Transverse Leaf Springs: a Corvette Controversy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sp057 Leaf Spring Installation

SP057 LEAF SPRING INSTALLATION Also covering Part #RH015 1967-1969 CAMARO AND FIREBIRD NOTE: This part number is designed to use the original mounting hardware from a factory multi-leaf rear end setup. If you have a factory mono-leaf rear end or wish to upgrade the hardware for your multi-leaf setup, you can purchase the BMR leaf spring installation kit (Part #RH015). This kit includes new front mounting hardware, polyurethane leaf spring pads, larger U-bolts, and a heavy duty rear shackle kit with polyurethane frame bushings. INSTALLATION: 1. Lift vehicle and support with jack stands under the frame rails. 2. Remove the lower shock bolts. 3. Loosen the (4) nuts on the shock mounting plates then remove the plates. 4. Place a hydraulic jack under the axle. Lift the axle off the springs. 5. Loosen the nut on the rear lower shackle plates but do not remove the bolt. 6. Loosen the (3) bolts on the front leaf spring pocket and also remove the rear leaf spring bolt then remove the leaf spring from the vehicle. 7. If the vehicle was originally equipped with mono-leaf springs, knock out the factory bolts from the leaf spring axle mount (4 per side). Using a ½” drill bit, drill out the 4 holes in the leaf spring axle mounts. Also drill out the holes in the shock mounts to allow the use of ½” U-bolts. (IMAGE 1) 8. If you also purchased the leaf spring installation kit (RH015), replace the nut clips in the frame at this time. 9. If you purchased the leaf spring installation kit, knock out the upper bushings in the frame and install the supplied polyurethane bushings and inner steel sleeves. -

Suspension Geometry and Computation

Suspension Geometry and Computation By the same author: The Shock Absorber Handbook, 2nd edn (Wiley, PEP, SAE) Tires, Suspension and Handling, 2nd edn (SAE, Arnold). The High-Performance Two-Stroke Engine (Haynes) Suspension Geometry and Computation John C. Dixon, PhD, F.I.Mech.E., F.R.Ae.S. Senior Lecturer in Engineering Mechanics The Open University, Great Britain. This edition first published 2009 Ó 2009 John Wiley & Sons Ltd Registered office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. -

Adaption and Evaluation of Transversal Leaf Spring Suspension Design for a Lightweight Vehicle Using Adams /C Ar

ADAPTION AND EVALUATION OF TRANSVERSAL LEAF SPRING SUSPENSION DESIGN FOR A LIGHTWEIGHT VEHICLE USING ADAMS /C AR FLORIAN CHRIST Master Thesis in Vehicle Engineering Vehicle Dynamics Aeronautical and Vehicle Engineering Royal Institute of Technology TRITA-AVE 2015:09 ISSN 1651-7660 Adaption and Evaluation of Transversal Leaf Spring Suspension Design for a Lightweight Vehicle using Adams/Car FLORIAN CHRIST © Florian Christ, 2015. Vehicle Dynamics Department of Aeronautical and Vehicle Engineering Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan SE-100 44 Stockholm Sweden ii Abstract This investigation deals with the suspension of a lightweight medium-class vehicle for four passengers with a curb weight of 1000 kg. The suspension layout consists of a transversal leaf spring and is supported by an active air spring which is included in the damper. The lower control arms are replaced by the leaf spring ends. Active ride height control is introduced to compensate for different vehicle load states. Active steering is applied using electric linear actuators with steer-by wire design. Besides intense use of light material the inquiry should investigate whether elimination of suspension parts or a lighter component is concordant with the stability demands of the vehicle. The investigation is based on simulations obtained with MSC Software ADAMS/Car and Matlab. The suspension is modeled in Adams/Car and has to proof it's compliance in normal driving conditions and under extreme forces. Evaluation criteria are suspension kinematics and compliance such as camber, caster and toe change during wheel travel in different load states. Also the leaf spring deflection, anti-dive and anti-squat measures and brake force distribution are investigated. -

RV1 Tire Changer Manual

1645 Lemonwood Dr. Santa Paula, CA 93060 USA Toll Free: (800) 253-2363 Telephone: (805) 933-9970 rangerproducts.com Wheel Guardian™ Tire Changer Installation and Operation Manual Manual P/N 5900089 — Manual Revision A3 — November 2019 Model: • RV1 Designed and engineered in Southern California, USA. Made in China. Read the entire contents of this manual before using this product. Failure to follow the instructions and safety precautions in ⚠ DANGER this manual can result in serious injury or death. Make sure all other operators also read this manual. Keep the manual near the product for future reference. By proceeding with setup and operation, you agree that you fully understand the contents of this manual. Manual. RV1 Wheel Guardian™ Tire Changer, Installation and Operation Manual, Manual P/N 5900089, Manual Revision A3, Released November 2019. Copyright. Copyright © 2019 by BendPak Inc. All rights reserved. You may make copies of this document if you agree that: you will give full attribution to BendPak Inc., you will not make changes to the content, you do not gain any rights to this content, and you will not use the copies for commercial purposes. Trademarks. BendPak, the BendPak logo, Ranger, and the Ranger logo are registered trademarks of BendPak Inc. All other company, product, and service names are used for identification only. All trademarks and registered trademarks mentioned in this manual are the property of their respective owners. Limitations. Every effort has been made to have complete and accurate instructions in this manual. However, product updates, revisions, and/or changes may have occurred since this manual was published. -

Mini-Tub Leaf-Spring Rear Suspension for 1964-70 Mustangs

CLICK for More Info Online Mini-Tub Leaf-Spring Rear Suspension for 1964-70 Mustangs • Additional 2-3/4” tire clearance • Stronger offset frame rail inserts • Adjustable suspension geometry • Choose spring rate and ride height Mini-Tub Leaf-Spring Rear Suspension The mini-tub leaf-spring suspension from Total Control Products Applications allows substantially greater clearance for extremely large tire and wheel Mustang 64-70 combinations. Relocated shocks and springs combined with the additional mini-tub clearance allow 2-3/4” more tire clearance on each side of the vehicle. Systems include all mounts, offset frame rail inserts, leaf springs, spring plates and shock absorbers. A panhard bar version of the suspension is also offered for sharper and more predictable handling. Optional components include a narrow- width, adjustable-rate anti-roll bar and fabricated Ford 9” housing (FAB9™). Currently available for all styles of 1964-70 Mustangs. NOTE: ‘65-66 GT rear valance is not compatible with suspension. 1 Rear Spring Mounts Offset Frame Rail Insert Front Spring Mounts Relocated mount with 2-3/4” additional tire Welds inboard of OEM supporting crossmember clearance per side frame rail Panhard Bar System Upper Shock Mounts Lateral locating device Relocates stem-mount for rear end housing style shock inboard of OEM position Anti-Roll Bar FAB9 Rear End Houisng Splined arms with Fabricated Ford 9” adjustable end-link housing, structurally positions to alter rate superior to OEM 2 Mini-Tub Leaf-Spring Suspension Shown with optional Anti-Roll -

A Comparative Study of the Suspension for an Off-Road Vehicle

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 07 Issue: 05 | May 2020 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 A Comparative study of the Suspension for an Off-Road Vehicle Sivadanus.S Department of Manufacturing Engineering, College of Engineering – Guindy, Chennai ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Humans use different vehicles to travel in is set nothing can be adjusted or moved. This type of different terrains for comfort and ease of travel. An off-terrain suspension will not be considered in the scope of this project vehicle is generally used for rugged terrain and needs a largely due to its lack of adjustability. completely different dynamics in suspension comparison to an on-road vehicle. The aim of this project is to identify and Independent suspension systems provide more effective determine the parameters of vehicle dynamics with a proper functionality in traction and stability for off-roading study of suspension and to initiate a comparative study for an applications. Independent suspension systems provide flex off-road vehicle using different models. (the ability for one wheel to move vertically while still Key Words: Suspension, Vehicle Dynamics, Off-road allowing the other wheels to stay in contact with the Vehicle, Control arms, Camber surface). 1.INTRODUCTION There are many different versions and variations of independent suspensions, which include swing axle Suspension suspensions, transverse leaf spring suspensions, trailing and The role of a suspension system within a vehicle is to ensure semi-trailing suspensions, Macpherson strut suspensions, that contact between the tires and driving surface is and double wishbone suspensions. Control arms are used for continuously maintained. -

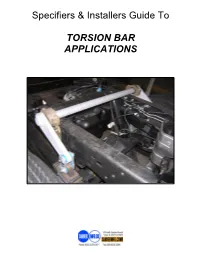

Specifiers & Installers Guide to TORSION BAR APPLICATIONS

Specifiers & Installers Guide To TORSION BAR APPLICATIONS WELCOME Thank you for specifying Sauber Torsion Bars. By choosing us as your stability partner, you derive the following benefits: * Improved Stability * Stability is safety, and safety is our first concern. A Sauber Torsion Bar can eliminate unwanted counterweight, offering your users an extra safety margin. Because Sauber bars don't rigidize the chassis frame, they always provide a smooth, quiet ride. * Long Life * Premium bronze and galvanized components. Bushings guaranteed and replaced as/if needed for 10 years. 10 Year parts coverage when inspected at no greater than four month intervals. * Excellent Documentation * Our comprehensive applications charts, installation instructions and detailed drawings provide the vital information you and your installers need in an organized format. * Superior Support * Toll-free phone and fax service from anywhere in North America provides easy access to the resources of our organization through your personal company representative. * Lower Life Cycle Costs * Since it takes less time to mount our bar, its installed cost can actually be less than other alternatives. Sauber Torsion Bars are designed and built to last as long as your chassis. * Extensive Inventory * Our inventory power puts our bar on the floor just when you want it. Your production schedule can't wait on your suppliers, and with us as your partner, it won't. * More Choices * Underframe or overframe, nobody provides more installation options than we do. More choices mean a better -

Modelling Commercial Vehicle Handling and Rolling Stability

357 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Bradford Scholars Modelling commercial vehicle handling and rolling stability K HussainÃ, W Stein, and A J Day School of Engineering, Design, and Technology, University of Bradford, Bradford, UK The manuscript was received on 3 September 2004 and was accepted after revision for publication on 28 April 2005. DOI: 10.1243/146441905X48707 Abstract: This paper presents a multi-degrees-of-freedom non-linear multibody dynamic model of a three-axle heavy commercial vehicle tractor unit, comprising a subchassis, front and rear leaf spring suspensions, steering system, and ten wheels/tyres, with a semi-trailer comprising two axles and eight wheels/tyres. The investigation is mainly concerned with the rollover stability of the articulated vehicle. The models incorporate all sources of compliance, stiffness, and damping, all with non-linear characteristics, and are constructed and simulated using automatic dynamic analysis of mechanical systems formulation. A constant radius turn test and a single lane change test (according to the ISO Standard) are simulated. The constant radius turn test shows the understeer behaviour of the vehicle, and the single lane change manoeuvre was conducted to show the transient behaviour of the vehicle. Non-stable roll and yaw behaviour of the vehicle is predicted at test speeds .90 km/h. Rollover stability of the vehicle is also investigated using a constant radius turn test with increasing speed. The articulated laden vehicle model predicted increased understeer behaviour, due to higher load acting on the wheels of the middle and rear axles of the tractor and the influence of the semi-trailer, as shown by the reduced yaw rate and the steering angle variation during the con- stant radius turn. -

Roadmaster, Experts in Dinghy Towing, Introduces the Comfort Ride Slipper Leaf Spring and Shock Absorber Systems to Road-Weary Trailer and Fifth-Wheel Owners

article and photos by Bob Livingston SUSPENSION NIRVANA Roadmaster, experts in dinghy towing, introduces the Comfort Ride Slipper Leaf Spring and Shock Absorber systems to road-weary trailer and fifth-wheel owners railers and fifth-wheels take a lot of punishment a company immersed in the tow-bar business, catering on the road. Suspensions, designed to counter this to owners towing vehicles behind their motorhomes, has Tabuse, have not changed much over the years, and expanded its offerings in the towable arena with the intro- in most cases are the same ones found on chassis that date duction of the Comfort Ride Slipper Leaf Spring Suspension back a very long time. (The old line “This isn’t your grand- and Shock Absorber systems. father’s vehicle” does not apply.) While stock suspensions The concept is simple, and the result is a game changer hold the chassis off the ground, controlling the ride is not in the way trailers and fifth-wheels handle all road conditions. a strong attribute. One might ask, “Why worry about ride quality inside Leaf springs tied to shackles and a center-mounted a trailer when towing since no one is back there to feel equalizer are supposed to counter the bumps in the road the shakes, rattles and rolls? That’s a valid question, but but, with few exceptions, are not very effective. Roadmaster, subjecting a trailer to a constant 4.0-magnitude earthquake 74 TRAILER LIFE July 2018 Roadmaster’s Comfort Ride Slipper Leaf Spring and Shock Absorber systems bolt on to the frame with only minor drilling needed to mount the center box. -

Unavoidable Friction Within Servo Motors

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Design of running-man, a bipedal robot Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/11r612s9 Author Chen, Jin Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California, San Diego Design of running-man, a bipedal robot A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Science in Engineering Sciences (Mechanical Engineering) by Jin Chen Committee in charge: Professor Tom Bewley, Chair Professor Prab Bandaru Professor Mauricio de Oliveira 2011 Copyright Jin Chen, 2011 All rights reserved. The Thesis of Jin Chen is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii To my parents and my brother, whose supports of my education are ever so generous iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ........................................................................................................iii Dedication ............................................................................................................... iv Table of Contents..................................................................................................... v List of Figures.........................................................................................................vii List of Tables............................................................................................................ix -

Design and Analysis of Leaf Spring in a Heavy Truck

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Journal of Innovative Technology and Research (IJITR) Godatha Joshua Jacob * et al. (IJITR) INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE TECHNOLOGY AND RESEARCH Volume No.5, Issue No.4, June – July 2017, 7041-7046. Design And Analysis Of Leaf Spring In A Heavy Truck GODATHA JOSHUA JACOB Mr M.DEEPAK M.Tech (machine design) Student, Dept.of Assistant professor, Dept.of Mechanical Engineering, Mechanical Engineering, Kakinada Institute Of Kakinada Institute Of Engineering And Technology, Engineering And Technology, (Approved by AICTE (Approved by AICTE and Affiliated to Jawaharlal and Affiliated to Jawaharlal Nehru Technological Nehru Technological University , Kakinada) University , Kakinada) Abstract: A leaf spring is a simple form of spring, commonly used for the suspension in wheeled vehicles. Leaf Springs are long and narrow plates attached to the frame of a trailer that rest above or below the trailer's axle. There are monoleaf springs, or single-leaf springs, that consist of simply one plate of spring steel. These are usually thick in the middle and taper out toward the end, and they don't typically offer too much strength and suspension for towed vehicles. Drivers looking to tow heavier loads typically use multileaf springs, which consist of several leaf springs of varying length stacked on top of each other. The shorter the leaf spring, the closer to the bottom it will be, giving it the same semielliptical shape a single leaf spring gets from being thicker in the middle. Springs will fail from fatigue caused by the repeated flexing of the spring. -

Numerical and Experimental Analysis of Torsion Springs Using NURBS Curves

applied sciences Article Numerical and Experimental Analysis of Torsion Springs Using NURBS Curves Young Shin Kim 1, Yu Jun Song 2 and Euy Sik Jeon 3,* 1 Industrial Technology Research Institute, Kongju National University, Cheonan-daero, Seobuk-gu, Cheonan-si 31080, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea; [email protected] 2 International Testing and Evaluation Laboratory (ITEL), 53, Osongsaengmyeong 10-ro, Osong-eup, heungdeok-gu, Cheongju-si 28164, Chungcheongbuk-do, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Graduate School, Kongju National University, Cheonan-daero, Seobuk-gu, Cheonan-si 31080, Chungcheongnam-do, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-41-521-9284 Received: 28 March 2020; Accepted: 7 April 2020; Published: 10 April 2020 Abstract: Torsion springs, which transfer power through the twisting of their coil, provide advantages such as module simplification and efficient use of space. The design of a torsion spring has been formulated, but it is difficult to determine the local behaviors of torsion springs according to actual load conditions. This study proposes a torsion-spring design method through finite element analysis (FEA) using nonuniform-rational-basis-spline (NURBS) curves. Through experimentation, the angle and displacement values for the actual spring load were converted into useable data. Torsion-spring displacement values were obtained via experimentation and converted into coordinates that may be expressed using NURBS curves. The results of these experiments were then compared to those obtained via FEA, and the validity of this method was thereby verified. Keywords: torsion springs; FEA; NURBS; applied load; local behaviors 1. Introduction Torsion springs transfer power through the twisting of their coil, and provide advantages such as module simplification, efficient use of space, and reduction of overall product weight.