La Cenerentola Rossini’S Cinderella Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CINDERELLA Curriculum Connections California Content Standards Kindergarten Through Grade 12

San Francisco Operaʼs Rossiniʼs CINDERELLA Curriculum Connections California Content Standards Kindergarten through Grade 12 LANGUAGE ARTS WORD ANALYSIS, FLUENCY, AND VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT Phonics and Phonemic Awareness: Letter Recognition: Name the letters in a word. Ex. Cinderella = C-i-n-d-e-r-e-l-l-a. Letter/Sound Association: Name the letters and the beginning and ending sound in a word. C-lorind-a Match and list words with the same beginning or ending sounds. Ex. Don Ramiro and Dandini have the same beginning letter “D” and sound /d/; but end with different letters and ending sounds. Additional examples: Don Ramiro, Don Magnifico, Alidoro; Cinderella, Clorinda. Syllables: Count the syllables in a word. Ex.: Cin-der-el-la Match and list words with the same number of syllables. Clap out syllables as beats. Ex.: 1 syllable 2 syllables 3 syllables bass = bass tenor = ten-or soprano = so-pra-no Phoneme Substitution: Play with the beginning sounds to make silly words. What would a “boprano” sound like? (Also substitute middle and ending sounds.) Ex. soprano, boprano, toprano, koprano. Phoneme Counting: How many sounds in a word? Ex. sing = 4 Phoneme Segmentation: Which sounds do you hear in a word? Ex. sing = s/i/n/g. Reading Skills: Build skills using the subtitles on the video and related educator documents. Concepts of Print: Sentence structure, punctuation, directionality. Parts of speech: Noun, verb, adjective, adverb, prepositions. Vocabulary Lists: Ex. Cinderella, Opera glossary, Music and Composition terms Examine contrasting vocabulary. Find words in Cinderella that are unfamiliar and find definitions and roots. Find the definitions of Italian words such as zito, piano, basta, soto voce, etcetera, presto. -

La Cenerentola SYNOPSIS

Gioachino Rossini’s La Cenerentola SYNOPSIS Act I While her sisters Clorinda and Tisbe live like princesses, Angelina (known as “Cenerentola,” or Cinderella) is reduced to household drudgery. A hungry beggar appears at their door, and Angelina alone treats him with kindness. When word arrives that the prince, Don Ramiro, intends to choose his bride at a ball that very evening, the girls’ father, Don Magnifico, envisions a glorious future and urges Clorinda and Tisbe to make a good impression. When the house is quiet, Don Ramiro himself enters, disguised as a servant. His tutor Alidoro—the disguised beggar—has informed him that his perfect bride resides there. Ramiro’s valet, Dandini, arrives in rich garments, claiming to be the prince. Ramiro marvels at the shy beauty dressed in rags, but Don Magnifico orders Angelina to stay home while the others head off to the ball. Angelina is left behind with Alidoro, who consoles her, then escorts her to the ball. Clorinda and Tisbe fail miserably in their attempt to make a good impression on the disguised Dandini, succeeding only in convincing Ramiro that they are conceited fools. Alidoro arrives at the ball with Angelina, whom nobody recognizes dressed in her elegant gown. Act II At the ball, Dandini pursues Angelina, who finally tells the “prince” that she is in love with someone else—his own servant. Overhearing this, Ramiro rushes forward and declares his love. She tells him that she is not at all what she seems. Giving him one of her bracelets, she leaves, telling him that he must seek her out. -

Faculty Recital: Zachary James, Bass Zachary James

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 11-6-2015 Faculty Recital: Zachary James, bass Zachary James Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation James, Zachary, "Faculty Recital: Zachary James, bass" (2015). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1317. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1317 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Faculty Recital: Zachary James, Bass Richard Montgomery, Piano Hockett Family Recital Hall Friday, November 6th, 2015 7:00 pm Program A Little Music Gustav Holst 1874-1934 Humbert Wolf 1885-1940 Là del ciel nell'arcano profondo Gioachino Rossini from La Cenerentola 1792-1868 Jacopo Ferretti 1784-1852 Je t'implore Ambroise Thomas from Hamlet 1811-1896 Michel Carré 1821-1872 Jules Barbier 1825-1901 Scintille, diamant Jacques Offenbach from Les Contes d'Hoffmann 1819-1880 Jules Barbier 1825-1901 Tritt ohne Zagen ein, mein Kind Karl Goldmark from Die Königin von Saba 1830-1915 Hermann Salomon Mosenthal 1821-1877 O, wie will ich triumphieren Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart from Die Entführung aus dem Serail 1756-1791 Christoph Friedrich Bretzner 1748-1807 I'm fixin' to tell y' 'bout a feller I knowed Carlisle Floyd I'm a lonely man, Susannah 1926- Hear me, O Lord from Susannah Intermission -

CINDERELLA Websites

GIOACHINO ROSSINIʼS CINDERELLA Links to resources and lesson plans related to Rossiniʼs opera, Cinderella. The Aria Database: La Cenerentola http://www.aria- database.com/search.php?sid=e2dbb31103303fb8f096f9929cf13345&X=1&dT=Full&fC=1&searching=yes&t0=all &s0=Cenerentola&f0=keyword&dS=arias Information on 9 arias for La Cenerentola, including roles, voice parts, vocal range, synopsisi, with aria libretto and translation. Great Performances at the Met: La Cenerentola http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/gp-at-the-met-la-cenerentola/3461/ Joyce DiDonato sings the title role in Rossiniʼs Cinderella story, La Cenerentola, with bel canto master Juan Diego Flórez as her dashing prince. The Guardian: Glyndebourne: La Cenerentola's storm scene - video http://www.theguardian.com/music/video/2012/jun/18/glyndebourne-2012-la-cenerentola-video Watch the storm scene in this extract from Glyndebourne's 2005 production of Rossini's La Cenerentola, directed by Peter Hall. IMSLP / Petrucci Music Library: La Cenerentola http://imslp.org/wiki/La_cenerentola_(Rossini,_Gioacchino) Read online or download full music scores and vocal scores for La Cenerentola, music by Gioacchino Rossini. Internet Archive: La Ceniecineta: opera en tres actos https://archive.org/details/lacenicientaoper443ferr Spanish Translation of La Cenerentola, 1916. Internet Archive: La Cenerentola: Dramma Giocoso in Due Atti (published 1860) https://archive.org/stream/lacenerentoladra00ross_0#page/n1/mode/2up Read online or download .pdf of libretto for Rossiniʼs opera, La Cenerentola. In Italian with English Translation. The Kennedy Center: Washington National Opera: La Cenerentola https://www.kennedy-center.org/events/?event=OPOSD Francesca Zambello discusses Rossiniʼs opera, Cinderella. Lyric Opera of Chicago: Cinderella Backstage Pass! https://www.lyricopera.org/uploadedFiles/Education/Children_and_Teens/2011- 12%20OIN%20Backstage%20Pass%20color.pdf Cinderella is featured in Backstage Pass, Lyric Opera of Chicagoʼs student magazine. -

8.660277-78 Bk Rossini La Gazzetta EU

8.660277-78 bk Rossini La gazzetta US 20-07-2010 8:48 Pagina 24 2 CDs Also Available ROSSINI La gazzetta Marco Cristarella Orestano • Judith Gauthier Giulio Mastrototaro • Michael Spyres • Rossella Bevacqua Vincenzo Bruzzaniti • Maria Soulis San Pietro a Majella Chorus, Naples Czech Chamber Soloists, Brno • Christopher Franklin 8.660087-88 8.660203-04 8.660233-34 8.660277-78 24 8.660277-78 bk Rossini La gazzetta US 20-07-2010 8:48 Pagina 2 %ebenfalls lächerlich kostümiert. Liebe liegt in der Luft. zukünftige Gemahlin, und Don Pomponio hat Lisetta Wie die andern zuvor, vermag Don Pomponio die noch immer nicht gefunden. Madama La Rose tritt auf ^maskierten Tänzer nicht voneinander zu unterscheiden. und meldet, dass die Mädchen nunmehr vermählt seien. Gioachino Er weiß nicht, wer von ihnen seine Tochter ist. *Sie bittet, ihnen zu vergeben. Alberto und Filippo wollen inzwischen bei ihren Doralice und Alberto erbitten Anselmo um ROSSINI jeweiligen Partnerinnen bleiben, Doralice fürchtet die Verzeihung, Lisetta und Filippo wenden sich (1792-1868) Reaktion ihres Vaters. Don Pomponio ist darauf gleichermaßen an Don Pomponio – und endlich bedacht, für seine Tochter den türkischen Bewerber zu gewähren die Väter Pardon. Alle sind fest entschlossen, finden. Nach wie vor sucht er Lisetta. Die andern setzen sich jeden Tag an die Zeitung zu erinnern. La gazzetta alles daran, ihn noch weiter zu verwirren. Die Liebenden Dramma per musica in two acts by Giuseppe Palomba &machen sich aus dem Staub. Keith Anderson Critical edition by the Fondazione Rossini, edited by Philip Gossett and Fabrizio Scipioni (Ricordi BMG) Anselmo sucht seine Tochter, Traversen seine Deutsche Fassung: Cris Posslac Reconstruction of the 1st Act Quintet by the Deutsche Rossini Gesellschaft, edited by Stefano Piana Don Pomponio Storione . -

La Cenerentola – Where Music Meets Drama

Fairy Tales in Performance: La Cenerentola – Where Music Meets Drama Cecilia Hann Introduction As a chorus teacher for 20 years, I see the importance of singing as a group to facilitate happiness, consolation, entertainment and a sense of community. When the seminar of “Stories in Performance: Drama, Fable, Story and the Oral Tradition” was offered by the Delaware Teacher Institute, I immediately wondered if I could incorporate the oral tradition into my singing groups. How could I teach my students stories while I am teaching them to sing? Remembering from my years of Music History at College Misericordia, opera is the foremost expression of music and drama. As I researched various operas such as “The Magic Flute” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, “Hansel and Gretel” by Engelbert Humperdinck and “The Flying Dutchman” by Richard Wagner, I discovered a quote from the libretto in the opera “La Cenerentola” by Rossini that sums up why drama can be so important to my students: “All of the world is a theatre, where all of us are actors.”1 Now that I know music and drama are necessary for my music program, I had to decide which opera would have significant role for my students. Not only should this opera be meaningful but my students should be able to connect and build background. I chose “La Cenerentola” because it is similar to “Cinderella.” which most of my students know from the Disney or television version. By building on their knowledge of “Cinderella,” we can investigate the similarities and differences to Rossini’s “La Cenerentola. They can explore music in addition to tapping into the human emotions through acting out the story. -

Short Operas for Educational Settings: a Production Guide

SHORT OPERAS FOR EDUCATIONAL SETTINGS A PRODUCTION GUIDE by Jacquelyn Mouritsen Abbott Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2020 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee Patricia Stiles, Research Director and Chair Gary Arvin Jane Dutton Dale McFadden 10 April 2020 ii Copyright ⃝c 2020 Jacquelyn Mouritsen Abbott iii To my dearest love, Marc – my duet partner in life and in song iv Acknowledgements I am deeply grateful to my research director Patricia Stiles, for her devoted teaching, help, care, and guidance. I have learned so much from you throughout the years and am profoundly grateful for your kindness and your mentorship. I am deeply indebted to Dale McFadden, Gary Arvin, and Jane Dutton—it was a great honor to have you on my committee. I offer sincerest thanks to all of the composers and librettists who sent me scores, librettos, or recordings and who answered my questions and allowed me to use musical examples from their works. These exceptional artists include Dan Shore, Michael Ching, Leanna Kirchoff, Harry Dunstan, Kay Krekow, Milton Granger, Thomas Albert, Bruce Trinkley, John Morrison, Evan Mack, Errollyn Wallen, and Paul Salerni. I also owe a special thank you to ECS publishing for allowing me to use musical examples from Robert Ward’s Roman Fever. Thanks to Pauline Viardot, Jacques Offenbach, and Umberto Giordano for inspiring the musical world for the past 150-plus years. -

Cenerentola (Italy) the Magic Orange Tree (Haiti)

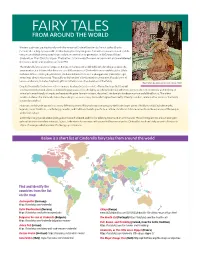

FAIRY TALES FROM AROUND THE WORLD Western audiences are most familiar with the version of Cinderella written by French author Charles Perrault, who is largely responsible for developing the fairy tale genre. Perrault's stones were based on folk tales, most of which were passed down orally from generation to generation. In 1697, he published Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper. The Brothers Grimm wrote their own version in 1812 and were followed themselves by the animated Disney film in 1950. The Cinderella fairy tale is not unique to Europe or the Western world. While scholars disagree about the exact number, it is believed that there are over 800 variations of Cinderella from around the globe. While each one differs in setting or plot details, the basic outline is the same: a young person (most often a girl, sometimes a boy is mistreated. They suffer at the hands of a family member whose own lifestyle is one of leisure or idleness, and who may lavish gifts and attention on other members of the family. Illustration by Anne Anderson (1874-1930) Despite the cruelty, the heroine or hero remains kind hearted and modest, often in the hope that they will one day receive love and affection. A valuable prize is put before the family and the wicked one’s scheme to win it. In the end, Cinderella, with the help of animal or human friends, triumphs and receives the prize. In most versions, the prize IS the love of a handsome prince and a life of luxury. The widest variation between the Cinderella tales is the ending: in some versions, Cinderella forgives the cruelty of family members, while in other versions, the family is severely punished. -

La Cenerentola

| What to Exp Ect from la cenerentola thE prEmise is simple: a young WomaN denigrated By hEr THE WORK own family meets a prince who recognizes her true beauty. Rossini’s operatic La cenerentoLa version of the Cinderella tale—“Cenerentola” in Italian—is charming, an opera in two acts, sung in Italian beautiful, touching, and dramatically convincing, propelled by soaring music by Giachino rossini melodies and laced with humor both subtle and broad. Libretto by Jacopo ferretti, after In Western culture, the name Cinderella may bring to mind an animated charles perrault’s cendrillon and film or a child’s bedtime reading, but the story is universal across time librettos by charles-Guillaume Etienne and francesco fiorini and continents. Long before the Brothers Grimm and Walt Disney came along, dozens of versions were told in many countries, including a Chinese first performed on January, 1817 in rome, Italy Cinderella created more than a thousand years ago. Every interpretation is different, and Rossini’s La Cenerentola is no pROducTiOn exception. Surprisingly, it’s not even a fairy tale. The composer and his fabio Luisi, conductor librettist, Jacopo Ferretti, tell the story without a hint of magic. There are no mice that turn into coachmen, no pumpkin that turns into a coach. cesare Lievi, production There’s no fairy godmother. And as your students will discover, there’s not maurizio Balo, Set and costume even the telltale glass slipper. Designer La Cenerentola is a fable of human nature. Rossini’s humane, realistic Gigi Saccomandi, Lighting Designer approach transcends the work’s fairy-tale roots. -

Don Giovanni Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards

Opera Box 620 North First Street, Minneapolis, MN 55401 Kevin Ramach, PRESIDENT AND GENERAL DIRECTOR Dale Johnson, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Educator, Thank you for using a Minnesota Opera Opera Box. This collection of material has been designed to help any educator to teach students about the beauty of opera. This collection of material includes audio and video recordings, scores, reference books and a Teacher’s Guide. The Teacher’s Guide includes Lesson Plans that have been designed around the materials found in the box and other easily obtained items. In addition, Lesson Plans have been aligned with State and National Standards. See the Unit Overview for a detailed explanation. Before returning the box, please fill out the Evaluation Form at the end of the Teacher’s Guide. As this project is new, your feedback is imperative. Comments and ideas from you – the educators who actually use it – will help shape the content for future boxes. In addition, you are encouraged to include any original lesson plans. The Teacher’s Guide is intended to be a living reference book that will provide inspiration for other teachers. If you feel comfortable, include a name and number for future contact from teachers who might have questions regarding your lessons and to give credit for your original ideas. You may leave lesson plans in the Opera Box or mail them in separately. Before returning, please double check that everything has been assembled. The deposit money will be held until I personally check that everything has been returned (i.e. CDs having been put back in the cases). -

Presenta: La Cenicienta

pprreesseennttaa:: LLaa CCeenniicciieennttaa Ópera de Gioacchino Rossini GUÍA DIDÁCTICA Guía didáctica de La Cenicienta (Rossini - Comediants): M. Antònia Guardiet IInnttrroodduucccciióónn La Cenicienta es una ópera que reúne todos los ingredientes musicales del compositor belcantista Gioacchino Rossini (1792 – 1868). A lo largo de la representación escucharemos: arias, interpretadas por la brillante protagonista Cenicienta, repletas de ornamentaciones —coloraturas—; melodías rítmicas y cómicas, bufas, en boca del padrastro Don Magnífico o del lacayo Dandini; arias cargadas de nobleza y de florituras vocálicas. La música de Rossini nos deleitará con: - momentos de serenidad y melancolía (Cenicienta: Érase una vez un rey…) - melodías alegres y decididas (Dandini: Del príncipe, lacayo soy…) - fragmentos cómicos de una gran riqueza rítmica (Don Magnífico: Cada vez que me dormía: cuchicheo sin parar...) - momentos de intenso dramatismo (Concertante: Yo quiero ir a bailar…) - duetos de amor (Dueto de Ramiro y Cenicienta: He notado una explosión…) La producción de la ópera La Cenicienta lleva el sello escénico de la Compañía Comediants. Su director, Joan Font, ha realizado la adaptación de la ópera original La C enerentola de Rossini llevando a cabo una curiosa, divertida, comprensible y original reducción para niños. La puesta en escena ha conseguido reunir los momentos musicales y plásticos más significativos: - el movimiento de los personajes, reforzado por sus voces, que expresan la acción de una historia harto conocida, pero con ingredientes -

LA CENERENTOLA SAISON 14-15 Symphonique Fiche Pédagogique

ROSSINI LA CENERENTOLA SAISON 14-15 Symphonique Fiche pédagogique Rossini LA CENERENTOLA Quelques mots entre vous et nous… Pour profiter au maximum du spectacle, voici des informations géné- rales et quelques recommandations à destination de vos élèves : Nous sommes très heureux de vous accueillir à l’Opéra de Rouen Haute-Normandie pour La Cenerentola de Rossini. Cet Opéra sera Informations générales peut-être une première expérience pour certains de vos élèves, une • Pour les séances scolaires, le placement se fait en fonction du ni- expérience renouvelée pour d’autres, nous espérons qu’il sera en tout veau de classe afin d’offrir à tous la meilleure visibilité. Nous vous -re cas un moment de découverte, d’éveil et de ressenti partagé. mercions de respecter les places qui vous seront proposées par notre personnel d’accueil. Cette fiche pédagogique a pour vocation de vous donner les repères • N’oubliez pas de nous prévenir en amont si vous avez besoin de clefs pour préparer vos élèves à cette sortie. Vous y trouverez quelques places supplémentaires. pistes vous permettant d’approfondir le travail en classe ou d’échanger • Les élèves sont sous la responsabilité des enseignants et des ac- simplement avec vos élèves avant et / ou après votre venue au Théâtre compagnateurs. Nous vous remercions de rester près d’eux afin de des Arts. Parce qu’un spectacle se prépare, se vit et se prolonge en- veiller à la bonne écoute du spectacle et au respect de tous. semble, n’hésitez pas à nous faire part de vos remarques et à nous communiquer les réactions de vos élèves.