Parmesan, Cheddar, and the Politics of Generic Geographical Indications (Ggis)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victor Chirkin

30 Crusade. It has become Slow Food’s new hot topic: from this point forth, “sentinels of flavour” will be prohibited from using commercial starter cultures. Along with the “natural cheese” designation, strong philosophical aspirations are emerging—ones that stand the test of the industry’s needs and realities. “Natural” cheeses: going the distance? R D By Débora The theme of this year’s Slow Food Cheese Kefir grains Pereira event (slated to take place in Bra, Italy, from September 15 to 18) is Natural is Possible, advocating cheesemaking without the use of commercial starter cultures. “It is a question of biodiversity preservation,” argues Piero Sardo, President of the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity. “Nowadays, everyone is using the same starter cultures, thereby erasing the ability to link a cheese to its terroir. Moreover, it is a matter of survival for small farmers. I am surprised,” he points out, “by how difficult it is for the French to Methods address this issue.” He believes that there is There are four no logic to working with raw milk if you are main methods to going to use commercial starter cultures. cultivate starter However, apart from the Brousse du Rove, cultures at home: most French “sentinel” cheeses, such as Salers backslopping Tradition, Laguiole, and the cheeses of the whey from one summer pastures of the Basque Pyrenees, cheese to make resort to exogenous starter cultures, at least to Marie-Christine Montel, a retired microbiologist another (such as kick off the season. of INRA’s Aurillac cheese facility, remembers how the Salers AOP (protected designation of with farmstead • Backslopping origin) greatly benefited from the introduction of lactic chevres) commercial starter cultures since, at the time, it backslopping provided solutions to manufacturing problems The main challenge for those who engage in on fermented such as post-acidification. -

LATTERIA OVARO Nasce a 525 Metri D’Altitudine Nel Caseificio Di Ovaro, Da Cui Prende Il Nome Carnico Di “Davar”

FORMAGGI INDICE FORMAGGI DELLA LATTERIA DI OVARO Pag. 1 FORMAGGI DEL FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA Pag. 7 FORMAGGI NAZIONALI Pag. 17 FORMAGGI REGIONALI Pag. 30 FORMAGGI FRESCHI Pag. 54 FORMAGGI ESTERI Pag. 61 LATTERIA OVARO Nasce a 525 metri d’altitudine nel caseificio di Ovaro, da cui prende il nome carnico di “Davar”. È proprio la montagna a segnare il carattere di questo formaggio latteria che si presenta con una pasta leggermente occhiata ed un colore paglierino che aumenta, assieme al gusto, con l’avanzare della stagionatura. Ideale la versione con una maturazione dai 4 ai 6 mesi. Peso per pezzo: 6,50 kg Pezzi per cartone: 2 Stagionatura: 30-60-90-120-mezzano MONTASIO DOP PDM (Prodotto Della Montagna) Il Montasio prodotto nel caseificio di Ovaro è l’unico Montasio prodotto in Friuli che, secondo le direttive del consorzio, può fregiarsi della denominazione PDM (Prodotto Della Montagna), in quanto ha la peculiarità di essere prodotto e stagionato in un caseificio ad oltre 500 metri di altitudine, con latte proveniente da zone oltre i 500 metri. Il sapore, morbido e delicato quando è fresco si fa via via più deciso ed aromatico. La pasta, da bianca compatta con una caratteristica occhiatura omogenea ed una crosta liscia ed elastica, con il passare dei mesi diventa granulosa e friabile con una crosta secca e più scura. Forma cilindrica, altezza 6-10 cm, larghezza 30-40 cm. Peso per pezzo: 6,5 kg Pezzi per cartone: 2 Stagionatura: 60-90-120-mezzano-oltre 12 mesi-oltre 18 mesi. MONTASIO DOP 047 Ha diverse facce, trasforma il suo gusto, sorprende per la sua varietà e accontenta tutti i palati. -

45 Fromages, 3 Beurres, 2 Crèmes. Appellation D

45 FROMAGES, 3 BEURRES, 2 CRÈMES. APPELLATION D’ORIGINE PROTÉGÉE LES AOP, PREUVES DE GARANTIES ET PROTECTIONS FORTES Origine de toutes les étapes de fabrication. Une fabrication dans la zone de production (production du lait, transformation et affinage), c’est la re1 garantie apportée par une AOP. Protection contre les usurpations. Un produit bénéficiant d’une appellation ne peut être copié ! Ainsi, il ne peut exister de reblochon qui ne serait pas AOP ! De même, tous les cantals sont AOP et ainsi de suite, il ne peut en être autrement ! Préservation des savoir-faire. Parce que n’importe qui ne peut pas faire des AOP n’importe comment, toutes les étapes d’obtention d’une AOP sont strictement définies dans un cahier des charges rigoureusement contrôlé par un organisme certificateur indépendant. Participation à l’économie de nos territoires. Les AOP dynamisent l’activité économique de régions souvent contrai- gnantes pour la production agricole. Transparence totale. Dans les AOP, rien n’est caché, tout est écrit net, sans ambiguïté dans le cahier des charges. Diversité des saveurs. Choisir un fromage, beurre ou crème AOP, c’est choisir parmi 50 produits eux-mêmes diversifiés dans leurs saveurs, à l’image de la richesse des hommes et du terroir de chacun des produits. Ne pas proposer des goûts standardisés, c’est aussi une promesse des AOP. 1 11 RÉGIONS DE PRODUCTION DES FROMAGES, BEURRES ET CRÈMES AOP 7 11 5 4 3 8 10 2 9 1 6 2 SOMMAIRE Valeurs AOP p. 1 7 NORMANDIE 1 AQUITAINE MIDI-PYRENÉES • Camembert de Normandie p. -

CFIA/ ACIA # CFIA Dairy Products ACIA Produits Laitiers Butter

CFIA/ CFIA Dairy Products ACIA Produits laitiers ACIA # Butter - Beurre 100 100 - 001 BUTTER BEURRE 100 - 002 WHEY BUTTER BEURRE DE LACTOSÉRUM 100 - 003 BUTTER CUTTING COUPAGE DE BEURRE SEULEMENT 100 - 004 DAIRY SPREAD AND WHIPPED DAIRY TARTINADE LAITIÈRE ET TARTINADE SPREAD LAITIÈRE 100 - 005 CALORIE REDUCED BUTTER FOUETTE 100 - 006 LITE BUTTER BEURRE RÉDUIT EN CALORIES / BEURRE LÉGER 100 - 007 WHIPPED BUTTER BEURRE FOUETTÉ 100 - 008 BUTTER REDDIES, PATTIES, CUPS BEURRE EN PLAQUETTES, BARQUETTES AND MICROPRINTS ET MICROPAINS 100 - 009 BUTTER OIL HUILE DE BEURRE 100 - 010 ANHYDROUS BUTTER OIL HUILE DE BEURRE ANHYDRE 100 - 011 FLAVOURED BUTTERS BEURRES ASSAISONNÉS Cheese - Fromage 200 200 - 001 CHEDDAR CHEESE FROMAGE CHEDDAR 200 - 002 ALPINA CHEESE FROMAGE ALPINA 200 - 003 ASIAGO CHEESE FROMAGE ASIAGO 200 - 004 BLUE CHEESE FROMAGE BLEU 200 - 005 BOCCONCINI CHEESE FROMAGE BOCCONCINI 200 - 006 BUTTER CHEESE (BUTTIRI) FROMAGE BUTIRRO 200 - 007 BRA AND NEW BRA CHEESE FROMAGE BRA ET NOUVEAU BRA 200 - 008 BRICK CHEESE FROMAGE BRICK 200 - 009 BRIE CHEESE FROMAGE BRIE 200 - 010 CACIOCAVALLO CHEESE FROMAGE CACIOCAVALLO 200 - 011 CACIOTTA CHEESE FROMAGE CACIOTTA 200 - 012 CAMEMBERT CHEESE FROMAGE CAMEMBERT 200 - 013 COLBY CHEESE FROMAGE COLBY 200 - 014 COOK CHEESE FROMAGE COOK 200 - 015 COULOMMIERS CHEESE FROMAGE COULOMMIERS 200 - 016 CREAM CHEESE FROMAGE A LA CRÈME 200 - 017 DANBO CHEESE FROMAGE DANBO 200 - 018 DRY RICOTTA CHEESE FROMAGE RICOTTA SEC 200 - 019 EDAM CHEESE FROMAGE EDAM 200 - 020 EMMENTALER (EMMENTAL) CHEESE FROMAGE EMMEMTAL 200 - -

Guided by Travel 2016 - 2017

europe guided by travel 2016 - 2017 up Save to $ per300 person† (see back cover for details) – The best TRAVEL PROTECTION PLAN in the industry! – Private SEDAN SERVICE included! (See inside for details.) Untitled-1 1 1/7/16 11:23 AM table of contents Introduction ....................................................... 2 - 21 Central & Eastern Europe Italy Alpine Lakes & Scenic Trains ........................... 114, 115 L Italian Vistas ..................................................... 22, 23 Discover Switzerland, Austria & Bavaria .......... 116, 117 Reflections of Italy ............................................ 24, 25 Exploring the Alpine Countries ......................... 118, 119 e Italy’s Treasures ................................................ 26, 27 Discover Croatia, Slovenia and the Adriatic Coast .. 120, 121 e Tuscan & Umbrian Countryside ........................ Discovering Poland ......................................... 122, 123 28, 29 L Discover Tuscany ............................................. 30, 31 Imperial Cities ................................................... 124, 125 Tuscany & the Italian Riviera ............................. 32, 33 Magnificent Cities of Central Spotlight on Rome ........................................... 34, 35 & Eastern Europe ............................................ 126, 127 Spotlight on Venice in Winter ........................... 36, 37 Rome & the Amalfi Coast ................................. 38, 39 River Cruises & Holiday RC Venice, Florence and Rome ........................... -

Scandinavian Cheeses Malcom Jarvis Quesodiego Cheese Club, 19 February 2013

Scandinavian Cheeses Malcom Jarvis QuesoDiego Cheese Club, 19 February 2013 Scandinavia is a historical region in Northern Europe characterized by a common ethno- cultural Germanic heritage and related languages. This region encompasses three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Modern Norway and Sweden proper are situated on the Scandinavian Peninsula, whereas modern Denmark is situated on the Danish islands and Jutland. Sometimes the term Scandinavia is also taken to include Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Finland, on account of their historical association with the Scandinavian countries. Such usage, however, may be considered inaccurate in the area itself, where the term Nordic countries instead refers to this broader group. The vast majority of the human population of Scandinavia are Scandinavians, descended from several (North) Germanic tribes who originally inhabited the southern part of Scandinavia and what is now northern Germany, who spoke a Germanic language Pairing wines and cheeses from the same region is a good, “safe” place to start wine and cheese combinations. Unfortunately, the Scandinavian countries do not make any good wine that I am aware of. Cheeses Of Norway Gammelost It is a traditional Norwegian ripened table cheese with irregular blue veins made principally in the counties of Hardanger and Sogn. It is rich in protein with low fat content, measuring 1% fat and 50% protein. Moisture, not more than 52 percent (usually 46 to 52 percent) ash, 2.5 percent; and salt (in the ash), 1 percent Its name translates as "old cheese" because the rind grows a mould that makes it look old before its time. -

Le Aziende Partecipanti All'edizione 2019

Le aziende partecipanti all’edizione 2019 4 MADONNE CASEIFICIO DELL’EMILIA AIXTRA, S.C. Strada Lesignana, 130 Goikotxe, 12 - Bajo A 41123 Lesignana (MO) 01250 Araya (Araba) Tel. 059/849468 Spagna Fax 059/849468 Tel. 0034 620 911484 E-mail: [email protected] In Concorso: Idiazabal DOP Aixtra In Concorso: Parmigiano Reggiano DOP (24 Mesi) AIZPEA, E.Z. Aizpea Baserria 20212 Olaberria (Gipuzkoa) A & A FORMAGGI S.N.C. Spagna Via Casale di Sant’Angelo, 28 Tel. 0034 615 763131 00061 Anguillara Sabazia (RM) In Concorso: Idiazabal DOP Aizpea Tel. 06/99849207 E-mail: [email protected] ALAN FARM SOCIETÀ AGRICOLA In Concorso: Caciocardo; Caciotta Serafino; F.LLI ANDRIOLLO E FIGLI S.S. Ricotta Adriani; Caciolimone Via Migliara 51 Sx, 167 04014 Pontinia (LT) Tel. 0773/850147 AGASUR, S.C.A. E-mail: [email protected] C/ Limitación, 14 Web: www.caseificioalanfarm.com Polígono Industrial La Huertecilla In Concorso: Mozzarella Vaccina; Caciottone 29196 Málaga (Málaga) Morbido; Provolone Stagionato; Ricotta Spagna Vaccina Tel. 0034 952 179311 Fax 0034 952 179709 ALCHIMISTA LACTIS E-mail: [email protected] Via Sacrofano-Cassia, 4050 Web: www.quesoselpinsapo.com 00060 Sacrofano (RM) In Concorso: Queso Gran Reserva El Pinsapo Tel. 388/4678439 E-mail: [email protected] In Concorso: Stracchinato dell’Alchimista; AGRICOLTURA NUOVA S.C.S.A.I. Caciotta Gajarda; Ricotta alla Vecchia Via Valle di Perna, 315 Maniera; Ebriosus; Tufarina Veia 00128 Roma Tel. 06/5070453 ANDRE JUUSTUFARM OÜ E-mail: [email protected] Kambja Parisk, Talvikase Village Web: www.agricolturanuova.it 62028 Tartumaa In Concorso: Primo Sale; Pecorino Estonia Semistagionato; Pecorino Stagionato Extra; Tel. -

Technological Strategies to Preserve Burrata Cheese Quality

coatings Article Technological Strategies to Preserve Burrata Cheese Quality Cristina Costa 1, Annalisa Lucera 1, Amalia Conte 1,*, Angelo Vittorio Zambrini 2 and Matteo Alessandro Del Nobile 1 1 Department of Agricultural Sciences, Food and Environment, University of Foggia, Via Napoli, 25–71122 Foggia, Italy; [email protected] (C.C.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (M.A.D.N.) 2 Department of Quality, Innovation, Safety, Environment, Granarolo S.p.A., Via Cadriano, 27/2–40127 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-881-589-240 Received: 4 May 2017; Accepted: 4 July 2017; Published: 9 July 2017 Abstract: Burrata cheese is a very perishable product due to microbial proliferation and undesirable sensory changes. In this work, a step-by-step optimization approach was used to design proper processing and packaging conditions for burrata in brine. In particular, four different steps were carried out to extend its shelf life. Different headspace gas compositions (MAP-1 30:70 CO2:N2; MAP-2 50:50 CO2:N2 and MAP-3 65:35 CO2:N2) were firstly tested. To further promote product preservation, a coating was also optimized. Then, antimicrobial compounds in the filling of the burrata cheese (lysozyme and Na2-EDTA) and later in the coating (enzymatic complex and silver nanoparticles) were analyzed. To evaluate the quality of the samples, in each step headspace gas composition, microbial population, and pH and sensory attributes were monitored during storage at 8 ± 1 ◦C. The results highlight that the antimicrobial compounds in the stracciatella, coating with silver nanoparticles, and packaging under MAP-3 represent effective conditions to guarantee product preservation, moving burrata shelf life from three days (control sample) to ten days. -

Microbiological Risk Assessment of Raw Milk Cheese

Microbiological Risk Assessment of Raw Milk Cheese Risk Assessment Microbiology Section December 2009 MICROBIOLOGICAL RISK ASSESSMENT OF RAW MILK CHEESES ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................. VII ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................. VIII 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................. 1 2. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................... 8 3. PURPOSE AND SCOPE ..................................................................................................... 9 3.1 PURPOSE...................................................................................................................... 9 3.2 SCOPE .......................................................................................................................... 9 3.3 DEFINITION OF RAW MILK CHEESE ............................................................................... 9 3.4 APPROACH ................................................................................................................ 10 3.5 OTHER RAW MILK CHEESE ASSESSMENTS .................................................................. 16 4. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 18 4.1 CLASSIFICATION -

Cheese-Tek ®

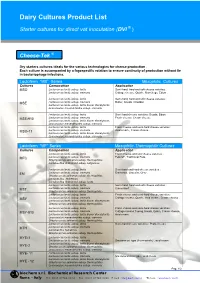

Dairy Cultures Product List Starter cultures for direct vat inoculation (DVI ® ) Cheese-Tek ® Dry starters cultures ideals for the various technologies for cheese production . Each culture is accompanied by a fagospecific rotation to ensure continuity of production without lie in bacteriophage infections. Lactoferm “MS” Series Mesophilic Cultures Cultures Composition Application MSO Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis Semi-hard, hard and soft cheese varieties : Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Cottage cheese, Quark, Manchego, Edam . Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis Semi-hard, hard and soft cheese varieties : MSE Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Butter, Gouda, Cheddar . Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis Semi-hard cheese varieties: Gouda, Edam MSE-910 Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Fresh cheese: Cream cheese Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis Fresh cheese and semi-hard cheese varieties : MSO-11 Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Acid cream , Cream cheese . Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar diacetylactis Leuconostoc mesenteroides subsp. cremoris Lactoferm “MF” Series Mesophilic-Thermophilic Cultures Cultures Composition Application Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis Fresh cheese and soft cheese varieties : MFC Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris Feta UF, Traditional Feta, Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. -

Wholesale Cheese Catalogue 201 9

W H O L E S A L E CH E E S E C A T A L O G U E 201 9 CHEFSG ARDEN.NET TABLE OF CONTENT ABOUT US 02 SPANISH 40 SHEEPS’ CHEESE 40 AUSTRALIAN 04 COWS’ CHEESES 04 BRITISH 42 WHITE MOULD 04 COWS’ CHEESES 42 CHEDDAR 06 SOFT 42 BLUE VEIN 07 CHEDDAR 44 FETTA 08 HARD 46 HALOUM I 10 BLUE 49 FRUIT 11 G OATS’ CHEESES 51 MARIN A TED FET TA BLUE 52 BOCCONCINI 12 EWES’ CHEESE 53 MOZZARELLA 13 BLUE CHEESE S 54 SOFT CHEESE 17 CACIOTTA & PECORINO 19 IRISH 56 SMOKED CHEESES 21 COWS’ CHEESES 56 23 MATURED CHEESES GOATS’ CHEESES 57 BUFFALOS’ CHEESE 25 EWES’ CHEESES 58 SMOKED CHEESES 26 INDIVIDUAL & PORTION 60 COWS’ CHEESES 60 FRENCH 28 CHEDDAR 60 GOATS’ CHEESES 28 BLUE 62 COWS’ CHEESES 29 SOFT 63 EWES’ CHEESES 34 HARD 66 B LUE CHEESE S 34 GOATS’ CHEESES 67 CRACKERS 69 ITALIAN 36 COWS’ CHEESES 36 FRUIT PASTES 70 BLUE CHEESE S 38 ABOUT CHEF’S GARDEN LTD Established in 1999, Chef’s Garden has been supplying an extensive range of fresh and frozen produce from Australia, Europe, United States and the PRC. Our extensive range includes chilled meat, seafood, fruit and vegetables and dry goods. We are firmly positioned as the preferred supplier to some for the leading restaurants, five star hotels, and some of Hong Kong’s favourite food and beverage outlets. Order can be placed by fax, phone or on-line. Order any time before 3am for same morning delivery. -

2020-07-03 Cheese/Item List

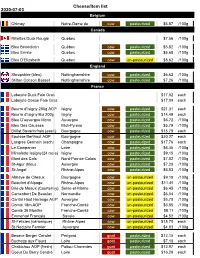

Cheese/Item list 2020-07-03 Belgium Chimay Notre-Dame de cow pasteurized $6.87 /100g Canada Rillettes Duck Rougié Québec $7.56 /100g Bleu Bénédictin Québec cow pasteurized $5.82 /100g Bleu Ermite Quebec cow pasteurized $5.68 /100g Bleu D'Elizabeth Quebec cow un-pasteurized $8.62 /100g England Shropshire (bleu) Nottinghamshire cow pasteurized $6.62 /100g Stilton Coltson Basset Nottinghamshire cow pasteurized $7.26 /100g France Labeyrie Duck Foie Gras $17.02 each Labeyrie Goose Foie Gras $17.09 each Beurre d'Isigny 250g AOP Isigny cow pasteurized $21.31 each Beurre d'Isigny Bio 200g Isigny cow pasteurized $14.49 each Bleu D'auvergne Morin Auvergne cow pasteurized $6.72 /100g Bleu Des Causses Midi-Pyrene cow pasteurized $5.79 /100g Brillat Savarin frais (each) Bourgogne cow pasteurized $15.78 each Epoisse Berthaut AOP Bourgogne cow pasteurized $30.27 each Langres Germain (each) Champagne cow pasteurized $17.76 each Le Campanier Loire cow pasteurized $6.45 /100g Mimolette Issigny(24 mois) Isigny cow pasteurized $9.15 /100g Mont des Cats Nord-Pas-de-Calais cow pasteurized $7.02 /100g St-Agur (bleu) Auvergne cow pasteurized $7.29 /100g St-Angel Rhône-Alpes cow pasteurized $6.53 /100g Abbaye de Citeaux Bourgogne cow un-pasteurized $9.18 /100g Beaufort d'Alpage Rhône-Alpes cow un-pasteurized $11.49 /100g Brie de Meaux (Courtenay) Seine-et-Marne cow un-pasteurized $6.45 /100g Camenbert De Beaulac Normandie cow un-pasteurized $6.54 /100g Cantal Haut Herbage AOP Auvergne cow un-pasteurized $5.70 /100g Comté 18m AOP Franche-Comté cow un-pasteurized