Other Irelands in Contemporary Women's Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Senior Scholar Papers Student Research 1998 From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition Rebecca Troeger Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Troeger, Rebecca, "From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition" (1998). Senior Scholar Papers. Paper 548. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/548 This Senior Scholars Paper (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Scholar Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Rebecca Troeger From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition • The Irish literary tradition has always been inextricably bound with the idea of image-making. Because of ueland's historical status as a colony, and of Irish people's status as dispossessed of their land, it has been a crucial necessity for Irish writers to establish a sense of unique national identity. Since the nationalist movement that lead to the formation of the Insh Free State in 1922 and the concurrent Celtic Literary Re\'ivaJ, in which writers like Yeats, O'Casey, and Synge shaped a nationalist consciousness based upon a mythology that was drawn only partially from actual historical documents, the image of Nation a. -

Women Writers of the Troubles

Women Writers of The Troubles Britta Olinder, University of Gothenburg Abstract During the thirty years of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, writing by women was difficult to find, especially concerning the conflict and its violence. The publication of the first three heavy volumes of The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing towards the end of that period demonstrated the blindness of its male editors to female writing, leading to another two volumes focusing on women and also presenting more than expected on the conflict itself. Through looking at a selection of prose, poretry and drama written by women, this article wishes to illuminate a number of relevant issues such as: How have female writers reacted to the hate and violence, the social and political insecurity in their writing of poetry, plays and fiction? Is Robert Graecen’s question ‘Does violence stimulate creativity?’—in a letter to the Irish Times (18 Jun. 1974)—relevant also for women? In this very partial exploration, I have chosen to discuss a novel by Jennifer Johnston (Shadows on Our Skin, 1977) and one by Deirdre Madden (One by One in the Darkness, 1996), a well-known short story by Mary Beckett (‘A Belfast Woman,’ 1980), together with plays by Anne Devlin (Ourselves Alone, 1986) and Christina Reid (Tea in a China Cup, 1987), as well as poetry, by, among others, Meta Mayne Reid, Eleanor Murray, Fleur Adcock and Sinéad Morrissey. Keywords: women writers; violence; conflict; The Troubles; Jennifer Johnston; Deirdre Madden; Mary Beckett; Anne Devlin; Christina Reid; Meta Mayne Reid; Eleanor Murray; Fleur Adcock; Sinéad Morrissey The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere The ceremony of innocence is drowned; The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. -

Get PDF ~ Something Beginning with P: New Poems from Irish Poets

UW8YGV4IJMBX » eBook » Something Beginning with P: New Poems from Irish Poets Read PDF SOMETHING BEGINNING WITH P: NEW POEMS FROM IRISH POETS O Brien Press Ltd, Ireland, 2008. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Corrina Askin, Alan Clarke (illustrator). 3rd Revised edition. 231 x 193 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. A beautiful collection of specially-commissioned new poems for children of all ages. Includes poems from leading Irish poets: Seamus Heaney, Thomas Kinsella, Maighread Medbh * Paula Meehan * Brendan Kennelly * Michael Longley * Rita Ann Higgins * Matthew Sweeney * Biddy Jenkinson * Desmond O Grady * Richard Murphy * Nuala... Read PDF Something Beginning with P: New Poems from Irish Poets Authored by Seamus Cashman Released at 2008 Filesize: 1.6 MB Reviews This ebook is definitely not effortless to get going on looking at but quite entertaining to read. It really is rally exciting throgh reading period. Its been developed in an exceptionally easy way and is particularly simply following i finished reading through this ebook through which basically changed me, alter the way i believe. -- Piper Gleason DDS Without doubt, this is actually the best function by any article writer. It is probably the most amazing ebook i have got go through. Your lifestyle period will likely be enhance once you complete reading this article publication. -- Brody Parisian TERMS | DMCA IYI57TVCBOTI » Kindle » Something Beginning with P: New Poems from Irish Poets Related Books Any Child Can Write Who am I in the Lives of Children? An Introduction to Early Childhood Education The Well-Trained Mind: A Guide to Classical Education at Home (Hardback) The First Epistle of H. -

Female Ulster Poets and Sexual Politics

Colby Quarterly Volume 27 Issue 1 March Article 3 March 1991 "Our Lady, dispossessed": Female Ulster Poets and Sexual Politics Jacqueline McCurry Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 27, no.1, March 1991, p.4-8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. McCurry: "Our Lady, dispossessed": Female Ulster Poets and Sexual Politics "Our1/Our Lady, dispossessed": Female Ulster Poets and Sexual Politics by JACQUELINE MCCURRY OETRY AND POLITICS, like church and state, should be separated," writes P Belfast critic Edna Longley (185); in Eire and in Northern Ireland this is not the case: the marriage of church and state in the Republic has resulted in constitutional bans on divorce and on abortion; Northern Ireland's Scots Presbyterian majority continues to preventminority Irish-Catholic citizens from having full participationin society. Butwhile mencontinue to control church and state, women have begun to raise their voices in poetry and in protest. Northern Ireland's new poets, through the 1960s and 1970s, were exclusively male: Jan1es Simmons, Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley, Derek Mahon, Paul Muldoon, Seamus Deane, Frank Ormsby, Tom Paulin, and Ciaran Carson dominated the literary scene until the early 1980s. In 1982 Medbh McGuckian published her first book ofpoetry. Since then, she has published two additional collections and achieved international fame, while younger women poets like Janet Shepperson and Ruth Hooley have made their debuts in print. -

Eavan Boland's Poetic Sequences

Colby Quarterly Volume 35 Issue 4 December Article 5 December 1999 "A Deliberate Collection of Cross Purposes": Eavan Boland's Poetic Sequences Michael Thurston Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 35, no.4, December 1999, p.229-251 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Thurston: "A Deliberate Collection of Cross Purposes": Eavan Boland's Poeti 1/A Deliberate Collection of Cross Purposes": Eavan Boland's Poetic Sequences by MICHAEL THURSTON EGINNING IN THE EARLY 1980s, Eavan Boland began to work not only in Bindividual lyrics but in slightly longer poems ("The Journey") and sequences of lyrics (including the poems gathered in In Her Own Image). Indeed, since the 1990 American appearance of Outside History: Selected Poems 1980-1990, each of Boland's books has included at least one such sequence (Outside History included two, the title sequence and also "Domestic Interior," which consisted of poems originally published as free standing lyrics, first gathered into a titled sequence in this American publica tion). While they share the central concerns that have structured Boland's career, each sequence focuses its meditation through a different thematic lens. "Domestic Interior" elaborates and problematizes its titular familial spaces as a haven from history; "Outside History" develops, questions, and finally rejects the possibility of finding and inhabiting any space "outside his tory" and explores the kinds of spaces available within the history the poet ultimately chooses; "Writing in a Time of Violence" takes up language itself and the role of representation in the construction of history and the subject's response to it; and "Colony," from Boland's most recent collection, The Lost Land, meditates on such public repositories of historic residues as cityscapes and monuments. -

"An Island Once Again: the Postcolonial Aesthetics of Contemporary Irish Poetry"

Colby Quarterly Volume 37 Issue 2 June Article 8 June 2001 "An Island Once Again: The Postcolonial Aesthetics of Contemporary Irish Poetry" Jefferson Holdridge Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 37, no.2, June 2001, p.189-200 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Holdridge: "An Island Once Again: The Postcolonial Aesthetics of Contemporar IIAn Island Once Again: The Postcolonial Aesthetics of Contemporary Irish Poetry" By JEFFERSON HOLDRIDGE World is the ever nonobjective to which we are subject as long as the paths of birth and death, blessing and curse keep us transported into Being. Martin Heidegger, The Origin ofthe Work ofArt Flames have only lungs. Water is all eyes. The earth has bone for muscle.... But anxiety can find no metaphor to end it. A.K. Ramanujan, "Anxiety" HE POSITION OF THE SUBJECT, of history and landscape are the central Tthemes of any essay on the aesthetics of contemporary Irish poetry and often provoke as many questions as answers. To give specific weight to some broad theoretical analysis, this essay shall closely examine a selection of works. Before detailed discussion of the texts, the idea of a postcolonial aes thetic should be defined. The two important frames are provided first by a correlation between Fanon and Kant and second by various ideas of the psy choanalytical sublime. Politically, there are three Fanonite/Kantian stages to what is here termed the postcolonial sublime; it is an aesthetic that aligns Fanon's dialectic of decolonization, from occupation, through nationalism, to liberation with Kant's three stages of sublimity, that is, from balance between subject and object, through aesthetic violence upon the internal sense, to tran scendent compensation. -

A Few Contemporary Irish and Portuguese Women Poets

Contemporary Irish Poetry Profa.Gisele Wolkoff Universidade Federal Fluminense • (some) Contemporary Women Poets: Eavan Boland, Celia de Fréine, Kerry Hardie, Medbh McGuckian, Sinéad Morrissey, Vona Groarke, Rita Kelly, Rita Ann Higgins... groundbreaking publication THE FIELD DAY ANTHOLOGY OF IRISH WRITING – 1991, 1996 A Reading of Irish Poetry includes considerations upon: - religion;linguistic belonging. - politics;These elements allude us to - geographicthe spaces; issue of - linguisticthe private belonging. & the public, the Theselocale elements and the allude cosmopolitan. us to the issue of the private & the public, the locale and the cosmopolitan. “poetry begins where those isms stop” (Patricia Boyle Haberstroh, 1996:.11) politics begins when poetry continues Patricia Keely-Murphy´s The Greek Mystress & Judy Shinnick´s Nude II Eavan Boland and Tradition “I felt increasingly the distance between my own life, my lived experience and conventional interpretations of both poetry and the poet´s life. It was not exactly or even chiefly that the recurrences of my world – a child´s face, the dial of a washing machine – were absent from the tradition, although they were. It was not even so much that I was a woman. It was that being a woman, I had entered into a life for which poetry has no name.” (In: Object Lessons The Life of the Woman and The Poet In Our Time. 1995: 18) What is poetry/writing? the country of the mind (Seamus Heaney) “It is this feeling, assenting, equable marriage between the geographical country and the country of the mind (...) it is this marriage that constitutes the sense of place in its richest possible manifestation.” - the rhetoric of imagery (Eavan Boland).. -

ENP11011 Eavan Boland and Modern Irish Poetry

ENP11011 Eavan Boland and Modern Irish Poetry Module type Optional (approved module: MPhil in Irish Writing) Term / hours Hilary / 22 ECTS 10 Coordinator(s) Dr Rosie Lavan ([email protected]) Dr Tom Walker ([email protected]) Lecturer(s) Dr Rosie Lavan Dr Tom Walker Cap Depending on demand Module description Eavan Boland is one of the most significant Irish poets of the past century. In a career of more than 50 years, she persistently questioned, and radically expanded, the parameters of Irish poetry and the definition of the Irish poet. The course will examine a wide range of Eavan Boland’s poetry and prose. Seminars are structured around some of the poet’s major themes and modes. These will also be interspersed with seminars that seek to place Boland within the broader history of modern Irish poetry, via comparisons with the work and careers of Blanaid Salkeld, Patrick Kavanagh, Derek Mahon, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin and Paula Meehan. Also explored will be relevant historical and cultural contexts, and questions of poetics and ideology. Assessment The module is assessed through a 4,000-word essay. Indicative bibliography Students will need to purchase a copy of Eavan Boland, New Selected Poems (Carcanet/Norton) and Eavan Boland, Object Lessons: The Life of the Woman and the Poet in Our Time (Carcanet/Vintage/Norton) as the core course texts. Please note: it is expected that students will read Object Lessons in full before the start of the course. All other primary material needed through the term will be made available via Blackboard. This will include poems from Boland’s collections published since the appearance of New Collected Poems (Domestic Violence, A Woman Without A Country and The Historians) and the work of the other poets to be studied on the course, as well as various other relevant essays, articles and interviews. -

THE WOOING of CHOICE: Prosimetric Reconstruction of the Female Journey in Irish Mythology

THE WOOING OF CHOICE: Prosimetric Reconstruction of the Female Journey in Irish mythology by Roxanne Bodsworth 2020 This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Institute of Sustainable Industries and Liveable Cities, Victoria University. i Abstract: In “The Wooing of Choice: prosimetric reconstruction of the female journey in Irish mythology”, I examine the representation of female characters in Irish mythological tales where the woman chooses her lover in contravention of social expectations. In the traditional versions, the woman recedes into the background as the narrative develops around the male hero. I ask what happens to the discourse of the narrative when it is subverted so that the focus is placed upon the female experience. This is explored through a creative component, called ‘Meet Me in My World’, a prosimetric reconstruction of three Irish tales in which the woman chooses her lover and compels him to follow her. The three tales are: Aislinge Óengusso (The Dream of Óengus); Tóruigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne (The Pursuit of Diarmaid and Gráinne); and Longes mac nUislenn (The Exile of the Sons of Uisliu). The exegetical component, comprising 50% of the thesis, is composed of two sections. In the first, I examine theories of feminist writing and remythologizing, and develop a new model for feminist reconstruction, which I apply to the creative product. In the second section, I explore the relationship between narrative and poetry, from medieval prosimetric translations to contemporary hybrid texts, and consider which form provides the best framework for my female-centred narrative and the verse. -

Downloaded from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil Na Héireann, Corcaigh

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Author(s) Lawlor, James Publication date 2020-02-01 Original citation Lawlor, J. 2020. A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2020, James Lawlor. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/10128 from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork A Cultural History of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Thesis presented by James Lawlor, BA, MA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork The School of English Head of School: Prof. Lee Jenkins Supervisors: Prof. Claire Connolly and Prof. Alex Davis. 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 4 Declaration .......................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 6 List of abbreviations used ................................................................................................... 7 A Note on The Great -

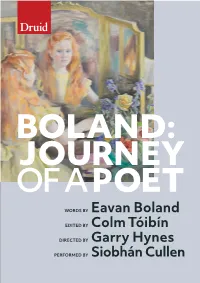

Boland Journey of a Poet Show Programme

BACK TO CONTENTS BOLAND: JOURNEY OF A POET WORDS BY Eavan Boland EDITED BY Colm Tóibín DIRECTED BY Garry Hynes PERFORMED BY Siobhán Cullen 1 BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS Contents Cast and Creatives 5 Finding a voice ... 6 When Silence Is Broken 8 Eavan Boland 12 Production Team 14 Thank You 15 Biographies 17 Druid Staff 28 Druid Supporters 29 Druid Friends 30 Become a Friend 31 Rehearsal Photograph: Emilija Jefremova 2 3 BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS BACK TO CONTENTS CAST AND CREATIVES BOLAND: JOURNEY OF A POET A Druid at Home production LIVE STREAM PERFORMANCES 22 – 24 APRIL 2021 AVAILABLE ON DEMAND 27 APRIL – 2 MAY 2021 WORDS BY Eavan Boland EDITED BY Colm Tóibín DIRECTED BY Garry Hynes PERFORMED BY Siobhán Cullen DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY Colm Hogan SET DESIGNER Francis O’Connor COSTUME DESIGNER Clíodhna Hallissey SOUND DESIGNER Sinéad Diskin COMPOSER Conor Linehan PORTRAIT ARTIST Debbie Chapman DURATION 60 minutes approximately with no interval JOIN THE CONVERSATION @DruidTheatre #BolandJourneyOfAPoet #DruidAtHome Rehearsal Photograph: Emilija Jefremova 4 5 BACK TO CONTENTS PROGRAMME NOTE PROGRAMME NOTE Much later, when I was preparing my Inaugural Address as ‘Finding a voice where President, I told Eavan I wanted to refer to women who had been outside history – a phrase we had both discussed together. She they found a vision’ gave me the lovely last line, from ‘The Singers’, which she was still working on: ‘Finding a voice where they found a vision’. I am delighted that Druid is presenting Boland: Journey of a Poet. Eavan had a great gift for friendship and I was lucky I visited Eavan several times in Stanford and came to know how enough to become a close friend when we were students loved and respected she was there. -

Beleaguered Spaces in Eavan Boland's Domestic Violence

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 18 | 2019 Guerre en poésie, poésie en guerre “This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence Bertrand Rouby Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/16298 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.16298 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Bertrand Rouby, ““This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence”, Miranda [Online], 18 | 2019, Online since 15 April 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/miranda/16298 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.16298 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. “This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence 1 “This sudden Irish fury”: beleaguered spaces in Eavan Boland’s Domestic Violence Bertrand Rouby 1 Since the 1960s, many are the poets who have tackled the period known as The Troubles, though few with as much emphasis on domesticity as Eavan Boland. Together with Seamus Heaney, Derek Mahon and Michael Longley, she is one of a handful of Irish writers who have managed to address the issue of domestic conflicts with an equally concise and vivid style of writing, using tropes related to personal and shared experience1. Drawing on metaphors and metonymies from everyday life and her immediate surroundings, Boland eschews the pitfalls of oblique or circuitous writing, even though her use of personal imagery makes for an indirect approach.