Art-Sanat, 14(2020): 185–209

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

171 Abdülkerimzade Mehmed, 171 Abdullah Bin Mercan, 171

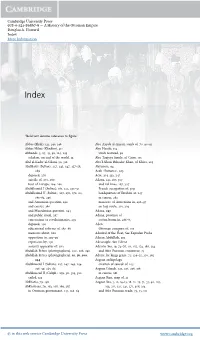

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17716-1 — Scholars and Sultans in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire Abdurrahman Atçıl Index More Information Index Abdülkerim (Vizeli), 171 AliFenari(FenariAlisi),66 Abdülkerimzade Mehmed, 171 ʿAli bin Abi Talib (fourth caliph), 88 Abdullah bin Mercan, 171 Ali Ku¸sçu, 65, 66, 77n77 Abdülvahhab bin Abdülkerim, 101 Al-Malik al-Muʾayyad (Mamluk ruler), Abdurrahman bin Seydi Ali, 157, 42 157n40 Altıncızade (Mehmed II’s physician), Abdurrahman Cami, 64 80 Abu Bakr (irst caliph), 94 Amasya, 127n37, 177 Abu Hanifa, 11 joint teaching and jurist position in, ahi organization, 22 197 Ahizade Yusuf, 100 judgeship of, 79n84 Ahmed, Prince (Bayezid II’s son), 86, Anatolian principalities, 1, 20, 21, 22, 87 23n22, 24n26, 25, 26, 28, 36, 44, Ahmed Bey Madrasa, 159 64 Ahmed Bican (Sui writer), 56 Ankara, 25, 115, 178 Ahmed Pasha (governor of Egypt), 123 battle of, 25, 54 Ahmed Pasha bin Hızır Bey. See Müfti joint teaching and jurist position in, Ahmed Pasha 197 Ahmed Pasha bin Veliyyüddin, 80 Arab Hekim (Mehmed II’s physician), Ahmed Pasha Madrasa (Alasonya), 80 161 Arab lands, 19, 36, 42, 50, 106, Ahmedi (poet), 34 110n83, 119, 142, 201, 202, ʿAʾisha (Prophet’s wife), 94 221 Akkoyunlus, 65, 66 A¸sık Çelebi, 10 Ak¸semseddin, 51, 61 A¸sıkpa¸sazade, 38, 67, 91 Alaeddin Ali bin Yusuf Fenari, 70n43, Ataullah Acemi, 66, 80 76 Atayi, Nevizade, 11, 140, 140n21, Alaeddin Esved, 33, 39 140n22, 194, 200 Alaeddin Pasha (Osman’s vizier), 40 Hadaʾiq al-Haqaʾiq, 11, 206 Alaeddin Tusi, 42, 60n5, 68n39, 81 Ayasofya Madrasa, 60, 65, 71, -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Islahi, Abdul Azim Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 06 Dec 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. There is a need to explore Muslim economic ideas in works written in Persian, Turkish and other languages, as the importance of these languages increased in later periods. -

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan

Christian Allies of the Ottoman Empire by Emrah Safa Gürkan The relationship between the Ottomans and the Christians did not evolve around continuous hostility and conflict, as is generally assumed. The Ottomans employed Christians extensively, used Western know-how and technology, and en- couraged European merchants to trade in the Levant. On the state level, too, what dictated international diplomacy was not the religious factors, but rather rational strategies that were the results of carefully calculated priorities, for in- stance, several alliances between the Ottomans and the Christian states. All this cooperation blurred the cultural bound- aries and facilitated the flow of people, ideas, technologies and goods from one civilization to another. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Christians in the Service of the Ottomans 3. Ottoman Alliances with the Christian States 4. Conclusion 5. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation Introduction Cooperation between the Ottomans and various Christian groups and individuals started as early as the beginning of the 14th century, when the Ottoman state itself emerged. The Ottomans, although a Muslim polity, did not hesitate to cooperate with Christians for practical reasons. Nevertheless, the misreading of the Ghaza (Holy War) literature1 and the consequent romanticization of the Ottomans' struggle in carrying the banner of Islam conceal the true nature of rela- tions between Muslims and Christians. Rather than an inevitable conflict, what prevailed was cooperation in which cul- tural, ethnic, and religious boundaries seemed to disappear. Ÿ1 The Ottomans came into contact and allied themselves with Christians on two levels. Firstly, Christian allies of the Ot- tomans were individuals; the Ottomans employed a number of Christians in their service, mostly, but not always, after they had converted. -

The Architectural Projects of the Grandees of Mehmed Ii

APPENDIX III THE ARCHITECTURAL PROJECTS OF THE GRANDEES OF MEHMED II In this Appendix there will be an attempt to examine the architectural projects of selected high officials who were Mahmud Pasha's contem poraries. These will be Zaganos Pasha, ishak Pasha, Rum Mehmed Pasha, Gedik Ahmed Pasha, Hass Murad Pasha and Karamani Meh med Pasha. All ofthese men became Grand Vezirs with the exception of Hass Murad Pasha, who died at a young age as Beylerbeyi of Rumeli. Four of them, Zaganos Pasha, Rum Mehmed Pasha, Gedik Ahmed Pasha and Hass Murad Pasha, were converts, while ishak Pasha and Karamani Mehmed Pasha were not. Zaganos Pasha I Zaganos Pasha's main architectural project was in Bahkesir, in Anato lia, where he spent time after his two exiles, upon Murad II's return to the throne in 1446 and upon his fall from grace in the reign of Mehmed II, probably in 1456.2 If we combine this information with the fact that Zaganos Pasha appears to have died in Bahkesir in AH 865 (1460-1461), where he was also buried, we may reach the conclu sion that he must have had his hass in that town. In Bahkesir Zaganos Pasha built a complex, which included a mosque, a soup kitchen and public baths.' as well as the founder's tomb, which bears the date AH 865 (1460-1461).4 The posthumous endowment deed for this complex is dated AH 866 (1461-1462). 5 He also constructed several buildings in Rumeli. An important contribution of Zaganos Pasha to Ottoman military architecture was his building of a part of Rumeli I For information on Zaganos Pasha see Chapter I. -

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — a History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89867-6 — A History of the Ottoman Empire Douglas A. Howard Index More Information Index “Bold text denotes reference to figure” Abbas (Shah), 121, 140, 148 Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, tomb of, 70, 90–91 Abbas Hilmi (Khedive), 311 Abu Hanifa, 114 Abbasids, 3, 27, 45, 92, 124, 149 tomb restored, 92 scholars, on end of the world, 53 Abu Taqiyya family, of Cairo, 155 Abd al-Kader al-Gilani, 92, 316 Abu’l-Ghazi Bahadur Khan, of Khiva, 265 Abdülaziz (Sultan), 227, 245, 247, 257–58, Abyssinia, 94 289 Aceh (Sumatra), 203 deposed, 270 Acre, 214, 233, 247 suicide of, 270, 280 Adana, 141, 287, 307 tour of Europe, 264, 266 and rail lines, 287, 307 Abdülhamid I (Sultan), 181, 222, 230–31 French occupation of, 309 Abdülhamid II (Sultan), 227, 270, 278–80, headquarters of Ibrahim at, 247 283–84, 296 in census, 282 and Armenian question, 292 massacre of Armenians in, 296–97 and census, 280 on hajj route, 201, 203 and Macedonian question, 294 Adana, 297 and public ritual, 287 Adana, province of concessions to revolutionaries, 295 cotton boom in, 286–87 deposed, 296 Aden educational reforms of, 287–88 Ottoman conquest of, 105 memoirs about, 280 Admiral of the Fleet, See Kapudan Pasha opposition to, 292–93 Adnan Abdülhak, 319 repression by, 292 Adrianople. See Edirne security apparatus of, 280 Adriatic Sea, 19, 74–76, 111, 155, 174, 186, 234 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 200, 288, 290 and Afro-Eurasian commerce, 74 Abdullah Frères (photographers), 10, 56, 200, Advice for kings genre, 71, 124–25, 150, 262 244 Aegean archipelago -

3 Introducing the Ottoman Empire 49 4 Scholars in Mehmed II’S Nascent Imperial Bureaucracy (1453–1481) 59 5 Scholar-Bureaucrats Realize Their Power (1481–1530) 83

Scholars and Sultans in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire During the early Ottoman period (1300–1453), scholars in the empire carefully kept their distance from the ruling class. This changed with the capture of Constantinople. From 1453 to 1600, the Ottoman government coopted large groups of scholars, usually more than a thousand at a time, and employed them in a hierarchical bureaucracy to fulfill educational, legal, and administrative tasks. Abdurrahman Atçıl explores the factors that brought about this gradual transformation of scholars into scholar- bureaucrats, including the deliberate legal, bureaucratic, and architectural actions of the Ottoman sultans and their representatives, scholars’ own participation in shaping the rules governing their status and careers, and domestic and international events beyond the control of either group. abdurrahman atçıl is Assistant Professor and a fellow of the Brain Circulation Scheme, co-funded by the European Research Council and the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey, at IstanbulSehir ¸ University. He also holds an assistant professorship in Arabic and Islamic studies at Queens College, City University of New York. Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Cambridge University Library, on 13 Feb 2017 at 10:56:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316819326 Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. Cambridge University Library, on 13 Feb 2017 at 10:56:57, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https:/www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316819326 Scholars and Sultans in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire abdurrahman atçıl Downloaded from https:/www.cambridge.org/core. -

British Embassy Reports on the Greek Uprising in 1821-1822: War of Independence Or War of Religion?

University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons History Faculty Publications Department of History 2011 British Embassy Reports on the Greek Uprising in 1821-1822: War of Independence or War of Religion? Theophilus C. Prousis University of North Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub Part of the Diplomatic History Commons Recommended Citation Prousis, Theophilus C., "British Embassy Reports on the Greek Uprising in 1821-1822: War of Independence or War of Religion?" (2011). History Faculty Publications. 21. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ahis_facpub/21 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2011 All Rights Reserved “BRITISH EMBASSY REPORTS ON THE GREEK UPRISING IN 1821-1822: WAR OF INDEPENDENCE OR WAR OF RELIGION?” THEOPHILUS C. PROUSIS* In a dispatch of 10 April 1821 to Foreign Secretary Castlereagh, Britain’s ambassador to the Sublime Porte (Lord Strangford) evoked the prevalence of religious mentalities and religiously induced reprisals in the initial phase of the Greek War of Independence. The sultan’s “government perseveres in its endeavours to strike terror into the minds of its Greek subjects; and it seems that these efforts have been very successful. The commerce of the Greeks has been altogether suspended – their houses -

A Study of Muslim Economic Thinking in the 11Th A.H. / 17Th C.E. Century

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Munich Personal RePEc Archive MPRA Munich Personal RePEc Archive A study of Muslim economic thinking in the 11th A.H. / 17th C.E. century Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Institute, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, KSA 2009 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/75431/ MPRA Paper No. 75431, posted 6 December 2016 02:55 UTC Abdul Azim Islahi Islamic Economics Research Center King Abdulaziz University Scientific Publising Centre King Abdulaziz University P.O. Box 80200, Jeddah, 21589 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia FOREWORD There are numerous works on the history of Islamic economic thought. But almost all researches come to an end in 9th AH/15th CE century. We hardly find a reference to the economic ideas of Muslim scholars who lived in the 16th or 17th century, in works dealing with the history of Islamic economic thought. The period after the 9th/15th century remained largely unexplored. Dr. Islahi has ventured to investigate the periods after the 9th/15th century. He has already completed a study on Muslim economic thinking and institutions in the 10th/16th century (2009). In the mean time, he carried out the study on Muslim economic thinking during the 11th/17th century, which is now in your hand. As the author would like to note, it is only a sketch of the economic ideas in the period under study and a research initiative. It covers the sources available in Arabic, with a focus on the heartland of Islam. -

Architecture and Landscape in Medieval Anatolia, 1100−1500

Architecture and Landscape in Medieval Anatolia, 1100−1500 Edited by Patricia Blessing and Rachel Goshgarian ARCHITECTURE AND LANDSCAPE IN MEDIEVAL ANATOLIA, 1100–1500 Edited by Patricia Blessing and Rachel Goshgarian Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation Patricia Blessing and Rachel Goshgarian, 2017 © the chapters their several authors, 2017 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12 (2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 10/12 pt Trump Medieval by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 1129 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 1130 1 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 1131 8 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identifed as authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). Published with the support of the University of Edinburgh Scholarly Publishing Initiatives Fund. CHAPTER NINE All Quiet on the Eastern Frontier? The Contemporaries of Early Ottoman Architecture in Eastern Anatolia Patricia Blessing Anatolian monuments built under the successor dynasties of the Ilkhanids in the mid-fourteenth to the mid-fifteenth century were close contemporaries to their early Ottoman counterparts. -

Mohammad Ali Pasha and His Contribution to the Modernisation of Egypt

MOHAMMAD ALI PASHA AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE MODERNISATION OF EGYPT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ©octor of ipijilosfoplip IN ISLAMIC STUDIES By FARHEEN AZRA UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. ADAM MALIK KHAN DEPARTMENT OF ISLAMIC STUDIES ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2012 I \ OCT 2014 T8825 (1769-1849) CONTENTS Page No. Acknowledgement i-ii Introduction 1-7 Chapter First: French Occupation of Egypt 8-41 Battle of Cairo 22 Battle of Pyramids 22 Battle of Nile 23 Proclamation of War 3 3 Chapter Second: Mohammad Ali Pasha as a Turkish Military 42-70 Officer Chapter Third: Political and Administrative Reforms of 71-113 Mohammad Ali Pasha New Structure of Administration 72 Principal Units of Central Administration under Mohammad Ali 77 1837 Muhammad All's New Ruling Class 79 Chapter Fourth: Economic and Educational Reforms of 114-150 Mohammad Ali Pasha Effects of Muhammad Ali's Economic Reforms 124 Educational Reforms 128 Establishment of Schools and Colleges 132 Conclusion 151-157 Bibliography 158-171 Acknowledgment Jidthe (Praises andtfian^ to jUXJiyf, JiCmigfity Creator andSustainer of the worQf, M^Ho made itpossiSkforme to accompCish the research wor^ I than^my Lord for giving me nice parents whose (ove, sacrifices and sustained efforts enaSCed me to acquire ^owledge. Whatever I am today is Because of their prayers, Coving care and service endeavors. (During this research wor^ I have faced many proSCems, But ^od is great. So, I have received heCp from various quarters that I want to ac^nowCedge from the core of my heart. My speciaCthan^ to my supervisor (Dr. -

The Sokollu Family Clan and the Politics of Vizierial

Uroš Dakiü THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY MA Thesis in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2012 THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Uroš Dakiü (Serbia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2012 ii THE SOKOLLU FAMILY CLAN AND THE POLITICS OF VIZIERIAL HOUSEHOLDS IN THE SECOND HALF OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by Uroš Dakiü (Serbia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with the specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2012 iii THE SOKOLLU -

GAZİANTEP UNIVERSITY FACULTY of ARCHITECTURE

GAZİANTEP UNIVERSITY FACULTY of ARCHITECTURE 2018-19 Fall Semester Name of the course: Architectural History II Course code: ARCH 211 Name of the Module: Ottoman Architecture in Istanbul ECTS Credit: 4 2nd year– 1st term Undergraduate Compulsory 3 h/w Theoretical: 3 hours per week Practical: 0 h/w Course language: English Instructor: Asst. Prof. Muzaffer Özgüleş Address: Gaziantep University, Faculty of Architecture, Office: 207 e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +90 342 317 2666 Office Hour: Wednesday 14:00-15:00 Course web page: http://www.gantep.edu.tr/ab/ders_icerik.php?id=6867&bolum_id=20255733 DESCRIPTION OF THE COURSE This course module, entitled “Ottoman Architecture in Istanbul”, is designed as a part of ARCH211 Architectural History course taught at Gaziantep University’s Faculty of Architecture for the second year undergraduate students. It is composed of four lectures, each having two parts, and it is adjusted for four weeks of the semester. The contents of the course module will be taught via Timeline Travel e- learning platform. OBJECTIVE OF THE COURSE The primary objective of the course is initiating the encounter of the students with the examples and notion of Ottoman architecture, through the lens of significant historic buildings located in Istanbul, as well as some others in Bursa and Edirne. General objectives The general objectives of the course are as follows: - Learning Ottoman architecture and its principal characteristics. - Understanding different features of Ottoman architecture in different periods. - Differentiating the characteristics of Ottoman architecture from other architectural styles. - Understanding the development of Ottoman Istanbul in the course of history.