Establishing Roman Rule in Egypt: the Trilingual Stela of C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the D

The Politics of Roman Memory in the Age of Justinian DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Marion Woodrow Kruse, III Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2015 Dissertation Committee: Anthony Kaldellis, Advisor; Benjamin Acosta-Hughes; Nathan Rosenstein Copyright by Marion Woodrow Kruse, III 2015 ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the use of Roman historical memory from the late fifth century through the middle of the sixth century AD. The collapse of Roman government in the western Roman empire in the late fifth century inspired a crisis of identity and political messaging in the eastern Roman empire of the same period. I argue that the Romans of the eastern empire, in particular those who lived in Constantinople and worked in or around the imperial administration, responded to the challenge posed by the loss of Rome by rewriting the history of the Roman empire. The new historical narratives that arose during this period were initially concerned with Roman identity and fixated on urban space (in particular the cities of Rome and Constantinople) and Roman mythistory. By the sixth century, however, the debate over Roman history had begun to infuse all levels of Roman political discourse and became a major component of the emperor Justinian’s imperial messaging and propaganda, especially in his Novels. The imperial history proposed by the Novels was aggressivley challenged by other writers of the period, creating a clear historical and political conflict over the role and import of Roman history as a model or justification for Roman politics in the sixth century. -

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the Office of the Praetor Prefect Of

Book I. Title XXVII. Concerning the office of the Praetor Prefect of Africa and concerning the whole organization of that diocese. (De officio praefecti praetorio Africae et de omni eiusdem dioeceseos statu.) Headnote. Preliminary. For a better understanding of the following chapters in the Code, a brief outline of the organization of the Roman Empire may be given, but historical works will have to be consulted for greater details. The organization as contemplated in the Code was the one initiated by Diocletian and Constantine the Great in the latter part of the third and the beginning of the fourth century of the Christian era, and little need be said about the time previous to that. During the Republican period, Rome was governed mainly by two consuls, tow or more praetors (C. 1.39 and note), quaestors (financial officers and not to be confused with the imperial quaestor of the later period, mentioned at C. 1.30), aediles and a prefect of food supply. The provinces were governed by ex-consuls and ex- praetors sent to them by the Senate, and these governors, so sent, had their retinue of course. After the empire was established, the provinces were, for a time, divided into senatorial and imperial, the later consisting mainly of those in which an army was required. The senate continued to send out ex-consuls and ex-praetors, all called proconsuls, into the senatorial provinces. The proconsul was accompanied by a quaestor, who was a financial officer, and looked after the collection of the revenue, but who seems to have been largely subservient to the proconsul. -

RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian's “Great

ABSTRACT RICE, CARL ROSS. Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy. (Under the direction of Prof. S. Thomas Parker) In the year 303, the Roman Emperor Diocletian and the other members of the Tetrarchy launched a series of persecutions against Christians that is remembered as the most severe, widespread, and systematic persecution in the Church’s history. Around that time, the Tetrarchy also issued a rescript to the Pronconsul of Africa ordering similar persecutory actions against a religious group known as the Manichaeans. At first glance, the Tetrarchy’s actions appear to be the result of tensions between traditional classical paganism and religious groups that were not part of that system. However, when the status of Jewish populations in the Empire is examined, it becomes apparent that the Tetrarchy only persecuted Christians and Manichaeans. This thesis explores the relationship between the Tetrarchy and each of these three minority groups as it attempts to understand the Tetrarchy’s policies towards minority religions. In doing so, this thesis will discuss the relationship between the Roman state and minority religious groups in the era just before the Empire’s formal conversion to Christianity. It is only around certain moments in the various religions’ relationships with the state that the Tetrarchs order violence. Consequently, I argue that violence towards minority religions was a means by which the Roman state policed boundaries around its conceptions of Roman identity. © Copyright 2016 Carl Ross Rice All Rights Reserved Diocletian’s “Great Persecutions”: Minority Religions and the Roman Tetrarchy by Carl Ross Rice A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of North Carolina State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Raleigh, North Carolina 2016 APPROVED BY: ______________________________ _______________________________ S. -

The Coinage System of Cleopatra Vii, Marc Antony and Augustus in Cyprus

1 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS By Matthew Kreuzer 2 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS By Matthew Kreuzer Second Edition Springfield, Mass. Copyright Matthew Kreuzer 2000-2009. 3 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Contents Summary 5 Historical Background 9 Coins Circulating in Cleopatra’s Cyprus 51-30 BC 10 What Were the Denominations in Cleopatra’s Cyprus? 12 The Tetradrachm 13 The Drachm 28 The Full-Unit 29 The Half-Unit 35 The Quarter-Unit 39 The Eighth-Unit 41 The Tiny Sixteenth-Unit 45 Other Small Late Ptolemaic Bronzes 48 Archeological Context – A Late Ptolemaic Bronze Mint 50 Making Small Change 53 Relationship Between the Denominations 55 Circulating Earlier Ptolemaic and Foreign Coinage 56 Cypriot Bronze of Cleopatra, After Actium 58 Silver denarii of Marc Antony, 37-30 BC 61 Cypriot Coinage Under Augustus, 30-22 BC 69 Cypriot Bronze of Augustus, CA coinage 70 Non-Export Obols and Quadrans 75 Silver Quinarii and Denarii of Augustus, 28-22 BC 78 Cyprus as a Senatorial Province under Augustus, 22 BC to 14 AD 87 Cypriot Coinage under Tiberius and Later, After 14 AD 92 Table of Suggested Attribution Changes 102 Appendix I - Analysis of Declining Obol Weight Standard 121 Appendix II - Octavia or Cleopatra? Credits and Bibliography 139 4 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS "If the nose of Cleopatra had been a little shorter, the whole face of the world would have been changed." Blaise Pascal 5 / 140 THE COINAGE SYSTEM OF CLEOPATRA VII, MARC ANTONY AND AUGUSTUS IN CYPRUS Summary During the late reign of Cleopatra VII a cornucopia of coinage circulated in Cyprus. -

A Sketch of the Geography and History of Egypt

A SKETCH OF THE GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY OF EGYPT EGYPT, situated in the northeastern corner of Africa, is a small country, if compared with the huge continent of which it forms a part; its size about equals that of the state of Maryland. And yet it has produced one of the greatest civilizations of the world. Egypt is the land on both sides of the lower part of the river Nile, from the town of Assuan (Syene) at the First Cataract (i.e. rapids) down to the Mediterranean Sea. Nature herself has divided the country into two different parts: the narrow stretches of fertile land adjoining the river from Assuan down to the region of modern Cairo--which we call "Upper Egypt" or the "Sa'id"- and the broad triangle, formed in the course of millennia from the silt deposited by the river where it flows into the Mediterranean. This we call "Lower Egypt" or the "Delta." In the course of history, a number of towns and cities have sprung up along the Upper Nile and its branches in the Delta. The two most impor- tant cities in antiquity were Memphis in the north and Thebes in the south. The site of Memphis, not far south of modern Cairo, is largely covered by palm groves today. At Thebes the remains of the temples of Amon, named after the neighboring villages of Karnak and Luxor, are still imposing witnesses of bygone greatness and splendor. The only other sites I shall mention are those from which specimens in our collection have come. -

2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced - - - Times

Westminster School Simsbury, CT 06070 www.westminster-school.org Saturday, May 8, 2021 Vol. 110 No. 8 2021-2022 Prefect Board Introduced COMPILED BY ALEYNA BAKI ‘21, MATTHEW PARK ‘21 & HUDSON STEDMAN ‘21 CO-EDITORS-IN-CHIEF, 2020-2021 Head Prefect Junior Prefect Cooper Kistler is a boarder from Bella Tawney is a day student Tiburon, CA. He is a member of John Hay, from Simsbury, CT. She is a member of Black & Gold, First Boys’ Basketball, and John Hay, Black & Gold, the SAC Board, a Captain of First Boys’ lacrosse. As the new Captain of First Girls’ Basketball and First Head Prefect, Cooper aims to be the voice Girls’ Cross Country, as well as a Horizons of everyone in the community to cultivate a volunteer, the Co-President of AWARE, and culture of growth by celebrating the diver- a HOTH board member. In her final year sity of perspectives in the community. on the Hill, she is determined to create an In his own words: “I want to be the environment, where each and every member middleman between the Students and the of the school community feels accepted. Administration. I want to share the new In her own words: “The past year has perspective that we have all established dur- posed a number of difficulties, and it is ing the pandemic, and use it for the better. hard to adapt, but we should take this as an I want to UNITE the NEW school com- opportunity to teach our community and munity." continue to make it our Westminster." Priscilla Ameyaw is a Sung Min Cho is a Margot Douglass is a boarder from Ghana. -

Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs the Ptolemaic Family In

Department of World Cultures University of Helsinki Helsinki Macedonian Kings, Egyptian Pharaohs The Ptolemaic Family in the Encomiastic Poems of Callimachus Iiro Laukola ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XV, University Main Building, on the 23rd of September, 2016 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2016 © Iiro Laukola 2016 ISBN 978-951-51-2383-1 (paperback.) ISBN 978-951-51-2384-8 (PDF) Unigrafia Helsinki 2016 Abstract The interaction between Greek and Egyptian cultural concepts has been an intense yet controversial topic in studies about Ptolemaic Egypt. The present study partakes in this discussion with an analysis of the encomiastic poems of Callimachus of Cyrene (c. 305 – c. 240 BC). The success of the Ptolemaic Dynasty is crystallized in the juxtaposing of the different roles of a Greek ǴdzȅǻǽǷȏȄ and of an Egyptian Pharaoh, and this study gives a glimpse of this political and ideological endeavour through the poetry of Callimachus. The contribution of the present work is to situate Callimachus in the core of the Ptolemaic court. Callimachus was a proponent of the Ptolemaic rule. By reappraising the traditional Greek beliefs, he examined the bicultural rule of the Ptolemies in his encomiastic poems. This work critically examines six Callimachean hymns, namely to Zeus, to Apollo, to Artemis, to Delos, to Athena and to Demeter together with the Victory of Berenice, the Lock of Berenice and the Ektheosis of Arsinoe. Characterized by ambiguous imagery, the hymns inspect the ruptures in Greek thought during the Hellenistic age. -

Quipment of Georgios Maniakes and His Army According to the Skylitzes Matritensis

ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑ da un’idea di Nicola Bergamo “Saranno come fiori che noi coglieremo nei prati per abbellire l’impero d’uno splendore incomparabile. Come specchio levigato di perfetta limpidezza, prezioso ornamento che noi collocheremo al centro del Palazzo” La prima rivista on-line che tratta in maniera completa il periodo storico dei Romani d’Oriente Anno 2005 Dicembre Supplemento n 4 A Prôtospatharios, Magistros, and Strategos Autokrator of 11th cent. : the equipment of Georgios Maniakes and his army according to the Skylitzes Matritensis miniatures and other artistic sources of the middle Byzantine period. a cura di: Dott. Raffaele D’Amato A Prôtospatharios, Magistros, and Strategos Autokrator of 11th cent. the equipment of Georgios Maniakes and his army according to the Skylitzes Matritensis miniatures and other artistic sources of the middle Byzantine period. At the beginning of the 11th century Byzantium was at the height of its glory. After the victorious conquests of the Emperor Basil II (976-1025), the East-Roman1 Empire regained the sovereignty of the Eastern Mediterranean World and extended from the Armenian Mountains to the Italian Peninsula. Calabria, Puglia and Basilicata formed the South-Italian Provinces, called Themata of Kalavria and Laghouvardhia under the control of an High Imperial Officer, the Katepano. 2But the Empire sought at one time to recover Sicily, held by Arab Egyptian Fatimids, who controlled the island by means of the cadet Dynasty of Kalbits.3 The Prôtospatharios4 Georgios Maniakes was appointed in 1038 by the -

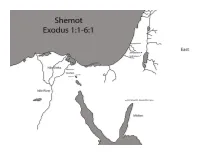

Shemot Map Updated.Pdf

Mapping the Portion In Torah Portion Shemot, we have a lot of traveling to do! You will need 3 colors to complete this map: red, blue and green. You can use whichever medium you wish: crayons, pencils or markers. Mapping can be done as you reach each verse in your portion, or as a separate activity. The goal of mapping is to familiarize yourself with the geography of the land, to visualize where important Biblical events happened and to bring Bible history to life! Genesis 47:27 Israelites living in Goshen Color the area around Goshen in BLUE, including Rameses and Pithom Exodus They built Pithom and Rameses as store cities for 1:11 Pharoah Exodus Every boy that is born you must throw into the 1:22 Nile Outline the Nile in RED Exodus But Moses fled from Pharaoh and went to live in 2:15 Midian Draw a path from Ramses to Midian in GREEN [Moses] led the flock to the far side of the desert Exodus and came to Horeb, the mountain of YHVH 3:1 (God) Draw a path to Mt. Sinai* in GREEN Exodus 4:18 Moses went back to Jethro Draw a path back to Midian in GREEN Exodus [Aaron] met Moses at the Mountain of YHVH 4:27 (God) Draw a path back to Mt. Sinai in GREEN Exodus 4:29 Met with Elders (in Egypt) Draw a path back to Rameses in GREEN Circle Jerusalem in RED. Draw a line in GREEN from the East to Jerusalem. You can start from Matthew Wise men from the East arrive in Jerusalem the edge of the page or at the word “East”- since we are not exactly sure where in they East they 2:1 looking for Yeshua (Jesus) came from! Matthew 2:8 Wise men travel to Bethlehem Circle Bethlehem in BLUE and draw a line in GREEN connecting Jerusalem to Bethlehem The map provided was created based on our best research. -

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome William E. Dunstan ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC. Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK ................. 17856$ $$FM 09-09-10 09:17:21 PS PAGE iii Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright ᭧ 2011 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. All maps by Bill Nelson. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. The cover image shows a marble bust of the nymph Clytie; for more information, see figure 22.17 on p. 370. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dunstan, William E. Ancient Rome / William E. Dunstan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7425-6832-7 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6833-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-7425-6834-1 (electronic) 1. Rome—Civilization. 2. Rome—History—Empire, 30 B.C.–476 A.D. 3. Rome—Politics and government—30 B.C.–476 A.D. I. Title. DG77.D86 2010 937Ј.06—dc22 2010016225 ⅜ϱ ீThe paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/ NISO Z39.48–1992. Printed in the United States of America ................ -

The Other Face of Augustus's Aggressive Inclination to Egypt

Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality Volume 12 - June 2015 - No 1 - Pages: (35 : 56) The Other Face of Augustus’s Aggressive Inclination to Egypt Wahid Omran Lecturer in Tourist Guidance Dep., Faculty of Tourism and Hotels, Fayoum University Introduction The initial attitude of Octavian against Egypt is proved by his speech to his troops on the evening before the battle of Actium. Pride in his Roman birth is compared to the despicability of an Egyptian woman as an opponent, who is supported by Dio Cassius reference.1 "Alexandrians and Egyptians- what worse or what truer name could one apply to them?- who worship reptiles and beasts as gods, who embalm their own bodies to give them semblance of immortality, who are most reckless in effrontery but most feeble in courage, and worst of all are slaves to a woman and not to a man". Since The Roman poet Virgile (70- 19 B.C), 2 the Romans opposed the animal – cult of the Egyptians, and considered these gods as monsters.3 The Egyptian character of the Augustus's opponents is related to the Augustan propaganda, represented the Augustus's war against Antony and Cleopatra not only a civil war between Rome and Egypt, but like a struggle between the West and the East. Whose Mark Antony was a traitor joined the powers of the East, whereas Octavian's victory in Actium was not only for himself, but basically for Rome and the Romans. This struggle was described in literature's documents as a civil strife or a foreign war.4 Augustus also knew he had a compensated war against Antony and Cleopatra as a republican magistrate crushing Oriental despotism.5 He is supported by the Roman society ethics and the star of the sacred Caesar, on the other hand, Antony, once a great Roman commander-in-chief, but now supported by a foreign army and followed by unnamed Egyptian spouse.6 The Romans considered the battle not only a military, but either a religious one between the Roman and the Egyptian Pantheons. -

Byzantium's Balkan Frontier

This page intentionally left blank Byzantium’s Balkan Frontier is the first narrative history in English of the northern Balkans in the tenth to twelfth centuries. Where pre- vious histories have been concerned principally with the medieval history of distinct and autonomous Balkan nations, this study regards Byzantine political authority as a unifying factor in the various lands which formed the empire’s frontier in the north and west. It takes as its central concern Byzantine relations with all Slavic and non-Slavic peoples – including the Serbs, Croats, Bulgarians and Hungarians – in and beyond the Balkan Peninsula, and explores in detail imperial responses, first to the migrations of nomadic peoples, and subsequently to the expansion of Latin Christendom. It also examines the changing conception of the frontier in Byzantine thought and literature through the middle Byzantine period. is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow, Keble College, Oxford BYZANTIUM’S BALKAN FRONTIER A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, – PAUL STEPHENSON British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow Keble College, Oxford The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011-4211, USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, VIC 3207, Australia Ruiz de Alarcón 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain Dock House, The Waterfront, Cape Town 8001, South Africa http://www.cambridge.org © Paul Stephenson 2004 First published in printed format 2000 ISBN 0-511-03402-4 eBook (Adobe Reader) ISBN 0-521-77017-3 hardback Contents List ofmaps and figurespagevi Prefacevii A note on citation and transliterationix List ofabbreviationsxi Introduction .Bulgaria and beyond:the Northern Balkans (c.–) .The Byzantine occupation ofBulgaria (–) .Northern nomads (–) .Southern Slavs (–) .The rise ofthe west,I:Normans and Crusaders (–) .