A Multi-Method Examination of Race, Class, Gender, Sexual Orientation, and Motivations for Participation in the Youtube-Based “It Gets Better Project”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 2021 June Complimentary May 2020 May Proactive Proactive Sophisticated Care Sophisticated Care

COMPLIMENTARY JUNEMAY 2021 2020 smithfieldtimesri.net Cameron VanNostrand, age 4, from Smithfield, visits his friends at Blackbird Farm. BOSTON MA BOSTON 55800 PERMIT NO. PERMIT PAID Our customers U.S. POSTAGE U.S. ECRWSS Local Postal Customer Postal Local are our owners. PRSRT STD PRSRT Federally insured by NCUA PROACTIVE PROACTIVE SOPHISTICATED CARE SOPHISTICATED CARE OUR PATIENTS ENJOY: OUR • Therapy PATIENTS up to 7 Days aENJOY: Week Raising the bar in the delivery • TherapyBrand New up State-of-the-artto 7 Days a Week Rehab Gym & Equipment Raisingof short-term the bar in rehabilitative the delivery • BrandIndividualized New State-of-the-art Evaluations & Rehab Treatment Gym Programs & Equipment ofand short-term skilled nursing rehabilitative care in • IndividualizedComprehensive Evaluations Discharge Planning& Treatment that Programs Begins on Day One and skilled nursing care in • ComprehensiveSemi-Private and Discharge Private Rooms Planning with that Cable Begins TV on Day One Northern Rhode Island • Semi-PrivateConcierge Services and Private Rooms with Cable TV Northern Rhode Island • Concierge Services CARDIAC ORTHOPEDIC PULMONARY REHABILITATION CARDIAC REHABILITATION ORTHOPEDIC PULMONARY CARE Under the REHABILITATION direction of a leading • Physicians REHABILITATION & Physiatrist On-Site • Tracheostomy Care CARE Cardiologist/Pulmonologist, our specialized Under the direction of a leading • PhysiciansIndividualized & Physiatrist Aggressive On-Site Rehab • TracheostomyRespiratory Therapists Care nurses provide care to patients -

Princess Diana, the Musical Inspired by Her True Story

PRINCESS DIANA, THE MUSICAL INSPIRED BY HER TRUE STORY Book by Karen Sokolof Javitch and Elaine Jabenis Music and Lyrics by Karen Sokolof Javitch Copyright © MMVI All Rights Reserved Heuer Publishing LLC, Cedar Rapids, Iowa Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that this work is subject to a royalty. Royalty must be paid every time a play is performed whether or not it is presented for profit and whether or not admission is charged. A play is performed any time it is acted before an audience. All rights to this work of any kind including but not limited to professional and amateur stage performing rights are controlled exclusively by Heuer Publishing LLC. Inquiries concerning rights should be addressed to Heuer Publishing LLC. This work is fully protected by copyright. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without permission of the publisher. Copying (by any means) or performing a copyrighted work without permission constitutes an infringement of copyright. All organizations receiving permission to produce this work agree to give the author(s) credit in any and all advertisement and publicity relating to the production. The author(s) billing must appear below the title and be at least 50% as large as the title of the Work. All programs, advertisements, and other printed material distributed or published in connection with production of the work must include the following notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Heuer Publishing LLC of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.” There shall be no deletions, alterations, or changes of any kind made to the work, including the changing of character gender, the cutting of dialogue, or the alteration of objectionable language unless directly authorized by the publisher or otherwise allowed in the work’s “Production Notes.” The title of the play shall not be altered. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-Up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms TOMSETT, Eleanor Louise Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26442/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Reflections on UK Comedy’s Glass Ceiling: Stand-up Comedy and Contemporary Feminisms Eleanor Louise Tomsett A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2019 Candidate declaration: I hereby declare that: 1. I have not been enrolled for another award of the University, or other academic or professional organisation, whilst undertaking my research degree. 2. None of the material contained in the thesis has been used in any other submission for an academic award. 3. I am aware of and understand the University's policy on plagiarism and certify that this thesis is my own work. The use of all published or other sources of material consulted have been properly and fully acKnowledged. 4. The worK undertaKen towards the thesis has been conducted in accordance with the SHU Principles of Integrity in Research and the SHU Research Ethics Policy. -

Glitter Bombing: Weapon of Choice for Gay Rights, Pro Choice Advocates

Glitter Bombing: Weapon of Choice for Gay Rights, Pro Choice Advocates Glitter bombing is a relatively recent phenomenon and has been adopted as a form of protest, particularly (but not exclusively) by gay rights activists and supporters. Glitter bombing is readily accessible via Ruin Days (www.ruindays.com), an online business that offers a variety of glitter bomb options, including envelopes and spring-loaded tubes. A spring-loaded glitter bomb tube can be purchased anonymously for $22.99, and Ruin Days will ship directly to the intended recipient. Ruin Days posts the following caveat: “Your billing information and email will appear nowhere on the package.” Although glitter bombing as an offense has yet to be codified, some legal officials argue glitter bombing is technically an assault and battery. The glitter bombing of public officials rose to prominence in 2011, when Newt Gingrich, Tim Pawlenty, Michele Bachmann, Karl Rove and Erik Paulson were all similarly glitter bombed. The common denominator among these political figures is a conservative orientation and opposition to gay rights, especially marriage equality. Recipients in Glitter bomb mailing tube (per open source) 2012 included Rick Santorum (on four separate occasions), Mitt Romney and Ron Paul. Mitt Romney’s bomber, a University of Colorado student, faced up to six months in jail and a fine of $1000. Glitter bombing was featured in the Season 3 premiere of Glee on September 20, 2011. Nebraska Congressman Jeff Fortenberry was glitter bombed on March 4, 2015, at his office in Lincoln. Fortenberry, a Republican Representative endorsed by Nebraska Right to Life, was targeted by a pro-choice group who included a note. -

Smokey Stumps in State, to Be Mugwump Candidate

Our Price — 10c Cheap A)! the news By all the fits thai fits ... that write it. rOLUME LV Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Virginia. Friday, April 4. 1969 25 "Death" Wilson To Be Smokey Stumps In State, MI Cadet Of Year To Be Mugwump Candidate Second "classman Kenneth R. to go to Africa and "take up the i Wilson has been chosen by the white man's burden" while enjoy- LEXINGTON (Tass)—Democra- VMI, Public Relations Office as ing himself killing the local inhab- tic Party powers were rocked yes- VMI's cadet of the year. Wilson's itants. terday as famed Lexington politi- picture will now replace the statue Excusing himself from the ques- cian B. McCluer Gilliam declared of Virginia Mourning Her Dead on tioning Wilson went over to the his intentions to run in the upcom- the crest of all official Institute window where he blasted, with his ing party gubernatorial primary. publications .357 magnum, a butterfly who's "The time has come for Virginia In the words of the PRO, Wil- noisy flapping had distrubed him. to wake up!" the beloved VMI pro- son best exemplities the ViSII Returning to the interviev/, fessor said, slamming a book onto ideals—he is the Institute's model Death exclaimed that killing had the floor and waking up a few re- cadet. Wilson has so adapted him- always been part of his life—when porters who were nodding in the self to the VMI life that he can four days old, he had beaten his back row. "We must stick to ths truly say "I love it here." Bar- nurse to death with a jar of Beech- subject ot the course," he said, re- racks is not merely his home away nt baby food. -

Revolutionary Games and Repressive Tolerance: on the Hopes and Limits of Ludic Citizenship

http://dx.doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2015.3.2.3.shepard European Journal of Humour Research 3 (2/3) 18–34 www.europeanjournalofhumour.org Revolutionary Games and repressive tolerance: on the hopes and limits of ludic citizenship Benjamin Shepard Human Services Dept., City University of New York [email protected] Abstract This essay considers examples of boisterous game play, including ludic movement activity and humour in the context of the Occupy Wall Street movement in the USA. This form of auto- ethnography makes use of the researcher’s feelings, inviting readers into the personal, emotional subjectivities of the author. In this case, the author explores games, play, and humour highlighting a few of the possibilities and limits of play as a mechanism of social change, looking at the spaces in which it controls and when it liberates. While play has often been relegated to the sports field and the behaviour of children, there are other ways of opening spaces for play for civic purposes and political mobilization. The paper suggests play as a resource for social movements; it adds life and joyousness to the process of social change. Without playful humour, the possibilities for social change are limited. Keywords: play, Occupy Wall Street, Marx, Burning Man, pie fights. 1. Introduction Art and activism overlap in countless ways throughout the history of art and social movements. This essay considers the ways games, humour and play intervene and support the process. Here, social reality is imagined as a game, in which social actors play in irreverent, often humorous ways. Such activity has multiple meanings. -

Santorum Gingrich Romney Paul

the wichitan feature 7 Wednesday January 25, 2012 thewichitan.com your campus/ your news THE KEY SOUTH CAROLINA All of these guys really wanted PAUL to win the South Carolina pri- SANTORUM Rep. (R-Tex.) Ron Paul mary election. But Newt Gingrich, Frm. Sen. (R-Penn.) Rick Santorum amidst a newly broken sex scandal, rose to THE SKINNY: The libertarian from Texas placed second in the New the top, winning by a wide margin. The vic- THE SKINNY: The former Senator from Pennsylvania has built a Hampshire caucus and third in Iowa. Paul’s supporters say he has tory is bound to propel him to take Florida campaign for the 2012 primaries based almost solely on bringing the started a “revolution” amongst young voters by addressing foreign next, as it has with most candidates who United States back to God. He hadn’t garnished much media atten- policy issues and by cautioning lawmakers to stay away from Iran. win in the South Carolina. From 1980 to tion until he placed first in the Iowa polls. 2008, the Republican candidate who won PROPS FOR: Being persistent (he’s been in this race three times) South Carolina has also won the nomina- PROPS FOR: Bringing sweatervests to the forefront of couture and thoughtfully questioning the role of big government in Ameri- tion from the party. The state has helped to popularity and not quitting the race after a brutal glitter bombing by can society. elect Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush and protesters. Geroge Bush to the United States presidency. WHY THE HATERS HATE: Paul attracts less attention from the Now Romney will have to fight an uphill WHY THE HATERS HATE: He’s been critisized for racist remarks media than other candidates and gets less time to speak during de- battle to take votes from the Gingrich camp. -

Wednesday November 14, 2012

Wednesday November 14, 2012 8:00 AM 002024 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM Dolphin Europe 7 - Third/Lobby Level SEMINAR: Celebrating the COMMunity that Diversely “Does Disney”: Multi -disciplinary and Multi -institutional Approaches to Researching and Teaching About the "World" of Disney Sponsor: Seminars Chairs: Mary-Lou Galician, Arizona State University; Amber Hutchins, Kennesaw State University Presenters: Emily Adams, Abilene Christian University Sharon D. Downey, California State Univ, Long Beach Erika Engstrom, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Sandy French, Radford University Mary-Lou Galician, Arizona State University Cerise L. Glenn, Univ of North Carolina, Greensboro Jennifer A. Guthrie, University of Kansas Jennifer Hays, University of Bergen, Norway Amber Hutchins, Kennesaw State University Jerry L. Johnson, Buena Vista University Lauren Lemley, Abilene Christian University Debra Merskin, University of Oregon David Natharius, Arizona State University Tracey Quigley Holden, University of Delaware Kristin Scroggin, University of Alabama, Huntsville David Zanolla, Western Illinois University 002025 8:00 AM to 12:00 PM Dolphin Europe 8 - Third/Lobby Level SEMINAR: COMMunity Impact: Defining the Discipline and Equipping Our Students to Make Everyday Differences Sponsor: Seminars Chair: Darrie Matthew Burrage, Univ of Colorado, Boulder Presenters: Jeremy R. Grossman, University of Georgia Margaret George, Univ of Colorado, Boulder Katie Kethcart, Colorado State University Ashton Mouton, Purdue University Emily Sauter, University of Wisconsin, Madison Eric Burrage, University of Pittsburgh 002027 8:00 AM to 3:45 PM Dolphin Europe 10 - Third/Lobby Level SEMINAR: The Dissertation Writing Journey Sponsor: Seminars Chairs: Sonja K. Foss, Univ of Colorado, Denver; William Waters, University of Houston, Downtown 8:30 AM 003007 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM Dolphin Oceanic 3 - Third/Lobby Level PC02: Moving Methodology: 2012 Organizational Communication Division Preconference Sponsor: Preconferences Presenters: Karen Lee Ashcraft, University of Colorado, Boulder J. -

Download 1 File

Starship Troopers by Robert Heinlein Table of Contents Starship Troopers Chapter 8 Chapter 1 Chapter 9 Chapter 2 Chapter 10 Chapter 3 Chapter 11 Chapter 4 Chapter 12 Chapter 5 Chapter 13 Chapter 6 Chapter 14 Chapter 7 Chapter 1 Come on, you apes! You wanta live forever? — Unknown platoon sergeant, 1918 I always get the shakes before a drop. I’ve had the injections, of course, and hypnotic preparation, and it stands to reason that I can’t really be afraid. The ship’s psychiatrist has checked my brain waves and asked me silly questions while I was asleep and he tells me that it isn’t fear, it isn’t anything important — it’s just like the trembling of an eager race horse in the starting gate. I couldn’t say about that; I’ve never been a race horse. But the fact is: I’m scared silly, every time. At D-minus-thirty, after we had mustered in the drop room of theRodger Young , our platoon leader inspected us. He wasn’t our regular platoon leader, because Lieutenant Rasczak had bought it on our last drop; he was really the platoon sergeant, Career Ship’s Sergeant Jelal. Jelly was a Finno-Turk from Iskander around Proxima — a swarthy little man who looked like a clerk, but I’ve seen him tackle two berserk privates so big he had to reach up to grab them, crack their heads together like coconuts, step back out of the way while they fell. Off duty he wasn’t bad — for a sergeant. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Strike One... DISCONTENTS WHY YOU NEED HONI SOIT SOUND HONI NEWS Is It Too Much? a Cover Photo, a News and That’S Fine

week two semester one 2013 strike one... honi soit honi International students getting (slightly less) screwed Pg 4 Top 5 Disney songs to have sex to Pg 8 Can the Aussie media handle The Guardian? Pg 11 SUDS and MUSE reviews Pg 14 DISCONTENTS WHY YOU NEED HONI SOIT SOUND HONI NEWS Is it too much? A cover photo, a news And that’s fine. The audiences of these disputes that overwhelm your cam- 5. Run for Union, Get story, letters, and three opinion pieces. papers are too vast to spend pages on pus, the politics that govern your stu- It’s a strike heavy edition, that’s for sure. something so local. They don’t care if dent organisations, and sometimes, just Paid But it’s no accident. Sally from Engineering decided to take sometimes, the insects that chase your 6. NTEU Strike opinions Like so many issues important to stu- a stand on the picket line, or if Damien lecturer out of their lecture hall. dents, last week’s NTEU/CPSU strike from Commerce just wanted to go to his 7. Top 5 Disney songs received wide coverage of only shallow lecture. to have sex to depth. It was exactly the kind of jour- But we do. When we campaigned and Rafi Alam nalism we railed against in the past two sought election as an editorial team the editorials; intro, quote A vs. quote B, most consistent feedback we got was Max Chalmers 9. What’s in the box? fin. The ABC, The Sydney Morning Her- that students wanted a paper that was Editor-in-chief John Gooding ald, The Daily Telegraph, and The Austra- local, a paper that was different to the lian got their Michael Thomson, Michael SMH, the Oz, the ABC. -

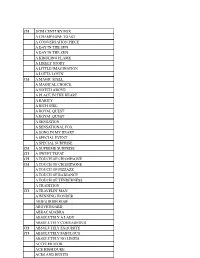

Saddlebred Sidewalk List.Docx

CH 20TH CENTURY FOX A CHAMPAGNE TOAST A CONVERSATION PIECE A DAY IN THE SUN A DAY IN THE SUN A KINDLING FLAME A LIKELY STORY A LITTLE IMAGINATION A LOTTA LOVIN' CH A MAGIC SPELL A MAGICAL CHOICE A NOTCH ABOVE A PLACE IN THE HEART A RARITY A RICH GIRL A ROYAL QUEST A ROYAL QUEST A SENSATION A SENSATIONAL FOX A SONG IN MY HEART A SPECIAL EVENT A SPECIAL SURPRISE CH A SUPREME SURPRISE CH A SWEET TREAT CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ A TOUCH OF RADIANCE A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS A TRADITION CH A TRAVELIN' MAN A WINNING WONDER ABIE'S IRISH ROSE ABOVE BOARD ABRACADABRA ABSOLUTELY A LADY ABSOLUTELY COURAGEOUS CH ABSOLUTELY EXQUISITE CH ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS ABSOLUTELY NO LIMITS ACCELERATOR ACE HIGH DUKE ACES AND EIGHTS ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS ACE HIGH DUKE ACES AND EIGHTS ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS ACE'S QUEEN ROSE ACE'S REFRESHMENT TIME ACE'S SOARING SPIRIIT ACE'S SWEET LAVENDER ACE'S TEMPTATION ACTIVE SERVICE ADF STRICTLY CLASS ADMIRAL FOX ADMIRAL'S AVENGER ADMIRAL'S BLACK FEATHER ADMIRAL'S COMMAND CH ADMIRAL'S FLEET CH ADMIRAL'S MARK CH ADMIRAL'S MARK ADMIRAL'S SHIPMATE CH ADVANTAGE ME CH ADVANTAGE ME AFFAIR OF THE HEART "JAKE" AFLAME AGLOW AGLOW AHEAD OF THE CLASS AIN'T MISBEHAVIN AIN'T MISBEHAVIN AIR OF ELEGANCE CH ALETHA STONEWALL ALEXANDER THE GREAT ALEXANDER'S EMERAUDE ALEXANDER'S EMERAUDE ALFIE ALICE LOU'S DENMARK CH ALISON MACKENZIE CH ALISON MACKENZIE CH ALL AMERICAN BOY ALL DRESSED UP ALL NIGHT LONG ALL ROSES ALL SHOW ALL THE MONEY ALLEGORY ALLIE COME LATELY "BAH" ALL'S CLEAR ALLSWEET ALLURING LADY ALONG CAME A SPIDER ALTERED IMAGE ALTON BELLE ALONG CAME A SPIDER ALTERED IMAGE ALTON BELLE CH ALVIN'S MR.