sp Propio/común plantain x x x Laurales LAURACEAE Persea Persea americana Avocado x x Poales POACEAE Saccharum Saccharum Sugar cane x x x officinarum Malvales MALVACEAE Theobroma Theobroma bicolor Macambo x x -

Scale Insects

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 2015 Scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) found on dracaena and ficus plants (Asparagales: Asparagaceae, Rosales: Moraceae) from southeastern Asia Soo-Jung Suh Animal, Plant and Fisheries Quarantine and Inspection Agency, Busan, KOREA, [email protected] Khanxay Bombay Plant Protection Center Department of Agriculture/MAF Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Entomology Commons Suh, Soo-Jung and Bombay, Khanxay, "Scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) found on dracaena and ficus plants (Asparagales: Asparagaceae, Rosales: Moraceae) from southeastern Asia" (2015). Insecta Mundi. 953. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/953 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0448 Scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) found on dracaena and fi cus plants (Asparagales: Asparagaceae, Rosales: Moraceae) from southeastern Asia Soo-Jung Suh Plant Quarantine Technology Center 476 Dongtanjiseong-ro Yeongtong-gu Suwon, South Korea 443-400 Khanxay Bombay Plant Protection Center Department of Agriculture/MAF Thadeua road KM 13 Vientiane Capital, Lao PDR Date of Issue: October 30, 2015 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Soo-Jung Suh and Khanxay Bombay Scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) found on dracaena and fi cus plants (Asparagales: Asparagaceae, Rosales: Moraceae) from southeastern Asia Insecta Mundi 0448: 1–10 ZooBank Registered: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:74710169-5E50-4D4A-90D7-928575D9D82E Published in 2015 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. -

Floral Structure and Systematics in Four Orders of Rosids, Including a Broad Survey of floral Mucilage Cells

Pl. Syst. Evol. 260: 199–221 (2006) DOI 10.1007/s00606-006-0443-8 Floral structure and systematics in four orders of rosids, including a broad survey of floral mucilage cells M. L. Matthews and P. K. Endress Institute of Systematic Botany, University of Zurich, Switzerland Received November 11, 2005; accepted February 5, 2006 Published online: July 20, 2006 Ó Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract. Phylogenetic studies have greatly ened mucilaginous inner cell wall and a distinct, impacted upon the circumscription of taxa within remaining cytoplasm is surveyed in 88 families the rosid clade, resulting in novel relationships at and 321 genera (349 species) of basal angiosperms all systematic levels. In many cases the floral and eudicots. These cells were found to be most structure of these taxa has never been compared, common in rosids, particulary fabids (Malpighi- and in some families, even studies of their floral ales, Oxalidales, Fabales, Rosales, Fagales, Cuc- structure are lacking. Over the past five years we urbitales), but were also found in some malvids have compared floral structure in both new and (Malvales). They are notably absent or rare in novel orders of rosids. Four orders have been asterids (present in campanulids: Aquifoliales, investigated including Celastrales, Oxalidales, Stemonuraceae) and do not appear to occur in Cucurbitales and Crossosomatales, and in this other eudicot clades or in basal angiosperms. paper we attempt to summarize the salient results Within the flower they are primarily found in the from these studies. The clades best supported by abaxial epidermis of sepals. floral structure are: in Celastrales, the enlarged Celastraceae and the sister relationship between Celastraceae and Parnassiaceae; in Oxalidales, the Key words: androecium, Celastrales, Crossoso- sister relationship between Oxalidaceae and Con- matales, Cucurbitales, gynoecium, Oxalidales.