ALEXA OWEN Spring 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Senior Scholar Papers Student Research 1998 From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition Rebecca Troeger Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Troeger, Rebecca, "From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition" (1998). Senior Scholar Papers. Paper 548. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/548 This Senior Scholars Paper (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Scholar Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Rebecca Troeger From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition • The Irish literary tradition has always been inextricably bound with the idea of image-making. Because of ueland's historical status as a colony, and of Irish people's status as dispossessed of their land, it has been a crucial necessity for Irish writers to establish a sense of unique national identity. Since the nationalist movement that lead to the formation of the Insh Free State in 1922 and the concurrent Celtic Literary Re\'ivaJ, in which writers like Yeats, O'Casey, and Synge shaped a nationalist consciousness based upon a mythology that was drawn only partially from actual historical documents, the image of Nation a. -

Winter 2019 Vol. 45, No. 1

The American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing Extraordinary Flies Fly tier Ryan Whitney brought flies to Hooked on the Holidays that kids could drop into their hand-decorated ornaments. He and Bill Sylvester were on hand to tie flies, and Yoshi Foster Bam Robert A. Oden Jr. Akiyama helped the youngest Dave Beveridge Erik R. Oken participants tie clown flies. Other Peter Bowden Annie Hollis Perkins holiday activities included a trout- Mark Comora Leigh H. Perkins Kelsey McBride Kelsey cookie decorating station. Deborah Pratt Dawson Frederick S. Polhemus Ronald Gard Roger Riccardi , D D of Branford, of his passing, immediately began com- Alan Gnann Robert G. Scott Connecticut, donated a collection of forting one another with stories. Former Gardner Grant Jr. Nicholas F. Selch Iflies to the museum. When museum Hexagraph owner Harry Briscoe and I John Hadden Ronald B. Stuckey staff were gathering artifacts for an exhibit exchanged several e-mails. In one, he men- James Heckman, MD Tyler S. Thompson in , they rediscovered the flies, which tioned the hand-created Christmas greet- Karen Kaplan Richard G. Tisch turned out to be, as far as anyone knows, ings that John used to send. “Each was an Woods King III David H. Walsh the oldest in existence. The Harris collec- original in its own right, signed and some- William P. Leary III Andrew Ward tion—so named for author John Richard times numbered . the opposing side con- Anthony J. Magardino Patricia Watson Harris, an Irish entomologist who owned tained a handwritten note—always in pen- the collection at a key point in its long his- cil. -

Eavan Boland's Poetic Sequences

Colby Quarterly Volume 35 Issue 4 December Article 5 December 1999 "A Deliberate Collection of Cross Purposes": Eavan Boland's Poetic Sequences Michael Thurston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 35, no.4, December 1999, p.229-251 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Thurston: "A Deliberate Collection of Cross Purposes": Eavan Boland's Poeti 1/A Deliberate Collection of Cross Purposes": Eavan Boland's Poetic Sequences by MICHAEL THURSTON EGINNING IN THE EARLY 1980s, Eavan Boland began to work not only in Bindividual lyrics but in slightly longer poems ("The Journey") and sequences of lyrics (including the poems gathered in In Her Own Image). Indeed, since the 1990 American appearance of Outside History: Selected Poems 1980-1990, each of Boland's books has included at least one such sequence (Outside History included two, the title sequence and also "Domestic Interior," which consisted of poems originally published as free standing lyrics, first gathered into a titled sequence in this American publica tion). While they share the central concerns that have structured Boland's career, each sequence focuses its meditation through a different thematic lens. "Domestic Interior" elaborates and problematizes its titular familial spaces as a haven from history; "Outside History" develops, questions, and finally rejects the possibility of finding and inhabiting any space "outside his tory" and explores the kinds of spaces available within the history the poet ultimately chooses; "Writing in a Time of Violence" takes up language itself and the role of representation in the construction of history and the subject's response to it; and "Colony," from Boland's most recent collection, The Lost Land, meditates on such public repositories of historic residues as cityscapes and monuments. -

SA Police Gazette 1946

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently The resolution of this sampler has been reduced from the original on CD to keep the file smaller for download. South Australian Police Gazette 1946 Ref. AU5103-1946 ISBN: 978 1 921494 85 7 This book was kindly loaned to Archive CD Books Australia by the South Australia Police Historical Society www.sapolicehistory.org Navigating this CD To view the contents of this CD use the bookmarks and Adobe Reader’s forward and back buttons to browse through the pages. -

YAMU.LK PP- YAMU Range Ad Oct 15 FINAL.Pdf 1 10/15/15 2:55 PM

FREE The Sushi Bento at Naniyori MARCH/2016 WWW.YAMU.LK PP- YAMU Range Ad Oct 15 FINAL.pdf 1 10/15/15 2:55 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K PP- YAMU Range Ad Oct 15 FINAL.pdf 1 10/15/15 2:55 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 4 [insert title here] - this is the actual title We’ve got some great stuff in this issue. We did our first EDITORIAL ever quiz, where you can gauge your competency as a Indi Samarajiva Colombar. If you feel inadequate after that, we’ve hooked Bhagya Goonewardhane you up with a guide to 24 hours in Colombo to impress Aisha Nazim Imaad Majeed your visiting friends! Shifani Reffai Kinita Shenoy We’ve also done lots of chill travels around the island, from Batti to Koggala Lake to Little Adam’s Peak. There’s ADVERTISING going to be plenty more coming up as we go exploring Dinesh Hirdaramani during the April holidays, so check the site yamu.lk for 779 776 445 / [email protected] more. CONTACT 11 454 4230 (9 AM - 5 PM) With the Ides of March around the corner, just remember [email protected] that any salad is a Caesar Salad if you stab it enough. PRINTED BY Imashi Printers ©2015 YAMU (Pvt) Ltd 14/15A Duplication Road, Col 4 kinita KIITO WE DO SUITS Damith E. Cooray CText ATI Head Cutter BSc (Hons) International Clothing Technology & Design Manchester Metropolitan University, UK Sole Distributor of Flagship Store KIITO Bespoke & Workshop # 19 , First Floor, Auditor General’s Department Building # 27, Rosmead Place Arcade Independance Square Colombo 07 Colombo 07 0112 690740 0112 675670 8 SCARLET ROOM 32, Alfred House Avenue, Colombo 03 | 11 4645333 BY BHAGYA their dishes with the exception Risotto Paella (Rs. -

Papers of HC Gregory

2001/ 108 Personal and family papers of H. C. Gregory Private Sources at the National Archives H.C. Gregory 2001/108 1 2001/ 108 Personal and family papers of H. C. Gregory ACCESSION NO. 2001/108 DESCRIPTION Personal and family papers of H. C. Gregory, Callan, Co. Kilkenny. Solicitor and Land Commissioner c.1792–c. 1973 DATE OF ACCESSION 28 November 2001 ACCESS Open 2 2001/ 108 Personal and family papers of H. C. Gregory 1. General Correspondence of H. C. Gregory 1870–1909 2. Correspondence of H. C. Gregory relating to Stevenson Estate 1840–1888 3. Correspondence of Mrs. A. F. Gregory 1884–1924 4. Correspondence of The Rev. William Gregory 1856–1868 5. General Correspondence 1862–1973 6. Documents of Charles Stewart Miller, Brother-in-law of H.C.G. 1835–1850 7. Deeds 1810–1910 8. Irish Land Commission 1881–1896 9. Rentals 1792–1919 10. Financial 1864–1918 11. Testamentary 1853–1965 12. Genealogy 1896–1952 13. Newspaper Cuttings 1887–1890 14. Miscellaneous 1868–1915 3 2001/ 108 Personal and family papers of H. C. Gregory Biographical History Henry Charles Gregory was born in West Court, Callan, Co. Kilkenny on the 10 August 1827. He was the son of the Reverend William Gregory (1792– 1874), the Rector of Fiddown, Co. Kilkenny. H. C. Gregory’s great grandfather, Robert Gregory, was chairman of the Old East India Company during the stormy times of Clive and Warren Hastings, and subsequently was MP for Rochester for many years. His grandfather, William Gregory, was Under Secretary for Ireland from 1813 to 1831, during which time he was twice offered a Baronetcy, which he refused, and so on his retirement he was made a Privy Councillor. -

ENP11011 Eavan Boland and Modern Irish Poetry

ENP11011 Eavan Boland and Modern Irish Poetry Module type Optional (approved module: MPhil in Irish Writing) Term / hours Hilary / 22 ECTS 10 Coordinator(s) Dr Rosie Lavan ([email protected]) Dr Tom Walker ([email protected]) Lecturer(s) Dr Rosie Lavan Dr Tom Walker Cap Depending on demand Module description Eavan Boland is one of the most significant Irish poets of the past century. In a career of more than 50 years, she persistently questioned, and radically expanded, the parameters of Irish poetry and the definition of the Irish poet. The course will examine a wide range of Eavan Boland’s poetry and prose. Seminars are structured around some of the poet’s major themes and modes. These will also be interspersed with seminars that seek to place Boland within the broader history of modern Irish poetry, via comparisons with the work and careers of Blanaid Salkeld, Patrick Kavanagh, Derek Mahon, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin and Paula Meehan. Also explored will be relevant historical and cultural contexts, and questions of poetics and ideology. Assessment The module is assessed through a 4,000-word essay. Indicative bibliography Students will need to purchase a copy of Eavan Boland, New Selected Poems (Carcanet/Norton) and Eavan Boland, Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Time (Carcanet/Vintage/Norton) as the core course texts. Please note: it is expected that students will read Object Lessons in full before the start of the course. All other primary material needed through the term will be made available via Blackboard. This will include poems from Boland’s collections published since the appearance of New Collected Poems (Domestic Violence, A Woman Without A Country and The Historians) and the work of the other poets to be studied on the course, as well as various other relevant essays, articles and interviews. -

Mohamed Salah Harzallah the Great Irish Famine Is a Watershed Event In

Brolly. Journal of Social Sciences 3 (3) 2020 SITES OF CINEMATOGRAPHIC MEMORY: “BLACK’47” AS A CONSTRUCTION OF THE IRISH PAST Mohamed Salah Harzallah Associate Professor of Irish and British Studies, University of Sousse, Tunisia [email protected] Abstract. This article deals with how the history of the Great Irish Famine of the 1840s is reconstructed and presented to the global viewers of the film Black’47 (2018). It shows that the film’s narrative reflected a Nationalist perception of the Irish past which condemns the role of the British politicians of the time. It also concludes that the film provides an opportunity for the Irish in Ireland and abroad with a site of cinematographic memory that transcends the national borders of Ireland and engages the public in the process of remembering and reconstructing the history of this calamity. Keywords: Irish film, Great Irish Famine, memory, public history, Black 47, Irish history The Great Irish Famine is a watershed event in Ireland, the memory of which has survived in the Irish collective memory until the present day. In the last two decades, a plethora of publications dealt with the Famine events from different perspectives while dividing scholars into three major groups. Nationalist, Revisionist and Post- Revisionist historians provided divergent views about what happened in Ireland in the 1840s. Apart from professional historians, the filmmaker Lance Daly contributed to the construction of the Famine events in his film Black’47 (2018). He attempted to show how the Irish lived under British rule in the year 1847 - the peak of Famine. Traditional historians, who show commitment to method and training, have shown a rejection of films as a source of information 73 Mohamed Salah Harzallah – Sites of Cinematographic Memory as filmmakers often sacrifice truth to an emotional and subjective construction of the events. -

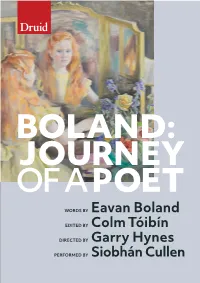

Boland Journey of a Poet Show Programme

BACK TO CONTENTS BOLAND: JOURNEY OF A POET WORDS BY Eavan Boland EDITED BY Colm Tóibín DIRECTED BY Garry Hynes PERFORMED BY Siobhán Cullen 1 BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS Contents Cast and Creatives 5 Finding a voice ... 6 When Silence Is Broken 8 Eavan Boland 12 Production Team 14 Thank You 15 Biographies 17 Druid Staff 28 Druid Supporters 29 Druid Friends 30 Become a Friend 31 Rehearsal Photograph: Emilija Jefremova 2 3 BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS CAST AND CREATIVES BOLAND: JOURNEY OF A POET A Druid at Home production LIVE STREAM PERFORMANCES 22 – 24 APRIL 2021 AVAILABLE ON DEMAND 27 APRIL – 2 MAY 2021 WORDS BY Eavan Boland EDITED BY Colm Tóibín DIRECTED BY Garry Hynes PERFORMED BY Siobhán Cullen DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY Colm Hogan SET DESIGNER Francis O’Connor COSTUME DESIGNER Clíodhna Hallissey SOUND DESIGNER Sinéad Diskin COMPOSER Conor Linehan PORTRAIT ARTIST Debbie Chapman DURATION 60 minutes approximately with no interval JOIN THE CONVERSATION @DruidTheatre #BolandJourneyOfAPoet #DruidAtHome Rehearsal Photograph: Emilija Jefremova 4 5 BACK TO CONTENTS PROGRAMME NOTE PROGRAMME NOTE Much later, when I was preparing my Inaugural Address as ‘Finding a voice where President, I told Eavan I wanted to refer to women who had been outside history – a phrase we had both discussed together. She they found a vision’ gave me the lovely last line, from ‘The Singers’, which she was still working on: ‘Finding a voice where they found a vision’. I am delighted that Druid is presenting Boland: Journey of a Poet. Eavan had a great gift for friendship and I was lucky I visited Eavan several times in Stanford and came to know how enough to become a close friend when we were students loved and respected she was there. -

Beleaguered Spaces in Eavan Boland's Domestic Violence

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 18 | 2019 Guerre en poésie, poésie en guerre “This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence Bertrand Rouby Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/16298 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.16298 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Bertrand Rouby, ““This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence”, Miranda [Online], 18 | 2019, Online since 15 April 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/16298 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.16298 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. “This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence 1 “This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence Bertrand Rouby 1 Since the 1960s, many are the poets who have tackled the period known as The Troubles, though few with as much emphasis on domesticity as Eavan Boland. Together with Seamus Heaney, Derek Mahon and Michael Longley, she is one of a handful of Irish writers who have managed to address the issue of domestic conflicts with an equally concise and vivid style of writing, using tropes related to personal and shared experience1. Drawing on metaphors and metonymies from everyday life and her immediate surroundings, Boland eschews the pitfalls of oblique or circuitous writing, even though her use of personal imagery makes for an indirect approach. -

Defending Ireland Or Attacking Woman? the Irish Riposte to Harriet Martineau

Defending Ireland or Attacking Woman? The Irish Riposte to Harriet Martineau Julie Donovan owhere is the complexity of Harriet Martineau’s legacy more N evident than in her writings on Ireland. Martineau traveled to Ireland in 1831, a visit she followed up with a more extensive stay in 1852, when, with her customary zeal, she covered twelve-hundred miles, taking in all four provinces (Conway and Hill 47). Martineau’s first visit inspired “Ireland: A Tale” (1832), the ninth story in Illustrations of Political Economy (1832-34). Her second visit was instigated by Frederick Knight Hunt, editor of London’s Daily News, who requested eye-witness reports of Ireland’s post-famine socio-cultural recovery and economic progress, which Martineau would collate in her role as a traveling correspondent. Her findings from the 1852 visit were published in voluminous journalism, including Letters from Ireland (1852) and Endowed Schools of Ireland (1859), which formed part of her reporting for Daily News. In addition, numerous and formerly scattered pieces on Ireland, published in Daily News, Household Words, Westminster Review and elsewhere, have been collected in Harriet Martineau and the Irish Question: Condition of Post- Famine Ireland, edited by Deborah Logan. Irish affairs permeated Martineau’s fiction and non-fiction, demonstrating how cognizant she was of issues Ireland faced in the post- famine context and in terms of continuing systemic problems impeding recovery, such as absentee landlordism, which she had raised in “Ireland: A Tale.” Throughout her decades of writing about Ireland, from pre- to post- 117 Nineteenth-Century Prose, Vol. 47, No. -

The Descendants of John Pease 1

The Descendants of John Pease 1 John Pease John married someone. He had three children: Edward, Richard and John. Edward Pease, son of John Pease, was born in 1515. Basic notes: He lived at Great Stambridge, Essex. From the records of Great Stambridge. 1494/5 Essex Record office, Biography Pease. The Pease Family, Essex, York, Durham, 10 Henry VII - 35 Victoria. 1872. Joseph Forbe and Charles Pease. John Pease. Defendant in a plea touching lands in the County of Essex 10 Henry VII, 1494/5. Issue:- Edward Pease of Fishlake, Yorkshire. Richard Pease of Mash, Stanbridge Essex. John Pease married Juliana, seized of divers lands etc. Essex. Temp Henry VIII & Elizabeth. He lived at Fishlake, Yorkshire. Edward married someone. He had six children: William, Thomas, Richard, Robert, George and Arthur. William Pease was born in 1530 in Fishlake, Yorkshire and died on 10 Mar 1597 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. William married Margaret in 1561. Margaret was buried on 25 Oct 1565 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. They had two children: Sibilla and William. Sibilla Pease was born on 4 Sep 1562 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. Basic notes: She was baptised on 12 Oct 1562. Sibilla married Edward Eccles. William Pease was buried on 25 Apr 1586. Basic notes: He was baptised on 29 May 1565. William next married Alicia Clyff on 25 Nov 1565 in Fishlake, Yorkshire. Alicia was buried on 19 May 1601. They had one daughter: Maria. Maria Pease Thomas Pease Richard Pease Richard married Elizabeth Pearson. Robert Pease George Pease George married Susanna ?. They had six children: Robert, Nicholas, Elizabeth, Alicia, Francis and Thomas.