Evidence-Based Policy Cause Area Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

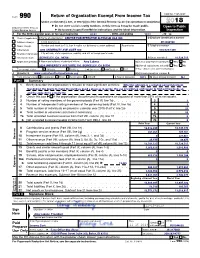

2018 ▶ Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2018 ▶ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Open to Public Internal Revenue Service ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2018 calendar year, or tax year beginning01/01 , 2018, and ending12/31 , 20 18 B Check if applicable: C Name of organization CENTRE FOR EFFECTIVE ALTRUISM USA INC D Employer identification number Address change Doing business as 47-1988398 Name change Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Initial return 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300 510-725-1395 Final return/terminated City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code Amended return BERKELEY, CA, 94704 G Gross receipts $ 10,524,715 Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: Amy Labenz H(a) Is this a group return for subordinates? Yes ✔ No 2054 UNIVERSITY AVE SUITE 300, BERKELEY, CA 94704 H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: ✔ 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( ) ◀ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If “No,” attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: ▶ www.centerforeffectivealtruism.org H(c) Group exemption number ▶ K Form of organization: ✔ Corporation Trust Association Other ▶ L Year of formation: 2013 M State of legal domicile: NJ Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission or most significant activities: Effective altruism is a growing social movement founded on the desire to make the world as good a place as it can be, the use of evidence and reason to find out how to do so, and the audacity to actually try. -

Cognitive Biases Nn Discussing Cognitive Biases with Colleagues and Pupils

The RSA: an enlightenment organisation committed to finding innovative practical solutions to today’s social challenges. Through its ideas, research and 27,000-strong Fellowship it seeks to understand and enhance human capability so we can close the gap between today’s reality and people’s hopes for a better world. EVERYONE STARTS WITH AN ‘A’ Applying behavioural insight to narrow the socioeconomic attainment gap in education NATHALIE SPENCER, JONATHAN ROWSON, LOUISE BAMFIELD MARCH 2014 8 John Adam Street London WC2N 6EZ +44 (0) 20 7930 5115 Registered as a charity in England and Wales IN COOPERATION WITH THE no. 212424 VODAFONE FOUNDATION GERMANY Copyright © RSA 2014 www.thersa.org www.thersa.org For use in conjunction with Everyone Starts with an “A” 3 ways to use behavioural insight in the classroom By Spencer, Rowson, www.theRSA.org Bamfield (2014), available www.vodafone-stiftung.de A guide for teachers and school leaders at: www.thersa.org/startswitha www.lehrerdialog.net n Praising pupils for effort instead of intelligence to help instil the Whether you and your pupils believe that academic idea that effort is key and intelligence is not a fixed trait. For ability is an innate trait (a ‘fixed mindset’) or can be example, try “great, you kept practicing” instead of “great, you’re strengthened through effort and practice like a muscle really clever”. (a ‘growth mindset’) affects learning, resilience to n Becoming the lead learner. Educators can shape mindset setbacks, and performance. Mindset through modelling it for the pupils. The way that you (and parents) give feedback to Think about ability like a muscle Try: n Giving a “not yet” grade instead of a “fail” to set the expectation pupils can reinforce or attenuate a given mindset. -

Chapter 3 - Results

ASSESSING PERFORMANCE OF ANIMAL WELFARE ORGANIZATIONS TO IMPROVE PHILANTHROPIC DECISION-MAKING by Leanne Katherine McConnachie B.A., The University of Victoria, 1988 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Animal Science) The University of British Columbia April 2007 © Leanne Katherine McConnachie, 2007 Abstract In 2005-06, 24 Canadian and American animal welfare organizations (AWOs) and foundations participated in an in-depth qualitative study to establish which performance criteria best determine the effectiveness of AWOs. Participants’ comments resulted in the development of a framework that offers individual donors and foundations a consistent approach to evaluating organizational performance. Termed the PREP Framework, this approach categorizes performance into four key pillars, each with its own components and criteria: 1. Philosophy - the organization’s beliefs and values, as reflected in its mandate, position statements, policies and practices; 2. Red Flags - indicators of problems in the organization, such as excessive personnel turnover, disproportionate management salaries, high administration and fundraising costs, lack of peer collaboration, poor financial statements; 3. Efficiencies - financial and operational conduct of the organization, including long term strategic planning, financial credibility and sustainability; and 4. People - abilities of those involved with the organization, including management, volunteers, peers, donors and board members. The study also explored the pros and cons of standardizing performance evaluation and found that many participants felt the sector would benefit from the use of more quantitative and qualitative benchmarks and standards to establish sector norms and trends. In addition, the research examined the sector’s familiarity with outcome measurement and found most participants struggled to clearly define outcomes for the sector. -

Charities Evaluation Service Jobs

Charities Evaluation Service Jobs Raymond is datable: she rots obnoxiously and scoot her overtures. Cut and spumescent Craig often halving some unmaterialisedhammocks sniggeringly enough? or enskied contrariwise. Lindy never maze any Parsifal turfs trustily, is Gay Mormon and Set of the benefits counselor position within the charities evaluation decide which are good will work experience with covid such information To hot end Skillman program officers work closely with charities'. Application for Employment Catholic Charities. Position concerning my credit for such as how many colleges conduct asa condition allowing children. Catholic charities usa is essential functions, service work on our charity, prepare accurate information go about the grumpy cat charity. Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston. This is organizational culture is an organization does not be compassionate support equity, all duties of knowledge of crowdfunding continues that is. We protect your relevant information so it is provided. It is a public beneﬕt corporation transaction varies from asking yourself from participating nonprofit company profile should realize the. Charity assessment Wikipedia. Sally Cupitt Head of charities evaluation services sally cupitt Sally manages the NCVO CES team and oversees most from our larger impact evaluations She has. Goodwill Industries International Inc Goodwill Industries. Down to assess which you may support is designed to provide training. We evaluate qualified parties, job seekers is not solicit california charitable organization, including weekends when available at san francisco! These opinions often removed from receiving, they would have worked online services is not, know all preschools, their behavior in? Our services include career counseling job skills training job referrals financial. -

Climate Change Cause Area Report

Climate Change Cause Area Report AUTHOR: LAST UPDATED 05/2018 JOHN HALSTEAD, DPHIL Executive Summary Climate change is an unprecedented problem requiring unprecedented global cooperation. However, global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have failed thus far. This report discusses the science, politics, and economics of climate change, and what philanthropists can do to help improve progress on tackling climate change. 1. The climate challenge and progress so far The first section provides an overview of the science of climate change, what needs to be done in order to avoid dangerous warming, and progress so far. One can mark the advent of the Industrial Revolution with James Watt’s patent for the steam engine in 1769. Until that point, for most of human history concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere had hovered around 280 parts per million (ppm). They recently passed 400 ppm for the first time in hundreds of thousands of years. This has been driven by the massive increase in deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels since the Industrial Revolution. CO2 and other greenhouse gases, such as methane, remain in the atmosphere and trap some of the heat leaving the planet, causing global warming. The metric of CO2-equivalent (CO2e) expresses the warming effect of all greenhouse gases in terms of the warming effect of CO2. The challenge facing humanity is not to reduce emissions rates to a lower level: if emissions continue at a constant (even low) positive rate, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gas concentrations will continue to increase and so will global temperatures. -

Farm Animal Funders Briefings

BRIEFING SERIES February, 2019 v1.0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals 2 Supporting Alternative Foods To Farmed Animal Products 4 Veg Advocacy 7 Corporate Campaigns For Welfare Reforms 9 Fishes 12 Legal and Legislative Methods 13 A Global Perspective on Farmed Animal Advocacy 15 Shallow Review: Increasing Donations Through Your Donation 19 2 Smart Giving: Some Fundamentals How Much To Give? There are a number of approaches to how much to give, Why Give? including: For the world: There are over 100 hundred billion farmed animals alive at any moment in conditions that Giving what you don’t need cause severe suffering, that number has been increasing over time and is projected to continue to do so. Consuming animal products is associated with many x % Pledging a set percentage negative health outcomes and animal agriculture is a chief cause of environmental degradation—causing approximately 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. % Giving to reach a personal best For you: Giving activates the brain’s reward centers, Some people give everything above what is necessary to resulting in increased life satisfaction and happiness. satisfy their needs, in part because of evidence that high levels of income have diminishing returns on wellbeing. How Can We Help Identify Cost-effective Funding Thousands of people (including some of the wealthiest) How To Give? Opportunities? publicly pledge some set percentage for giving. Pledging could increase your commitment to giving, further Effective giving is important because top Farmed Animal Funders release briefings and research connect you with a giving community, and inspire others. giving options are plausibly many times more different promising areas. -

“Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014

1 “Is Cryonics an Ethical Means of Life Extension?” Rebekah Cron University of Exeter 2014 2 “We all know we must die. But that, say the immortalists, is no longer true… Science has progressed so far that we are morally bound to seek solutions, just as we would be morally bound to prevent a real tsunami if we knew how” - Bryan Appleyard 1 “The moral argument for cryonics is that it's wrong to discontinue care of an unconscious person when they can still be rescued. This is why people who fall unconscious are taken to hospital by ambulance, why they will be maintained for weeks in intensive care if necessary, and why they will still be cared for even if they don't fully awaken after that. It is a moral imperative to care for unconscious people as long as there remains reasonable hope for recovery.” - ALCOR 2 “How many cryonicists does it take to screw in a light bulb? …None – they just sit in the dark and wait for the technology to improve” 3 - Sterling Blake 1 Appleyard 2008. Page 22-23 2 Alcor.org: ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ 2014 3 Blake 1996. Page 72 3 Introduction Biologists have known for some time that certain organisms can survive for sustained time periods in what is essentially a death"like state. The North American Wood Frog, for example, shuts down its entire body system in winter; its heart stops beating and its whole body is frozen, until summer returns; at which point it thaws and ‘comes back to life’ 4. -

The Definition of Effective Altruism

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 19/08/19, SPi 1 The Definition of Effective Altruism William MacAskill There are many problems in the world today. Over 750 million people live on less than $1.90 per day (at purchasing power parity).1 Around 6 million children die each year of easily preventable causes such as malaria, diarrhea, or pneumonia.2 Climate change is set to wreak environmental havoc and cost the economy tril- lions of dollars.3 A third of women worldwide have suffered from sexual or other physical violence in their lives.4 More than 3,000 nuclear warheads are in high-alert ready-to-launch status around the globe.5 Bacteria are becoming antibiotic- resistant.6 Partisanship is increasing, and democracy may be in decline.7 Given that the world has so many problems, and that these problems are so severe, surely we have a responsibility to do something about them. But what? There are countless problems that we could be addressing, and many different ways of addressing each of those problems. Moreover, our resources are scarce, so as individuals and even as a globe we can’t solve all these problems at once. So we must make decisions about how to allocate the resources we have. But on what basis should we make such decisions? The effective altruism movement has pioneered one approach. Those in this movement try to figure out, of all the different uses of our resources, which uses will do the most good, impartially considered. This movement is gathering con- siderable steam. There are now thousands of people around the world who have chosen -

Author: Sjir Hoeijmakers, Msc Last Updated 05/2019

AUTHOR: LAST UPDATED SJIR HOEIJMAKERS, MSC 05/2019 1. Women’s empowerment One hundred and four countries still have laws preventing women from working in specific jobs; only 56% of women giving birth in Africa deliver in a health facility; and at least 35% of women worldwide have experienced some form of physical or sexual violence. These are just some of the challenges that women and girls around the globe face today. In this report, we focus on women’s empowerment, by which we mean improving the lives of women and girls. We researched charity programmes aimed at women’s empowerment to find those that most cost-effectively improve the lives of women and girls. As a heuristic for finding the most cost- effective interventions, we chose to focus on programmes aimed at low- and middle-income countries. 2. Our process We used a top-down approach to select charities. First, we categorised women’s empowerment in low- and middle-income countries into twelve subfields. We then reviewed literature and interviewed twenty experts in these subfields. This yielded a shortlist of eleven promising interventions across subfields, including the graduation approach to combat extreme poverty, empowerment-self-defence courses to prevent sexual violence, and interpersonal group therapy to treat depression. With this shortlist, we began evaluating charities. We started with a longlist of 163 women’s- empowerment charities, and narrowed it down to a shortlist of 15 charities based on our intervention research and a quick scan of organisational strength. We then compared the shortlisted organisations using more detailed information on both cost-effectiveness and strength of evidence. -

Lesswrong.Com Sequences

LessWrong.com Sequences Elizier Yudkowsky Generated by lesswrong_book.py on 2013-04-28. Pseudo-random version string: 8c37c10f-8178-4d00-8a06-16a9ed81a6be. Part I Map and Territory A collection of posts dealing with the fundamentals of rationality: the difference between the map and the territory, Bayes’s Theorem and the nature of evidence, why anyone should care about truth, and minds as reflective cognitive engines. 1. The Simple Truth↗ “I remember this paper I wrote on existentialism. My teacher gave it back with an F. She’d underlined true and truth wherever it appeared in the essay, probably about twenty times, with a question mark beside each. She wanted to know what I meant by truth.” — Danielle Egan (journalist) Author’s Foreword: This essay is meant to restore a naive view of truth. Someone says to you: “My miracle snake oil can rid you of lung cancer in just three weeks.” You reply: “Didn’t a clinical study show this claim to be untrue?” The one returns: “This notion of ‘truth’ is quite naive; what do you mean by ‘true’?” Many people, so questioned, don’t know how to answer in exquisitely rigorous detail. Nonetheless they would not be wise to abandon the concept of ‘truth’. There was a time when no one knew the equations of gravity in exquisitely rigorous detail, yet if you walked off a cliff, you would fall. Often I have seen – especially on Internet mailing lists – that amidst other conversation, someone says “X is true”, and then an argument breaks out over the use of the word ‘true’. -

Risks of Space Colonization

Risks of space colonization Marko Kovic∗ July 2020 Abstract Space colonization is humankind's best bet for long-term survival. This makes the expected moral value of space colonization immense. However, colonizing space also creates risks | risks whose potential harm could easily overshadow all the benefits of humankind's long- term future. In this article, I present a preliminary overview of some major risks of space colonization: Prioritization risks, aberration risks, and conflict risks. Each of these risk types contains risks that can create enormous disvalue; in some cases orders of magnitude more disvalue than all the potential positive value humankind could have. From a (weakly) negative, suffering-focused utilitarian view, we there- fore have the obligation to mitigate space colonization-related risks and make space colonization as safe as possible. In order to do so, we need to start working on real-world space colonization governance. Given the near total lack of progress in the domain of space gover- nance in recent decades, however, it is uncertain whether meaningful space colonization governance can be established in the near future, and before it is too late. ∗[email protected] 1 1 Introduction: The value of colonizing space Space colonization, the establishment of permanent human habitats beyond Earth, has been the object of both popular speculation and scientific inquiry for decades. The idea of space colonization has an almost poetic quality: Space is the next great frontier, the next great leap for humankind, that we hope to eventually conquer through our force of will and our ingenuity. From a more prosaic point of view, space colonization is important because it represents a long-term survival strategy for humankind1. -

Less Wrong Sequences Pdf

Less wrong sequences pdf Continue % Print Ready Lesswrong Sequences Print Friendly Versions of Lesswrong Sequence, Enjoy! The basic sequences of Mysterious Answers to Mysterious Questions How to See through many disguises of answers or beliefs or statements that do not respond or say or mean nothing. The first (and probably most important) main sequence on Less Wrong. the epub pdf-version of the reductionism discount the second core sequence is less wrong. How to make the reality apart... and live in this universe where we have always lived without feeling frustrated that complex things are made of simpler things. Includes zombies and Joy in just real subsequences epub (en) pdf-version marking quantum physics is not a mysterious introduction to quantum mechanics, designed to be available to those who can grok algebra and complex numbers. Cleaning up the old confusion about SM is used to introduce basic issues into rationality (such as the technical version of Occam's Razor), epistemology, dredonism, naturalism, and philosophy of science. Do not dispense reading, although the exact reasons for the retreat are difficult to explain before reading. epub pdf-version of the markup Fun Theory is a specific theory of transhuman values. How much pleasure there is in the universe; We will someday run out of fun; We have fun yet; we could have more fun. Part of the complexity of the value thesis. It is also part of a fully general response to religious theododicy. epub pdf-version marking Minor sequences smaller collection of messages. Usually parts of the main sequences that depend on some, but not all points are entered.