Iqbal As Political Poet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam

The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam Muhammad Iqbal The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam written by Muhammad Iqbal Published in 1930. Copyright © 2009 Dodo Press and its licensors. All Rights Reserved. CONTENTS • Preface • Knowledge and Religious Experience • The Philosophical Test of the Revelations of Religious Experience • The Conception of God and the Meaning of Prayer • The Human Ego - His Freedom and Immortality • The Spirit of Muslim Culture • The Principle of Movement in the Structure of Islam • Is Religion Possible? PREFACE The Qur‘an is a book which emphasizes ‘deed‘ rather than ‘idea‘. There are, however, men to whom it is not possible organically to assimilate an alien universe by re-living, as a vital process, that special type of inner experience on which religious faith ultimately rests. Moreover, the modern man, by developing habits of concrete thought - habits which Islam itself fostered at least in the earlier stages of its cultural career - has rendered himself less capable of that experience which he further suspects because of its liability to illusion. The more genuine schools of Sufism have, no doubt, done good work in shaping and directing the evolution of religious experience in Islam; but their latter-day representatives, owing to their ignorance of the modern mind, have become absolutely incapable of receiving any fresh inspiration from modern thought and experience. They are perpetuating methods which were created for generations possessing a cultural outlook differing, in important respects, from our own. ‘Your creation and resurrection,‘ says the Qur‘an, ‘are like the creation and resurrection of a single soul.‘ A living experience of the kind of biological unity, embodied in this verse, requires today a method physiologically less violent and psychologically more suitable to a concrete type of mind. -

Directorate of Distance Learning, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan

Directorate of Distance Learning, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan. SYLLABUS AND STUDY SCHEME FOR M.A. PAK-STUDIES Part-I (Session 2009-2011) PROPOSED SYLLABUS FOR M.A. PAK-STUDIES Part-I Paper-I (Compulsory) GEOGRAPHY OF PAKISTAN (100 Marks)=(20% Assignments + 80% Theory) The course on the Geography of Pakistan is meant to educate the students in the areal dimensions and natural contents of their homeland. The course has been developed under two broad headings. (a) The Natural Environment. (b) Man and Environment: (a) Firstly the Natural Environment. It covers hypsography, hydrology, climate, soil and their development and classification. (b) Secondly, Man in relation to Environment. The themes are suggestive and cover man’s relation to agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining and industry as well as communication, trade, population and settlements. 1-: Importance of Geo-political factors & Views of some Geo-political thinkers: (a) Mahaan (b) Mackinder (c) Harshome (d) Hauschoffer. 2-: Physical characteristics or the Natural Environment of Pakistan: Mountains; Plains, Plateaus and Deserts. 3-: Hydrology: The Indus System, Drainage Pattern of Baluchistan; Natural and 4-: Climate and Weather: Climatic Elements; Temperature, Rainfall, Air Pressure and Winds-Climatic Divisions. 5-: Soils: Factors of soil formation in Pakistan: Soil classification in Pakistan. 6-: Natural vegetation: Types of forests. 7-: Resources: Mineral and Power Resources. 8-: Agriculture: Livestock-agricultural performance and problems of principal crops, Live-stock. 9-: Industries: Industrial Policy: Industrial Development Factory Industries-Cottage Industries. 10-: Transport and Foreign Trade: Transport-Trade and Commerce-Export and Import. 11-: Population: Growth of Population Urban and Rural Population-Important urban centers. List of Readings: 1. -

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders Nation The word “NATION” is derived from Latin route “NATUS” of “NATIO” which means “Birth” of “Born”. Therefore, Nation implies homogeneous population of the people who are organized and blood-related. Today the word NATION is used in a wider sense. A Nation is a body of people who see part at least of their identity in terms of a single communal identity with some considerable historical continuity of union, with major elements of common culture, and with a sense of geographical location at least for a good part of those who make up the nation. We can define nation as a people who have some common attributes of race, language, religion or culture and united and organized by the state and by common sentiments and aspiration. A nation becomes so only when it has a spirit or feeling of nationality. A nation is a culturally homogeneous social group, and a politically free unit of the people, fully conscious of its psychic life and expression in a tenacious way. Nationality Mazzini said: “Every people has its special mission and that mission constitutes its nationality”. Nation and Nationality differ in their meaning although they were used interchangeably. A nation is a people having a sense of oneness among them and who are politically independent. In the case of nationality it implies a psychological feeling of unity among a people, but also sense of oneness among them. The sense of unity might be an account, of the people having common history and culture. -

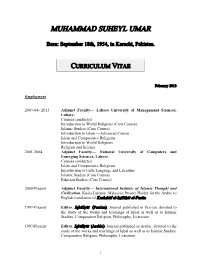

Muhammad Suheyl Umar

MUHAMMAD SUHEYL UMAR Born: September 18th, 1954, in Karachi, Pakistan. CURRICULUM VITAE February 2013 Employment 2003-04– 2013 Adjunct Faculty— Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore. Courses conducted: Introduction to World Religions (Core Course) Islamic Studies (Core Course) Introduction to Islam —Advanced Course Islam and Comparative Religions Introduction to World Religions Religion and Science 2001-2004 Adjunct Faculty— National University of Computers and Emerging Sciences, Lahore. Courses conducted: Islam and Comparative Religions Introduction to Urdu Language and Literature Islamic Studies (Core Course) Pakistan Studies (Core Course) 2000-Present Adjunct Faculty— International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Project Holder for the Arabic to English translation of Kashsh«f al-IÄÇil«Á«t al-Funën. 1997-Present Editor, Iqb«liy«t (Persian); Journal published in Persian, devoted to the study of the works and teachings of Iqbal as well as to Islamic Studies, Comparative Religion, Philosophy, Literature. 1997-Present Editor, Iqb«liy«t (Arabic); Journal published in Arabic, devoted to the study of the works and teachings of Iqbal as well as to Islamic Studies, Comparative Religion, Philosophy, Literature. 1 1997-Present Director, Iqbal Academy Pakistan, a government research institution for the works and teachings of Iqbal, the poet Philosopher of Pakistan who is the main cultural force and an important factor in the socio- political dynamics of the people of the Sub-continent. 1997-Present Editor, Iqbal Review, Iqb«liy«t; Quarterly Journals, published alternately in Urdu and English, devoted to the study of the works and teachings of Iqbal as well as to Islamic Studies, Comparative Religion, Philosophy, Literature, History, Arts and Sociology. -

Picture of Muslim Politics in India Before Wavell's

Muhammad Iqbal Chawala PICTURE OF MUSLIM POLITICS IN INDIA BEFORE WAVELL’S VICEROYALTY The Hindu-Muslim conflict in India had entered its final phase in the 1940’s. The Muslim League, on the basis of the Two-Nation Theory, had been demanding a separate homeland for the Muslims of India. The movement for Pakistan was getting into full steam at the time of Wavell’s arrival to India in October 1943 although it was opposed by an influential section of the Muslims. This paper examines the Muslim politics in India and also highlights the background of their demand for a separate homeland. It analyzes the nature, programme and leadership of the leading Muslim political parties in India. It also highlights their aims and objectives for gaining an understanding of their future behaviour. Additionally, it discusses the origin and evolution of the British policy in India, with special reference to the Muslim problem. Moreover, it tries to understand whether Wavell’s experiences in India, first as a soldier and then as the Commander-in-Chief, proved helpful to him in understanding the mood of the Muslim political scene in India. British Policy in India Wavell was appointed as the Viceroy of India upon the retirement of Lord Linlithgow in October 1943. He was no stranger to India having served here on two previous occasions. His first-ever posting in India was at Ambala in 1903 and his unit moved to the NWFP in 1904 as fears mounted of a war with 75 76 [J.R.S.P., Vol. 45, No. 1, 2008] Russia.1 His stay in the Frontier province left deep and lasting impressions on him. -

Syllabus for MA History (Previous)

Syllabus for M.A History (Previous) Compulsory Paper I: Muslim Freedom Movement in India 1857-1947 Events: The War of Independence and its Aftermath – the Indian National Congress and the Muslims of India – The Aligarh Movement, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: Political, Educational and Literary Services, the Deoband Movement and its role in the socio-political and educational progress of Indian Muslims, the partition of Bengal – the Simla Deputation – the creation of All India Muslim League – Nawab Mohsin ul Mulk and Nawab Waqar ul Mulk: their services to the cause of Indian Muslims, Syed Ameer Ali: Political and literary achievements and services, the Indian Councils Act of 1909, Hindu Muslim Unity and the Lucknow Pact – the Khilafat and Hijrat Movements – Maulana Mohammad Ali Jauhar: Services and Achievements, the Government of India Act 1919, the Simon Commission and the Nehru Report – Political Philosophy of Allama Mohammad Iqbal, Iqbal’s Allahabad Address – Round Table Conference 1930-1932 (First Session, Gandhi Irwin Pact and the Second Session, The Communal Award of 1932 and the Third Session) – Government of India Act 1935 – the Elections of 1937 and the Congress Rule in the provinces – the Lahore Resolution – Cripps Mission – Cabinet Mission – June 3rd Plan – the Controversy about the Governor- Generalship of Pakistan – Mohammad Ali Jinnah: Leadership and Achievements, the Radcliffe Boundary Commission Award Recommended Readings: Ishtiaq Hussain Qureshi, Struggle for Pakistan. Karachi: University of Karachi, 1969. Dr. Waheed-uz- Zaman, Towards Pakistan. Lahore: Publishers United Ltd., nd. Adbul Hamid, Muslim Separtism in India. Lahore: Oxford University Press, 1971. Khalid Bin Sayeed, Pakistan: The Formative Phase 1857-1948. -

IQBAL REVIEW Journal of the Iqbal Academy, Pakistan

QBAL EVIEW I R Journal of the Iqbal Academy, Pakistan October 1984 Editor Mirza Muhammad Munawwar IQBAL ACADEMY PAKISTAN Title : Iqbal Review (October 1984) Editor : Mirza Muhammad Munawwar Publisher : Iqbal Academy Pakistan City : Lahore Year : 1984 DDC : 105 DDC (Iqbal Academy) : 8U1.66V12 Pages : 188 Size : 14.5 x 24.5 cm ISSN : 0021-0773 Subjects : Iqbal Studies : Philosophy : Research IQBAL CYBER LIBRARY (www.iqbalcyberlibrary.net) Iqbal Academy Pakistan (www.iap.gov.pk) 6th Floor Aiwan-e-Iqbal Complex, Egerton Road, Lahore. Table of Contents Volume: 25 Iqbal Review: October 1984 Number: 3 1. PROOFS OF ISLAM ................................................................................................................... 4 2. REFLECTIONS ON QURANIC EPISTEMOLOGY ...................................................... 13 3. "IBLIS" IN IQBAL'S PHILOSOPHY ................................................................................... 31 4. ALLAMA IQBAL AND COUNCIL OF STATE ............................................................... 66 5. THEISTIC ONTOLOGY IN RADHAKRISHNAN AND IQBAL .............................. 71 6. REFLECTIONS ON IDEOLOGICAL SENTIMENTALISM ....................................... 87 7. ISLAM AND MODERN HUMANISM .............................................................................. 107 8. IDEALS AND REALITIES OF ISLAM............................................................................. 118 9. IQBAL—EPOCH-MAKING POET-PHILOSOPHER ................................................. 129 10. INDEX OF -

Iqbal's Response to Modern Western Thought: a Critical Analysis

International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences p-ISSN: 1694-2620 e-ISSN: 1694-2639 Vol. 8 No. 5, pp. 27-36, ©IJHSS Iqbal’s Response to Modern Western Thought: A Critical Analysis Dr. Mohammad Nayamat Ullah Associate Professor Department of Arabic University of Chittagong, Bangladesh Abdullah Al Masud PhD Researcher Dept. of Usuluddin and Comparative Religion International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM) ABSTRACT Muhammad Iqbal (1873-1938) is a prominent philosopher and great thinker in Indian Sub- continent as well as a dominant figure in the literary history of the East. His thought and literature are not simply for his countrymen or for the Muslim Ummah alone but for the whole of humanity. He explores his distinctive thoughts on several issues related to Western concepts and ideologies. Iqbal had made precious contribution to the reconstruction of political thoughts. The main purpose of the study is to present Iqbal‟s distinctive thoughts and to evaluate the merits and demerits of modern political thoughts. The analytical, descriptive and criticism methods have been applied in conducting the research through comprehensive study of his writings both in the form of prose and poetry in various books, articles, and conferences. It is expected that the study would identify distinctive political thought by Iqbal. It also demonstrates differences between modern thoughts and Iqbalic thoughts of politics. Keywords: Iqbal, western thoughts, democracy, nationalism, secularism 1. INTRODUCTION Iqbal was not only a great poet-philosopher of the East but was also among the profound, renowned scholars and a brilliant political thinker in the twentieth century of the world. -

Main Philosophical Idea in the Writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938)

Durham E-Theses The main philosophical idea in the writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938) Hassan, Riat How to cite: Hassan, Riat (1968) The main philosophical idea in the writings of Muhammad Iqbal (1877 - 1938), Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7986/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk im MIN PHILOSOPHICAL IDEAS IN THE fffilTINGS OF m^MlfAD •IQBAL (1877- 1938) VOLUME 2 BY EIFFAT I^SeAW Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts in the University of Durham for the Degree oi Doctor of Philosophy. ^lARCH 1968 Sohool of Oriental Studies, Blvet Hill, DURHAM. 322 CHAPTER VI THE DEVELOPMENT OF 'KHUDT' AMD IQBlL'S *MAED-E-MOMIN'. THE MEAMNQ OP *mJDT' Exp3.aining the meaning of the concept *KhudT', in his Introduction to the first edition of Asrar~e~ Kl^udT. -

Effect of Divergent Ideologies of Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Iqbal on Political Events in British India (1917-38)

M.L. Sehgal, International Journal of Research in Engineering, IT and Social Sciences, ISSN 2250-0588, Impact Factor: 6.565, Volume 09 Issue 01, January 2019, Page 315-326 Effect of Divergent Ideologies of Mahatma Gandhi and Muhammad Iqbal on Political Events in British India (1917-38) M. L. Sehgal (Fmrly: D. A. V. College, Jalandhar, Punjab (India)) Abstract: By 1917, Gandhi had become a front rung leader of I.N.C. Thereafter, the ‘Freedom Movement’ continued to swirl around him till 1947. During these years, there happened quite a number of political events which brought Gandhi and Iqbal on the opposite sides of the table. Our stress would , primarily, be discussing as to how Gandhi and Iqbal reacted on these political events which changed the psych of ‘British Indians’, in general, and the Muslims of the Indian Subcontinent in particular.Nevertheless, a brief references would, also, be made to all these political events for the sake of continuity. Again, it would be in the fitness of the things to bear in mind that Iqbal entered national politics quite late and, sadly, left this world quite early(21 April 1938), i.e. over 9 years before the creation of Pakistan. In between, especially in the last two years, Iqbal had been keeping indifferent health. So, he might not have reacted on some political happenings where we would be fully entitled to give reactions of A.I.M.L. and I.N.C. KeyWords: South Africa, Eghbale Lahori, Minto-Morley Reform Act, Lucknow Pact, Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms, Ottoman Empire, Khilafat and Non-Cooperation Movements, Simon Commission, Nehru Report, Communal Award, Round Table Conferences,. -

Iqbal Review

IQBAL REVIEW Journal of the Iqbal Academy Pakistan Volume: 52 April/Oct. 2011 Number:2, 4 Pattern: Irfan Siddiqui, Advisor to Prime Minister For National History & Literary Heritage Editor: Muhammad Sohail Mufti Associate Editor: Dr. Tahir Hameed Tanoli Editorial Board Advisory Board Dr. Abdul Khaliq, Dr. Naeem Munib Iqbal, Barrister Zaffarullah, Ahmad, Dr. Shahzad Qaiser, Dr. Dr. Abdul Ghaffar Soomro, Prof. Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Dr. Fateh Muhammad Malik, Dr. Khalid Masood, Dr. Axel Monte Moin Nizami, Dr. Abdul Rauf (Germany), Dr. James W. James Rafiqui, Dr. John Walbrigde (USA), Morris (USA), Dr. Marianta Dr. Oliver Leaman (USA), Dr. Stepenatias (Russia), Dr. Natalia Alparslan Acikgenc (Turkey), Dr. Prigarina (Russia), Dr. Sheila Mark Webb (USA), Dr. Sulayman McDonough (Montreal), Dr. S. Nyang, (USA), Dr. Devin William C. Chittick (USA), Dr. Stewart (USA), Prof. Hafeez M. Baqai Makan (Iran), Alian Malik (USA), Sameer Abdul Desoulieres (France), Prof. Hameed (Egypt) , Dr. Carolyn Ahmad al-Bayrak (Turkey), Prof. Mason (New Zealand) Barbara Metcalf (USA) IQBAL ACADEMY PAKISTAN The opinions expressed in the Review are those of the individual contributors and are not the official views of the Academy IQBAL REVIEW Journal of the Iqbal Academy Pakistan This peer reviewed Journal is devoted to research studies on the life, poetry and thought of Iqbal and on those branches of learning in which he was interested: Islamic Studies, Philosophy, History, Sociology, Comparative Religion, Literature, Art and Archaeology. Manuscripts for publication in the journal should be submitted in duplicate, typed in double-space, and on one side of the paper with wide margins on all sides preferably along with its CD or sent by E-mail. -

T.C. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Felsefe Ve Din Bilimleri Anabilim Dali

T.C. SÜLEYMAN DEMİREL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ FELSEFE VE DİN BİLİMLERİ ANABİLİM DALI MUHAMMED İKBAL’DE DİNDARLIĞIN PSİKOLOJİSİ Zümrüd AFET 1230206168 YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN Prof. Dr. Hüseyin CERTEL ISPARTA-2018 (AFET, Zümrüd, Muhammed İkbal'de Dindarlığın Psikolojisi, Yüsek Lisans, Isparta 2018) ÖZET Bu tezin konusu asrımızın büyük düşünürlerinden biri olan Muhammed İkbal'de Dindarlığın Psikolojisidir. Çalışmamın amacı Muhammed İkbal’in Psikoloji ve Din Psikolojisi açısından konumunu belirlemek ve onun konuyla ilgili orjinal görüşlerini ortaya koymaktır. Çalışmam giriş, iki bölüm ve sonuçtan oluşmaktadır. Girişte, araştırmamızın temel konusu, önemi ve amacı hakkında bilgi verilmiştir. Daha sonra İkbal`in yaşadığı dönemin karakteristik özellikleri, Hayatı, İlmi ve Dini Şahsiyeti ve Eserleri ele alınmıştır. Birinci bölümde, Muhammed İkbal ve Temel Psikolojik Kavramlar tanıtılmış, ikinci bölümde ise Muhammed İkbal’in Dini Hayatın Psikolojisi ile ilgili fikirlerine yer verilmiştir..Çalışmamın sonuç kısmında ise Muhammed İkbal’in genel olarak Din Psikolojisine yaptığı özgün katkı ve en önemli konu olan “Benlik” anlayışı ile ilgili temel yaklaşımını sunmaya çalıştım. Anahtar Kelimeler: İkbal, Dindarlık, Düşünce, Benlik, Ego, Mistik Tecrübe. iii (AFET, Zümrüd, Religious Psychology of Muhammad Iqbal, Master’s Thesis, Isparta 2018) ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis is the Religious Psychology of Muhammad Iqbal, one of the great thinkers of our century. The purpose of my work is to determine the position of Muhammad Iqbal in terms of Psychology and Religion Psychology and to reveal his original opinions about this subject. The study entry consists of two parts and the result. In the introduction, we have been informed about the main topic of our research, its importance and purpose.