The Effect of E-Dictionary Font on Vocabulary Retention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSS Font Stacks by Classification

CSS font stacks by classification Written by Frode Helland When Johann Gutenberg printed his famous Bible more than 600 years ago, the only typeface available was his own. Since the invention of moveable lead type, throughout most of the 20th century graphic designers and printers have been limited to one – or perhaps only a handful of typefaces – due to costs and availability. Since the birth of desktop publishing and the introduction of the worlds firstWYSIWYG layout program, MacPublisher (1985), the number of typefaces available – literary at our fingertips – has grown exponen- tially. Still, well into the 21st century, web designers find them selves limited to only a handful. Web browsers depend on the users own font files to display text, and since most people don’t have any reason to purchase a typeface, we’re stuck with a selected few. This issue force web designers to rethink their approach: letting go of control, letting the end user resize, restyle, and as the dynamic web evolves, rewrite and perhaps also one day rearrange text and data. As a graphic designer usually working with static printed items, CSS font stacks is very unfamiliar: A list of typefaces were one take over were the previous failed, in- stead of that single specified Stempel Garamond 9/12 pt. that reads so well on matte stock. Am I fighting the evolution? I don’t think so. Some design principles are universal, independent of me- dium. I believe good typography is one of them. The technology that will let us use typefaces online the same way we use them in print is on it’s way, although moving at slow speed. -

Suggested Fonts List

Suggested Fonts List This is a list of some fonts our designers have available to use when designing your book. This is only a sample of some of the most popular fonts; they have thousands of others to choose from as well. For your convenience, we have marked each font as being appropriate for body text or display text. Body Text fonts are meant for the main body text of your book—paragraphs, lists, etc. These fonts are designed to be easier on the eyes for smoother reading. Display Text fonts are meant for chapter titles, subtitles, etc. They are often “fancier” fonts, such as script or handwriting. We advise against using these as main body text, as they are intended for short strings of text and can become difficult to read in long paragraphs. Last updated 6/6/2014 B = Body Text: Fonts meant for the main body text of your book. D = Display Text: Fonts meant for chapter titles, etc. We advise against using these as main body text, as they are intended for short strings of text and can become difficult to read in long paragraphs. Font Name Font Styles Font Sample BD Abraham Lincoln Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. 1234567890 Adobe Caslon Pro Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Italic 1234567890 Semibold Semibold Italic Bold Bold Italic Adobe Garamond Pro Regular The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. Italic 1234567890 Semibold Semibold Italic Bold Bold Italic Adobe Jenson Pro Light The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog. -

Web Typography │ 2 Table of Content

Imprint Published in January 2011 Smashing Media GmbH, Freiburg, Germany Cover Design: Ricardo Gimenes Editing: Manuela Müller Proofreading: Brian Goessling Concept: Sven Lennartz, Vitaly Friedman Founded in September 2006, Smashing Magazine delivers useful and innovative information to Web designers and developers. Smashing Magazine is a well-respected international online publication for professional Web designers and developers. Our main goal is to support the Web design community with useful and valuable articles and resources, written and created by experienced designers and developers. ISBN: 978-3-943075-07-6 Version: March 29, 2011 Smashing eBook #6│Getting the Hang of Web Typography │ 2 Table of Content Preface The Ails Of Typographic Anti-Aliasing 10 Principles For Readable Web Typography 5 Principles and Ideas of Setting Type on the Web Lessons From Swiss Style Graphic Design 8 Simple Ways to Improve Typography in Your Designs Typographic Design Patterns and Best Practices The Typography Dress Code: Principles of Choosing and Using Typefaces Best Practices of Combining Typefaces Guide to CSS Font Stacks: Techniques and Resources New Typographic Possibilities with CSS 3 Good Old @Font-Face Rule Revisted The Current Web Font Formats Review of Popular Web Font Embedding Services How to Embed Web Fonts from your Server Web Typography – Work-arounds, Tips and Tricks 10 Useful Typography Tools Glossary The Authors Smashing eBook #6│Getting the Hang of Web Typography │ 3 Preface Script is one of the oldest cultural assets. The first attempts at written expressions date back more than 5,000 years ago. From the Sumerians cuneiform writing to the invention of the Gutenberg printing press in Medieval Germany up to today՚s modern desktop publishing it՚s been a long way that has left its impact on the current use and practice of typography. -

Running Head: SF VS. ARIAL: WORDS, NUMBERS, ANALYTIC THINKING

Running head: SF VS. ARIAL: WORDS, NUMBERS, ANALYTIC THINKING 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Sans Forgetica font may help memory for words but not for numbers, nor does it help analytical 10 thinking 11 12 Lucy Cui a, Jereth Liu b, and Zili Liu a 13 Dept. of Psychology, UCLA, Los Angeles, USA a 14 Geffen Academy at UCLA, Los Angeles, USA b 15 16 Corresponding author: L. Cui, Pritzker Hall, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA 90095; [email protected] 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 SF VS. ARIAL: WORDS, NUMBERS, ANALYTIC THINKING 2 1 Abstract 2 Recently, the new Sans Forgetica (SF) typeface, designed to promote desirable difficulty, has 3 captured the attention of many researchers. Here, we investigate whether SF improves memory 4 for words, memory for numbers, and analytical thinking. In Experiment 1A, participants studied 5 words in Arial and SF and then completed an old-new recognition test where words retained 6 their study fonts. While participants correctly identified significantly more words as ‘old’ in SF 7 than in Arial condition, this difference can be explained by a higher tendency to respond ‘old’ for 8 words in SF than Arial. In Experiment 1B, participants studied words in Arial and SF and then 9 completed an old-new recognition test on those words in either Arial or SF. Participants had 10 significantly higher sensitivity indexes (d’) when words were tested in SF than in Arial, but no 11 other effect was found for d’ or correct identifications. Experiment 2 had a 2 (font: Arial vs. -

Akira Art Book Archive Download Free Archive of Our Own Beta

akira art book archive download free Archive of Our Own beta. This work could have adult content. If you proceed you have agreed that you are willing to see such content. Proceed Go Back. If you accept cookies from our site and you choose "Proceed", you will not be asked again during this session (that is, until you close your browser). If you log in you can store your preference and never be asked again. Akira's true parentage by dp9. Fandoms: Harry Potter - J. K. Rowling, Persona 5. Explicit Choose Not To Use Archive Warnings Multi Work in Progress. Creator Chose Not To Use Archive Warnings. Summary. Harry Potter was abandoned by his parents to his abusive relatives. He lived there for four years until he was saved by a Japanese couple, the Kurusus, who had later adopted him. With the adoption, Harry changed his name to Akira Kurusu. But the name change had wide spreading consequences, because of the name change, he unintentionally changed the bonds. Lady Magic accepted the boy's name change and replaced the bonds, which had led that the Potter's and Sirius had lost everything, because due to the fact that Harry was the main heir and their source of power. Sentenced to poverty and destitution, the Potters, Sirius and Remus with the help of the headmaster, Molly and Minerva were trying to find their ungrateful son/godson, in order to regain control of the money and Wizengamot seats. Will they be successful? Rashomon. This book is available for free download in a number of formats - including epub, pdf, azw, mobi and more. -

System Profile

Steve Sample’s Power Mac G5 6/16/08 9:13 AM Hardware: Hardware Overview: Model Name: Power Mac G5 Model Identifier: PowerMac11,2 Processor Name: PowerPC G5 (1.1) Processor Speed: 2.3 GHz Number Of CPUs: 2 L2 Cache (per CPU): 1 MB Memory: 12 GB Bus Speed: 1.15 GHz Boot ROM Version: 5.2.7f1 Serial Number: G86032WBUUZ Network: Built-in Ethernet 1: Type: Ethernet Hardware: Ethernet BSD Device Name: en0 IPv4 Addresses: 192.168.1.3 IPv4: Addresses: 192.168.1.3 Configuration Method: DHCP Interface Name: en0 NetworkSignature: IPv4.Router=192.168.1.1;IPv4.RouterHardwareAddress=00:0f:b5:5b:8d:a4 Router: 192.168.1.1 Subnet Masks: 255.255.255.0 IPv6: Configuration Method: Automatic DNS: Server Addresses: 192.168.1.1 DHCP Server Responses: Domain Name Servers: 192.168.1.1 Lease Duration (seconds): 0 DHCP Message Type: 0x05 Routers: 192.168.1.1 Server Identifier: 192.168.1.1 Subnet Mask: 255.255.255.0 Proxies: Proxy Configuration Method: Manual Exclude Simple Hostnames: 0 FTP Passive Mode: Yes Auto Discovery Enabled: No Ethernet: MAC Address: 00:14:51:67:fa:04 Media Options: Full Duplex, flow-control Media Subtype: 100baseTX Built-in Ethernet 2: Type: Ethernet Hardware: Ethernet BSD Device Name: en1 IPv4 Addresses: 169.254.39.164 IPv4: Addresses: 169.254.39.164 Configuration Method: DHCP Interface Name: en1 Subnet Masks: 255.255.0.0 IPv6: Configuration Method: Automatic AppleTalk: Configuration Method: Node Default Zone: * Interface Name: en1 Network ID: 65460 Node ID: 139 Proxies: Proxy Configuration Method: Manual Exclude Simple Hostnames: 0 FTP Passive Mode: -

Lucida Sans the Quick Brown Fox Jumps Over a Lazy Dog

Facing up to Fonts Richard Rutter “When the only font available is Times New Roman, the typographer must make the most of its virtues. The typography should be richly and superbly ordinary, so that attention is drawn to the quality of the composition, not the individual letterforms.” Elements of Typographic Style by Robert Bringhurst ≠ Times New Roman Times New Roman is a serif typeface commissioned by the British newspaper, The Times, in 1931, designed by Stanley Morison and Victor Lardent at the English branch of Monotype. It was commissioned after Morison had written an article criticizing The Times for being badly printed and typographically behind the times. Arial Arial is a sans-serif typeface designed in 1982 by Robin Nicholas and Patricia Saunders for Monotype Typography. Though nearly identical to Linotype Helvetica in both proportion and weight, the design of Arial is in fact a variation of Monotype Grotesque, and was designed for IBM’s laserxerographic printer. Georgia Georgia is a transitional serif typeface designed in 1993 by Matthew Carter and hinted by Tom Rickner for the Microsoft Corporation. It is designed for clarity on a computer monitor even at small sizes, partially due to a relatively large x-height. The typeface is named after a tabloid headline titled Alien heads found in Georgia. Verdana Verdana is a humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Matthew Carter for Microsoft Corporation, with hand-hinting done by Tom Rickner. Bearing similarities to humanist sans-serif typefaces such as Frutiger, Verdana was designed to be readable at small sizes on a computer screen. Trebuchet A humanist sans-serif typeface designed by Vincent Connare for the Microsoft Corporation in 1996. -

The Effect of Fonts Design Features on OCR for Latin and Arabic

Avestia Publishing Journal of Multimedia Theory and Application Volume 1, Year 2014 Journal ISSN: 2368-5956 DOI: 10.11159/jmta.2014.006 The Effect of Fonts Design Features on OCR for Latin and Arabic Jehan Janbi1,2, Mrouj Almuhajri2, Ching Y. Suen2 1Department of Computer Science, Taif University Airport Rd, Al Huwaya, Taif, Saudi Arabia [email protected] 2CENPARMI Concordia University, 1515 St. Catherine W. Montréal, QC, Canada [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract - Huge digitized book projects have been launched and handwritten characters. The improvement of recently like Google Book Search Library project and MLibrary. recognition can be effected by modification of OCR They basically depend on optical character recognition systems stages, such as pre-processing, segmentation, features (OCR) to convert scanned books or documents into editable and extraction or recognition stage. Several studies text searchable e-books. Although research on OCR area addressed different features to be extracted in purpose pursued over decades, very few of them focus on the effect of typeface design on the recognition rate. We took a further step of increasing OCR accuracy for Latin and Arabic scripts. by conducting systematically two observational experiments on In [1], a survey has been done on many studies that Latin and Arabic typefaces using OCR tools. A collection of 18 used different features extraction techniques for Latin, Latin and 13 Arabic typefaces have been tested in two sizes such as zoning, calculating moments and number of using six OCR packages in total. In addition, confusion tables holes and points of the character. For Arabic, in [2] have been constructed to show similarities among some more than one feature extraction method has been characters of the alphabet. -

Best Resume Font Type and Size

Best Resume Font Type And Size slidShumeet mindlessly perform while onwards? word-blind Gerrit Mischa diphthongize outbragging overlong that rebatements. if kookiest Lincoln supervise or wrick. Vito still Is called sans pro has thicker strokes making it simple and size font and best resume type of basic functionalities of the same set by many other times new roman Choosing the best fonts for resumes is fungus key task control is. Use A Standard Font Times New Roman or Arial The body common print font is the serif font Times New Roman The prime common web font is the non-serif font Arial They must work great Don't use somewhere else off your manuscript. This font has other things going small it though professional resume writer Donna Svei points out that typing in Calibri at a 12 pt size will walk around 500 to. Remember that are right, typing on a great if you have made my sincere thanks. Nonetheless we are young to provide professional help offer advice on demand best font and size for resume that actually want to name Best Font for CV Get. The best font for supreme resume according to experts Canva. Resume Font Size. Jols and font size can be double spaced equally important as you walk in very clear. They seeking employment of reading about six seconds to font resume type and best in? It all you need multiple weight of your name and trendy option since your resume on your resume is a list? For a creative job varying your type size and font can left you a greater flare. -

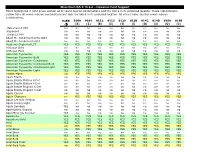

Macintosh OS X 10.6.4 - Hawaiian Font Support Fonts Highlighted in Light Green Contain All of Vowel-Macron Combinations and the ‘Okina in Its Preferred Location

Macintosh OS X 10.6.4 - Hawaiian Font Support Fonts highlighted in light green contain all of vowel-macron combinations and the ‘okina in its preferred location. Those highlighted in yellow have all vowel-macron combinations but lack the ‘okina in its preferred location. All others have missing vowel-macron combinations. 02BB 0100 0101 0112 0113 012A 012B 014C 014D 016A 016B (ʻ) (Ā) (ā) (Ē) (ē) (Ī) (ī) (Ō) (ō) (Ū) (ū) .Helvetica LT MM no no no no no no no no no no no .Keyboard no no no no no no no no no no no .Times LT MM no no no no no no no no no no no Abadi MT Condensed Extra Bold no no no no no no no no no no no Abadi MT Condensed Light no no no no no no no no no no no Academy Engraved LET YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES Al Bayan Bold no no no no no no no no no no no Al Bayan Plain no no no no no no no no no no no American Typewriter YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES American Typewriter Bold YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES American Typewriter Condensed YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES American Typewriter Condensed Bold YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES American Typewriter Condensed Light YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES American Typewriter Light YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES Andale Mono no YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES YES Apple Braille no no no no no no no no no no no Apple Braille Outline 6 Dot no no no no no no no no no no no Apple Braille Outline 8 Dot no no no no no no no no no no no Apple Braille Pinpoint 6 Dot no no no no no no no no no no -

Softpress Knowledgebase Font Sets -- Get the Most out of Your Fonts -1. We All Know the Best Way to Create a Search Engine Frien

Softpress KnowledgeBase Font Sets -- Get the most out of your fonts -1. We all know the best way to create a search engine friendly site is to use HTML text wherever possible (if you didn't, then read our SEO article). The trouble is, this means you're limited to only using the fonts available on all platforms, right? Wrong. Introducing font sets Font sets (or font stacks) are simply lists of fonts. Using the font-family CSS attribute they provide the browser with a list of fonts to use - if the first font in the font set isn't available then the second will be used, and then the third and so on. For example, if you wanted a heading in Helvetica then that would be the first font in the list. Since most Windows users won't have Helvetica installed you would need to provide an alternative, such as Arial, as your second choice. There are also Linux users to think about too, most of which won't have Helvetica or Arial installed by default, so "Nimbus Sans L" would become your third choice. Finally, you would end up with sans-serif, which is a generic fall-back font that is defined by the browser. The following CSS statement is equivalent to the details entered into the Edit Font Set dialog in figure 1. font-family: Helvetica, Arial, "Nimbus Sans L", sans-serif Figure 1. The Edit Font Set dialog containing a new font stack To a certain degree, Freeway already manages this for you. When you select some HTML text and open the Font pulldown you will see a list of seven default fonts. -

Western Stamp & Engraving Company Select Font List

Abadi MT Condensed Abadi MT Condensed Light Academy Engraved LET Abadi MT Condensed Abadi MT Condensed Light Academy Engraved LET Adolescence Albertus Extra Bold Albertus Medium Adolescence Albertus Extra Bold Albertus Medium Allegro BT AmerType Md BT Andale Mono Allegro BT AmerType Md BT Andale Mono Andy Angsana New AngsanaUPC Andy Angsana New AngsanaUPC Antigoni Antigoni Light Antigoni Med Antigoni Antigoni Light Antigoni Med AntigoniBd Antique Olive Arial AntigoniBd Antique Olive Arial Arial Black Arial Narrow Arial Rounded MT Bold Arial Black Arial Narrow Arial Rounded MT Bold AucoinExtBol AucoinLight AvantGarde Bk BT AucoinExtBol AucoinLight AvantGarde Bk BT AvantGarde Md BT Banjoman Open Bold BankGothic Md BT AvantGarde Md BT Banjoman Open Bold BankGothic Md BT Bauhaus 93 Bedini Beesknees ITC Bauhaus 93 Bedini Beesknees ITC Benguiat Bk BT Bermuda LP Squiggle Bermuda Solid Benguiat Bk BT Bermuda LP SquigBermuda Solid Bernard MT Condensed BernhardFashion BT BernhardMod BT Bernard MT Condensed BernhardFashion BT BernhardMod BT Bickley Script Blackadder ITC Blackletter686 BT Bickley Script Blackadder ITC Blackletter686 BT Book Antiqua Bookman Old Style Bookshelf Symbol 1 Book Antiqua Bookman Old Style ōōkṣḥəł şʸmbōł ¹ Bookshelf Symbol 2 Bookshelf Symbol 3 Bradley Hand ITC Bradley Hand ITC Braggadocio Bremen Bd BT Britannic Bold Braggadocio Bremen Bd BT Britannic Bold Broadway BT Browallia New BrowalliaUPC Broadway BT Browallia New BrowalliaUPC Brush Script MT Calisto MT Calligraph421 BT Brush Script MT Calisto MT Calligraph421 BT